The magic of cinema is the power to transport the viewer to another time and place. We can sit back in our seats at a local cinema or lounge in front of the TV in our living room and have the world around us slip away once we settle in and let the movie grab a hold of us. To audiences, the movies are alive. A lot of work goes into pulling off that magic trick, whether it be the effectiveness of the production and costume design or the authenticity of the actor’s performance. But, if there is one aspect of film-making that sometimes goes unheralded, it’s the effectiveness of the setting itself. Yes, a lot of artificiality is involved in staging a scene in a particular place, especially when shooting entirely indoors on a manufactured set. But, there are quite a few movies that use the natural world for the setting of their movies, and just as much consideration goes into finding the right location for a film as it does finding the right actor for a role. There are many movies where the setting plays a crucial role in the story, and in many cases, is often a character unto itself. It may not be an active player, but you will often find movies where the setting is either a threat to our main characters, a safe haven, or a place of endearment that is valued by many. A place can also have it’s own personality, based on the collective characteristics of it’s inhabitants. But, when the importance of location is not taken into consideration, it can often reflect poorly on the identity of it’s own story. Over the years, we’ve seen many amazing locations presented in movies, but not enough has been said about the work that goes into making those same locations an integral part of a movie’s success.

Producing a film often starts with the process of location scouting. Often supervised by the directing team itself, finding the right locations for a movie is important for finding the vision for a story-line. It’s one thing for the filmmaker to have an idea in their mind of what their setting will look like and how the story will progress within it, but it’s another thing to actually see it in person. Blocking a shot takes on different challenges when done in the real world. A director must deal with details and obstacles that normally wouldn’t occur on a controlled set, and this often leads to some interesting directorial choices. Sometimes, a story can even drastically change in the development process when a location is found that presents a whole bunch of new possibilities to the filmmakers. And it’s largely a part of the way that a location lends itself cinematicly in different ways. It can either be the embodiment of one particular place in your story, or can act as nowhere in particular but serve your needs. Sometimes you want a setting that looks unlike anything you’ve ever seen, but can also have that chameleon like ability to be any number of places. It’s all to the discretion of the filmmakers. Because of the importance of a location’s impact on a story, they often have to be more carefully chosen than the actors that inhabit it. And, as we’ve seen in many important and monumental films, locations and setting often make these movies stand out and retain their own identity.

Some filmmakers choose to use their movies not just to tell the story of their characters, but of the specific places themselves. Most of the time, they are love letters to a filmmaker’s hometown or place of origin; most often a major city or a cultural region. Directors do this intentionally for the most part, but sometimes it just comes as part of the filmmaker’s own style. New York City is often presented as a crucial part of many film narratives; probably more so than any other place in the world. One particular filmmaker, Woody Allen, created an identity as a director by using the Big Apple in so many of his early films, identifying himself with New York while at the same time presenting an loving image of the city through his own cinematic eye. Films like Annie Hall (1977), Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), and Bullets Over Broadway (1994) probably wouldn’t have the same impact if they weren’t set within Woody Allen’s own idealized version of New York, which is often as quirky and unpredictable as the man himself. His Manhattan (1979) in particular is almost the very definition of a love letter to a single location. But, as much as celebrates the city through it’s wondrous aspects, there are other filmmakers that celebrate New York in less glamorous ways. Spike Lee presented New York as a grittier place in his 1989 masterpiece Do the Right Thing, which depicted the racial tensions that undercut much of the daily life in the city between law enforcement and the poorer black neighborhoods. Though far from the idealized New York of Woody Allen’s movies, Spike Lee’s NYC is no less a potent character in his movies, and Lee celebrates the vibrancy of the people who inhabit it, and likewise celebrates the indomitable spirit of the city’s often forgotten poor. It shows how much a single place can carry so much character in a movie, even through different kinds of perspectives.

It’s another thing altogether to take a location and make it someplace that exists nowhere else in the world in a believable way. What I’m talking about is recreating a place from a work of fiction by using real locations in different areas and stitching them together to create the illusion that it’s all one place. This is a trick that’s been used in Hollywood for many years, but has grown in complexity as film-making tools have improved. Through the magic of editing, you can make real world settings become anywhere you want it to be. This is often used to great effect in comic book movies, where New York City has on more than one occasion played the role of Metropolis in the Superman franchise. It helps to give extraordinary stories like those a more grounded reality, which in turn helps to transport the viewer more effectively into these fictional worlds. One of the filmmakers who has done this to spectacular effect is Christopher Nolan, who is renowned for his insistence on real world authenticity in his epic scale movies. He showed his expertise with this effect when he chose real world locations for his Dark Knight trilogy. Sometimes his choices of location were pretty obvious to pin down (Downtown Chicago acting as Downtown Gotham City in The Dark Knight’s spectacular chase scene), but there were other scenes that displayed quite a bit of ingenuity to make the fictional Gotham feel real. In The Dark Knight Rises (2012) Nolan managed to combine three different cities into one chase scene and make the audience feel like they were authentically taking a tour of a real Gotham City. It was when Batman chases the villainous Bane on motorcycles, with the on-location shooting starting on Wall Street in New York, heading through the underground tunnels of Chicago, before ultimately ending up in Downtown Los Angeles. That’s a spectacular use of multiple locations to make a fictional one feel as real as possible, and as a result, it gives it a more authentic impact to the story.

But this kind of technique isn’t just limited to giving a fictional place authenticity; it can also allow for a filmmaker to create any world they want, no matter how otherworldly, and still make it feel real. Inspiration can often come from the natural world in this sense, as the camera can transport the viewer anywhere, but with the story filling the context, and not the location. Natural wonders across our planet, especially obscure ones, often play the part of different worlds, and these are locations that are given special consideration during the scouting phase. In the fantasy and science fiction realms, a location has even more influence with the shaping of a story than anything else, so the better you can present it on film, the better. This is a case where locations must have that trans-formative effect to look unlike anything we’ve ever seen, but still come off as believable, and this often leads to some very complex planning on the filmmakers part. Peter Jackson managed to this spectacularly well with his Lord of the Rings and Hobbit trilogies, where he found the ideal locations to make J.R.R. Tolkein’s Middle Earth come to life through the natural beauty of his own native New Zealand. New Zealand was a mostly untapped source for location shooting before these movies came out, but with Peter Jackson’s vision, he managed to showcase it in a spectacular way, while at the same time authentically visualizing the wonders of Tolkein’s world in there as well. It’s much better to see the Fellowship of the Ring climbing real mountains than recreating it on a stage with visual effects. As a result, a natural looking Middle Earth became just as much a part of that movie series’ success as anything else, and that same devotion to detail is influencing many more movie projects today, not to mention boosting New Zealand’s tourism industry significantly.

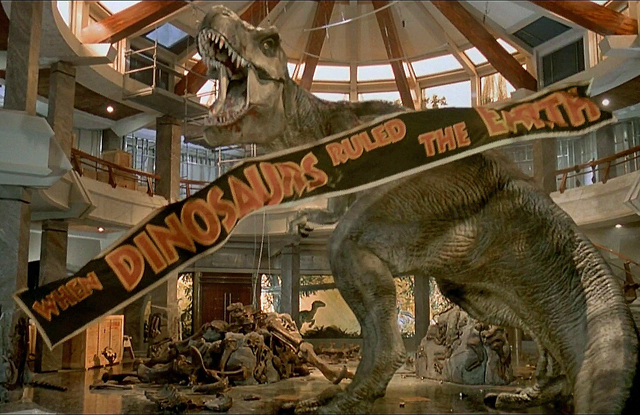

But, it’s not just the expanse nor the many layers of a location that helps to make it a significant factor in a story. Sometimes a single iconic look to a place can drive the story along as well. Some movies can even be identified by a single iconic structure or a scene that utilizes the most unbelievable of settings. The Bradbury Building, for example, is a real place in Los Angeles known for it’s amazing interior ironwork within it’s atrium. The location has been used in many movies, but none more memorably so than in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), where it served as the location for the climatic showdown in that dystopian futuristic classic. It’s a great example of using an iconic location in a nontraditional way, and as a result, giving it a whole other identity in the story than it’s own real purpose in reality. But, no other filmmaker made use of iconic locations in his movies better than Alfred Hitchcock. Locations have always played a crucial role in his stories, even during his early years in Britain when he used the Scottish Moors so effectively in The 39 Steps (1935). After coming to America, Hitchcock became enamored with the many different types of iconic Americana in our society and all of his later movies would highlight much of these in both spectacular and sometimes even subversive ways. Some of them are pretty spectacular, like Kim Novak’s attempted suicide by the Golden Gate bridge in Vertigo (1958), or the thrilling chase across Mount Rushmore in North by Northwest (1959). But, Hitchcock would also make minor locations take on identities of their own; including the most frightening roadside motel ever in 1960’s Psycho. As often the case with these movies, it’s the singular location that stands out, and more often than not, it defines the movie as a whole. In the case of Psycho, it’s the Gothic mansion that’s becomes the selling point of the movie, and not the actors, which tells you a lot about the power that an iconic location can have on it’s audience.

Though a lot of movies take into consideration the importance of a location, a movie can also run the risk of feeling too disjointed from one as well. Filmmakers sometimes do not see the importance of a location when they are working on a much smaller scale, but they run the risk of limiting their storytelling options that way. A setting can reveal many different things about the characters, sometimes in unexpected and unplanned ways. It’s a part of piecing together the character’s life outside of the narrative; revealing to us how they live day to day within their larger world. Showing that a character lives in the city may hint at a more cosmopolitan side to their personality, or if they come from the country, perhaps they have a more laid back and simple outlook on life. If your character is from Genericsburg U.S.A., then it’s more likely that they will have no defining characteristics to them at all. In the movies, a character is defined by their surroundings more than anything else, and that’s why a setting is often the most important supporting factor in their story. Authenticity is also a huge factor, especially when audiences can tell when a movie is accurately reflecting a real location or not. One of the worst examples I’ve ever seen of using a location in a movie was in the film Battle Los Angeles (2011). Speaking as someone who lives and works in LA, I can tell you that this particular film in no shape or form looks and feels like it’s in the real city of LA. And that’s because not a single frame of it was shot there. The whole thing was filmed in Louisiana, with sets constructed to look like streets in Los Angeles and nearby Santa Monica. Unfortunately, it robs the film of it’s character by feeling so fabricated. As a result, it’s a generic action flick that will tell you nothing about the city of LA, showing the downside of not treating your location with the respect it deserves. You want an authentic portrait of the city of Los Angeles, watch some of Michael Mann’s films like Heat (1996) or Collateral (2004).

It may not be apparent from the first time you watch a movie, but the setting of the story plays perhaps the most crucial role in it’s overall effectiveness. And it can be through specific intention on the filmmaker’s part, wishing to highlight a specific place, or by finding a setting that perfectly supports the action and characters that exist with it. It is the silent supporting player in a movie’s plot and can surprisingly be the thing that most movies hinge their success on. Any filmmaker who values the process of capturing a sense of reality in their movie will tell you how much they appreciate the variety of cinematic choices they can have when they find an ideal location. If the location is interesting enough, anywhere you point your camera will reveal new things for the audience, helping to enrich their experience. When I was working on sets back in film school, I often enjoyed the location shoots much more than the ones in a studio. A real, authentic location just has a lot more variety, even when it isn’t meant to represent no particular place. One of my favorite location shoots was on a film set called Four Aces, located out in the Mojave Desert, about a 2 1/2 hour drive from Hollywood. It’s been used for films like Identity (2002) and Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003), plus a dozen other music videos and commercials, as well as the student movie that I crewed on. What struck me is how this fabricated set made to look like a gas station with an attached diner and motel out in the middle of nowhere could be so many different things, and yet almost always stand out with it’s own identity no matter what movie project it was in. That’s the power of having a great location in a film. Locations are sometimes the most important supporting character a movie can have, and they become so without saying a single word of dialogue.