Every generation of filmmaker seems to want to make their mark on the horror genre. Since the German Expressionists revolutionized the use of contrasting shadows and light in films like Nosferatu (1922) and off-kilter production design like those in The Cabinet of Dr. Kaligari (1926) as a means of conveying terror in the audience, horror has been a dominant genre in the medium. Universal Pictures popularized the genre with their monster features in the 30’s and 40’s, and the post-war era gave way to the B-picture brand of kitsch horror. Then came the slasher films, which took advantage of the end of the Hollywood Production code in order to increase the level of gore on screen. Though the styles have changed, the genre has managed to remain resilient through the years, and that’s mainly because of it’s exceptional ability to adapt to the changing times and values, more than any other genre. I think that it’s mostly because the Horror genre targets a younger audience; albeit an audience on the cusp of adulthood. Because Horror movies are targeted at a young adult audience, they are intended to be more in tune with what younger people value; though it doesn’t always work that way. That’s why you always see clearly defined lines between different eras in the Horror genre; because every era’s audience is different. Usually you’ll find a defining film that helped to guide each era’s character in the Horror genre; whether it was Friday the 13th (1980) for the slasher 80’s or Scream (1996) for the self aware 90’s. But, if there was ever a horror film that had the unlikeliest legacy, it would be the unexpected hit, The Blair Witch Project (1999).

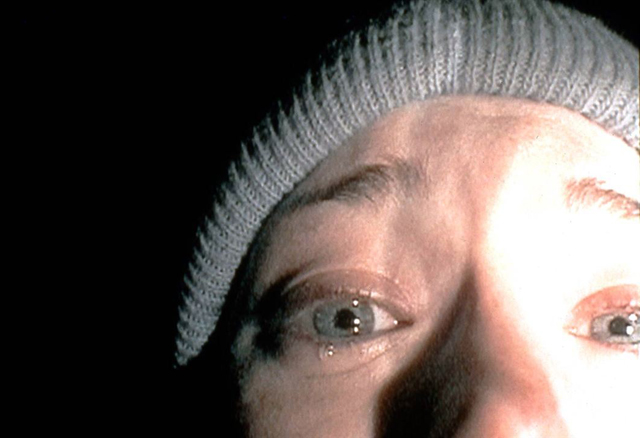

The Blair Witch Project was the horror movie blockbuster that no one saw coming. Made on a shoestring budget, Blair Witch brought a new concept to the genre, and that was the use of “found footage.” The film proposed that it was pieced together from real footage shot by student filmmakers on the search for a fabled witch who had been haunting the woods around a small Maryland town for centuries. With their gear in tow, the three documentarians set out to find out if the local legends are true, and the deeper they travel, the weirder things get. Their cameras pick up strange phenomena and eventually they start to become harassed by someone or something out in the wilderness. Madness and frustration begins to take hold of the filmmakers and they begin to suspect each other. When one of them goes missing, then it turns into a life or death situation for the remaining duo. And soon, they learn that there is indeed no way out for them and all they can do is to continue to record their experience in the hope that their story may be told. Of course, none of the footage is found at all. The three filmmakers are really just actors following a script (Joshua Leonard, Michael C. Williams and Heather Donahue respectively) and the legendary “Blair Witch” was a complete fabrication made for the movie. But, even still, the movie is genuinely terrifying and it’s primarily due to the way that it is presented. Using hand-held cameras gives the film a stunning you are there feel, and the scares are generated more from the things unseen rather than what is seen. The “Blair Witch” herself is never actually shown, and it’s really up for debate if the movie concretely says if she’s real at all. But, it doesn’t matter in the end, because it’s the paranoia of not knowing everything that truly gives this movie it’s power.

Though revolutionary, The Blair Witch Project is not without it’s problems either. There’s little to no character development, and the dialogue can be groan inducing at times. And the quality of the film-making is not for everyone’s taste (hope you can get used to a lot of grainy shots of nothing but darkness). But The Blair Witch Project is less fascinating as a film and more interesting for what it actually affected within the industry. As a horror movie, it was something very new and original. In an era that was becoming increasingly dominated by Scream knock-offs, Blair Witch was a breath of fresh air. Here was a movie that didn’t need buckets of blood or music crescendos to drive the scary moments. All it needed was a sense of confusion and a bleak atmosphere. But, it’s legacy wasn’t just limited to the horror genre. What was also groundbreaking about The Blair Witch Project was the way it was marketed. The movie only cost $60,000 to make, but it ended up grossing $240 million worldwide, and that is because of how well it generated buzz before hand and how it spread by word of mouth. This happened in the then underground world of the internet, and it became the first ever viral marketing used to promote a movie. More than anything, this is the biggest legacy that Blair Witch has left, because every film now has followed it’s lead with marketing films through websites and online forums. In addition, the movie also launched a genre of it’s own that even extends outside of the Horror genre where it started; the found footage film.

Of all the things that would define the “digital era” of horror film-making, it would be “found footage.” In the wake of The Blair Witch Project, there were dozens of copycat films that would also try to capitalize on it’s success. Movies like Quarantine (2008), The Poughkeepsie Tapes (2007), and REC (2007), emerged in this time; some good, but mostly bad. For the most part, few movies could ever achieve the same novelty that Blair Witch had when it first released, but a couple of them still stood out. Paranormal Activity (2007) took the Blair Witch style and updated it with modern technology, giving the found footage sub-genre a more refined look. And then there were movies like Cloverfield (2008) and Chronicle (2012), which took “found footage” into other genres, showing the format’s versatility. More often than not, the success of these “found footage” movies hinged more on whether or not the films were actually good and entertaining enough, and less about how well they look, which is something that boded well for the format. “Found Footage” is better able to get away with a less polished look, which in turn made it a valuable genre to work within for the budget-minded filmmaker. Many up and coming filmmakers across the world find the “found footage” sub-genre as a great place to flex their film-making muscles, because it allows for more flexibility with the storytelling, as you are not tied to conventional Hollywood conventions. This was also the era when reality television was dominating the airways, with shows like Survivor and American Idol generating huge ratings, so “found footage” was perfectly reflective of it’s audiences’ new found fascination with documented reality, or the illusion of one. Whether or not Blair Witch is responsible for launching all of that, it nevertheless marked a big push forward for a film-making technique whose time had come.

But, “found footage” is not without its fault as a technique either. Too many young filmmakers tend to mistake the format as a film-making shortcut. It’s so easy to create a sense that you’ve made a Hollywood level film by just emulating the “found footage” movies that are released in theaters. But, more often than not, most “found footage” movies fail because they don’t have a compelling story behind them. Horror “found footage” films in particular have churned out some truly horrendous movies in recent years; so much so that there seems to have been a backlash by audiences, who are now demanding a different direction for the genre. This is largely due to the fact that for a while, “found footage” became a crutch for a genre that was lacking ideas, so Hollywood filmmakers used it to cover up the fact that they were just rehashing the same cliched elements over and over again. One particular sub-Horror genre that was done to death with “found footage” was the Exorcism and Demonic Possession films. These types of movies, such as The Last Exorcism (2010) and The Devil Inside (2012), especially squandered their potential by taking way too many film-making shortcuts that actually ended up insulting their audience. The Devil Inside was even documented to have elicited boos from multiple audiences because of it’s audacity to end with resolving a thing in it’s story and conclude with a plug for it’s website. It was at that point where audiences were seeing that there was no innovation in the genre with this kind of technique; it was just a way for hack horror filmmakers to quickly churn out a cheap product. And for a fan-base that was starved for something fresh in the Horror genre, this became a terrible blight on the ever evolving genre. If Horror movies were to reinvent itself, it would have to escape the shadow of the Blair Witches and the Paranormal Activities.

In recent years, we’ve seen this new tug-of-war in the Horror genre between the cheap “found footage” style, and the sleeker, more ambitious Horror. Nostalgia is something that has actually moved the Horror genre in a different direction, as many new filmmakers in the genre are looking more to slasher movies of the 70’s and 80’s for inspiration, and less to The Blair Witch Project. Recent critically acclaimed horror movies like The Conjuring (2013) and It Follows (2014), have brought back a more refined look to the genre, with thematic lighting, practical effects, and a grounded camera all making old fashioned techniques feel like new again. They are far more emblematic of the techniques of it’s 70’s and 80’s cousins, and in some cases, they even borrow the era’s aesthetic right down to the smallest details. It’s a clear sign of an audience coming of age and recognizing the value of something other than what the Hollywood machine has been churning out. What seems to be happening more now is that audiences have grown tired of the cheap amateurishness of “found footage” horror, and are instead looking for better scares from filmmakers who continually challenges their audience and makes the visual presentation just as important as the scares. Filmmakers like James Wan (The Conjuring) bring a lot to the genre because they know what they’re doing and they are not trying to hide their filmmaker shortcomings through gimmicks. And as we’ve seen not just in the movie theaters but also on television with the success of the Duffer Brothers’ series Stranger Things, this shift in the Horror genre is not just a little one, but a bigger mainstream move that will probably change the face of Horror for years to come, and mark the end of the “found footage” era.

But, that’s not to say that The Blair Witch Project‘s legacy will disappear entirely. “Found footage” is a technique that is actually finding it’s footing outside of the horror genre at the moment, and I believe that’s where it’s future will be. As we’ve seen before, “found footage” can be used for all sorts of different types of stories and depending on the subject, it actually becomes a refreshing and unexpected exercise in narrative. Cloverfield proved that visual effects and CGI would not look out of place with handheld photography, and Chronicle showed that the format could even tell a compelling story with a surprising amount of depth and tragedy. Comedies have even found a way to use the “found footage” technique to tell their story, with movies like Project X (2012) letting the POV perspective catch audiences with unexpected visual gags in a new way. And with better cameras out today, hand held photography can hold it’s own in cinemas just as well as other movies. Take for instance David Ayer’s End of Watch (2012), a movie that could have been filmed the conventional way, depicting the day to day lives of inner city cops (played by Jake Gyllenhaal and Michael Pena), but instead is shot documentary style with hand-held cameras, which gives it a distinctive look. Ayer’s stylistic choice turns out to have been a better one for the story he wanted to tell, putting us right in the middle of the action and in the process, within the mindset of his characters. It also calls to mind the kind of footage that you would normally see on a real police dash cam, or on shows like COPS, which is a direction you rarely see mined for dramatic purposes on film. So it shows that like the Horror genre that it was spawned from that the “found footage” sub-genre is evolving too, finding itself becoming a handy technique for unconventional storytelling.

That as it turns out is what The Blair Witch Project‘s lasting legacy will be over time. It didn’t invent the “found footage” technique, but it popularized it in a way that it became a genre on it’s own, one that doesn’t need to stick solely within the realm of Horror. Not only that, but it truly modernized the industry in ways that no one expected, including using the internet for film marketing. It’s hard to believe that this little micro-budget horror movie has had such a ripple effect on the industry, but it shows how valuable it can be to take steps steps outside of the normal ways of business in film-making and try something different. As a movie itself, it holds up as more of an oddity than anything else. Perhaps it’s the audacity of the project that we find so fascinating about it and how well it succeeded. I for one admire how effectively it used it’s little gimmick and created scary moments without having to resort to gore and violence for shock value. It’s also unmatched as a gimmick as well. Few others have managed to emulate the the visceral experience of watching this for the first time, although others like Paranormal Activity have successfully done their own thing with the same techniques. And the indie spirit of it is something that also keeps it appealing. We all saw how disastrous Hollywood’s version of it could be with Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 (2000); a clear example of a bigger budget producing lesser results. Within the Horror genre, Blair Witch still looms large, even as the genre changes again. Heather Donahue’s teary flashlight lit close-up is still on of Horror’s most iconic images. Overall, The Blair Witch Project proves that even small movies can have huge impacts on film-making, and be rewarded with a new genre that owes it’s whole existence to it.