Stanley Kubrick was an enormously popular filmmaker not just among his peers and among film buffs, but also within the art community at large. The body of work that he has developed over the years has transcended all forms of art and collected all together, it is quite a sight to see on display. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) has always spotlighted the art of film within its galleries in the past. Given that it’s in the “entertainment capital of the world,” I would be shocked if they hadn’t. But I’m sure that few have been as impressive and as eye-catching as this recent exhibition on the filmography of Stanley Kubrick. Kubrick made only 13 films in his whole career, which doesn’t sound like much, but each one of those films is considered a classic and they are touchstones for both the film history and cultural history over the last 50 years. LACMA has put together an impressive collection of artwork, props, costumes and personal documents from each of Kubrick’s movies and has given everyone who visits a great visual history of both the man and his work.

Upon entering the gallery, you are greeted appropriately enough by a movie screen displaying selected scenes from Kubrick’s films. The next room opens up with a large display of film posters at it’s center. Some of the posters are pretty unique and ones I’ve never seen before, while others I’m sure can be seen hanging on the wall in any film buff’s home. Across the floor, there is an impressive collection of the camera lenses that Kubrick used on all of his films, including the Todd-AO lenses used on 2001: A Space Odessey (1968) and the extremely large, light sensitive lens used on Barry Lyndon (1975). The first room also showcases the early works of Kubrick, including Paths of Glory (1957), Spartacus (1960), and Lolita (1962). There is also a display of Kubrick’s collection of photos, taken during his early years as a photographer for Look magazine. It’s a lot to display in the first room, and I wish that there had been more emphasis on certain films, particularly with Spartacus and Dr. Strangelove (1963). I did however find the photography section fascinating, mainly because it shows how Kubrick trained his eye early on in photography, which would have a huge influence in the years ahead.

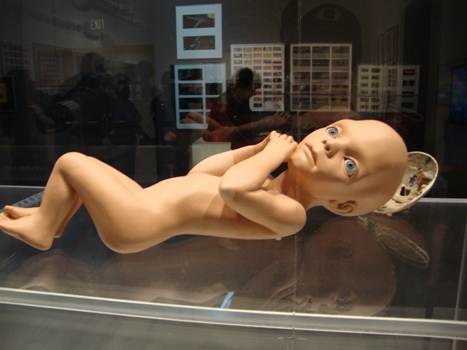

The next room highlights Kubrick’s most renowned film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. This section was the largest in the gallery, and definitely the most popular as well. On display are original costumes, as well as set pieces like the bright red lounge chairs found on the orbiting space station. You’ll also find elements used in the making of the special effects in the film, such as the miniature model of the spaceship and the “Star Child” itself. There’s a collection of research materials found throughout, which gives you a good idea just how well thought out and researched the whole film was. The displays are impressive, and this is where the exhibition really demonstrates why film art has it’s place within an art museum. Everything on display demonstrates the work that goes into creating a striking visual image, and each can stand on its own as a work of world-class art. This is the first room in the gallery that focuses on a singular film, but it’s not the last, as the gallery devotes the rest of it’s space to the later years of Kubrick’s career.

The next section showcases Barry Lyndon, which was a unique film in itself. The most interesting thing about the movie is that Kubrick used space-age technology to tell a very old-fashioned period piece. What he did was use very high tech cameras, with the same lenses used by NASA on the Hubble Telescope, to shoot interiors with no artificial light. It was a technique never done before on film, and it made Barry Lyndon one of the most intentionally artistic films in Kubrick’s career. It’s good to see that Barry Lyndon is given a lot of attention in this gallery, given how groundbreaking it was in terms of how it was shot. On display here is the actual “A” camera itself, along with a collection of costumes used in the film.

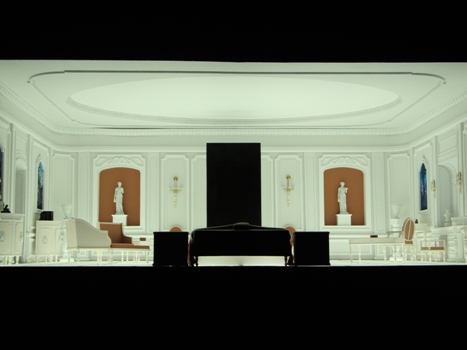

The next two rooms cover two of Kubrick’s darker films, A Clockwork Orange (1971) and The Shining (1980). These rooms are not quite as detailed as the 2001 room, but do feature some great pieces within. Primarily, there are a lot of the props from the films displayed here. You’ll find the mannequins from the Kerouva Milk Bar and the cane used by Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange, as well as the typewriter and fire ax props from The Shining. Also on display are some original costumes, including the dresses worn by the two girls in the hallway from The Shining. Both rooms also do a nice job of matching the color schemes of the two films, with Orange obviously dominating the first room, and stark white walls and blood red carpet dominating the room after it. Given that these are two of my favorite Kubrick movies, this was obviously one of my favorite sections of the gallery. They may not have been given the same amount of space as 2001, but it’s still a great display nonetheless.

Kubrick’s last films, Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999) are given less attention, with only a few props and documents available. The remainder of the gallery covers the research that went into a project that Kubrick never got to make. It was a film named The Aryan Papers, which would have been Kubrick’s attempt at a Holocaust film. Kubrick poured a lot of time and effort into researching the story, but he ultimately abandoned it mainly because Schindler’s List (1993) was about to be released by Kubrick’s friend Steven Spielberg, and because he believed that it was too depressing a subject matter for him to get right. This section as well as other sections devoted to abandoned projects by Kubrick, like Napoleon and A.I. Artificial Intelligence, give a fascinating look into what might have been. The Napoleon project in particular looks like it could have been a very impressive epic, and some of the location research into authentic French palaces gives a nice sense of the kind of scale Kubrick was going for. It also helps to underline the overall theme of the gallery, which is to show the evolution of an artist from one project to another.

Overall, this was a worthwhile exhibit to visit and I recommend it to anyone who is a fan of both art and film. Residents in Los Angeles should hurry though, since the exhibition ends on June 30th, meaning this is the final week to see it. Admission to the gallery is $20 for adults and it includes admission to all other galleries at LACMA, which has a very impressive collection of both classic and contemporary art. The Kubrick exhibit was definitely the highlight of my trip, given how much a fan I am of film in general. As a writer, I especially liked the fact that every section of the gallery included Kubrick’s personal copies of the scripts for each pertaining film. You get to look over the notes he written on certain scenes, which gives a glimpse into seeing the artist cultivating new ideas on the fly. There’s so much I could go on about, but it’s better to see it for yourself if you can. Kubrick is a filmmaker worthy of a place within an art gallery and LACMA should be proud of the show they put on in honor of this visionary man.