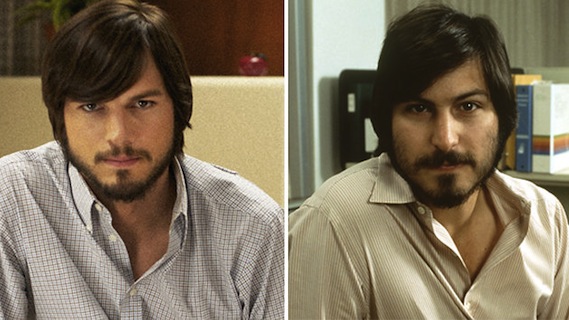

This week, two very different biopics open in theaters, both ambitious but at the same time controversial. What we have are Ashton Kutcher’s Jobs and Lee Daniel’s:The Butler (you can thank uptight Warner Bros. for the title of the latter film.) Both are attempting to tell the stories of extraordinary men in extraordinary eras, while at the same time delving into what made these people who they are. But what I find interesting is the different kinds of receptions that these two movies are receiving. Lee Daniel’s The Butler is being praised by both audiences and critics (it’s receiving a 73% rating on Rottentomatoes.com at the time of writing this article) while Kutcher’s Jobs is almost universally panned. One would argue that it has to do with who’s making the movies and who is been cast in the roles, but it also stems from larger lessons that we’ve learned about the difficult task of adapting true-life histories onto film. The historical drama has been a staple of film-making from the very beginning of cinema. Today, a historical film is almost always held to a higher standard by the movie-going public, and so it must play by different rules than other kinds of movies. Often it comes down to how accurately a film adheres to historical events, but that’s not always an indicator of a drama’s success. Sometimes, it may work to a film’s advantage to take some liberties with history.

The Butler and Jobs make up what is the most common form of historical drama; the biopic. In this case the subjects are White House butler Cecil Gaines, portrayed by Oscar-winner Forrest Whittaker, and visionary Apple Computers co-founder Steve Jobs. Both are men who hold extraordinary places in history, but in very different ways. Despite the differences in the subjects, it is the history that surrounds them that plays the biggest part of the story-telling. Filmmakers love biopics because it allows them to teach a history lesson while at the same time creating a character study of their subject. Usually the best biopics center around great historical figures, but not always. One of the most beloved biopics of all time is Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980), which tells the story of a washed-up heavyweight boxer who was all but forgotten by the public. Scorsese was attracted to this little known story of boxer Jake LaMotta, and in it he saw a worthwhile cautionary tale that he could bring to the big screen. The common man can be the subject of an epic adventure if his life’s story is compelling enough. But there are challenges in making a biopic work within a film narrative.

Case in point, how much of the person’s life story do you tell. This can be the most problematic aspect of adapting a true story to the big screen. Some filmmakers, when given the task of creating a biopic of a historical figure, will try to present someone’s entire life in a film; from cradle to grave. This sometimes works, like Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emporer (1987), which flashbacks to it’s protagonist’s childhood years frequently throughout the narrative. Other times, it works best just to focus on one moment in a person’s life and use that as the focus of understanding who they were. My all-time favorite film, Lawrence of Arabia (1962) accomplishes that feat perfectly by depicting the years of Major T.E. Lawrence’s life when he helped lead the Arab revolts against the Turks in World War I. The entire 3 1/2 hours of the film never deviates from this period in time, except for a funeral prologue at the beginning, and that is because the film is not about how Lawrence became who he was, but rather about what he accomplished during these formidable years in his life. How a film focuses on it’s subject is based around what the filmmakers wants the audience to learn. Sometimes this can be a problem if the filmmaker doesn’t know what to focus on. One example of this is Richard Attenborough’s Chaplin (1992), which makes the mistake of trying to cram too much of it’s subject’s life into one film. The movie feels too rushed and unfocused and that hurts any chance the movie has with understanding the personality of Charlie Chaplin, despite actor Robert Downey Jr.’s best efforts. It’s something that must be considered all the time before any biopic is put into production.

Sometimes there are great historical dramas that depict an event without ever centering on any specific person. These are often called historical mosaics. Often times, this is where fiction and non-fiction can mingle together effectively without drawing the ire of historical nitpicking. It’s where you’ll find history used as a backdrop to an original story-line, with fictional characters participating in a real life event; sometimes even encountering a historical figure in the process. Mostly, these films will depict a singular event using a fictional person as a sort of eyewitness that the audience can identify with. You see this in films like Ben-Hur (1959), where the fictional Jewish prince lives and bears witness to the life and times of Jesus Christ. More recently, a film like Titanic (1997) brought the disaster to believable life by having a tragic love story centered around it. Having the characters in these movies be right in the thick of historical events is the best way to convey the event’s significance to an audience, because it adds the human connection into the moment. Titanic and Ben-Hur focus on singular events, but this principle can also be true about a film like Forrest Gump (1994) as well, which moves from one historical touchstone to another. Forrest Gump’s premise may be far-fetched and the history a little romanticized, but it does succeed in teaching us about the era, because it does come from that first-hand experience. It’s that perspective that separates a historical drama from a documentary, because it helps to ground the imagination behind the fictional elements into our own lives and experiences.

Though most filmmakers strive to be as historically accurate as they can be, almost all of them have to make compromises to make a film work for the big screen. Often, a story needs to trim much of the historical elements and even, in some cases, take the extraordinary step of rewriting history. You see this a lot when characters are created specifically for a film as a means of tying the narrative together; either by creating an amalgam of many different people into one person, or by just inventing a fictional person out of nowhere. This was the case in Steven Spielberg’s Catch Me if You Can (2002), which followed the extraordinary life of Frank Abagnale Jr. (played by Leonardo DiCaprio), a notorious con-artist. In the film, Abagnale takes on many different identities, but is always on the run from a persistent FBI agent named Carl Hanratty (Tom Hanks). Once finally caught, Abagnale is reformed with the help of Hanratty and the film’s epilogue includes the statement that, “Frank and Carl remain friends to this day.” This epilogue had to be meant as a joke by the filmmakers, because even though Frank Abagnale is a real person, Carl Hanratty is not. He’s an entirely fictional character created as a foil for the main protagonist. It’s not uncommon to see this in most films, since filmmakers need to take some liberties to move a story forward and fill in some gaps. Other films do the risky job of depicting real history and completely changing much of it in service of the story. Mel Gibson’s Braveheart takes so many historical liberties that it almost turns the story of Scottish icon William Wallace into a fairy-tale; but the end result is so entertaining, you can sometimes forgive the filmmakers for making the changes they did.

But while making a few changes is a good thing, there is a fine line where it can be a disservice to a film. It all comes down to tone. Braveheart gets away with more because it’s subject is so larger than life, that it makes sense to embellish the history a bit to make it more legend than fact. Other films run the risk of either being too irreverent to be taken seriously or too bogged down in the details to be entertaining. Ridley Scott crosses that line quite often with his historical epics, and while he comes out on the right side occasionally (Gladiator and Black Hawk Down) he also comes up with the opposite just as many times (Robin Hood, 1492: Conquest of Paradise, Kingdom of Heaven theatrical cut). Part of Scott’s uneven record is due to his trademark style, which services some films fine, but feel out of place with others. Tone also is set with the casting of actors, and while some feel remarkably appropriate for their time periods (Daniel Day-Lewis in Lincoln for example) others will feel too modern or awkwardly out-of-place (Colin Farrell in Alexander). Because historical films are expensive to make, compromises on style and casting are understandable for making a film work, but it can also do a disservice to the story and shed away any accountability in the history behind it. While stylizing history can sometimes work (Zack Snyder’s 300), there are also cinematic styles that will feel totally wrong for a film. Does the shaky camera work, over-saturated color timing and CGI enhancements of Pearl Harbor (2001) make you learn any more about the history of the event? Doubtful.

So, with Lee Daniel’s The Butler and Jobs, we find two historical biopics that are being received in very different ways. I believe The Butler has the advantage because we don’t know that much about the life that Mr. Cecil Gaines lived. What the film offers is a look at history from a perspective that most audiences haven’t seen before, which helps to shed some new light on an already well covered time period. With Jobs, it has the disadvantage of showing the life of a person that we already know everything about, and as a result adds nothing new to the table. Both films are certainly Oscar-bait, as most historical films are, but The Butler at least took on more risks in its subject matter, which appears to have paid off in the end. Jobs just comes off as another failed passion project. What it shows is that successful historical dramas find ways to be both educational and entertaining; and on occasion, inspiring. That’s what helps to make history feel alive for us, the audience. It’s the closest thing we have to time machines that help be an eyewitness to our own history. And when it’s a good story, it stays with us for the rest of our lives.