With Halloween once again around the corner, it’s time again that we look at some of the season’s most notable icons. Monsters and ghouls are just as much associated with the Halloween holiday as Santa Claus is with Christmas. They are the easy go to ideas for costumes every year, and any visit to your local grocery store or mall at this time will almost always feature some kind of holiday branding featuring one or two of these characters. But, the interesting thing about the most famous of these iconic characters is that most of them were established out of the same unlikely source. Unlike Santa Claus, whose origins begin as a real life saint who has been re-imagined into the mythical figure we know today, or the Easter Bunny whose origins come out of folklore, Halloween’s gallery of rogues originated from the world of 19th century literature. Not only that, but many of them were created during the same literary movement; a pre-Victorian style emphasizing tales of the grim and unnatural known as Gothic. Some of the most notable authors of the era all contributed to this movement, and created some of the most memorable monsters that continue to remain popular to this day. Bram Stoker revolutionized the concept of vampirism with his now iconic villain Count Dracula; Robert Louis Stevenson gave us the psychological horror story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; H.G. Wells explored the spectral threat of the unseen with his Invisible Man; and even more earthbound authors like Charles Dickens would delve now and again into Gothic themes and characters. But, perhaps the most unlikely source of one of the Halloween season’s most iconic characters was young Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who brought the brutish Frankenstein monster to the world.

Mary Shelley was an unlikely Gothic author for her time, and one that no one could believe had a monster like Frankenstein within her imagination. The daughter of political philosopher William Godwin and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley seemed destined to always be an author in her own right. Her early writing primarily focused on recounting her travels across Europe, with her travelogues becoming valuable guides for her readers. But, on a trip to Switzerland in 1814, she heard stories from some of the locals of peculiar scientific experiments being conducted by some of the local lords; mostly harmless, but nevertheless mysterious. From this, Mary conceived the story of an experiment gone horribly wrong, creating a monster that would go on to haunt it’s creator. Over the next few years, she wrote out what would become the novel Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus (1818). It was one of the earliest works of the Gothic movement to become an immediate success, and many argue that it was one that was largely responsible for defining the genre as a whole. In fact, it’s often seen as a precursor to all the other monster characters that I mentioned before. So shocking it was when first published, that Mary Shelley had to remain anonymous as the author for quite some time. But, since then she has become a much celebrated figure in Gothic literature. Though her work was largely a product of it’s time, it has since captured the imagination of the world for nearly two centuries now, with it’s underlying themes of creation, identity, and male hubris. And these themes, along with the iconic image of the monster himself, naturally was too good to pass up once it reached Hollywood. In 1931, Universal Pictures delivered what is now one of the most celebrated adaptations of Shelley’s novel, as well as establishing the modern visual interpretation of the monster. In many ways, the movie Frankenstein is a whole different creature from the novel it’s based on, and yet it stays true to it’s Gothic origins and presents a whole new set of sub-textual meaning behind it. By comparing the novel and the movie, we can see some interesting results of how the myth has evolved over time.

“Think of it. The brain of a dead man waiting to live again in a body I made with my own hands.”

Universal’s Frankenstein, like the novel that inspired it, redefined it’s genre and influenced it for many years to come. Directed by James Whale, the movie took inspiration from German Expressionism that became popular during the late Silent Era of cinema, using shadows and light and off-kilter art direction to convey psychological terror to the audience. In addition, the movie also added a definite Hollywood spin on the story. Instead of the conflicted Victor Frankenstein of the novel, we get Dr. Henry Frankenstein, a traditional Hollywood protagonist (played by Colin Clive), seeking to resolve the problem he’s created in the most humane way possible. Hollywood’s Dr. Frankenstein is far different in that respect than the more weaselly Victor of the novel, who spends the entire story running away from his folly as opposed to resolving it. It’s a big difference between the two versions, but not necessarily one that ruins the story. The movie is attempting to do something different with the characters, giving the plot a much more rounded, good versus evil confrontation. Mary Shelley’s take on the characters delivers a much more socially conscious message, which is the to explore the arrogance of a male dominated society. Delivering on her own feminist ideals, some of which were quite radical for her time, Shelley points out that Victor’s own arrogance manifested itself in the creation of the monster and that his weakness is defined by the way that way he denies his own folly. Shelley was very critical of the Romantics of the Enlightenment movement, whom she believed carried this same kind of chauvinistic arrogance as Victor, believing that power through revolutionary thoughts and ideas could lead to a more utopian world. Shelley believed that such a notion was careless, because revolutionary concepts could also lead to disastrous results if reason and caution were left out. She saw this as a primarily male-centric shortcoming, and she used the misguided Victor as a representation of this.

“It’s moving. It’s alive. It’s alive. It’s ALIVE. Oh, in the name of God! Now I know what it feels like to be God!”

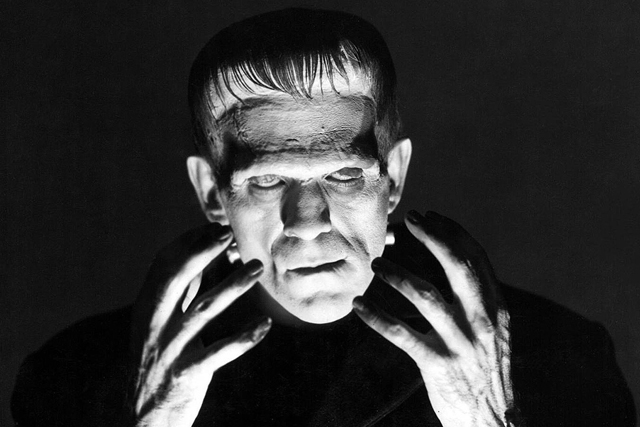

But the movie is less concerned with Victor/ Henry’s story and instead focuses much more on the monster itself. It’s easy to see why. Universal Pictures wanted to define it’s studios with a definitive horror icon, and Frankenstein fit that bill perfectly. Released at the same time as Dracula (1931), Hollywood finally defined the style of horror that would become a staple of the industry with these two iconic films. And like Bela Lugosi’s iconic performance as the Count, the portrayal of Frankenstein’s monster would become the standard for years to come. Boris Karloff portrayed the titular monster in a magnificent and surprisingly nuanced way. Instead of being just the lumbering giant that most other actors would’ve portrayed him as, Karloff brings a surprising amount of humanity to the creature, showing him to have childlike wonder about the world around him in addition to the carnal instincts that make him a menace. There’s a fantastic scene midway through the film where the monster encounters a little girl playing along the shore of a lake. Instinct tells him that the child is not a threat and the two play innocently for a moment, throwing flowers into the water. Of course, the uneducated monster doesn’t understand the difference between flowers and children yet, and he tosses the little girl into the water as part of this game, not knowing that he in fact killed her in the process. It’s a scene like that which shows the depths of the character perfectly; a monster guided by emotion rather than reason, doomed to be a monster because of the lack of humanity that his creator has shown to him. At the same time, Karloff does make the monster frightening on screen. When he strangles his victims, you really get a sense of the power of this creature and how it can be a menace.

The image of the creature is definitely something that the movie contributed to the character. In many ways, it’s true to Mary Shelley’s image, and yet very different. Shelley’s monster is indeed larger than the average man like the film version, but her creation is in many ways more grotesque. Her monster is made up of stitched up skin; yellow and translucent, and barely concealing the blood vessels and muscle tissue underneath. He also has yellow and red eyes, as well as long pitch black hair and black lips. It’s an image that immediately frightens away Victor after he brings the creature to life and makes him instantly regret his actions. The movie’s creature is obviously more refined due to Hollywood standards, but nevertheless distinctive. Huge and lumbering, he also is defined by his flat topped cranium as well as bolts sticking out of his neck. This particular image of the creature, as Boris Karloff portrayed him, has since become the definitive look of the creature, through all subsequent interpretations. Anytime you see Frankenstein represented today, it’s based off of this version, and not the yellow skinned monster of the novel. The green tinged skin color has also been given to the creature over the years, which may date back to behind the scenes documentation of Karloff’s make-up for the black and white film, or it could have come from one of the pop culture spin-offs that took inspiration from the character; the TV series The Munsters for example. Regardless, the image of the monster is the movie’s biggest contribution to the legacy of the story, but that in itself remains true to the theme of the story. The movie and the book are about the foolish attempts of human beings to take control of their own destinies and command nature itself, and the unexpected ways that the monster has changed over the years is proof that there is no certainty with regards to how our creations in life will withstand the test of time. Time has even given the name of Frankenstein over to the creature itself, and not to his misguided creator, something that I don’t think Shelley could’ve foreseen.

“Crazy am I? We’ll see whether I’m crazy or not.”

But, where the novel and the movie offer the most interesting contrast is in the different ways they deliver on the themes of identity and where one’s place is in the world. Shelley’s main emphasis with her story was looking at the role that man’s relationship with nature plays in the error of their ways. Her novel begins with a passage from John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost, which says, “Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay to mould me man? Did I solicit thee from darkness to promote me?” Along with the subtitle of The Modern Prometheus, Mary Shelley emphasizes that her story is all about asking why life exists with the creation not knowing the intentions of it’s creator. Victor, like Prometheus in Greek Mythology, defies the intended order of things just to see how his experiments will take hold, but never looks to what those consequences might be. The creature, on the other hand, embodies the chaotic results of creation with a will all it’s own. In the novel, the creature tries to find his own way in the world, separated from his absent creator. He learns to speak and read all on his own, observing other humans from afar, and yet cannot make use of any of it because of his unnatural existence that makes him a monster to everyone else. When he confronts Victor in the novel, he says that he’s the “Adam of you design,” referring back to the biblical first man, whose life is also recounted in Milton’s Paradise Lost. It’s a critical examination of the conflict between man and God, with the creature not understanding why Victor gave him nothing but life. Every useful thing he has is wasted because there was nothing to guide him towards a human existence. As a result, the creature seeks nothing more than to destroy his creator, unless he gives him more of a natural existence, namely, to repeat the experiment again so that he can have a mate. By refusing to repeat his past folly, the monster than haunts Victor, chasing him across multiple borders and even far North into the Arctic. Like his literary predecessors, Victor attempts to play the role of God, and is undone by his own creation.

The movie on the other hand deals with identity in a different way. The creature never quite grows out of his instinctual brutality, but this too is indicative of the neglect of his creator. But, what James Whale emphasizes in his movie is a sense of the creature becoming a victim of his own status of an outsider. Though it’s hard to say if Whale purposefully changed the story to suit this theme, but I feel like there was more than a little personal investment that the filmmaker put into the portrayal of the character in his story. James Whale was one of the first openly homosexual filmmakers working in Hollywood, and it was something he struggled with for most of his life, professionally and personally. His final tortuous years led to his untimely suicide, which were both dramatized in the film Gods and Monsters (1998), featuring Ian McKellan as Whale. Though still closeted at the time, I believe that some of Whale’s own struggles manifested their way onto the screen with the way that the creature is hunted down in the movie. Here you have a character who is shunned, condemned, and ultimately hunted down for merely being who he is. It’s only the innocent and un-corrupted that give him any bit of compassion, like the girl playing with her flowers. Albeit, it’s a bit harsh for someone to equate their own sexuality with the manifestation of a monster, but what I think Whale wanted to emphasize with his movie was how reacting to the monster also created a monstrous effect in society as a whole. The movie concludes with the creature cornered in a decrepit old windmill, torched alive by angry villagers seeking to destroy him. This plays into a fear that I’m sure James Whale probably had himself; being cornered by angry mobs of people who saw what he was as monstrous too. The only reason that the monster acts the way he does is because of the mistreatment that’s been directed his own way; a misfit whose only crime is living. I think that’s why the role of the creature is much more emphasized in Whale’s film, because it the character appealed far more to the issues that were important to him. In Whale’s world, a lack of identity makes you just as much of a victim as it does a monster, and sometimes society as a whole can be the true monster.

“You have created a monster, and it will destroy you!”

Both the novel and the movie are very different creatures, but both are exceptional in their own right. Mary Shelley’s novel defined the Gothic style and would go on to inspire all sorts of classics in the genre. It could even be said that Frankenstein invented science fiction, because it was the first popular story written during the age of scientific discovery during the early 19th Enlightenment period. All the wonders of the pre-Victorian and late-Victorian age were developed within the shadow of Frankenstein, and her novel proved to be an effective cautionary tale of taking experimentation too far and not dealing with the consequences of unchecked industrialization. The movie, likewise, would go on to influence it’s own genre, becoming the definitive Hollywood monster movie. Both also offer interesting insights into human behavior and how man’s relationship to nature is a volatile one. Shelley’s novel gives an interesting insight into man’s own arrogance leads to self-destructive ends, while Whale’s movie establishes the interesting idea that intolerance itself creates an endless circle of violence, some of which leads to own own self-destruction. Regardless of the different interpretations that each made, they have nevertheless made an unexpected icon out of it’s unforgettable monster. Boris Karloff’s performance as the monster is especially a great one, and it’s because of him that I think the story continues to remain popular to this day. It’s interesting to think that the oldest of these Halloween season icons is also the one who feels the most modern. It’s a testament to the effectiveness of Mary Shelley’s imagination, where she was able to dream up a monster who would withstand the test of time and in a way, become timeless. Whether he’s meeting his bride for the first time, or scaring off Abbot and Costello and Scooby Doo, or even being the mascot of a breakfast cereal, Frankenstein is an indispensable icon of the Halloween season, and one one whose resurrection will continue again and again.

“Whose life was one of brutality, violence, and murder.”