One of the best things to happen to cinema over the last few years has been the emergence of digital archiving. Sure, it is sad to see classic film stock disappearing as the norm, but there is a reason why movies are better suited for the digital realm. If you have a digital backup for your film, you are better able to transfer it, download it, and make multiple duplications without ever losing video or sound quality. When a movie exists as a digital file, it is set in stone visually and aurally as long as it is never erased. This has become beneficial for people out there who do consider film restoration a passionate endeavor in life. For years, film restorers have had to contend with the forces of time undoing all their hard work as they try to keep some of our most beloved films looking pristine. Now, with digital tools at their disposal, preservationists can undo the years of wear and tear on most old films and make them look even better than when they were first released. The advent of DVD and Blu-ray has given more studios a reason to go into their archives and dust off some of their long forgotten classics, and because of this, restorations have not only become a noble cause for the sake of film art, but also a necessity. While there’s no trouble finding most movies in any studio archive, there are a few gems that usually have alluded archivist whereabouts for years, and these are known to film historians as the “Holy Grails” of cinema.

It’s hard to believe that there was once a time when film prints were considered disposable. Back when the studio system was first starting up, it was commonplace for production companies to dispose of their used film stock once a film was no longer in rotation at the movie theaters. This was done so that they could either make room for new releases, or to prevent any accidents from happening at their studio. The reason film prints were considered dangerous to store in a warehouse back in the 20’s and 30’s was because they were made from nitrate, the same material used to make dynamite. Several fires have happened to film vaults over the years because of nitrate film spontaneously combusting, including a 1967 incident at the MGM Studios in Culver City, CA. Incidents like this, as well as the careless disposal of early films, are the reason why 90% of all films made before 1920 are lost to us today, according to Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation. It wasn’t until the mid-30’s that filmmakers like Charlie Chaplin and Cecil B. DeMille started to actively preserve older movies, and their efforts have helped to keep many of these classics alive. One thing that helped was the fact both Chaplin and DeMille had ownership over their work, so they could keep the original negatives preserved in their own collections and safe from studio hands. Also, by keeping their films in good condition and preserved well enough to have them screened over and over again, it helped to convince the studios that it was worthwhile to do the same.

Even with better efforts to keep films archived and in good condition, older film stock still wears out over time and with many of them still made out of very volatile materials, many have just rotted away to ash in the vaults. That is why many archivists have fully embraced the digital revolution, because it has enabled them to preserve many of these disappearing classics for posterity in a definitive way. But, before a film can be preserved, the damage must be undone, and again digital tools are what saves these movies in the end. There is a whole class of digital artist out there whose whole job is to scan older films from the best sources available and touch up the scratches and marks on every single frame. Now that High Definition has become the norm in home entertainment, the results of film restorations are held to a much higher scrutiny, and that has led many studios to take better care of their whole catalog of flicks, which is nothing but a good thing for cinema as a whole. The fact that some classic films like The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Casablanca (1943) look so good after so many years is a testament to the great efforts made by restorers over the years. It would be unthinkable to see these kinds of films all scratched up and with faded coloring, which is why film restorations has to be an essential part of the studio business.

But, while beloved classics benefit from better care, some films have not been so lucky. Early cinematic history is unfortunately a lost age for many film historians, because so much of it is gone. We only know that many of these movies exist purely because of documentation from their filmmakers, or from a piece of advertisement that has been uncovered in an archive or private collection. Sometimes movie trailers have popped up for a movie that no longer exists as a whole, like the early “lost” Frank Capra film called Say it with Sables (1928). There are a few that have risen above the rest as films that are clearly calling out to be rediscovered and preserved. These are the “Holy Grail” films, and some of them have become famous merely because of their elusiveness. Like Indiana Jones searching for the Lost Ark, film preservationists have searched the world over for any evidence of the existence of these “Holy Grail” pieces of cinema. Part of the allure of these films is the fact that they have remained unseen by the public for many years, and in some cases, never seen at all, and yet when given just one titillating glance from a press photo or from a storyboard proving their existence, it’s enough to send film nuts on a mad search.

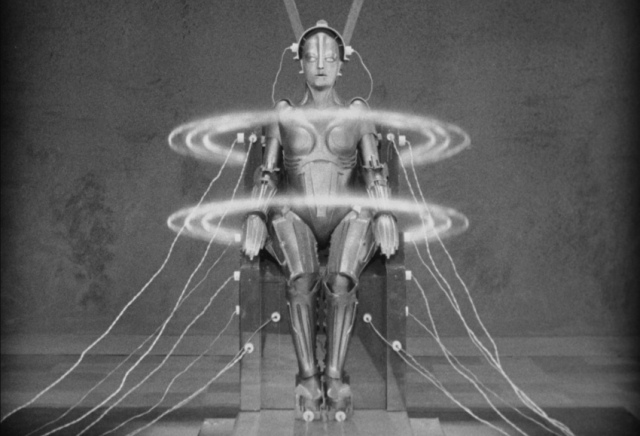

Probably the most famous example of a lost and found “Holy Grail” film is Fritz Lang’s groundbreaking classic Metropolis (1927). Lang’s film was made during the height of silent film-making and is considered to be the era’s crowning achievement. Made in Germany before the rise of Hitler, Metropolis was the most expensive film of it’s time, and showed to the world that European cinema was on par with the film industry emerging in Hollywood at the same time. However, when the movie made it’s debut in America, it was subjected to heavy cuts due to it’s more pro-Socialist themes, taking the run-time down from 145 minutes to just under 2 hours. The Nazi regime also destroyed most of the film’s early prints, as well as the original negatives, making a full restoration impossible to do over time. For years, the shorter cut of Metropolis was all that audiences had to see, and while it did regain it’s reputation as a cinematic classic, it remained an incomplete vision. Film preservationists had to fill in the missing gaps with title cards explaining what was missing for many years, but while a Blu-ray release was being prepped in 2008, something miraculous happened. A print of the original uncut version of the movie was found in Argentina in a private film collection. The Lang Film Foundation in Germany quickly picked up the find and made their best efforts to reincorporate the lost scenes. Even though the restoration couldn’t make the new scenes look as beautiful as the rest of the movie, due to the damage on the film stock, we are now fortunate to have a nearly complete version of this monumental film.

The saga behind the rediscovery of Metropolis’ uncensored cut gives many people hope that these “Holy Grail” movies can someday be found, and the odds of that happening improves more all the time. There is a more concerted effort to find lost treasures tucked away in film vaults across the world, and while some “Holy Grails” have remained elusive, the fruits of the film restorers’ labors are still reaping many rewards. Many of these finds have emerged from private collections and some unlikely places. Sometimes it’s thanks to a very forward thinking film technician or vault librarian who saved these treasures from early destruction, sometimes without even knowing it. A 1911 short movie called Their First Misunderstanding, the very first film to feature legendary actress Mary Pickford, was discovered in a New Hampshire barn in 2006. Even a simple mislabeling has been the fault of some of these classics being lost. The first ever Best Picture winner at the Oscars, 1927’s Wings, was considered gone forever due to negligent care of the original nitrate negative at the Paramount Studio Vault. But, the film was rediscovered in the Cinematheque Francaise archive in Paris, found almost by accident when the archivists were going through their back stock, and it was quickly given a more permanent and secure place in the Paramount vault.

Sometimes, like Metropolis, it’s not a whole film that gets lost, but rather fragments that are removed and then later discarded against the wishes of the filmmaker. These are not what we commonly know as the Deleted Scenes that inevitably have to be trimmed by the editor to make a movie work more effectively. What I’m talking about are pieces of the movie that are removed even after the film’s first premiere, leaving big chunks of the finished film out of the public eye for whatever reason. Sometimes these cuts were made because of censorship, and done at the protest of the filmmakers. Or they were trimmed for the purpose of time constraints. Back in the late 50’s and early 60’s, there was a trend for big Hollywood pictures to be shown as Roadshow presentations; meaning they were special events complete with printed out programs, musical overtures played while the audience took their seats, and special intermission at the halfway point of the movie. These were often 3 hour plus in length programs, so when these Roadshow movies had to make it to less grand theaters across the country, it meant that the whole show had to be trimmed to meet time constraints, including removing scenes from the actual movie. Recently, film restorations have tried to reassemble these old Roadshow versions, and while many of these have been found intact, like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Spartacus (1960), a few have still yet to be fully restored. Movies like George Cukor’s A Star is Born (1954) and Stanley Kramer’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) have been given partial restorations that do their best to make these films feel complete again with the best elements left available.

Sometimes, there are films that remain lost merely because they’re being withheld by a particular artist or by the production company that made it. This usually is because the film’s are an embarrassing black mark on the person or studio’s reputation and they would prefer that it remains unseen. But, the downside of withholding a known property is that it will inevitably raise people’s curiosity about these films, and it will in turn will put pressure on the filmmakers to make it available again. The most notorious example of this would be the 1946 Disney film Song of the South, which the Disney company refuses to release to the public, due to fears that it will spark controversy over its racial themes. Though not necessarily a “Holy Grail” film, due to the fact that it was available for many decades to the public and can still be seen by anyone who can secure a bootleg copy from Asia, we’ve still yet to see a fully restored version made by the Disney company. One withheld film that surely would be considered a “Holy Grail” type would be Jerry Lewis’ notorious film The Day the Clown Cried, which has been seen by only a small handful of people in Mr. Lewis’ inner circle. Supposedly because of the Holocaust setting and Mr. Lewis’ less than genuine depiction of the tragedy, the film has been kept hidden from the public, probably to spare Jerry from the controversy that could arise from it. Still, rare behind the scenes footage did emerge last year, which has raised people’s curiosity about it once again. We may someday get a true glance at both movies, but that choice is still determined by the ones who originally made them.

What I do love is the fact that film restoration is no longer looked at as just a noble cause, but rather an essential part of cinema as a whole. With data back-ups as common as they are now, we are far less likely to see catastrophic losses of film like we did before digital tools were made available to us. Today we can securely preserve the works of our present as well as restore the classics of our past. And the search for the most intriguing “Holy Grails” of cinema will undoubtedly continue to inspire both archivists and treasure hunters for years to come. Now that we’ve managed to see Metropolis become complete, the focus now shifts to the next big find, like the lost Lon Chaney thriller London After Midnight (1927), the most notable victim of the MGM fire; the lost director’s cut of Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons (1943); or the full 7 1/2 hour version of Erich von Stroheim’s legendary silent epic, Greed (1924). Some of these films may sadly be forever lost, but the hope always remains. The great thing about these searches though is that it demonstrates the importance of preserving our cinematic legacy. Martin Scorsese illustrated this idea beautifully in his 2011 film Hugo, where a young boy helps to rediscover a long forgotten filmmaker, whose legacy has all but disappeared due to the destruction of his original film prints. Thanks to passionate film preservationists like Mr. Scorsese and the people that work in film foundations and archives around the world, our cinematic legacy is no longer disappearing, but is instead coming back to life again more and more.