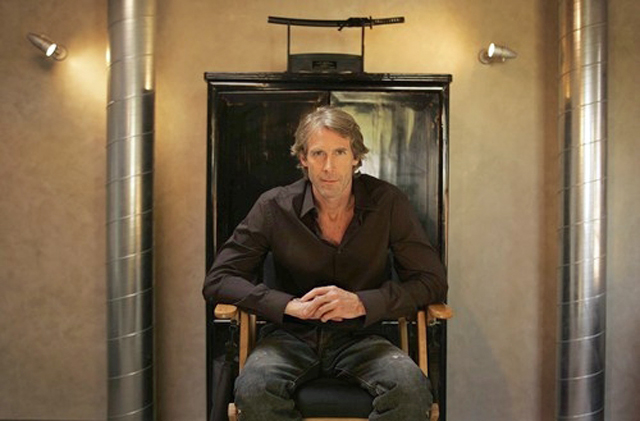

For the first couple entries in this series, I spotlighted filmmakers who are universally praised as among the best to ever step behind the camera. Now, let’s take a look at a filmmaker with a somewhat different reputation in Hollywood. Director Michael Bay is, putting it lightly, a divisive filmmaker. On the one hand, he’s prolific, efficient, and has a distinctive style that sets him apart in the field. On the other hand, he’s also brash, a show-off, and indulgent to the point of inanity. Oftentimes, he’s labeled as the poster child for what is wrong with Hollywood, with his movies often being panned by critics for the crime of being overstuffed with Bay’s own unrestrained style. But, at the same time, Michael Bay can’t just be dismissed as just another bad director. The truth is, he does have talent as a filmmaker; it’s just not always focused on the right things. He does know how to create eye-catching images, utilize complex on set special effects to spectacular effect, and more remarkably he manages to keep his movies under budget and on schedule. That last aspect is probably what has kept him in good standing within the industry, because they know that he can deliver a product without worry. And his films for the most part continue to reach an audience, even if they do appeal to some of humanity’s lowest cultural aspects. His indulgences prove to be a blessing and a curse, as they allow his films to stand out, but also spotlight his sometimes not too appealing personal tastes. All of this makes him a fascinating individual overall, and as a filmmaker, it’s interesting in seeing how his career defines the distinctive line between those who are storytellers and those who just make movies.

Bay himself is an interesting case of how Hollywood grooms talent over time. After earning his degree in film-making from Wesleyan University, Bay made a quick rise within the industry, cutting his teeth on commercials and music videos. His “Got Milk?” ads in particular launched him to national attention, which eventually led him to being assigned to direct a Will Smith vehicle called Bad Boys (1994). From their, he made a steady stream of blockbuster hits including The Rock (1996), Armageddon (1998), and the sequel Bad Boys II (2003). He also was assigned by Disney to helm their Titanic (1997) copycat Pearl Harbor (2001), which itself was deemed an indulgent failure. But, it wouldn’t be until he teamed up with producer Steven Spielberg that he would find the production that would ultimately define his career in a nutshell. That project was Transformers (2007), a movie that showcases all the good and bad aspects of Michael Bay as a director. It’s a well constructed, but emotionally hollow and obnoxiously indulgent film, that mirrors exactly the kind of person that we imagine Michael Bay to be, and sometimes are confirmed as much by his own actions. Essentially, what we see in Michael Bay is someone that has been shaped by the industry, instead of himself shaping it. He has become a workman who fulfills the obligations that are placed in front of him, but never once pushes to do anything beyond that. And the sad truth is that because of this, he has limited himself as a storyteller. One wonders what kind of filmmaker he might have been had he not skyrocketed so quickly, and had been trying to hone his skills for years in order to gain notoriety. It might of meant he would have taken far more risks over the years, instead of just returning to that Transformers well again and again. In this article, I’ll be looking at the different aspects that define Michael Bay the filmmaker, and see how they represent the good and the bad throughout his career.

1.

“BAYHEM”

If there is one thing defines Michael Bay as a director, it’s his very clear love for mayhem on screen. Whether it is overblown pyrotechnics, or whiplash quick editing, or CGI enhanced screen filler, he definitely tries to fill every frame of his movie with activity. This use of cinematic overkill has even been given it’s own term called “Bayhem,” owing it’s namesake to him specifically. While Bayhem does illustrate the directors prowess on a technical level, it is often the thing that many people also hate about him as a filmmaker. It may seem like so much activity on the screen helps to give the movie more epic weight, but oftentimes, it purely just numbs the audience down when it’s done way too much. It’s cool seeing an explosion happen for the first time, but when it’s the ten one you’ve seen in a row in one action sequence, then it just doesn’t feel special anymore. Truth be told, nobody films an explosion better than Michael Bay. Utilizing multiple camera set ups and a variety of tricks like slow motion, he can turn what was a quick explosion on the set and make it feel much bigger on screen. Some spectacular instances of this include actual pyro blasts set off on real WWII era warships in Pearl Harbor, as well as the desert fight out in Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (2009). But, again, after you see one, you’ve seen them all, and too many in one film diminishes the returns over time. The unfortunate result of Bay’s success, is that other filmmakers mistakenly believe that more “Bayhem” is exactly what their movies need too. You see this in Transformer clones like Battleship (2012) and series reboots like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (2014) and Power Rangers (2017). The problem is that no amount of onscreen eye candy can fix a hollow story-line, and Bay’s problem is that he often puts visuals ahead of narrative. It’s overall a mistaken belief that a static screen creates a boring scene, and that more thing going on within the frame will correct that.

2.

AMERICA

Every filmmaker has certain motifs that they like to return to over and over again, and Bay has his own as well. If there is something that you can easily spot consistently throughout his movies, it’s the use of American iconography. Bay steeps his films in heavy patriotic fervor, so much so that his movies are often criticized as being too “flag-waving” and sometimes even propaganda. It’s not a bad thing necessarily to showcase the country you’re from in the best possible light; that’s his prerogative as a filmmaker. But, again, like his use of cinematic mayhem, too much use of it eventually makes it feel hollow by the end. Bay’s films are often carry over the patriotism further than what’s in the movie. The American flag has been used several time as a background for the advertising of his movies, including the less reverential Pain & Gain (2013). The only other filmmaker who uses the flag as much is Oliver Stone, but his intentions with the American flag are often meant to be ironic. Still, Bay makes American iconography stand out in his movies, not just with the red, white, and blue, but also with it’s landscapes and landmarks. He even set a whole movie within a famous American landmark with the Alcatraz set The Rock. Perhaps Pearl Harbor demonstrates his Americana motif more than any other film, as it portrays everything about the places and people of it’s setting in a larger than life way. The movie also demonstrates the very cozy relationship that Bay has with the armed services of the United States. In exchange for a positive portrayal of the American military apparatus, Bay gets special access to film his movies with authentic military equipment and on location on their bases as well. Some would say that makes Bay a propagandist, but at the same time, Bay is not deceitful in this aspect either. He respects military men and women and tries to give them as heroic a portrayal as he possibly can. One can’t fault his attraction to this motif, just the effectiveness that he utilizes it.

3.

MAGIC HOUR

If there is something that I can definitely praise Michael Bay for as a filmmaker, it’s his expert use of ‘magic hour” in his films, and his almost obsessive devotion to it. For those who don’t know what “magic hour” is, it is the brief late afternoon span between say 5 and 7 pm when the lighting of the sun is just right to give a filmed image a distinctive, cinematic glow. If a film is shot any earlier than than, like at “high noon” when the sun is at it’s brightest, everything will appear too washed out. Michael Bay’s style has become unique in the industry because of how well he uses this “magic hour” to effect in his movies. In fact, if you look at his entire filmography, you can easily see that the majority of his scenes are filmed in the “magic hour.” Even morning scenes appear like they were shot in the late afternoon, just to give the movie the consistent look that Michael Bay desires. And, for the most part, it works very well. In the magic hour, Bay manages to balance light and dark in a more appealing way than it normally would if he shot the scene fully lit. It also gives his movies a distinct feeling of atmosphere that also elevates the viewing experience. In movies like Bad Boys, The Rock, and a few of the Transformers, he often uses “magic hour” as a way of conveying warm temperature, steaming up a scene to give his characters that extra element to work with. It also gives Bay’s films an interesting hue of color that makes them feel distinct; not over-saturated with extreme high contrasted, but not washed out and pale either. The only time I see the technique not used is in the night time scenes, which themselves are lit in a way that blends together with the “magic hour” moments. So, despite Bay’s more unfortunate directorial choices, this is one that has actually benefited him as a filmmaker, and I hope that it’s a discipline that can extend to improve his other techniques.

4.

CGI… LOTS OF IT

One of the negative aspects of Michael Bay’s post-Transformers career trajectory is that it has made him far more reliant on CGI than he ever was before. One wishes he would show more restraint and try more in camera effects like he had earlier in his career, because those scenes at least play to his strength as an expert in shooting pyrotechnics. But, with Transformers, he began to look at CGI enhancement as a way of eliminating the middle man and giving his movies epic scale without ever having to set up the shot the normal way. The unfortunate problem with this is that Michael Bay can’t compose a CGI template shot the same way that he can a practical effect. He likes to move the camera around too much, and that impacts the way that we experience the CGI effect on screen. Too often now we see his movies putting a lot of CGI activity on the screen without it ever leaving an impact on us. The frantic camera movements combined with the overly animated effects also spotlight just how unreal the effects look as well. You can tell that a lot of work went into creating the models of Optimus Prime and Bumblebee, but we are never able to get a satisfyingly close look to appreciate them. And Bay’s continued insistence on using CGI more in his movies often has the end result of looking cool, but never actually feeling cool. This problem stems as far back as Armageddon, which itself suffered from too high a reliance on CGI effects. Oftentimes, you couldn’t tell what was going on in a scene, especially when the characters are on the asteroid itself, because Bay never stops to let us appreciate the work. My guess is that Bay is continually fascinated by the limitless potential of computer enhanced imagery, but he’s never picked up on learning the subtle applications that can make it work better. Like everything else in his movies, it’s more mayhem masquerading as art.

5.

SELF-INDULGENT CHARACTERS

One other major complaint that Michael Bay has faced with every film is his serious lack of appealing characters. In many ways, Bay likes to imagine every character in his films as an extension of himself. They are often eccentric, cocky, have an air of superiority despite never earning it, a bit nerdy, and very self-involved. Not all of Bay’s characters are unappealing though. I found myself very much enjoying the quirkiness of Nicholas Cage’s Stanley Goodspeed and the cockiness of Sean Connery’s Mason in The Rock, and the trio of Mark Wahlberg, Dwayne Johnson, and Anthony Mackie in Pain & Gain also proved to be a winning combination of Bay “bros.” But, his style of characterizations only work when there is some other factor to balance them, like a more natural performance from a co-star or a supporting player. But, when every character in the movie is cocky and brash, and very, very Bay-ish, then the movie suffers. This is the big problem with the Transformers movies, because every character is an archetype, or even worse, a stereotype, which only makes them annoying and not redeeming. The character of Sam Witwicky (played by Shia LaBeouf) may in fact be one of the least appealing characters ever committed to cinema, purely because both Bay and LaBeouf mistakenly thought that defining his character as this cocky, self-absorbed nerd would actually click with audiences. It’s a bad sign when your main character is so unlikable that he’s completely written out of the series with no explanation. Unfortunately, Witwicky is only one of a wide range of poor character choices on Bay’s part. There has to be a balance of diverse personalities to make your cast of characters appeal to all audiences, but when you fall in love with only one type of personality (even worse, one that mirrors yourself) then you alienate large sections of your audience that are put off by that personality, and that’s an unfortunate defining aspect of Michael Bay’s films.

Michael Bay is certainly unique within the industry, which I guess is a triumph in of itself. He manages to continually deliver large scale productions, but is often condemned for being too self-indulgent. Nevertheless, one cannot take away the fact that he has skill as a filmmaker, at least when it comes to the production side. For someone who creates these massive scale productions, it is pretty remarkable that he’s able to deliver them on time and under-budget nearly consistently. One wonders if a messier, more craft obsessed approach might have made him a better storyteller. His style is still distinct and surprisingly influential. I’ve talked about the Bay affect on action films today, which has varying degrees of success. Bay even has some surprising fans out there, including an arguably way better director like Edgar Wright, who cites Bad Boys II as one of his all-time favorite movies. Wright even pays homage to the Michael Bay style with his spoof movie Hot Fuzz (2007). I won’t lie; not everything that Michael Bay has made has been terrible. I often find that he’s at his best when he’s working outside of his element. One of his best films is the little seen and very underrated The Island (2005), which has Bay working with a complex sci-fi concept and centering it around characters played by Ewan McGregor and Scarlett Johansson that are not cocky and are actually worth caring for. I kind of think that Bay missed the opportunity to improve himself as a filmmaker by latching on too quickly to success. If he had been brought through the ringer in order to make it into the industry, he might have turned into quite an accomplished storyteller given his skill with the camera. Instead, he’s become a product of the industry, someone there to churn out new product without ever taking any risks. That’s why he continually keeps making the same movies over an over again, because he doesn’t want to disrupt his flow of work. But as we’ve seen, a detour into the unknown has benefited him before. In the end, he is a divisive figure in the industry, because he is the very representation of the mundane in the Hollywood machine.