Though visual effects have been a part of cinema since the very beginning, it’s only been in the last 3 decades that we’ve seen huge leaps and bounds made thanks to Computer Generated Imagery (CGI), up to the point where anything is possible on film. It has been an undeniable driving force of change in both how movies look compared to several years ago, as well as what kinds of movies can be made. We have visual effects to thank for making worlds like Middle Earth and Narnia feel like they actually exist, and for also making extraordinary events here on Earth seem all the more tangible on the big screen. But, even with all the great things that computers can do for the art of cinema, there is also the risk of having too much of a good thing as well. While CGI can still impress from time to time, some of the novelty has worn off over the years as techniques have become more or less standardized. Hollywood sadly seems to value CGI perhaps a bit too much and their over reliance on the medium has unfortunately had the effect of making too many movies look artificial. The curious result of this is that it’s making movies that use practical effects and subtle CGI look far more epic and visually impressive than the films that use it in abundance. Part of this is because more of the audience is able to tell the difference between what’s digital and what’s real today than they have before, and two, because we also admire the work put into something hand crafted. Using CGI for filmaking is not a bad thing at all; it’s just that there has to be a purpose and necessity for it to work.

The sad reality of the last decade or so is that filmmakers have seen CGI as a shortcut in story-telling rather than as an aid. Back in the early days of CGI, filmmakers were limited by what computers were capable of rendering at the time, so if they had to use them, it needed to be perfect and absolutely crucial. Now, anything can be rendered realistically, whether it be an animal, a place, or even a person, and it comes very close to looking 100% authentic. But, even with all these advancements in technology, filmmakers are still learning the best ways to use them, and sometimes quantity trumps quality in many cases. Usually it’s a decision dictated more by studios and producers who want to save a buck by shooting scenes in front of a green screen instead of on location, but then there are also filmmakers who have indulged too much in CGI effects as well. Thankfully, there are filmmakers out there who insist on using the tried and true practical effects, but their impact doesn’t extend to the whole community. As it is with all of filmmaking, it’s all about story in the end, and whether or not the tools that you have are able to serve it in an effective way. Would you rather watch CGI bring to life a talking raccoon and his tree monster friend, or do you want to watch two hours of CGI animated robots fighting? It really comes down to what impresses us the most and usually the quality of the movie itself factors into that. But, despite the quality of the flick and it’s effects, there seems to be a lot of bingeing going on with regards to CGI effects and it makes you wonder if Hollywood is doing a disservice to itself by not diversifying.

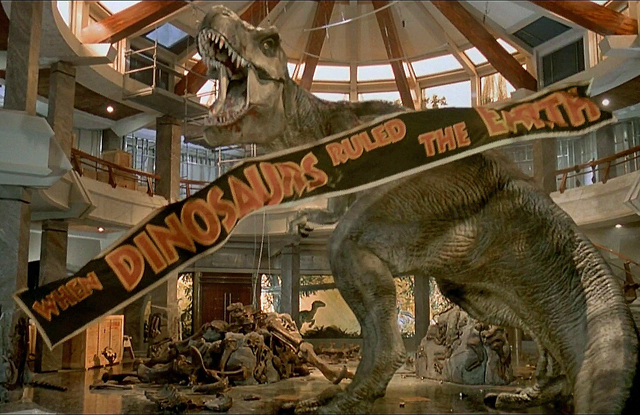

It helps to look back at a time when CGI still was a novelty to see where it’s value lies. Developed in the late 70’s and early 80’s, CGI saw some of it’s earliest and briefest uses in movies like Star Wars (1977). A few years later, Disney created the movie Tron (1982), which made the use of CGI environments for the first time in film, albeit on a very primitive level. But, even with Tron‘s limitations, it still showed the promise of what was to come, and it stood out strongly in an industry that still valued practical effects like matte paintings and models. Soon after, the movie Young Sherlock Holmes (1984) introduced the first integrated CGI effect into a live action film (the stained-glass knight scene) which paved the way for more digital additions in movies. And then, in 1993, we got the mega-hit Jurassic Park. Directed by Steven Spielberg, Jurassic Park was the biggest lead forward in CGI that the industry had seen to date, and that’s because more than any other film before it, we saw the true potential of what CGI could create. Naturally it helped to have someone like Steven Spielberg at the helm, given his comfortable history of using special effects in his movies, but this was on a level unseen before. Originally, the plan was to use stop motion animation to bring dinosaurs to life in the film, just because it was the standard in Hollywood ever since the brilliant Ray Harryhausen made it popular. Thankfully, engineers at ILM (Industrial Light & Magic) convinced Spielberg to take the risk and the result brought us Dinosaurs that both looked and moved realistically. Only CGI could’ve made those creatures move as smoothly as they did, and since then, it has been the go to tool for bringing to life characters and creatures that otherwise could never exist.

But, what is even more remarkable about Jurassic Park‘s legacy is not just the fact that it was a great movie with amazing effects, but it’s also a film that has remarkably held up over time. It’s unbelievable to think that the movie was made over 20 years ago at a time when CGI was still maturing. You would think that time would make the movie look dated now, but no; the CGI still holds up. This is partly due to the filmmakers who busted their butts to make the CGI look perfect, but another reason is also because the CGI animation is not overdone. In fact, there are actually not that many computer enhanced shots in the entire movie. Whatever moments there were had help from practical effects that helped to blur the lines between the different shots. The only times the movie uses CGI is when the dinosaurs’ are shown full body. When close-ups were needed, the filmmakers would use an animatronic puppet, or sometimes just a movable limb. It was a way of keeping old tricks useful while still leaving room for the new enhancements, and the result works spectacularly well. Filmmaker Walt Disney had a philosophy when using special effects in his movies that you could never use the same effects trick twice in a row between shots because it would spoil the illusion. You can see this idea play out in many of the amazing moments found in Mary Poppins (1964), a groundbreaking film of it’s own. Like Jurassic Park, Mary Poppins mixes up the effects, helping to trick the eye from shot to shot. By doing this with the dinosaurs in Park, it made the CGI feel all the more real, because it would match perfectly with the real on set characters. It’s a balance that redefined visual effects, and sadly has not been replicated that much in the years since.

Jurassic Park has seen it’s share of sequels over the years, with the fourth and latest one, Jurassic World (2015) making it to theaters this week. And interestingly enough, each one features more and more CGI in them, and fewer practical effects. Some of them look nice, but why is it that none of these sequels have performed as well as their predecessor? It’s probably because none of them are as novel as the first one was, but another reason could be that the illusion is less impressive nowadays in a world inundated with CGI. Somehow a fully rendered CGI T-Rex attacking humans in a digitally shot, color-enhanced image in Jurassic World doesn’t have the same grittiness of a giant puppeteered T-Rex jaw smashing through a glass sun roof on a climate controlled sound-stage in Jurassic Park. Sometimes it helps to look old-fashioned. Some of the action may be impressive in Jurassic World, but you won’t get the same visceral reaction from the actors on screen that you got in the original. The reason why you believed actors like Sam Neill and Jeff Goldblum were in real danger is because they were reacting to full-sized recreations of the dinosaurs on stage. Chris Pratt may be a charming actor, but you feel less concern for his character in the movie when you know that all he’s acting opposite of is probably just a tennis ball on a stick. The original Jurassic Park made it’s CGI the glue that stitched together all the other effects, and that made the movie feel more complete. World has the benefit of having the best effects tools available to it, which is better than what The Lost World (1997) and Jurassic Park III (2001) had, but it still won’t have the same visceral power of the original, and that’s purely because it’s moved so far in one direction from where it started.

Hollywood in general has abandoned many of the old, traditional effects in favor of more CGI. Some of this has been for the better (does anyone really miss rear-projection?). But, too much can sometimes even hurt a movie. This is especially true when filmmakers, even very good ones, become too comfortable with the technique and use it as a shortcut in story-telling. George Lucas unfortunately became too enamored with the limitless potential of CGI, and used it to an almost absurd level in his Star Wars prequel trilogy. Yes, it looked pretty, but nearly every shot in the movie was digitally enhanced, and it only worked to highlight the artificiality of every scene as well as distract from the story. It gets annoying in certain parts where you can obviously tell that the actors are standing in front of a green screen in scenes that could have easily been shot on location. For Lucas, I’m sure part of the allure of making his movies this way was so that he didn’t have to deal with location shooting problems like climate and extras. But, what I think he failed to recognize is that part of the appeal of the original Star Wars was the fact that it was imperfect in spots, which made the special effects stand out that much more. By trying to make everything more glossy, he unfortunately made his world look fake, showing that CGI is not a fix-all for everything in cinema. And Lucas wasn’t alone in making this misjudgment. The Lord of the Rings was also another groundbreaking film series in terms of effects, and that was largely because director Peter Jackson applied an all of the above approach to making Middle Earth appear real, including extensive use of models and location shooting. When he set out to bring The Hobbit to the big screen, Jackson shifted to rely more heavily on CGI. While it doesn’t ruin the experience as a whole, one can’t help but miss the practical and intricate model work that was passed over this time around in favor of fully-CGI rendered locations. For both cases, more didn’t exactly equal better.

In recent years, it’s actually become more ground-breaking to avoid using CGI in the crafting of a movie. Some filmmakers like Christopher Nolan are making it part of their style to do as much as they can on set before having to use CGI for the final film. When you see something like the hallway fight scene in Inception (2010), you’re initial impression will probably be that CGI had to have been used for that moment at some point. That is until you’re blown away by the fact that nothing had been altered in that shot at all. It was accomplished with mounted cameras, a hydraulic gimble machine, and some well-trained actors; a low tech feat pioneered years back by Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and implemented to the next level by Nolan. That helps to make the scene feel all the more real on screen because it uses the camera and the set itself to create the illusion. Doing more on set has really become the way to make something big and epic once again in movies. We are more impressed nowadays by things that took their time to execute, and if the finished result is big enough, it will hold up against even the most complex of CGI effects. That’s why we’re seeing a come-back of sorts in recent years with regards to practical effects. It’s manifesting itself in little, predictable ways like using real stunt cars and pyro explosions in Furious 7 (2015) or in big ways like having Tom Cruise really hang off the side of a plane in midair in the upcoming Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation (2015). And J.J. Abrams is bringing practical effects back to the Star Wars franchise, which is step in the right direction as well.

Overall, a movie’s special effects are more or less tied to how well they work in service to everything else. Too much or too little CGI effects can spoil a picture, but not using it at all would also leave a movie in a bad position. Today, CGI is a necessary tool for practically every movie that makes it to the silver screen, even the smaller ones. A small indie film like Whiplash (2014) even needed the assistance of CGI when it had to visualize a car accident halfway through the movie. It all comes down to what the story needs, and nothing really more than that. Of course, there are boundless things that CGI can bring to life out of someone’s imagination, but sometimes a film is better served by taking the practical way when creating a special effect. Watch some of the behind the scenes material on the Lord of the Rings DVDs and tell me if it wasn’t better in some cases to use practical effects like models and forced perspective to enhance a scene instead of CGI. Sure, some creatures like Gollum and Smaug can only be brought to life through a computer, but it’s only after the animators had the guide of on set performances given by actors as talented as Andy Serkis and Benedict Cumberbatch. Plus, physically transformed actors in make-up come across more believably than their equivalents in CGI form, with exceptions (Davy Jones in the Pirates of the Caribbean series). I’d say restraint is the best practice in using CGI overall. As Dr. Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) says about technology run amok in Jurassic Park, “you were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that you never stopped to think if they should,” and the same truth can apply to how CGI has been used in Hollywood. It solves some problems, but it can also reduce the effectiveness of a story if mishandled. We’ve seen a lot of mediocre movies come out with wall to wall CGI effects recently, and much of the wonder that the technology once had has unfortunately worn off. Hopefully, good judgement on the filmmakers part will help to make visual effects an effective tool in the films of the future. The best illusions are always from those magicians who have something you never expected or seen up their sleeve.