Films roughly fall into four separate categories. There are the ones that we love, the ones that leave us conflicted or indifferent, or the ones that just plain suck. Ninety percent of all movies fall into these three categories, but there’s that last ten percent that make up a whole different category. These films are the ones that defy all categorization and are mainly there to leave us wondering how in the world they exist at all. And this is by far the most interesting class of film out there. We all know what they are; movies that are so bizarre and defy all logical explanation. You would be led to believe that movies such as these are usually terrible and some of them certainly are, but their awfulness is also what makes them entertaining to audiences. Sometimes, this fourth class of cinema can even carry more of a devoted following than something that was competently made. How and why this happens is almost impossible to predict. Sometimes it’s the discovery of the unusual that drives their popularity and helps to carry their legacy on long after their initial release. Most cult movies start out as low budget failures and end up finding their audiences through word of mouth, and usually the odder the movie, the more appeal it will have with audiences who are attracted to that sort of entertainment. Such is the case with something like The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), which opened small, but has continually been running now for 40 years as a staple of midnight screenings across the world. But Rocky Horror is just one of many movies that have left their mark on cinema and not by being the best made or the most moving, but instead by being the most unexplanable. And if there is anything that most of these movies have in common, it’s that they came from the minds of ambitious yet eccentric people.

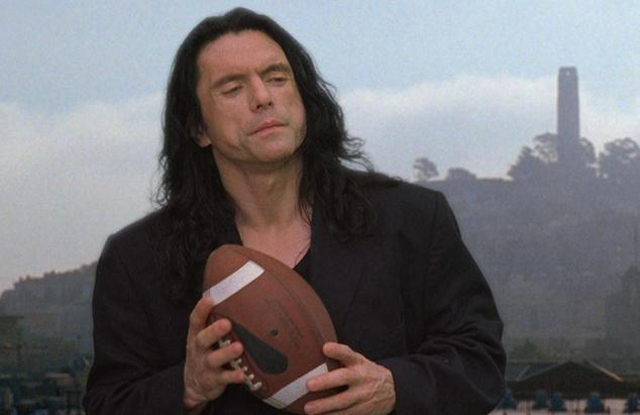

Probably the most notorious creation in recent years from a truly unusual mind would be 2003’s The Room; one of the most bizarre movies that has ever been made. The Room is a movie that really defies all reasonable explanation. On the surface, it doesn’t seem like much; just a small budget drama about selfish people falling in and out of relationships within the backdrop of San Francisco. But what makes the movie notorious is the fact that every film-making choice, whether it’s the editing, the music, or the staging, is absolutely wrong. Scenes exist for no purpose (like the famous flower shop scene), characters pop-up out of nowhere with no context or set-up, and the dialogue is completely tone deaf (“I got the results of the test back. I definitely have breast cancer.”) Normally you would think that a mess of a movie like this would make the film forgettable, and yet the sum of all these bizarre film-making choices makes The Room one of the most unintentionally funny movies ever made. It’s especially entertaining to watch this movie with a full audience, just to hear peoples’ reactions to what they’re watching. This is why The Room has now become one of the most popular cult hits of the last decade. Anybody could have made a bad movie, but it had to take a very special, twisted mind to have made something as hilariously inept as The Room, and that special person was writer, director, and star Tommy Wiseau. Tommy was a struggling actor with no film-making expertise. Yet, he had endless ambition and The Room was his pet project from start to finish. I think that part of the reason The Room succeeds where other bad movies fail, is that no one stood in Tommy Wiseau’s way and made him second guess himself, leading to a finished product that thinks it’s a movie but really ends up becoming a fascinating enigma.

With films that come from unchecked egos like Tommy Wiseau’s, we are able to get a fairly good insight into the mind of a director and how they view the world and tell it’s story. Film-making is a trade based mostly around compromise, but the more you strip away outside influences, like studio heads and focus groups, you begin to see stories told on a more personal level, especially when the director has full control. There are many different kinds of directors, but the most celebrated are the ones who have completely control over their voice and their style. Usually, these types of directors write their own scripts and do their own editing, and in some more extreme cases (like Steven Soderbergh or Robert Rodriguez) do their own camera work and scoring. For many of these celebrated directors, it usually takes many years to refine their craft, whether it be by apprenticing on film sets or attending film schools. But, with the democratizing of media and the wider availability of film-making tools, we are seeing more people today taking it upon themselves to create their own movies, whether they have the know how to do so or not. Sometimes you have people who have natural talent as filmmakers, and then you have people like Tommy Wiseau, who are ambitious amateurs in the most extreme sense. The charm that comes from Wiseau’s folly is the fact that he put so much money and effort into the movie, spending his own fortune buying camera equipment and renting studio space, without ever trying to learn the language of film. People might see that as lazy, but there is something endearing about Wiseau’s desire to create, even if he’s not the most qualified to do so.

Tommy Wiseau isn’t alone in this field, because he does come from a long line of failed filmmakers with vision but no skill. The B-movie craze of the 50’s and 60’s was an especially strong time for amateur filmmakers. Many would prove to be forgettable, but some had such unusual visions, that even their failures have withstood the test of time. One such director was Edward D. Wood Jr., who’s responsible for making what many consider to be among the worst movies ever made. His notorious filmmography includes bizarre movies like the cross-dressing comedy Glen or Glenda (1953), the schlocky Bride of the Monster (1955), or his magnum opus Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959), each one crazier than the last. Critics of course decried the amateurishness of Wood’s films, but audiences who rediscovered the movies years later found his flicks to be peculiar little oddities that carried their own charm. They are horrible, of course, but almost to the level that they stand out from all other movies of their kind. Like Tommy Wiseau, Ed Wood was driven by the sensation of creating a movie, and his ambition was unchecked by the limitations of his skills as a filmmaker. In a sense, the reason why we enjoy Ed Wood movies is because there’s no pretentiousness to them. They are what they are and in the end we only see the zaniness of Wood’s vision. Director Tim Burton perfectly captures this creative drive from Ed Wood in his 1994 biographical film about the director. That movie helped to craft the image of Ed Wood as a hero for any aspiring filmmaker hoping to fulfill their dreams, while also warning them to refine their skills and avoid Wood’s mistakes. But, at the same time, you also needed a filmmaker with a twisted mind like Burton to tell the story of someone like Ed Wood and stay true to his spirit.

A directors’ vision ultimately determines whether or not a film can connect with it’s audience. The reason why Wiseau and Wood are celebrated even despite their faults is because their movies are unforgettable. Yes, part of why they leave an impression is because we marvel at just how bad they are, but even still that’s something that can ultimately keep a movie alive for generations. The movies that usually fail in the long run are the ones that are bad and forgettable. Even with all the cinematic tools at their disposal, Hollywood filmmakers can still create some truly horrible films that burn out just as quickly as they are made. Case in point, Roland Emmerich; a man who’s become synonymous with big budget disaster flicks like The Day After Tomorrow (2004) and 2012 (2009). His movies are almost always mired in ham-fisted sermonizing about politics and the environment along with high-quality visual effects that ultimately all just looks the same in the end. They lose their punch quickly and end up being more laboured than fun. Contrast this with the movie Birdemic: Shock and Terror (2010), directed by former tech salesman James Nguyen, which has the same sermonizing but with far more amateurish visual effects and storytelling. Emmerich’s films fall by the wayside while Birdemic has since achieved cult status. But, why is that? It seems to be the fact that Emmerich’s movies try too hard to connect with it’s audience, while Birdemic just doesn’t even try. It’s the movie that James Nguyen wanted to make, regardless if he was qualified to do so. Like Wood and Wiseau, Nguyen’s vision is on display and it’s charmingly naive. And that’s what ultimately makes Emmerich’s movies fall short; the lack of charm and the insistence that it be taken seriously.

But, even though most strange movies come from amateurish filmmakers, it doesn’t mean that it’s always the case. Even some of cinema’s greatest minds have found themselves in the middle of creating some truly bizarre movies, and all with the backing of the studios as well. Who would’ve thought that someone as skilled as Stanley Kubrick could have made something as out of this world and undefinable as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or take a radioactive lightning rod of a novel like A Clockwork Orange and make it into a work of art; but he did just that. A director’s vision can ultimately take on any form, even in the realm of the bizarre. The 1970’s was a particularly big period for oddball films, and many button-pushing filmmakers made a name for themselves in these years, like Ken Russell with his gonzo condemnation of religion in The Devils (1971), John Boorman with his oddball sci-fantasy Zardoz (1974), or the many art house, free form pictures made by Andy Warhol. But, even interesting cinematic experiments can come from great artists who cross into a point of insanity when creating a high profile movie. Such a thing happened to Francis Ford Coppola, who had to be dragged away from the set of Apocalypse Now (1979) because he wouldn’t stop filming, and was desperately trying to make sense of a project that was driving him crazy. Martin Scorsese likewise made Taxi Driver (1976) in a haze of delirium, fueled by his then addiction to cocaine. Luckily for both men, those crazed states helped them create long lasting works of cinematic art, but it’s not without consequences. Hollywood let these big projects go too far many times and ultimately had to pull the plug when director’s egos got out of hand, which is what happened to Michael Cimino and his mess of a movie known as Heaven’s Gate (1980).

Whether strange and twisted movies happen by mistake, or by design, it is ultimately up to the audience to decide. Usually it isn’t just the movie itself that builds the legend around it, but rather the story behind it’s making. We are fascinated just as much about the creators as we are about the creations and by watching the movies themselves, we get to see just a little bit of the madness that drives them. That madness is what we ultimately find fascinating. Tim Burton’s Ed Wood found the story of a dreamer who wanted to tell stories in unusual ways in the background of it’s subject, and that helps us modern viewers see movies like Plan 9 in a whole new way. The same is holding true for The Room, which itself is gearing up to have it’s creation chronicled in an upcoming comedy starring James Franco as Tommy Wiseau. That’s a true indication of how fascinated we’ve become with these strange, oddball films. Even great filmmakers with complete and competent visions can develop a cult status by taking some very unorthodox routes and become legendary as a result. There are stories within stories of the origins of these movies, especially when you study the strange and sometimes dangerous film-making techniques of directors like Stanley Kubrick or Werner Herzog.

But, the things that really set these movies apart is that they defy explanation. Their existence is so baffling that it makes each of them a minor miracle, which in turn leads them to be celebrated. They are even more special if they are rediscovered many years later and completely out of the blue, like Manos: The Hands of Fate (1966) or Santa Claus Conquers the Martians (1964). These are the Outliers of cinema and they ultimately reinforce the power that the medium can have. By embracing the bizarre, we can see the limitless potential of cinema, and how no vision is too strange. Even if talent behind the camera exceeds the likes of Tommy Wiseau, he still managed to do what most filmmakers have always dreamed of doing and that’s to have their movie be seen by audiences around the world. Of course, part of The Room’s success is because we watch just to laugh at it, but still that makes it more entertaining than most of the junk that Hollywood usually puts out. In the end, it helps to be the oddball in an artistic world. That’s why we hang paintings of a Campbell’s soup can in the same gallery as a Rembrandt or play a Beatles song in the Royal Albert Hall in London. We gravitate to what entertains us, and it’s just fine if it’s from the mind of a spirited yet not completely normal creative mind. And sometimes the crazier the mind is, the more unique the end result will be.