You’ll never go in the water again! That was the tagline of the monumental blockbuster film Jaws (1975) when it first premiered, and was there ever a tagline that hit it’s mark exactly as it did. Hollywood was no stranger to creature features. The whole B-Movie Sci-Fi craze of the 1950’s and 60’s was littered with movies about mankind battling the forces of nature as they run amuck. But, Jaws was very different from those classics of the past. It was grounded and devoid of campy cheapness. It was a film that managed to transcend the the creature feature genre and grab a hold of it’s audience in a way that the industry likely did not expect. It was a movie that made it’s premise feel real, and for a time, it did in fact make people afraid to go into the water. Jaws was adapted from a novel of the same name by Peter Benchley, who had a part in adapting his own book into the screenplay alongside screenwriter Carl Gottlieb. While the story had some of the same tropes as many other creature feature stories, Benchley’s novel rooted it’s premise in a far more grounded story about the people charged with saving their town from a rabid great white shark. It’s a simple story, but enriched with not just the man vs. nature aspect but also with the friction that occurs between the people involved as they embark on their quest. It’s just as much a character study as it is a story about hunting a shark. While the movie had a lot of potential to be a fun action adventure, it would achieve a much greater status in the annals of movie history by falling into the right hands at the right time. Jaws status as a classic is inexorably tied to the personal growth of the filmmaker who made it; Steven Spielberg. Jaws was the movie that propelled him to the next level as a filmmaker and he wouldn’t be the icon that he is today 50 years later had it not been for the trials the he was put through in the making of this movie.

Steven Spielberg was an ambitious go-getter right from the start of his career in Hollywood. Legend has it he snuck off of the famous Universal Studios tour when he was a teenager and wandered around on his own. He was spared from disciplinary action after a film librarian at the studio was impressed by his ambition and he was granted a three day pass to revisit. That three day pass expanded into a full time gig as Spielberg became a regular assistant on the studio lot. He used his odd jobs to help finance a short film called Amblin‘ (1968), which got him noticed by a Universal executive named Sid Sheinberg, who signed the then 20 year old filmmaker to a 7 year contract. Spielberg would direct several episodes of TV series made on the Universal lot, and he won high marks for his professionalism and ability to run productions on time and on budget. Spielberg eventually got his chance to direct feature films for Universal, which included the critically acclaimed films Duel (1971) and The Sugarland Express (1974). But while these movies were well regarded, Spielberg hadn’t had that big break out hit that would turn him into a household name and give him the creative freedom to do what he wanted as a filmmaker. Thankfully, he still had the favor of Sheinberg, who by 1971 had elevated to the position of President at Universal Studios. And it was not long after that the novel Jaws was optioned by the studio. Based on Spielberg’s success with the movie Duel, which featured a story about a man being hunted by giant freight truck, Sheinberg believed that Steven had what it took to make this story about a killer shark work on the big screen. Spielberg was more than happy to take up the challenge, but given what happened over the next couple years, Spielberg may have had some second thoughts about the assignment.

The making of Jaws was to put it lightly a bit of a “shit show.” As skilled as Spielberg was up to this point, he had yet to make a movie as complicated as this one. For one thing, half of the film was going to be set out in open water. While you could do some of that on a studio controlled flood tank, of which Universal actually has one of the largest in the world, Spielberg believed that you needed the authenticity of being stranded out in the middle of open sea to really convey the terror of the shark’s presence. So, the production set up shop in Martha’s Vineyard, with the small island community playing the part of the fictional Amity Island from the novel. The sleepy, tightly knit community provided a good setting for the production of this movie, but it also was a crucial lifeline for the film once it moved into it’s oceanic phase. In order to make it look like they were out in open water, they had to film several miles out in order to make the island disappear over the horizon. But Martha’s Vineyard also had the benefit of having shallow waters all around it in a twelve mile radius, with the bottom being only 30 feet below the surface, making salvaging much easier if something went wrong. And that it did. Not only were they confined to filming on boats for most of the film shoot, but they were also dealing with three mechanical sharks that would be playing the monster. Two of the sharks were open on opposite sides in order to create greater mechanical movement depending on the shot and the angle they were capturing it from, while the third was fully skinned and meant to bob up and down in the water, mainly for the shots showing it swimming. But these sharks would prove to be a nightmare to maintain. Filming out in the open sea meant that the salt water would constantly wreck havoc on the mechanical instruments puppeteering the sharks, and the sharks would constantly experience multiple issues that delayed shooting for extensive lengths of time. Salvaging the sharks from the sea floor was also a common occurrence. The shark problems being a constant nuisance throughout the film shoot caused Spielberg to jokingly name the sharks Bruce, which was the name of his lawyer.

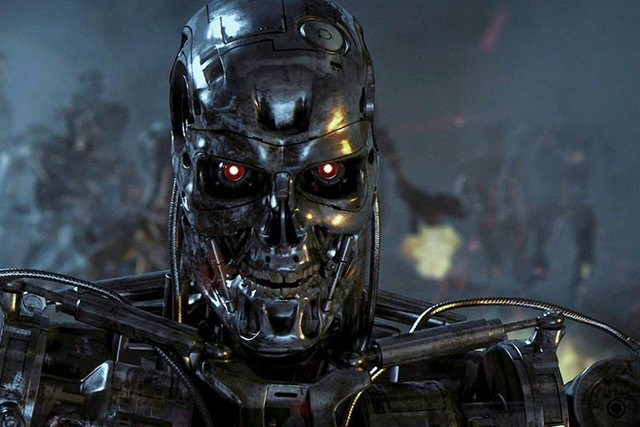

Given all the production woes, Spielberg was constantly worried that he might have the project taken away from him. He had gone from delivering on time and on budget to massively going over schedule by weeks. But, it was through these trials that Spielberg really found himself as a filmmaker, developing skills that would carry him through the rest of his career. While the sharks were giving him trouble, Spielberg used this opportunity to become a problem solver. He would fill the down time between shooting with the sharks by working on shots that would build the atmosphere of the movie. His team devised a scene that was not in the original script where Richard Dreyfuss’ character Hopper conducts an underwater investigation of a boat that was potentially attacked by the shark. The scene is famous for a jump scare as a severed head pops out of one of the holes in the haul of the boat. So while the scene doesn’t show the shark itself, you still get a sense of the terrifying power it holds after seeing what ends up to it’s victims. And through all of this, Spielberg learned that it actually worked to the movie’s benefit to show as little of the shark as possible, which helped to make the shots later in the film when he does appear have a lot more impact. They would only be able to get a handful of shots of the sharks actually working, but they would not be wasted, and thanks to the expertly handled building of dread throughout the film, Spielberg achieved his goal in making the shark absolutely terrifying. It’s all a trick of signaling the presence of the shark without actually seeing him. There are several underwater shots that signify the shark’s point of view as we see him swim up towards his victims who are bobbing around on the surface. Then the movie cuts to the actors as they react to the shark capturing them in it’s razor sharp bite. Couple this with John Williams’ iconic pulse-pounding musical score that signals the dreaded presence of the shark, and you’ve got a perfect recipe for making us forget that this is just some mechanical shark. In the end he becomes almost as terrifying as the real thing, and we only ever get 4 total minutes of screen time with him.

But it’s not just the shark that makes Jaws an iconic movie. Steven Spielberg also lucked out in getting the right actors for the part. An interesting side note about the director’s history with the source novel is that when Spielberg first read it, he found himself rooting for the shark because he found the human characters so unlikable. One of the great things about this movie adaptation is that Spielberg managed to make the human characters relatable and worth following to the end of the story. And it mattered to have the right actors in the rolls too. Roy Scheider was already a well respected up to this point in his career, having already garnered accolades for his work in the Oscar-winning The French Connection (1971). He would provide the perfect everyman element to the character of Sheriff Brody. Rising star Richard Dreyfuss would also bring a wonderful kinetic energy to the film as the cocky, self-made shark expert Hooper. The working experience between Spielberg and Dreyfuss must’ve really been fruitful as Spielberg would cast him as the lead in his next film, Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). But perhaps the most memorable character to come out of the film was the mysterious Captain Quint, played by an absolutely magnetic Robert Shaw. Quint enters the film with one of the most memorable introductions in movie history, scrapping his nails across a chalk board in order to get the townsfolk’s attention at a community meeting, and with his salty Irish brogue he delivers a character that’s as tough and mean as the shark he hunts. With echoes of Moby Dick’s Ahab, Quint becomes just as much of a wild card in the story as the shark, and his dynamic in contrast with the two more pragmatic heroes helps to give the movie personalities that are indeed capable of being interesting, independent of the shark. One of the greatest additions to the film’s story is the scene where the three men have a bonding moment in between shark attacks and share their own stories to each other. Here, Quint tells the other two about his time on the ill-fated U.S.S Indianapolis; a ship famous for sinking in shark infested waters after delivering the atomic bomb to the navy posted in the Pacific. The monologue Quint delivers, which was written by an uncredited John Milius, is chillingly told by Robert Shaw, creating one of the movie’s most iconic moments. Through that and many more moments like it, Spielberg managed to make this more than just a creature feature, but a truly human story about survival in the face of overwhelming terror.

In the end, the movie went overschedule by a staggering 100 days. Spielberg was worried that this would be the movie to end him, just as he was finally starting to get a foothold as a filmmaker. No studio would ever hire a director who ended up going three times over schedule like that. While he still had the favor of Sid Sheinberg at Universal, that might’ve ended as well if the movie failed to recoup it’s costs, which also went massively over budget. This was going to be the final film on his contract anyways, and there would be no need to renew if they couldn’t trust him anymore. So, with a lot weighing on his shoulders, Spielberg would assemble his film together in the editing room, hoping that all that hard work translated into a coherent film. The movie was orignally slated for a Holiday 1974 release, but because of the delays that the film shoot suffered, Universal had to push the release to Summer of 1975. This was seen as a bad omen for the movie. Back in those days, summer was seen as a dumping ground for the movie studios as films that were always considered valuable were released towards the end of the year, hoping to garner awards attention. Summer movies were the throwaway genre flicks that the studios didn’t see much value in since they never grossed as much as the prestige films. But, things would be different for Jaws. The delay almost became a blessing in disguise because it not only gave Spielberg the right amount of time to assemble a stronger movie out of his edit, but by the time the film was released, it would be playing in a less crowded field at the box office with no relative competition. The film opened on June 20, 1975 in one of the widest releases seen up to that point. Initially wide releases were reserved for maximum saturation for films that studios had no faith behind, but for Jaws, a movie that received instant critical acclaim and wide audience interest, it would be a foundational shake-up for the industry as a whole. Jaws became a monumental success at the box office, shattering every record in the books, including becoming the first film ever to cross the $200 million mark in it’s original release. Jaws not only was a success story, it also fundamentally changed Hollywood forever.

If there was anything that has come to define Jaws in the annals of movie history, it’s that it started what would later become known as the era of the Blockbuster. While Jaws wasn’t the movie that helped to coin the term blockbuster, as previous films like The Sound of Music (1965) and The Exorcist (1973) also were given the label, it was nevertheless seen as the movie that would usher in a new era where movies like it would be the driving force in the commerce of Hollywood. After the fall of the old studio system and the rise of New Hollywood, the driving force in Hollywood through much of the 60’s and 70’s was auteur driven films from the newest crop of maverick filmmakers like William Friedkin, Brian DePalma and Martin Scorsese. Spielberg came up through this generation, but he was also set apart from it given his studio connections. With the success of Jaws, the studios began to fall out of favor with the auteur driven cinema of New Hollywood, which was already starting to see declining returns due to out of control productions like Sorcerer (1977), Apocalypse Now (1979) and Heaven’s Gate (1980). Now they wanted to have the next Jaws. There were plenty of cheap copycat movies that tried to capitalize on Jaws success, like Orca (1977) and Piranha (1978), but it wasn’t another Jaws clone that would continue the Blockbuster era into the next decade. Spielberg’s friend and colleague George Lucas would follow Jaws’ example by releasing his new space opera adventure film Star Wars (1977) in the summer season, and in the end, he too would see a phenomenal success during it’s release, even surpassing the record setting grosses of Jaws. In the years that followed, the Summer season was no longer viewed as Hollywood’s dumping ground, but would instead be where Hollywood would premiere their biggest tentpoles, capitalizing on audiences off all ages that were out of school and looking to cool off from the summer heat. And both George Lucas and Steven Spielberg would continue to feed the studios’ appetite for new blockbusters, delivering more in the coming decades with big franchise like Indiana Jones, Back to the Future, and Jurassic Park. But all of this change was the result of the turning point that Jaws marked with it’s massive success in the face of all the factors that worked against it.

Steven Spielberg may have been the man who sparked the beginning of a new era in Hollywood, where the Blockbuster would come to dominate, but Jaws was also the movie that forged him into the kind of filmmaker that would continue to survive and grow in the changing Hollywood landscape as well. The challenging and mostly frustrating production of the movie would be his trial by fire as a filmmaker, and out of it he developed problem solving skills that have made him the most consistent and reliable filmmaker in the business. Spielberg became the great instinctual storyteller that he is today thanks to the creativity he had to rely upon in order to make Jaws come together. And even after 50 years, Jaws still is the thrill ride that brings you to the edge of your seat and hasn’t lost any of it’s, shall we say, “bite” over the years. It’s gone on to have this legendary aura around it, becoming one of the most oft-quoted movies in Hollywood history, especially with Roy Scheider’s now iconic ad-libbed line, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.” You can still see regular screenings of this film in cinemas all over the world, including a recent one at the TCM Classic Film Festival in April where it played with a pristine 35mm print at the Egyptian. It also has managed to become a mainstay at the Universal Studios lot in Hollywood, where the Studio Tour has a brief encounter with Bruce the Shark as a part of it’s showcase. But that’s not the only lasting legacy of Jaws at Universal. While Spielberg has gone on to make movies at every single studio in Hollywood, he still considers Universal his home base, and when he set up his own production company Amblin Entertainment, he chose to set it up on the Universal lot, next to the bungalows that he once worked out of as a page boy and assistant all those years ago. You can still see Amblin’s offices just off the main route of the Studio Tour to this day. Jaws made the Spielberg that we know today, and though it may have been a nightmare at the time, there’s no doubt that Spielberg is proud of what he accomplished with the film. Those grueling 150 days of shooting set the stage for the next 50 years of Spielberg’s life and he’s still not done yet. We may have been afraid to go back into the water that fateful summer, but we’ve always returned back to this movie again and again, and that will continue for the next 50 years as well.