While the Criterion Collection is renowned for bringing to light obscure and forgotten cinematic works from across the world, they are also responsible for preserving some of the lesser known works of the great masters. Legendary filmmakers like Stanley Kubrick and John Ford have become a part of the Criterion library, with deluxe editions of some of their earlier films like Spine # 516 Stagecoach (1939) and #538 Paths of Glory (1957). While some of these may not be as obscure as other titles in the Collection, Criterion nevertheless honors these directors by giving worthy notice to a few of these films, showing just how important they are to the growth of cinema in general. In recent years, Criterion has also been looking for even more prestigious films to include in it’s library, including some of the most beloved movies of all time. Among their titles today are some Oscar-winners like Laurence Olivier’s 1948 Best Picture winner Hamlet (Spine #82) and Elia Kazan’s 1954 winner On the Waterfront (#647). Not only does the inclusion of these beloved masterpieces give a special acknowledgement to the filmmakers within the Collection, but it also shows that Criterion celebrates the Golden Era of Hollywood just as much as they do the art house scene. And one particular Hollywood master has been long celebrated as part of the Criterion Collection, all the way back to even the early years of the label. That director of course is the “Master of Suspense;” Alfred Hitchcock.

Hitchcock is widely considered to be one of Hollywood’s greatest filmmakers, if not the greatest. No other director was more consistent in Hollywood, while at the same time breaking new ground with every production. Most of his films are legendary; Psycho (1960), North by Northwest (1959), Rear Window (1954), and The Birds (1963) just to name a few. In fact, the British Film Institute, for the first time ever, named a Hitchcock film as the “greatest movie ever made,” that being 1958’s Vertigo; it took the honor away from Citizen Kane (1941), which held that spot for over 40 years. While these popular movies are kept in the public eye by the studios that made them, Criterion has also contributed greatly to showcasing the works of Alfred Hitchcock. At one point, the Criterion Collection had seven Hitchcock films in their library. These included the movies made during Hitchcock’s first few years in Hollywood; 1940’s Oscar-winner Rebecca (#135), 1945’s Spellbound (#136) and 1946’s Notorious (#137). These Criterion editions have unfortunately gone out of print, and have returned back to their original studios for new editions, but Criterion still maintains the licence to a few other Hitchcock titles. These are mainly the ones that were released during the earliest part of his career, back when he was still cutting his teeth in the British film industry. It’s interesting looking back at this period in Hitchcock’s career, as we see the beginning of some of the things that would become synonymous with Hitchcock’s later work. And if there is one Criterion film that best illustrates the beginning of the Hitchcockian style, it would be 1935’s The 39 Steps (Spine #56).

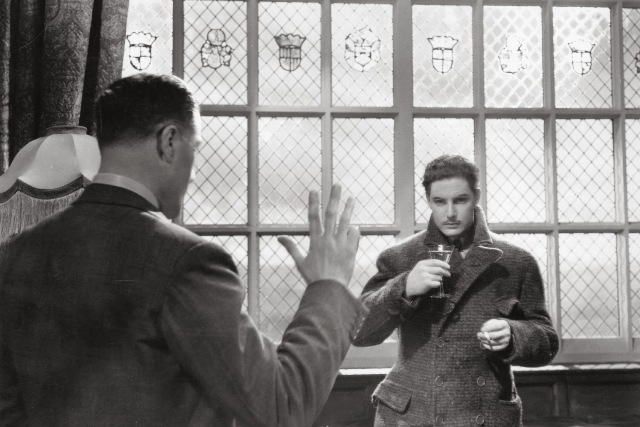

The 39 Steps is probably the best known of Hitchcock’s British films, though it doesn’t quite receive the same recognition that his later flicks do. But, even so, many of the director’s trademark elements are there, and in many ways 39 Steps helped to set the standard for all of those that followed. In particular, it began the “wrong man” scenario that would become a popular theme in most of Hitchcock’s later films. The story follows a young Canadian traveler Richard Hannay (played by Robert Donat) who finds himself wrongly accused of murder when an undercover spy (Luccie Mannheim) is found dead in his flat. In her possession is a map to Scotland, which he uses to track down the people responsible for the murder, while at the same time avoiding getting caught himself. Upon investigating the clues along the way, he learns that the head of the spy ring responsible for killing the girl is missing the top joint of one of his fingers, and he also discovers something known only as “the 39 steps”. He escapes capture on the Scottish Moors, after being recognized by a fellow traveler named Pamela (Madeline Carroll) who believes he’s the murderer. He soon finds refuge in the home of a respectable Scottish scholar, Professor Jordan (Godfrey Tearle) who is willing to hear Richard’s side of the story. Richard makes his plea and feels safe in the Professor’s estate; that is until he discovers that the Professor has a missing joint on one of his fingers. Richard, having learned the identity of the true murderer, soon finds himself on the run again, only this time determined to learn the secret of the “39 Steps” before Professor Jordan can stop him, and learn what it has to do with a vaudeville performer named “Mr. Memory.”

The 39 Steps (1935) is small in scale compared to some of Hitchcock’s other great works, but all of the pieces are still there. In fact, this film helped to introduce many of Hitchcock’s most familiar trademarks. Apart from the obvious “wrong man” scenario, which would become a favorite theme in Hitchcock’s later works like North by Northwest, this film also introduced the idea of the MacGuffin to the cinematic language. A MacGuffin is a cinematic term, coined by Hitchcock himself, that refers to the thing that the main characters are searching for, but in the end turns out to be something inconsequential to the audience. In other words, it’s the thing that drives the motivations of the plot; making the directive more important than the actual reward. Hitchcock’s uses of a MacGuffin in a movie are pretty noteworthy and here it’s pretty much the focus of the entire film. In the end, we learn what the 39 Steps is during the final scene, but that piece of information really amounts to very little. What we remember is the heart-pounding search to find it, and that’s what Hitchcock is known best for. He was the “Master of Suspense” for a reason, and this film clearly shows how he refined his cinematic voice around this trademark. You can also see in this movie how the director was finding his style as well. The film features stunning camera work, which helps to elevate the suspenseful nature of the movie very well. The scenes in Scotland in particular have a nice gloomy feel to them. But, it’s the use of close-ups and quick-editing where we see the Hitchcock of later years start to develop, and it’s clear to see how this same filmmaker would redefine Hollywood movie-making in the years to come.

Does the film hold up against it’s more famous descendants? It’s hard to put this film in the same category as some of Hitchcock’s later classics. After all, Hitchcock’s prime was really in the 1950’s, when he pretty much could do no wrong. The Hitchcock of the 1930’s was still trying to figure things out and probably didn’t have the same kind of control over his vision that he soon would have. At the same time, The 39 Steps is still a very effective movie, and still holds up as a great example of early suspenseful story-telling. Robert Donat makes a fine leading man in the film, playing the determined and resourceful Hannay with a lot of charm. He embodies that “every man” sensibility that Hitchcock always loved to put into his main characters, and he gives the character a believable intelligence throughout. The writing also retains much of that classic British wit that Hitchcock’s films are known for, especially the earlier ones. It’s clever, without being too complicated, and it treats it’s audience intelligently, never resorting to spelling things out for us. Hitchcock’s macabre sense of humor is also present in the movie, albeit more subdued here than in many of his later films. Also, the black-and-white cinematography is gorgeous, showing Hitchcock’s keen eye for composition. If the film has a major flaw, it’s the fact that it feels small. The film is relatively short at 86 minutes, compared to Hitchcock’s later films which ran on average around 2 hours. While it does fill it’s run-time with plenty of story, it feels like more could have been built upon the mystery. Instead, the majority of the movie gives us the typical man on the run scenario, which gets worn out by the 1 hour mark. Thankfully, the film finishes strong with a very memorable climax. It’s clear that Hitchcock was still trying to figure out the “wrong man” narrative here, and this film feels like a good test run for his later movies like North by Northwest.

Criterion, of course, treats all of it’s new titles with special care, and Hitchcock’s 39 Steps is no different. Given that the movie is very old, it needed to be given a special restoration in order to bring out the best possible image quality. The 39 Steps was selected as a Criterion title very early on, and was released on DVD way back in the late 90’s. The image quality of the DVD release was passable, but nowhere near what the film should actually look like. So, when Criterion prepared the film for a Blu-ray re-release in 2012, they gave the movie a proper high-definition restoration. The results of Criterion’s efforts are astounding. The film, naturally, hasn’t looked this good in years. While still maintaining the grainy look of a film it’s age, the restoration has helped to boost the levels of sharpness and detail to the image. Color contrast is always something to take into consideration when restoring a black-and-white film, and here the gray levels contrasted with the blacks and whites feels a lot more natural and authentic. The sound quality has also been cleaned up, and is now free of the pops and buzzes that usually plague an older soundtrack. Is it the best possible picture and sound that we’ve seen from Criterion. Unfortunately, the original film elements were unavailable to Criterion, due to the original negative being lost to time. But, Criterion did the absolute best that they could here, and the film has thankfully been cleaned up and preserved digitally for all of us to enjoy. Given that it’s Hitchcock, the standards are pretty high, and Criterion does the legacy proud here.

The Criterion edition also features a good sampling of bonus features, many of which were carried over from the original DVD. First off, there is an Audio Commentary by Hitchcock scholar Marian Keane. Ms. Keane’s commentary is more of a lecture style analysis of the movie’s larger themes and the film’s lasting legacy. This isn’t the kind of commentary track that you listen to for a breakdown of how and why the film got made, like so many director’s commentaries do. This is more like the kind of analysis that you would hear in a college level film course, which is not bad if that’s something that interests you. Marian Keane’s analysis is informative and well-researched. Just be warned that it’s also very scholarly as well, and in no way substitutes for a behind-the-scenes look. A documentary included on the disc does however go into the making of the film a little bit more. Also carried over from the DVD is Hitchcock: The Early Years, which details the director’s early films made in his native England, including this one. A complete radio dramatization is also present on this edition, created in 1937 for the Lux Radio Theatre show and starring Ida Lupino and Robert Montgomery in the roles of the main characters. New features added exclusively for the blu-ray edition include footage from a 1966 interview with Hitchcock done for British television, where he talks a little about the making of this film. Also, another Hitchcock scholar, Leonard Leff, recorded a visual essay, which goes into further detail of the film’s production. Rounding out the special features is a gallery of original production design art, as well as an excerpt from another interview of Hitchcock, conducted by another filmmaker, Francois Truffaut. All in all, a very nice set of features that makes this set feel very well-rounded.

If you consider yourself a huge fan of Alfred Hitchcock, chances are you already are familiar with The 39 Steps and it’s place within the master’s entire filmography. While it may not be as exciting as North by Northwest, or as chilling as Psycho, or as emotional as Vertigo, it nevertheless represents a nice stepping stone towards some of those later masterpieces. I certainly look at it as a prime example of Hitchcock’s earliest work, because you can see all the elements there that would come to define his entire career. It’s movies like The 39 Steps that really illustrate perfectly the maturing of a filmmaker, and even though it doesn’t reach the heights that we know now that Hitchcock was capable of, it still stands on it’s own as a fine piece of entertainment. I certainly recommend it for anyone who just wants to see a good old fashioned spy movie. There were many others like it at the time, but few feel as effortless in it’s suspense as The 39 Steps does. There are other Criterion editions of films made during Hitchcock’s early years, and they are worth checking out too, like 1938’s The Lady Vanishes (Spine #3) and 1940’s Foreign Correspondant (#696), which was the last film Hitchcock made before his move over to American cinema. The 39 Steps unfortunately has been overlooked over the years as a defining film in Hitchcock’s career, so this Criterion edition is a welcomed spotlight for a movie that is deserving of it. It’s always great to see where the beginnings of a great filmmakers style came from, and The 39 Steps is the kind of movie that shows that off perfectly. Hitchcock holds an honored place in the Criterion Collection, and hopefully that spotlight will continue to extend to many more of the director’s great early films.