Many animation companies have risen and fallen over the years, but if there is one that has stood tall as the standard, it would be Disney. Disney has continuously put out animated features for nearly 80 years now, and will continue long into the future, and through all that time, it has grown stronger despite facing respectable competition at times. One of the reasons it has remained at the top is because Disney has been the one that has more or less charted the direction of the industry. Whenever Disney touches upon a big hit, it will have ripple effects across the industry as all the other studios try to follow their lead. For instance, when Disney animated musicals based on fairy tales started becoming popular again in the 90’s with films like Beauty and the Beast (1991), it spawned a bunch of similar movies from rival studios trying to capitalize on the same success, like The Swan Princess (1994) and Anastasia (1997). That’s not to say that Disney has always remained ahead all the time. Sometimes a string of failures would catch up to them, or a change in the market leading to tougher competition. Pixar Animation, more than any other, has had the same kind of effect on the industry, being the trend-setter and innovator, and it was very smart of Disney to partner up with them when they did; otherwise Disney’s days at the top would’ve ended. But, even with these two dominant brands leading much of the animation market, it doesn’t mean that none of the other animation studios have put out an inferior product. In fact, some of their movies are just as good as anything by Disney and Pixar. In this article, I will list what I think are the 10 best animated movies not made by Disney or Pixar, because honestly if I had to make a list of the greatest animated movies of all time, those two would dominate. The reason I want to highlight the other studios here is to show the incredible diversity that you’ll find in animation, both today and from the past. So, let’s begin.

10.

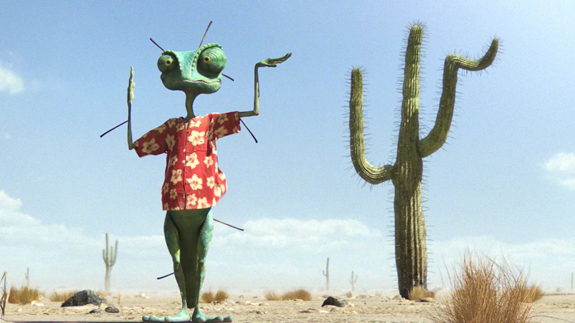

RANGO (2011)

Directed by Gore Verbinski

Not many people knew what to make of this film when they first saw it advertised. The visual designs were bizarre, as were the characters, and the main protagonist was a squeaky voiced lizard wearing a Hawaiian shirt. But, when the movie was released in the spring of 2011, audiences and critics were surprised to find that this Nickelodeon made film was actually a lot of fun to watch. The voice cast, led by Johnny Depp as the titular lizard, was top notch. The visuals were imaginative and well-executed. But, more importantly, it was also hilariously written. What I took away most from this film was the brilliant way that it parodied the Western genre, right down to the smallest details. The design of the western village, made from scrap pieces of junk found by the critters that inhabit the town, is clever, as is a hilarious Apocalypse Now reference when the townspeople try to escape from a mole colony. It’s all hilarious, beautifully animated and it even functions as a true Western. In fact this works better as a Gore Verbinski directed Western starring Johnny Depp than The Lone Ranger (2013) did. Verbinski spent years in visual effects before becoming a director, so this movie really shows him in a creative comfort zone; free to make whatever he wanted. What this movie does perfectly is to not waste it’s premise (basically a spaghetti Western with critters) and bring it to it’s full potential. The best I can say about it is that it doesn’t resemble any other animated film that I know of, and still feels familiar enough to understand. It’s refreshingly original and shows that not every animated film needs to stick close to a standardized formula.

9.

THE TRIPLETS OF BELLEVILLE (2003)

Directed by Sylvain Chomet

Europe has a long history of crafting beautiful animated features themselves. Whether it be English made films like Watership Down (1978) or Yellow Submarine (1968) or the French made sci-fi classic Fantastic Planet (1973), animation is a proud art-form found all across the continent. The finest example of European animation in my opinion would be this fairly recent film from French animator Sylvain Chomet. His style is unlike anything else I’ve seen in animation and it gives the world of this movie a unique identity. The movie follows an elderly old woman with a club foot as she crosses the ocean in search of her kidnapped grandson, who’s also a Tour de France cyclist. On her journey, she reaches the city of Belleville where she befriends the titular triplets (a long retired night club act) who agree to help her out. The movie is told with minimal dialogue and it’s amazing how well Chomet is able to tell his story purely with visuals. And those visuals are amazing. Every frame of this hand drawn masterpiece is stunning and finely detailed. Not only that, but the characters are wonderfully realized (visually and narratively) and the humor is charmingly twisted as well. Keep an eye out for a small little mechanic character who bears a close resemblance to another famed animator. Suffice to say, this is a very French movie, complete with characters dining on frog legs. But, that’s also part of the joke too. Chomet’s designs really stand out as being stylistically unique; and very non Disney. If you haven’t checked this one out before, please do so. It may not be what you’re used to, but then again, it’s very much worth taking in some international flavor when watching some quality animation.

8.

PARANORMAN (2012)

Directed by Chris Butler and Sam Fell

Stop motion animation has been a popular medium for many decades, but it wasn’t until 1993’s The Nightmare Before Christmas that a full length feature was made utilizing the technique. Since then, plenty of other stop motion animated films have been released. I could have easily included something from Aardman Animation on this list, like Chicken Run (2000) given the UK-based studio’s high regard in the industry. But, for what I consider to be the best film to come from the medium, I would have to say it’s this film from the Portland, Oregon-based Laika Studios. Laika made a splash right away in it’s still young history with the critically acclaimed Coraline (2009). But, it was with their follow-up ParaNorman that they really showed off what their capable of. ParaNorman is a spectacular animated film, featuring a surprisingly mature story about social acceptance and over-coming prejudice. It’s also got plenty of self-aware humor to it as well, poking fun at horror movie cliches. The animation is also astounding. The 3-D printed models used for the characters are a far cry from the clay-molded ones of yesteryear, with incredible life-like detail to them. It’s hard to believe sometimes that you are watching something crafted and animated by hand rather than with computers. Like Disney and Pixar, Laika is taking it’s art-form to the next level and leading the medium forward, and it’s doing so on it’s own terms. With a well-rounded story and stunning animation, ParaNorman showcases what stop motion is capable of more than any other feature in it’s class to date.

7.

SOUTH PARK: BIGGER, LONGER, AND UNCUT (1999)

Directed by Trey Parker and Matt Stone

South Park isn’t the only animated TV series to spawn it’s own film. The Simpsons finally got their own movie in 2007, and there have also been films based on Spongebob Squarepants (2004), Powerpuff Girls (2002), and even with classics like The Flintstones (1994) and The Jetsons (1990). But, what is interesting about the South Park movie is that it made it’s way to theaters very early in the show’s run. This was released in the middle of the show’s third season and today the series is still on the air getting ready for season number 20 this fall. During all that time, the show has evolved and matured, and yet, the movie still holds up well. The fact that it’s uncensored as opposed to the show makes this an especially fun movie to watch, because it shows the duo of Parker and Stone at their most irreverent. Like all the best satires, the movie takes aim at everybody; whether it be Canadians, overly-sensitive parents, political leaders, religion; even Gandhi isn’t spared. And it’s all laugh out loud funny. What also makes this movie memorable is it’s musical score; mocking the Disney musical cliches while at the same time standing on it’s own lyrically. The movie was even nominated for an Oscar for the song “Blame Canada,” although the musical highlight for me is still the hilariously obscene “Uncle F***a.” I also get a kick out of the show’s depiction of Saddam Hussein, who it turns out is in a homosexual relationship with Satan here. The way the character is animated, with a Photoshop cut-out of the real-life dictator’s head, and the high-pitched voice that they chose to give him are both silly to perfection. All the show’s characters transition well to the big screen, especially the foul-mouthed Cartman, who gets much more free reign here to say whatever he wants. It’s a perfect translation of a still legendary series that took full advantage of the creative freedom of the cinematic experience.

6.

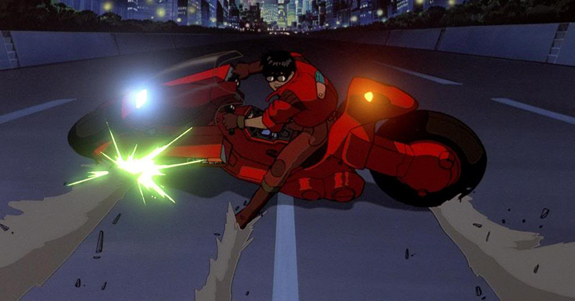

AKIRA (1988)

Directed by Katsuhiro Otomo

Of course, you can’t look at the whole of animation history without taking note of the world of Anime, imported over from Japan. Japanese animation is unlike anything else that we see in the genre; using limited character animation in conjunction with highly artistic and sometimes stylized background art. There are many different types of anime out there, from really cartoonish to hyper-naturalistic, but despite all this diversity, Anime still has a distinctive look that characterizes it. One of the first Anime films to really grab a hold of Western audiences was this punk-infused dystopian masterpiece, Akira. At a time when Disney was getting back into the groove of making colorful fairy tales once again, Akira was wowing audiences with it’s dark atmosphere, it’s sometimes shocking use of violence, and it’s jaw-droppingly beautiful animation. It was also grand in scale, at a time when few other animated features were allowed to be, even at Disney. Akira follows a group of biker gang members who get caught up in a conspiracy involving genetic mutation and children with extraordinary psychic powers. When one of these children named Tetsuo begins to run amok, it’s up to his friend Kaneda to try to stop him, before he loses control and destroys the city. The near-distant future-scape is stunningly realized, but not overdone. It appears that director Otomo draws just as much inspiration from action movies from that time period as he does from other animated films, and it’s a combination that works really well. Akira is considered one of the most important and influential Anime films of all time, and it’s a distinction that’s well deserved.

5.

THE LEGO MOVIE (2014)

Directed by Christopher Miller and Phil Lord

One of the most unexpected animated classics to come out in the last few years, period. I’m sure that none of us ever expected The Lego Movie to be as good as it ended up being. When originally announced, I’m sure that most of us thought that this was just going to be a crass commercial exercise in order to sell the public into buying more LEGO sets. But what we ended up getting was much more than that. It was a brilliantly crafted comedy full of so many sight gags and in-jokes that it’s hard to count. It really is a movie that has everything we could want in a feature. The duo of Miller and Lord have also been responsible for the 21 Jump Street (2012) movies, which also ended up being much smarter and funnier than people had expected. All the pop culture references are hilariously executed, but the jokes also work because effort is put into the central story. The film’s main protagonist, Emmett, really helps to ground the film and make it work, and he’s portrayed with a lot of heart by actor Chris Pratt. Other new characters like Vitruvius (Morgan Freeman), Wyldstyle (Elizabeth Banks), and Good Cop/ Bad Cop (a hilarious Liam Neeson) are also great in the film. But, what also makes this movie stand out is the amazing animation. The film is CGI, but it’s animated to look almost like stop motion, making the whole LEGO world appear as if it was hand-crafted. It’s visually amazing to watch, especially when the finished result looks like real LEGOS, right down to the smallest detail. By being both stunningly animated and laugh-out-loud hilarious, The Lego Movie has become an instant masterpiece. And, it also gives Batman his own song, which is just awesome.

4.

THE SECRET OF NIMH (1982)

Directed by Don Bluth

During the years following the sudden passing of Walt Disney, the Disney company found itself stuck in a mire of self-doubt and lack of direction. No one in the animation department knew what to do without Mr. Disney at the helm, so for several years they just resorted to coasting on formula rather than making breakthroughs in their medium. This naturally led some of the animators working for Disney to become frustrated with the direction of the company, and one of those animators was Don Bluth. Bluth famously parted ways from Disney and set out to create his own, independent animation studio to directly challenge the stranglehold that Disney had over the industry. His goal was to make riskier and more mature animated features that would help elevate the animated medium over the “kid-friendly” stuff that Disney was making. And over the next decade, Bluth indeed created a stellar body of work, including An American Tail (1986), The Land Before Time (1988), and All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989). Though all his movies for the most part took risks and refrained from falling into formula (at least at first), no movie better illustrated his mission statement than his first feature, The Secret of NIMH (1982). NIMH is a remarkably assured and gripping animated feature, different from Disney in every way, and yet animated to a level on par with Disney at it’s best. Following the trials of farm mouse Mrs. Brisby, the movie is harrowing and unforgettable; and even not afraid to be a little violent at times, without sensationalizing it. Bluth’s latter films like Rock a Doodle (1993), Thumbelina (1995), and Anastasia (1997) would fall into a formulaic hole later on, but The Secret of NIMH was at least a much needed shot in the arm for animation in it’s time, and gave an animator who had something to say his due respect.

3.

HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON (2010)

Directed by Chris Sanders and Dean DeBlois

For the last decade or so, the animation industry has been defined by one primary rivalry, and that’s been Disney vs. Dreamworks. Dreamworks made a splash in the industry with their enormously successful Shrek franchise, and for many years they were also the box office champions in the animation world. The only thing that eluded them though was critical praise, as most of their animated films were viewed more as crowd pleasures that were just okay, rather than all-time masterpieces. Pixar, under the roof of the Disney Company, was instead soaking up all the accolades and awards during this same time. This was until a movie called How to Train Your Dragon was released in 2010. Created by two Disney ex-pats, Chris Sanders and Dean DeBlois, Dragon is just as strong as anything from Disney and Pixar, both visually and with it’s story-telling. The movie is exceptionally well written, relying more heavily on character development than pop culture references and slapstick gags, something that unfortunately characterized a lot of Dreamworks’ earlier films. The animation is also high-caliber, giving Dragons a sense of scale few other animated films ever try for. The central relationship between the protagonist Hiccup (voiced by Jay Baruchel) and his dragon companion Toothless is also the heart and soul that drives the movie; reminiscent of movies like E.T. (1982) or even Lilo & Stitch (2002), which these same directors are also responsible for. This was also the first ever time where I ever felt that Dreamworks actually bested Pixar, with the similarly themed Brave (2012) feeling un-compelling by comparison. Dreamworks’ Dragons deservedly garnered universal praise, and it showed that they were capable of creating more than just commercial entertainment; they could create popular art as well.

2.

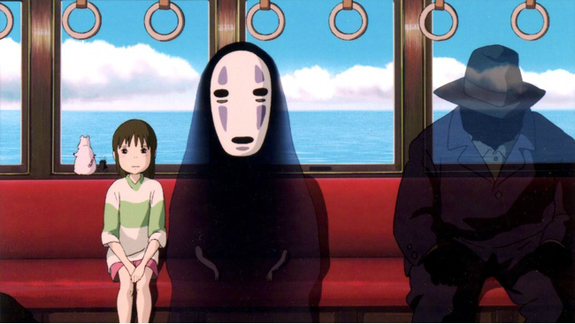

SPIRITED AWAY (2002)

Directed by Hayao Miyazaki

Like I highlighted before with Akira, Japanese anime was and is a medium that’s unafraid to push a few buttons in the world of animation; even going to extremes in terms of depicting violence and sex on screen. But, not all of anime is defined by this. There are other animation studios from Japan that also have made a name for themselves by portraying a more colorful and lighthearted view of the world. This has been the defining characteristic of the acclaimed Studio Ghibli, and also the style of it’s creator, Hayao Miyazaki. Miyazaki is often considered by many to be the Walt Disney of Anime, and it’s not hard to see why. His animation style is very grounded, but also highly imaginative, setting a high standard that the rest of the industry tries hard to emulate, even outside of Japan. Though Miyazaki has created violent films from time to time (Princess Mononoke for example), his films often are more characterized by more innocent, fairy-tale-like stories; not all that dissimilar from Disney. Some of his movies like My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), and Ponyo (2008) are beloved family classics, but what many consider to be the director’s finest work is the Oscar-winning Spirited Away (2002). Spirited Away is without a doubt one of the finest anime films ever made, if not the best. Following the story of a lost girl named Chihiro in a world inhabited by spirits and monsters, every frame of this film is a work of art. The best moment in the film though is the train ride sequence. It’s a quiet, reflective moment that you rarely see done in an animated feature and it shows the confidence that Miyazaki has in the art-form, showing that even animation can have a contemplative side to it. It’s moments like this that make Spirited Away a masterpiece and Miyazaki one of the industry’s greatest artists.

1.

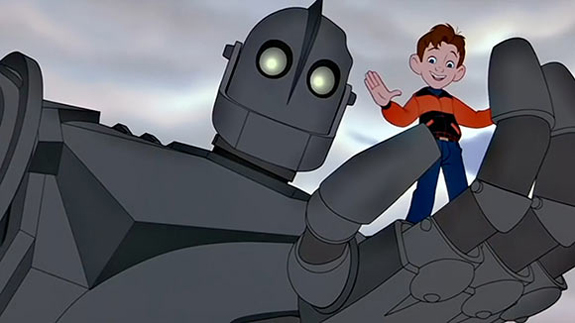

THE IRON GIANT (1999)

Directed by Brad Bird

If I had to choose any animated film that would stand on the same level as anything from Disney and Pixar, it would be this Brad Bird directed masterpiece. Made by the short-lived Warner Brothers feature animation studio, The Iron Giant is a movie that gets everything right; from the high-quality animation, to the voice casting, to the unforgettable coming-of-age storyline about the bond between a young boy named Hogarth and his 100 foot tall robot friend. Though it was a flop when it first premiered, the movie has steadily been rediscovered and is now universally beloved. Not only does it represent the best that animation can do today, but I would dare say that this film is exactly what Walt Disney would’ve made in his time, or at least would’ve approved of. And that’s probably the kind of result that Brad Bird was aiming for. He was trained in art school by some of Walt Disney’s own top artists, so really The Iron Giant is a manifestation of the lessons he took to heart during his education. Of all the films on this list, this movie shows the greatest representation of a Disney style film made outside of the influence of the Disney company. The characters are especially what makes this a standout; never once falling into archetypal caricatures and instead feeling like fully fleshed-out individuals. The depictions of Hogarth and the Giant are especially effective, and whoever could’ve predicted that Vin Diesel of all people could touch so many hearts as the voice of the Iron Giant. If you don’t feel anything the moment when the Giant says “Superman” as he saves the day, then you my friend are made of stone. Brad Bird eventually became part of Disney company later, making hits like The Incredibles (2004) and Ratatouille (2007), but his only feature outside of the House of Mouse is still what I think is his best work, and absolutely one of the greatest animated features ever made.

I’m sure that after reading this that some of you will probably complain over some omissions, and I certainly understand that. There are so many good animated features made outside of the long reach of Disney, and more are created every day. These are what I believe to be the best of that crowd, and it’s based not just on how good they are, but also by what they represent. For the most part, these movies represent different animators or animation studios finding an identity that’s all their own that can stand the test of time. One of the big problems in the world of animation is a lack of identity, instead choosing to just look at what Disney is doing right at the time and just copying their formula. Copycat movies are an unfortunate result in the animation industry, but the good thing is that audiences have discerning tastes in the market as well, and they resoundingly reject animated films that choose to be unoriginal and lazy. Overall, we need a big studio like Disney to set the standard for the industry, because their success pushes all competitors to up their game in order to compete. And if there is anything to understand from a list like this is that the best animated features are the ones that rise to the challenge. In some cases, like with How to Train Your Dragon and The Iron Giant, we’ve seen strong cases for animated films that may have actually bested the powerhouses of Disney and Pixar at their own game. Animation is a great art-form, and made better still when everyone involved works toward making a better product overall.