Christmas movies and prestige cinema have never really mixed well together. Considering that Christmas has become such a commercial holiday over time, it’s not surprising that Christmas themes have become abundant in commercial films as well. Though not always a negative thing for both the movies and the holiday they reflect, it’s pretty safe to say that most Christmas movies tend to be safe and formulaic family fare. Rarely do you see a Christmas movie that deals with button-pushing issues or harsh, negative themes. The point of the holiday is to rejoice and be festive after all. But there are some Christmas movies out there that have taken risks and still delivered a powerful presentation of the holiday spirit. In some cases, these movies end up being some of the most beloved classics of the holiday season; Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) is probably the best example, given that it touches upon themes of depression and suicide in it’s story-line. Sometimes it helps to add a little spice to the sugar and address the darker side of the holiday season in order to make us better appreciate the good things. The Criterion Collection, always a home to movies that represent the many dual layers of the human experience, has also become the home to many holiday themed films as well that share this complexity. Some are very strongly centered around the holiday, like French director Arnaud Desplechin’s 2008 film A Christmas Tale (Spine #492), while others use the season as a backdrop for a larger narrative, like Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955, #95) or Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm (1997, #426). But, if there was a title in the Criterion catalog that makes the most of it’s Christmas setting and has won the acclaim of critics and cinephiles alike, it would be Swedish director Ingmar Bergman’s 1982 masterpiece, Fanny and Alexander (#261).

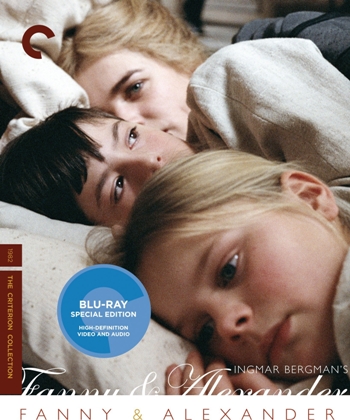

Ingmar Bergman is a favorite among the Criterion publishers, and is competitive with the likes of Akira Kurosawa for having the most titles to his name under the Criterion label. Bergman’s filmography is lengthy and varied, but they are all well defined by the director’s very distinct and recognizable style. Both a renowned director on the silver screen and on the stage, Bergman’s style is very earthbound and confined to small, intimate portraits of ordinary life. That’s not to say that he doesn’t take flights of fancy every once and a while, but even those moments have a cold, stoic nature to them. Bergman can be an acquired taste for some people. His movies often are sometimes so devoid of kinetic energy that it may leave some audiences bored. But no one can deny the visual power that his movies often have. In many ways, Bergman is the Grandfather of modern Scandinavian cinema, and many filmmakers who have come up in the years since from Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark have in one way or another drawn inspiration from his films. Even some American filmmakers have been inspired by Bergman’s work; probably the most surprising would be Woody Allen, who credits Bergman as a direct influence. Of course, Criterion has honored Bergman with many fine editions of his most noteworthy movies, including his first international hit and probably his most famous overall film, The Seventh Seal (1957, #11). Other noteworthy hits like Persona (1966, #701), Wild Strawberries (1957, #139), and Autumn Sonata (1978, #60) have also made it into the collection. But Fanny and Alexander holds a very special place in the collection, not just for it’s reputation as a movie, but because it also marks the end of an era. Fanny was to be Bergman’s final theatrical film as he decided to work solely on stage and television in the years after. He would come out of his semi-retirement in 2003 and direct one final film called Saraband, but that pales when compared to the effort he put into this project. It’s a spectacular feat of cinema, which Criterion has matched with an equally grand special edition.

Fanny and Alexander is an interesting film in the Bergman filmography mainly because of it’s epic scale, and also the fact that it centers on such a young protagonist, something that Bergman had never done in any of his previous films. While most of Bergman’s movies run at a brisk but methodically paced 90 minute average length, Fanny and Alexander runs a lengthy 187 minutes theatrically, which even itself was cut down from a staggering 5 hour long television version. Though the movie is nearly twice as long as most of Bergman’s other films, it’s understandable as to why. The story follows the tale of the wealthy Ekdahl family at the turn of the 20th century, led by their matriarch Helena (Gun Wallgren), and her three sons Carl (Borje Ahlstedt), Gustav (Jarl Kulle) and Oscar (Allan Edwall). Oscar, the elder son, has managed to successfully run his family’s theatrical business with wife Emile (Ewa Froling) and children Alexander (Bertil Guve) and Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) in tow. The close knit family spends a festive Christmas season together, showing how closely knit the whole of them are, but that joy is soon shattered when Oscar is stricken by a sudden stroke while rehearsing a play. After his death, Emile is in need of security for both the theater and for her children, so she turns to local Lutheran bishop Edvard Vergerus (Jan Malmsjo), who takes Emile and her children into his home after she agrees to their marriage. Soon after, things start to go sour as Bishop Edvard proves to be a cold, unloving husband and father. Emile resolves to end the marriage after she finds Alexander alone and bloodied in his room after a beating given to him by the bishop. However, a problem occurs when Emile ends up with child, and Bishop Edvard refuses to let his new family go. This resolves the extended Ekdahl family to take action and find a possible way to free Emile, Fanny and Alexander from the cruel bishop.

Naturally the primary theme of Fanny and Alexander is the bonds of family, and how festivities like Christmas keep those bonds growing stronger over time. The whole beginning of the story presents that idea perfectly with the extravagant party put on by the Ekdahls in both their theater and in their lavish home. The party is played out in extravagant detail, giving us an interesting and personal look at Swedish Christmas traditions as well as the intimate relationships between all of the characters, young and old. In the theatrical version, this Christmas celebration takes up nearly 40 minutes of run-time, and in the television version, it makes up the entire first 90 minute episode. It also marks the high point of Ingmar Bergman’s vision. In this scene alone, we see the director at his most lavish as well at his most introspective. The movie has been called semi-autobiographical, and that wouldn’t be surprising. Christmas celebrations like this were probably a major part of Bergman’s early life growing up in pre-WWII Sweden. It also marks a strong contrast with Bergman’s earlier, bleaker films in the post war years. Those films would often focus on shattered dreams and harsh realities with little in the way of solace. Not to mention, most of them were devoid of color. In this film, however, color is abundant. Fanny and Alexander is far and away the most extravagant of Bergman’s films, helped largely by the Oscar-winning set design, as well as the Oscar-winning cinematography by long-time Bergman associate, Sven Nykvist. But, the most interesting aspect of this opening Christmas celebration is how it contrasts with the latter, bleaker part of the movie. Once Bishop Edvard enters the picture, the whole movie pivots into a darker, more typically Bergman-esque narrative. This gives the pleasing Christmas scenes a interesting context within the movie, and also in Bergman’s own mindset. Is joy from festivities like Christmas the ideal that we want in life, or is it merely a dream that momentarily dulls the pain of reality?

This theme plays out in a very interesting way in the movie, because it is told entirely through the eyes of a child. Though the movie is named after the two siblings, young Fanny is actually more of a secondary character, as Alexander is the main protagonist. Bergman clearly drew upon his own experiences in childhood, but interestingly plays things in reverse in Alexander’s story. In reality, Ingmar Bergman was born into a stern, religious household and was constantly reprimanded by his authoritarian preacher father. He would later find escape in the world of theater and film, and while never really abandoning his faith, Bergman would always cast religious authorities in a negative light in most of his latter work. Alexander on the other hand was born into the theater, and grew up in a loving and imaginative household. It’s only when religious authority enters Alexander’s life that things start to fall apart. In many ways, the two fathers in Alexander’s life represent Bergman’s ideas between dreams and reality. Oscar is the father Bergman wishes he had, while Bishop Edvard is the father that he actually had. This is probably why the latter part of the movie feels so bleak, because of that loss of innocence. Bergman feels fortunate to have found joy in his ability to create, but he expresses great pity to anyone who has that taken away, like with Alexander. The movie does a brilliant job of expressing that duality, with the lavish and colorful Ekdahl residence contrasted against the stale, white walls of Bishop Edvard’s home. And although Fanny and Alexander portrays religious figures negatively, Bergman still presents a very spiritual side in the movie, as ghosts and ghouls roam free among the characters, especially in the imagination of Alexander, who often sees his lost father Oscar still roaming the hallways at a distance. It’s a deeply moving portrayal of childhood and growing adolescence, which is perfectly portrayed by young Bertil Guve as Alexander. Overall, he becomes one of Bergman’s most intimately interesting protagonists.

Upon it’s initial release, Fanny and Alexander was hailed as a masterpiece, and has steadily grown in reputation as one of cinema’s great classics. It’s often been called Bergman’s greatest achievement and the greatest Scandinavian film ever made, which is a high honor. So, given it’s monumental reputation, Criterion had to do something special with this edition, and they certainly delivered. First of all, it should be noted that the Fanny and Alexander edition not only contains one movie, but two by the famed director. In addition to directing the film itself, Bergman also had a second camera on his set to capture the whole process of him working behind the camera, which he later edited into a documentary called appropriately, The Making of Fanny and Alexander (1982). This feature length documentary is an interesting look at Bergman’s process, and how it often led to many struggles on the set, both internally and with the cast and crew. It’s an intimate portrait of the man himself and helps to really show the mind and method of an artist in a fascinating way. Overall, the presentation of the movie and the documentary comes in a lavish three disc blu-ray set. The theatrical edition is included, given a beautiful high definition remaster, as well as the lengthy television version, made available for the first time here in North America. The documentary makes up the third disc, along with all of the extras. Each of the different films on this set are given brilliant digital presentations that do justice to this over 30 year old film. The picture quality really brings out the lush colors of Sven Nykvist’s photography, and the sound presentation, although low-key generally, still feels true to life and sounds perfect. It’s a worthy visual and aural presentation that shows exactly why Criterion is the best home possible for Ingmar Bergman’s collection of films.

The extra features also help to fill out the set nicely. In addition to the colossal Making of Fanny and Alexander feature, you also get two other noteworthy documentaries on this edition. The first one is called A Bergman Tapestry, which gives you a comprehensive look at the making of the movie from the perspectives of the cast and crew, all looking back on their experiences with the director. The second documentary is a made-for-TV retrospective interview with the director called Ingmar Bergman Bids Farewell to Film. Conducted in 1984 by Swedish film critic Nils Petter Sundgren, the two men sit down and discuss Bergman’s career and why he decided (at the time) to stop making feature films. Fanny and Alexander is discussed extensively, as well as many of his other noteworthy works, and it’s an overall very enlightening interview that feels right at place in this set. The remaining supplements are extensive galleries of the many award-winning sets and costumes, showing just how much care went into the crafting of this film, and showing just how much Bergman wanted this film to glow visually. Rounding it all out, there is an audio commentary track by film scholar and Bergman biographer Peter Cowie, on the theatrical version only. In it, Cowie discusses the themes of the movie in more detail, as well as discussing the film’s place in Bergman’s whole filmography and it’s legacy. It may not seem like a lot on the surface, but each of these extra features are enormous in of themselves, especially the monumental Making of. It’s another sign of Criterion’s high standard, and of course they wouldn’t do anything other than the best for a film that is widely considered one of the greatest that’s ever been made.

Fanny and Alexander is a movie that needs to be seen by any film fan out there, especially those who want to expand their understanding of international cinema. Along with The Seventh Seal, this would be considered essential Bergman, and would probably be the best way to introduce the director’s work to someone who is unfamiliar with it. Do not be daunted by it’s epic length; Bergman fills every moment of this film with awe-inspiring artistry and doesn’t waste any of it on needless indulgence. In fact, for such a personal film, the movie is surprisingly accessible, and that’s probably because of the universal themes of family and coming of age that Bergman chooses to address here. Not only that but it has one of the most lavish and beautifully crafted visions of a Christmas celebration that has even been put on film. Upon seeing it, you can see why this movie is often considered a holiday classic, because few other Christmas movies feel this joyous about the holiday. It’s not cynical or shallow, and it shows what the holiday spirit should be all about, and that’s the bonds of family. I only wish that more Christmas adaptations would follow that example and stop sending bad messages in the guise of Christmas cheer (I’m looking at you Kirk Cameron). Ingmar Bergman has had the reputation of being a bleak and cold-tempered story-teller, which is sometimes reflected truthfully in his earlier films. But Fanny and Alexander presents something altogether different in the vision of hope, presented beautifully in the image of a family Christmas celebration. Hope and joy may be an unusual theme to find in a story made by the same guy behind the post-apocalyptic Seventh Seal, but Fanny and Alexander shows the legendary filmmaker at his most introspective and surprisingly, at his most optimistic. This treasure of a film gets a much deserved edition from Criterion and would make a very wonderful gift under the tree for any cinephile this year.