The Criterion Collection is known for being the distributor of some of the greatest and underseen classics of yesteryear, but they also have a reputation for putting out modern films as well. In fact, if you look at the complete collection entirely, you’ll see that a good percentage of the titles are ones from the last 20 years or so. This does open up the debate over whether or not the Criterion Collection has a high enough standard over which titles it includes, considering the fact that it takes time for a film to earn the status of a classic. Some of Criterion’s more controversial choices for inclusion in recent years have included the films of David Fincher (#476 The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, #627 The Game), a film by Girls star and creator Lena Dunham (#597 Tiny Furniture) and also the movies of Michael Bay, I kid you not (#40 Armageddon, #107 The Rock, both now out of print). This begs the question of what makes a film a classic and if Criterion are the ones responsible for making that decision. I’m sure that Criterion would themselves say that they choose titles not because of their status as a classic, but on whether or not it’s a title that will sell well in the video market. The fact that they devote so much time and effort to make the editions of their titles so good is one of the things that has set them apart. And the reason why they choose to release films from contemporary directors is so that they can get the filmmakers’ actual input on the release of their films in the collection, as well as their approval.

One director who has not only had his whole filmography released under the Criterion label, but has also had his career boosted by the Collection as well, is Texas-born filmmaker Wes Anderson. Anderson is a very polarizing director, mainly due to his very distinctive style. His films usually are identified by their quirky story-lines and characters, their unconventional use of pop songs (mainly from the 60’s and 70’s) to underscore a scene, the bold use of colors and deliberate composition in the cinematography, and last but certainly not least, the presence of the great Bill Murray. Some people either love Wes Anderson’s movies in all their eccentricities, or loathe them as being nothing more than style over substance. While I can see how some people dislike Wes Anderson’s style, I for one can’t get enough of it. I have yet to see a Wes Anderson film that I didn’t like; even the one that left me a little underwhelmed (Criterion #450 Bottle Rocket) was one that I could still appreciate. And part of what has made me a fan of Wes Anderson’s work has been the excellent Criterion releases devoted to his films. So far, six of his movies have been released as part of the Criterion Collection: the aforementioned Bottle Rocket (1996), #65 Rushmore (1998), #300 The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), #540 The Darjeeling Limited (2007), and coming next February, #700 Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), which was my personal pick for the best film of 2009. One film in particular does stands out, mainly due to it’s early popularity, as a film that really began to define Wes Anderson’s status as a filmmaker: that being #157, 2001’s The Royal Tenenbaums.

The movie follows the struggling relationship between members of an affluent, but fractured family. The patriarch, Royal Tenenbaum (a perfect Gene Hackman) finds that the funds that have helped to support his decadent lifestyle have been drying up, and this leads him to turning back to the family that he had all but cut ties with years ago. The once proud family, made up of three former “wonder kids” now in their adulthood, are also struggling to take control of their lives. Chas (Ben Stiller) a Wall Street hot shot in his youth, who’s now struggling to keep everything afloat as a single father after his wife had died in a plane crash. Adopted daughter Margot (Gwyneth Paltrow) gave up a promising career as a playwright in order to settle down in a now loveless marriage with psychologist Raleigh St. Clair (Bill Murray). And Richie (Luke Wilson), the youngest, had a promising career as a tennis phenom, before he began to lose his game and faded into obscurity. Etheline Tenenbaum (Angelica Huston), the mother, has manged to keep her house in order despite the hard times with the help of her accountant Henry Sherman (Danny Glover), who has suddenly shared his growing affection with her. This prompts Royal to step in and reclaim his family before he loses them forever. And how does he do this? By telling them all that he’s dying of cancer, which is a flat out lie.

The film is a loaded one to be sure, and I wouldn’t disagree that Wes Anderson sometimes struggles to keep everything in check over the course of the run-time. But, The Royal Tenenbaums is nevertheless a very effective and charming movie. What makes it work so well, no doubt is the cast. Gene Hackman is outstanding as Royal Tenenbaum, and he steals every moment he’s on screen. What I love is the fact that Royal is so likable in this movie, even when he’s doing and saying the most horrible things. Wes Anderson’s scripts, which he co-writes on every movie (this time with co-star Owen Wilson), are known for their sly, and rather outlandish sense of humor, and no character better exemplifies that than Royal. I especially like the way that he takes little consideration of other peoples feelings, even when he’s in direct conversation with them. An awkward exchange with Chas at a cemetery in particular is both an uncomfortable and laugh-out-loud funny moment in the movie (“Oh, that’s right. We’ve got another body here.”) Gene Hackman alone would been enough to watch this movie, but the rest of the cast is also excellent. Angelica Huston brings a lot of class to the character of Etheline and helps to give the film its moral center. Gwyneth Paltrow is hilariously deadpan as Margot. Ben Stiller and Luke Wilson deliver some of their best performances as well. And Anderson regular Bill Murray is absolutely hilarious in his few moments onscreen. Add in Owen Wilson as ticking timebomb next-door neighbor and author named Eli Cash, and you’ve got a very well rounded cast.

If the film has a flaw, albeit a minor one, it’s the fact that it feels unfocused. I mainly see this as a byproduct of trying to fit too many things into one film. The cast of characters is enormous, and trying to give everyone enough screen time is a daunting task for any filmmaker. The Royal Tenenbaums was made in the early part of Wes Anderson’s career, at a time when he was still figuring things out. Looking back on the film, you can see that his style was still forming at this point in time. The Royal Tenenbaums would be Anderson’s last film to feature a kind of naturalistic aesthetic look to it, as he began to head in a much more whimsical and cartoonish direction with his next film The Life Aquatic. I think that the more subdued visuals of Royal Tenenbaums is probably why this film has remained to date one of Wes Anderson’s more popular films. It’s undoubtedly his most mainstream film to date, though The Royal Tenenbaums is not a conventional Hollywood movie by any means. But as a part of his overall body of work, I see this movie as one of his lesser efforts. I still love it, don’t get me wrong, but when I think of a Wes Anderson movie, this is not the one that comes to mind. I think of his later films as being the ones that really define him as a director, given how much more assured they are. But, I am glad to see how well this film has held up both as a movie and as a part of the director’s full oeuvre.

What is significant about the Criterion edition of this film is the fact that it was released as part of the collection almost instantly. Like I had said before, sometimes it takes a while for a film to achieve classic status, and only then it may find it’s way into Criterion’s catalog. The Royal Tenenbaums, however, was selected to be a part of the collection right when it left theaters; the shortest window ever for a Criterion title. The choice was made probably because of the fact that Wes Anderson’s previous film, Rushmore, sold so well under the Criterion label in the years after it’s premiere. Adding The Royal Tenenbaums seemed like a no-brainer choice, especially after it’s own successful run in theaters. But, what’s even more remarkable is the fact that Criterion had the exclusive rights to the film’s DVD release, thanks to a deal with Touchstone Pictures who financed the movie, and they made the movie available to the mass market. You have to understand that this was an unusual move on Criterion’s part. Up until that point, Criterion released their titles in small quantities and usually limited the availability to a few select retailers nationwide. In my home town, I would usually only find a Criterion movie section in my local Barnes & Nobles, and that was it. So, the fact that The Royal Tenenbaums was so widely available was a significant game changer for both Wes Anderson and Criterion. I’m sure that for many people, Royal Tenenbaums had to have been their first Criterion title, which opened up the gates for a whole new audience for the distributor.

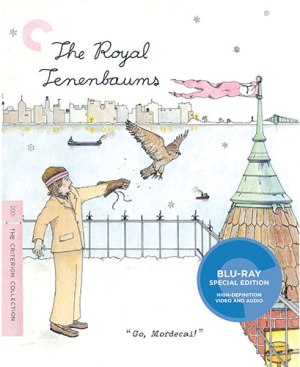

The Royal Tenenbaums DVD release back in 2002 was an enormous success, making the movie one of Criterion’s best-selling titles. Last year, they revisited the film again with a Blu-ray edition, which helps to give this 12 year old film a fresh new look. The movie is stunning in high definition, as is every other Wes Anderson film. This is probably why the director has become a favorite among Criterion collectors like myself; his bold use of colors brings out the full potential of the color range and brightness in a Blu-ray presentation. The blu-ray edition also carries over every bonus feature from the previous DVD release. Among the extras found here are a Director’s commentary by Anderson himself. There’s an interesting filmmaker profile of Wes Anderson made by none other than acclaimed documentarian, Albert Mayles. There are also a dozen or so behind the scenes clips of the actors at work on the set, along with some interviews. There’s also a fun little faux talk show made by Anderson called The Peter Bradley Show, which highlights miscellaneous people involved with the film like extras, grips, and the late Kumar Pallana, who played Royal’s butler in the movie. Also included in the set are original artwork pieces by Wes Anderson’s cousin and resident company artist, Eric Anderson, whose style perfectly compliments the movie. In fact, the Criterion Collection has used Eric Anderson’s artwork for every one of their Wes Anderson titles, including using some of them as the cover art for each edition, including this one.

So, The Royal Tenenbaums stands as not just an important release for Wes Anderson, but as a groundbreaking movie for their the Criterion brand as well. I’m sure that a lot of people have this film to thank for introducing them to both Criterion and Mr. Anderson. The film has aged very well over the years, though I think that it’s clear that Anderson has clearly moved on to bigger and better movies since then. The Royal Tenenbaums was a launching point for him; an opportunity to show what he can do with more tools at his disposal, and I’m happy that the end result was as successful as it was. My hope is that Wes Anderson continues to stick by Criterion and have every one of his releases available under their label. The one holdout is last year’s Moonrise Kingdom (2012), but I’m sure that a Criterion edition is in the works for it in the near future. The years ahead also looks bright for the director. His next film, The Grand Budapest Hotel is set for release next March and the trailer alone is enough to make me smile. I also like the fact that Wes Anderson’s style has clearly become so identifiable now, that it received a SNL send up this year that was both mocking and reverential at the same time. It even included narration from Alec Baldwin, who was also the narrator in The Royal Tenenbaums, showing just how impactful this film has been. Even if you find Wes Anderson’s style a little too quaint, The Royal Tenenbaums is still worth watching. If anything, this Criterion edition will give this film the stunning presentation that it rightly deserves.