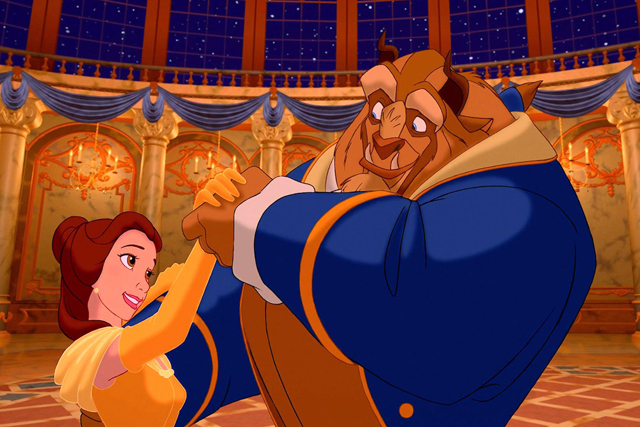

Going all the way back to Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937), Disney has built a long canonical line of feature films that have been the backbone of their company. Even to today, the animated film canon is central to Disney’s identity, and they have been keeping track of their total number of features for the sake of celebrating every milestone. Here, in 2021, they have reached yet another of those, with their 60th overall animated feature. This particular milestone is special in how it represents the amount of success that Disney has had in recent decades. It took Disney 54 years to reach their 30th feature film (1991’s Beauty and the Beast) and only 30 years to reach their 60th; the newly released Encanto. That accelerated pace shows just how prolific Disney has been in recent years, being propelled by the Disney Renaissance and extending now through the Digital Era. It has been a very transitional time period for Disney animation, but of course, there is plenty more planned for the future. Though Encanto has been planned for some time to hold up the mantle of the 60th Disney feature, it became speculative for a time if it may indeed be a theatrical release. The 59th feature (Raya and the Last Dragon) had to settle with a hybrid theatrical and digital release last Spring, which in some ways took the wind out of it’s sales and diminished it’s ultimate box office take. Of course, it’s the best they could do for audiences at the time because of the lingering effects of the pandemic, and Disney not wanting to stall the release any longer. Still, depending on how things panned out, the hybrid model could have ended up becoming the new norm, or even more dire for the theatrical loving community, it would show that digital only was the preferable choice. As the pandemic lingered on through the summer, Disney wasn’t really confident either way. And then the unlikely blockbuster success of Marvel’s Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings resurrected the sleepy theatrical market and helped to confirm for Disney that theatrical first was the way to go. Thus all of Disney’s remaining 2021 releases would be premiere first in theaters.

Unfortunately, through this era of pandemic related experimentation, Disney revealed itself to be playing favorites a bit with their catalog of titles. Of the movies that did get a theatrical release instead of only digital, the Disney Animation department seemed to benefit the most, while Pixar was left off the movie screens altogether. Pixar’s last two animated features, 2020’s Soul and 2021’s Luca both were dropped onto Disney+ instead of theaters. It’s understandable for the movie Soul as it was premiering during the pandemic’s peak, but Luca premiered in the summer, long after movie theaters across the country had reopened and Disney had successfully implemented their hybrid release on films like Raya and the Last Dragon and Cruella (2021). Why Luca was chosen just for digital doesn’t make much sense out of that. Pixar is still a valuable and profitable brand, and the movie had a lot of broad appeal across all ages. From the outside, it appears that Disney was playing favorites with their own in-house animation studio, hoping to use them to drive the return to theatrical. Then again, Disney may have been more guarded with regards to their Pixar titles, believing that a digital release would help them avoid disappointing box office in a still unsettled market and possibly believing that the movie would find more eyes on Disney+. What ever went on behind the scenes, it’s unfortunate that Pixar got the worst situation out of the lingering effects of the pandemic, while Disney Animation got both of their 2021 releases the theatrical releases they deserved. Personally, I am biased, and I wanted all movies to make it to the big screen in any way they could. Disney made their choice based on how they saw things, and sadly that meant that most audiences couldn’t see Luca the way it was intended to be seen. 2022 will be different, as Pixar has two films set for theatrical first releases (Turning Red and Lightyear), and Disney has no doubt has sided with theatrical for the long run, though any further economic disruptions could change things. For now, we are given the new theatrical film, Encanto, Disney’s milestone 60th feature. The question is, does it have the same kind of Disney magic as all of it’s predecessors, or did it waste it’s good fortune of a milestone release?

Encanto is set in an unnamed fictional land based largely on Columbian culture. After escaping vicious marauders who have driven them from their homes, a family makes their way into the unknown terrains of the South American jungles. After loosing her husband who sacrifices his life to buy them time to escape, Alma Madrigal (Maria Cecilia Botero) and her newborn triplets are left alone in the wild. Miraculously, the candle that had lit their way through the dark becomes enchanted. The candle creates a home around them to give them shelter, which itself comes alive. Several years later, the Madrigal home has become a paradise and safe haven, with many other peaceful settlers creating a village around the house. The triplets have grown up and as we learn, have all been given special gifts from the house that involve supernatural powers. The eldest daughter Julieta (Angie Cepeda) has the ability to heal people with the food she cooks. Pepa (Carolina Gaitan), the younger sister, can control the weather. Pepa’s older children Dolores (Adassa) and Camillo (Rhenzy Feliz) have the gift of enhanced hearing and shape shifting respectively. Julieta’s three daughters, Luisa (Jessica Darrow), Isabela (Dianne Guerrero) and Mirabel (Stephanie Beatriz) also live in the home with the rest of the family. Luisa and Isabela have their gifts, which are super strength and conjuring flowers in her wake respectively, but Mirabel stands out because unlike the others, she was not given a gift. When the family gathers the town to celebrate the gift giving to Pepa’s youngest son, Antonio (Ravi-Cabot Conyers), who ends up talking to animals, Mirabel discovers something wrong with the house. She believes that the house is beginning to crumble and the magic begins disappearing with it. She intends to discover for herself what is happening. The clue to the house’s fate lies in what remains of her Uncle Bruno’s room. Uncle Bruno (John Leguizamo) left the house long ago after he discovered through his power of seeing the future that the thing Mirabel is fearing will come true, and the family has since never spoken of it. But, Mirabel is set in finding out the truth behind Uncle Bruno’s prophecy and discover why she is at the center of it.

Encanto marks the second collaboration between Disney Animation and famed songwriter Lin-Manuel Miranda. His first project with them was the hit film Moana (2016). Encanto hits a little closer to home for Miranda who gets to tap more into his Latino roots for the music in this film. This also finds him a lot more involved in the production, because he’s also credited as part of the story team on this film. This movie does indeed feel more crafted around Miranda’s contributions than anything else he has done with Disney, with the songs definitely showing his distinctive writing style. This is both a good thing and a bad thing. For one thing, the songs are definitely well crafted and catchy. On the other hand, it almost feels like more focus was given to the songs than anything else in the movie. Encanto is unfortunately a very unfocused movie that feels too lightweight to leave an impact. I was hoping for a more rousing adventure from the likes of Disney, but the movie keeps things very low stakes throughout. The Madrigal home is central to pretty much every aspect of this movie, and the film doesn’t even venture outside of it that much. As a result, the movie just comes across as being very small, which is a little bit disappointing. For a studio that once had climaxes that involved fighting dragons, or battling on the highest points of a mighty palace, or chasing after one’s true love and possibly laying their life on the line to save them, this movie’s climax hinges on a simple generational disagreement. I see how it fits within the story thematically, but it’s still kind of anti-climatic. The movie, as I mentioned before is best served by Lin-Manuel’s involvement, as his songs are where the movie comes alive the most. But, in between the songs, there isn’t much story to speak of. It’s just a simple series of events between a single family, dealing with their own internal dramas, with the only twist being that they mostly all have special powers. And those powers are really explored as much as they should be. It just feels like the powers are there to liven up the story and give the animators something to have fun with.

Moving from that, the movie is not an absolute failure in story. It certainly is a lot better than Frozen II (2019). The Lin-Manuel Miranda songs are definitely what salvages the movie for the most part. If you are familiar with Miranda’s style, which extends from his movie contributions like this and Moana, as well as his most iconic work, the Broadway show Hamilton, then these songs will feel very familiar as well. Miranda’s hip hop infused lyrics manage to work seamlessly with the Latin beats of the main score. I often found myself marveling how the singers in the film manage to string together so many words in a single breath. The songs are their own special achievement in this movie, and I’m sure that many people will find themselves humming these tunes afterwards, and replaying them on Spotify when they get home. They may not have the sing-a-long re-playability as some of Disney’s most long lasting hit tunes like “Be Our Guests,” “Under the Sea” or “Hakuna Matata,” but no one is going to come away feeling disappointed by these songs, even if they like me find the story itself to be disappointed. The animation in the movie also comes alive and rises to the challenge of these songs. Directors Jared Bush and Byron Howard (Zootopia) certainly bring a playfulness to the songs, whether it’s through the creative staging or the wild character animation. I think one of the highlights is a catchy number called “We Don’t Talk about Bruno,” a song going into the backstory of the character, which definitely felt like all the departments working to their fullest, from the vocal performances, to Lin-Manuel’s manic songwriting, to the clever creative animation, all put into this tango like showstopper. Most of the other songs do their job well enough too. I think that the reason why the movie may have faltered a bit in the story department is because the songs probably came first and then the story was crafted to surround them, which wasn’t as assembled with quite the same amount of care or energy.

The movie does benefit from an effective main character as well. I like the fact that out of this family of super human beings, the movie’s plot does hinge on the two characters who don’t have any gifts; Mirabel and her Abuela Alma. The fact that the main character has to work at a disadvantage that her extended family does not have helps to make her role in the story more interesting. She was denied something that everyone else that she loves managed to gain, and she doesn’t understand why. It makes her character motivations clear. I like the fact that she is neither portrayed as purely good or distantly resentful. She bounces back and forth between wanting to know why she was left out and having it not be the worst thing in the world for her. It makes her more dynamic as a result, as you see the internal conflict in her guiding her through the mystery that she must unfold. The rest of the family are a colorful bunch of characters as well, though I feel like some of them could have done with a bit more personality other than the powers that they show off. The supporting characters that stand out the most are those in her immediate family. Her sisters, Isabela and Luisa, in fact are the only other characters in the movie who get their own songs. Luisa’s song “Surface Pressure” is another highlight, especially in the way it stages the song around her super strength ability. It might have served the movie better if it trimmed the more extended family members and just focused on a more tightly knit family unit. Not that the other characters are bad in any way, it’s just that the movie has a hard time giving all of them any amount of spotlight. One really welcome character is Uncle Bruno, who comes into the story fairly late. Though he has limited screen time, he does make the most of it, with John Leguizamo delivering a delightfully eccentric vocal performance. Stephanie Beatriz also is strong as Mirabel, making her both funny but not obnoxiously quirky. Given her already long working history with Lin-Manuel Miranda in projects like In the Heights (2021), she is clearly skilled enough as an actress and singer to take on a character like Mirabel.

Where the movie also delivers up to the high Disney standards is in the animation. This is a visually impressive film, with animation up to the same quality of some of Disney’s most classic titles as of late. One thing that I especially was impressed with was the visualization of the Madrigal house itself. The house is a world in of itself, quite literally in fact, as the individual rooms for the family members open up into large spaces, like the Tardis from Doctor Who. One of the nicest touches is that the movie turns the Madrigal house into a character itself. The house comes alive with the floors, drawers, doors, shutters and tile roofs all moving independently and giving assistance to the characters. It’s a home with a personality, and some of the biggest laughs in the movie comes from the clever ways that the animators found to communicate gestures through the architecture of the house. The movie also has a colorful palette to it. The colors pop on screen and dazzle with a wide kaleidoscope of visual splendor. You also really get the sense of the Columbian influence of this movie, where the multicolor house stands out from the deep greens of the dense jungle that surrounds it. I’m sure the team of animators on this film looked at how small Columbian villages come to life through their choices of color in contrast with the tropical surroundings. It wouldn’t surprise me if they had come across quite a few buildings that looked like the Madrigal home in their research. The movie benefits a lot from the work put it in it’s setting, but it also makes the magical gifts given to the family interesting as well. I especially like the ideas of Pepa’s weather control being limited to a cloud flying over her head and raining entirely around her depending on her mood. Isabela’s flower power is also beautifully realized. Overall, while the story may be lacking, the animation is undoubtedly on par with Disney at it’s best, and in many ways also offers up a few worthwhile surprises that helps to set this movie apart within the canon.

Encanto is by no means a bad film and in many ways I think it will prove to be a hit with audiences. It might just be my sometimes impossibly high standards with regards to Disney animation, but Encanto just felt like it lacked that special thing to put it higher on the list of great Disney film. I want a Disney movie that has a lot more to say like Zootopia, or comes to a much more exciting climax like Aladdin (1992). Encanto just feels like an exercise for the animators and less like a bold statement for the future of animation. Perhaps where some of my disappointment comes from is the fact that this is a milestone film and that it generally feels a bit too small for that distinction. All that said, there is still a lot to like with this movie. The characters are likeable, the Lin-Manuel Miranda songs are catchy, and the animation is definitely top notch. It’s just all put together in a way that felt like it wasn’t reaching it’s full potential. For a milestone movie, I really think something more ambitious like Raya and the Last Dragon should have been given the pivotal milestone. But, that’s just my opinion. I’m sure Disney believed in this movie more and were happy to spotlight it. It certainly shows that they are eager to continue working closely with Lin-Manuel Miranda. Whether or not he continues to work with Disney more is uncertain, but this movie will likely be a good collaboration that both sides will be proud of. Regardless of what I personally thought of Encanto, it is great to see Disney Animation reach this amazing milestone, and even more importantly, do so in the theatrical market. I can definitely say that this is a movie that benefits from being shown on a big screen, and I’m sure that audiences will appreciate having that option available to them. It is not an all time great, but Encanto is a perfectly fine piece of entertainment that will no doubt leave audiences happy and feeling as magical as the enchanted world they have been welcomed into.

Rating: 7/10