Every era of film-making certainly has it’s trendsetters and generational voices who rise up and define the movies of their time. But most of the time, some filmmakers either diminish as their styles conflict with changing times, or they reinvent themselves by adopting a new style altogether. Very few filmmakers ever retain success all the way through their careers without compromising some aspect of how they make movies. Those that do change over time do run the risk of alienating some of their original fan base, but if the filmmaker is able to maintain the same amount of quality in their work throughout their careers no matter what film they are making, then they are able to illustrate their versatility and maintain their popularity. No director in the last half century has managed to navigate the highs and lows of a career in film-making better than Steven Spielberg. Without a doubt the most successful filmmaker of his time, and arguably the greatest one as well, Spielberg has managed to become a household name over his nearly fifty year career in Hollywood. And what is remarkable about his body of work in that time is not just the quality of his film-making, but also how well most everything he has made has connected with audiences. Both as a director and a producer, he is responsible for many of the most iconic films of the last 30 years. He’s brought characters like Indiana Jones to everyone’s attention; he made dinosaurs walk the Earth again in Jurassic Park (1993); he made everyone afraid to go back in the water again after Jaws (1975); and he made music with extraterrestrials in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). But, after creating so many imaginative moments that no doubt shaped the childhood memories of many a film-goer for years, he suddenly shifted his talents away from the realms of fantasy and towards a more grounded reality, all the while still always remaining true to his craft.

The story of Spielberg the filmmaker is one of two different eras, which could be summed up as before Schindler and after Schindler. While there is overlap between the two eras, with Spielberg experimenting in more grounded dramas in his early career (1985’s The Color Purple and 1987’s Empire of the Sun) and returning to more fanciful films from time to time in his later years (2002’s Minority Report, 2005’s War of the Worlds, 2016’s The BFG), it is clear that his directorial style made a dramatic shift with the release of Schindler’s List in 1993. The brutal, black and white portrayal of the horrors of the Holocaust was the most dramatic cinematic stepping stone that the once whimsical filmmaker had ever made, and since it’s release, Spielberg has focused his efforts as a storyteller towards true life stories with an often moral center at it’s heart. That’s not to say that he became a different director altogether. In fact, many of the techniques that he honed over so many years are still present in all his movies; only the subjects have changed. Stylistically he is just as innovative and creative behind the camera as he’s always been; it’s just now he’s more concerned with more serious subject matters. Essentially, his vision matured just as his audience did. Apart from the shift in his directorial tone, his style can also be defined by the gracefulness of his ability to visualize a story. For someone who had no formal film school education, it is amazing how well Spielberg understands the language of film, in some ways far better than most of his contemporaries. Spielberg doesn’t show off behind the camera; instead he immerses you into the scene, never directing your eye but instead allowing moments to play out in front of you. Like other directors I’ve spotlighted here, I’ll be taking a look at the techniques and themes that define most of Spielberg’s work, and illustrate just how much they have contributed to his unparalleled success in the industry.

1.

INSTINCTUAL DIRECTION

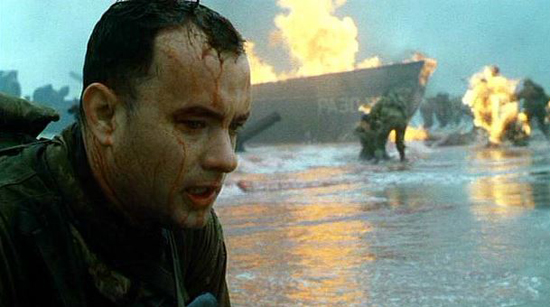

Unlike many of his peers at the time, Spielberg did not attend film school (though he had applied very hard to get into USC’s esteemed film program, where his good friend George Lucas attended). Instead, he had managed to secure an apprenticeship at Universal Studios which in turn led to him becoming the youngest director ever signed to a contract at the studio, at the age of 20. From this, he developed his skills working on episodes for many of the shows filmed on the Universal lot, which would go on to influence the way he would direct for the rest of his life. Spielberg, though responsible for some of the most lavish films ever made, is in essence an economical director, working within confines that allow him to retain full control of his work while at the same time grounding him with a sense of restraint. It’s clear that working on television budgets allowed Spielberg to innovate in order to work around those constraints and figure things out on the fly. It’s also to his benefit that he is a bit of a film buff himself, and carries a wealth of knowledge about the language of film purely from all the movies he’s scene. It’s because of this that even to this day, Spielberg is a director that is guided by his instincts on set more than anything else. He rarely does pre-visualiztion on his movies and instead chooses to block his shots on the day of filming, believing that his best ideas (and they often are) come to him in the moment while he’s observing the environment around him. This spontaneity is often what makes his movies feel more alive than most others. A prime example of Spielberg’s instincts manifesting in an unforgettable experience is the Omaha Beach opening of Saving Private Ryan (1998). According to Tom Hanks and other actors in the scene, they were basically directed to run up the beach without any warning about what they were going up against, with Spielberg following behind with a handheld camera. That chaotic situation is exactly what leads to the unforgettable mayhem that we see on screen, but even in less bombastic moments, Spielberg still finds his a way to let the camera absorb a scene in rather than force it through.

2.

THE SPIELBERG ONER

Which leads to the most interesting single technique in Spielberg’s arsenal; the oner. This is a shot that normally would be broken up into several different shots, but instead is allowed to play out with simple pans from one subject to another, alternating between stationary framing and moving framing. This is different from the more famous long tracking shots, which often call more attention to themselves. Spielberg’s oners often last no longer than a minute or so, but still represent a careful construction of visual storytelling that manages to relay all information to an audience without ever cutting away. There are many amazing examples of Spielberg using this technique in all sorts of movies; whether it’s in having his actors move across the setting while delivering dry expositional dialogue, or having one action play out in the background while another is being framed in the foreground. Most of the time, Spielberg uses these short little scenes to establish his settings and immerse the viewer into the moment, like Oskar Schindler’s introduction at a night club in Schindler’s List, or allow his actors to comfortably perform a scene without it having to be interrupted by a cut, like Daniel Day-Lewis’ lengthy monologues in Lincoln (2012) or Richard Dreyfus finding himself immersed in sculpting his mashed potatoes in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. And this is a technique that stems back to his television days, because it allows him to work with less set ups for shots, which ultimately makes the shoot less expensive and less time consuming. Oddly enough, his most complicated and prolonged production, Jaws, features some of the best examples of this type. When production issues regarding the mechanical shark plagued the shoot, Spielberg worked around it with using simple “in one” shots. There’s a remarkable one where the camera remains stationary in front of the actors, but is positioned on a moving ferry, allowing the background to change while the camera remains still. The famous reveal of the shark is also a wonderful example of getting everything in one shot for maximum impact, with Roy Scheider focused in the foreground and the shark appearing without warning behind him. They are short, but effective, and almost unnoticeable most of the time, which is a testament to Spielberg’s skill with how he uses his camera’s eye.

3.

WILLIAMS, KAHN, AND KAMINSKI

Most directors usually have their common collaborator who more than others have contributed to forming the characteristics of their signature style. Most often it’s an editor or a cinematographer or a go to actor that helps define a director’s body of work. Spielberg has uniquely kept his core group of collaborators intact for pretty much most of his career, pretty much through all departments. He often refers to his crew as a second family, and indeed his whole filmography is filled with the same names filling the final credits, showing his comfort with people he can trust on every project. Three collaborators in fact stand out as the ones who have done the most to define what makes Spielberg’s film what they are. The often least heralded but still fundamentally crucial part of Team Spielberg is his editor, Michael Kahn. Kahn has edited all but one of Spielberg’s films since Close Encounters, and is the one that most closely works with Spielberg through the storytelling process. Spielberg has often referred to him as the twin he never had, because of how like minded they are when it comes to finding the story through all the shots that they’ve assembled. Cinematographer Janusz Kaminski partnered up with Spielberg much later, first joining the team on Schindler’s List. Since then he has cemented what you could say as being the look of a Spielberg film, which often has a silvery glow to it with bright lighting, stark contrasts, and cool saturation of the colors. This style has been very helpful lately with Spielberg’s shift towards grounded historical features, because of the more naturalistic texture it brings. But, of course Spielberg’s whole body of work would have felt a whole lot different had it not been for the magnificent musical scores provided by the legendary John Williams. Arguably the greatest film composer of all time, Williams is responsible for majestic, iconic epic melodies, and many of his best work has been saved for Spielberg. I still get goosebumps when I listen to the Jurassic Park theme, and “Slave Children’s Crusade” from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) is probably my favorite piece of music from any movie ever. Spielberg’s talents as a director are great enough, but it makes it even better when you’ve got the best help in the biz by your side.

4.

SENTIMENTALISM

Spielberg can cover a wide range of emotion in his movies, and can make anything from childlike wonder to harsh, gritty terror a part of his narratives. But, at the end of the day, he is an optimist who wants to leave his audience with a sense of hope for the human condition and a level of comfort as they leave the theater. Some have argued that Spielberg’s films stray too much into a sentimental tone, sometimes making them a bit too saccharine and diminishing the power they could have had if Spielberg had been a little more cynical with his stories. It can be argued that Spielberg sometimes reaches a bit too far by indulging in some sentiment. This is very true in some of his lesser films, which often feel burdened by some of Spielberg’s indulgences, like the tonally confused Hook (1991) and A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001). Most of the time it shows the director trying extra hard to create what many refer to as the “Spielberg moments” which often are emotional moments punctuated with a small touch of whimsy. They are often Disney-like in their execution, and can at times feel out of place. But, when a “Spielberg moment” lands, it is quite often magical. You can’t help but love the wonder he brings to the first moment you see the dinosaurs close-up in Jurassic Park, or gaze in amazement as the mother-ship flies over Devils Tower in Close Encounters. He even brings needed sentiment into darker moments, like the girl with the red coat in Schindler’s List. But perhaps his most powerful use of sentimentalism can be found in E. T. The Extra Terrestrial (1982). From beginning to end, it is a story of a boy bonding with an alien creature and creating a deep friendship that ultimately must end. Telling this story through the point of view of a child, Spielberg had to make it as sentimental as possible, because of the childhood innocence involved. And because of that, the sentimentalism is very potent and elevates the story, making it almost fairy tale like in it’s execution. It also connects the audience so deeply with the characters, and by the end, the movie has earned it’s sentimental payoff, with one of cinema’s most emotional finales ever. It may be a weakness sometimes for Spielberg, but at the same time, no one does sentimental on film better than he can.

5.

FANTASY AND HISTORY

Spielberg may have written much of film history himself with the movies he has either directed or produced over the years, but he himself is informed by an appreciation of what cinema has been able to accomplish in all the years prior. He has said that the things that influenced him the most have always been cartoons and historical epics, and those are certainly apparent in the movies he has made over his career. He loves fantasy and humor, which he attributes to the magical beauty of Disney animation and the zany mayhem of Looney Tunes shorts. And many of his more fantastical films often carry with them a cinematic language that feels akin to animation. At the same time, he also felt inspired by Hollywood historical epics like Lawrence of Arabia, which illustrated how cinematic wonder could be derived from even grounded, true life stories. It’s these two areas of inspiration that have defined Spielberg’s interests as a filmmaker. He’s either Spielberg the dreamer or Spielberg the historian, and oftentimes, they feel like two different roads running parallel with each other. He goes back and forth, but each one represents two very different directions for Spielberg, while at the same time feeling like they are from the same mind. You do get some movies that overlap, like the gritty science fantasies of Minority Report and War of the Worlds, as well as whimsical grounded dramas like The Terminal (2004) and Catch Me If You Can (2002). But, often, the director is at his best when he sticks to one direction at a time. It’s especially interesting when he maneuvers effortlessly from one to another, sometimes in the same year, like 1993 with both Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List. Lately, he favors the dramatic over the fanciful, with some of his movies like Munich (2005) hitting some shockingly gritty depths that you never would have imagined from the sometimes playful director. But, it’s a testament to a filmmaker who is committed to making his choices of film more than just satisfying towards his indulgences, but also thoroughly honest to what they need to be, whether they transportative or informative.

I for one cannot imagine a life without a filmmaker like Steven Spielberg. The man is just a machine that keeps churning out one cinematic milestone after another. Imagine where cinema would be without movies like Jaws, E.T., or Jurassic Park and all the innovations they made along the way. He also sparked conversations worth having with his insightful historical dramas. A much needed spotlight was cast on the memories of Holocaust survivors after the release of Schindler’s List, and since then so many more of them have shared their own stories, making an essential document of one of history’s darkest moments all the more detailed. World War II veterans were also finally able to have their true, horrific experiences finally realized on film with Saving Private Ryan, and allow for many of them to finally open up about the true costs of war that they had seen for themselves. And even beyond the movies, Spielberg is a tireless champion of cinematic innovation and expression. Indeed, most other filmmakers my age can attribute much of our own inspirations to one or more films that Spielberg has had his hands in. He is not one for flashiness, but his impact on all cinema is undeniable. We all have that one “Spielberg moment” that is forever ingrained into our psyche, whether it’s the bicycle crossing the face of the moon in E.T., or the ripple in the glass of water from Jurassic Park. And the while he is a director that has matured over time and gotten a bit more serious, he’s still one who embraces the innocence of the past and finds ways to liven up his movies with a sense of wonder, no matter what story he is telling. Even in these next couple months, with his new film The Post opening wide this week and Ready Player One only a short couple of months away, he is continuing to fulfill both aspects of his style in ways that are both satisfying to him and his base of fans. We are likely to see that continue for many years to come, and it’s great that our generation has had a voice like his so linked to the concept of film as being both art and entertainment, which in turn has become the driving method of our modern cinematic world.