Up until now, the film exhibitions that I’ve reported on for this site have mainly focused on one or two things; mainly film history or film art, or a combination of both. I have also taken a look at festivals that give a look at the future of film-making. But, this week, I decided to take a look at another new exhibit in my area that focuses not on film history or art, but rather the science of film-making. Taking advantage of my Los Angeles residence, I took a short trip downtown to the California Science Center located in Exposition Park (across from the University of Southern California campus). Started in October of last year and running through April this year, the scientific institution is showcasing a special exhibit dedicated to the technological breakthroughs accomplished in the movies by Pixar. Created in collaboration with Pixar themselves, the exhibit doesn’t necessarily showcase Pixar related artifacts, but instead offers up hands on demonstrations about how their movies get made. It’s little different than what you would usually find in Science Centers across the country, where every exhibit is meant for learning and play. But, when given to a film-making giant like Pixar, you get that extra special presentation and polish throughout. The exhibit is worth checking out if you are an especially ardent fan of Pixar films (myself included), because it really gives you a deeper understanding of all the rigorous hard work that goes into the making of each one. Some of it is pretty mind-boggling too. It’s also worth checking out for anyone who is just interested in the mechanics behind film-making, even when it’s entirely done within the computer. So, with a healthy sampling of pictures taken by me from inside the exhibit, let’s take a look at “The Science Behind Pixar” at the California Science Center.

You first enter the exhibit through a modest doorway and enter a tiny theater for a short 5-minute introduction. The video is basically a tour of the Pixar Studios in Emeryville, California, with two of the staff artists leading us through the many different departments. In the video we meet two key founders of Pixar, John Lasseter and Ed Catmull, both of whom represent the creative drive behind Pixar and the scientific innovation drive; the two primary factors that make Pixar who they are. Through each department shown, we get a glimpse of how every person at Pixar is encouraged to push the boundaries of what can be done in their field and constantly push the medium forward. But apart from stating the mission statement behind Pixar, the video also gives those of us that about to enter the exhibit a good primer about what we are going to see. Essentially, the making of Pixar movies boils down to several distinct stages; story and concept, design, modeling, rigging, surfaces, sets & camera, lighting, simulation, animation, and finally rendering. Each of these departments ultimately make up the exhibits that we will find in the next room. After the conclusion of the video, which includes a recorded etiquette spiel from Pixar director Bob Peterson, voicing two of his more notable characters from Pixar movies (Mr. Ray from Finding Nemo and Roz from Monsters Inc.), the doors open and we are welcomed into the exhibit floor.

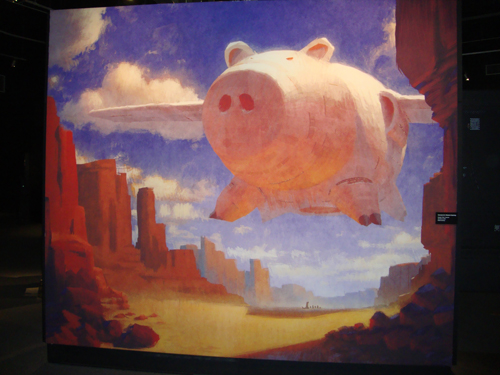

The room is loosely laid out for everyone to choose their own path through the exhibit. Of course, every section is spotlighted with large overhead signage, and in a few cases, also by large, full sized figures of some famous Pixar characters. Not only do they give this gallery a pleasing aesthetic, but the figures are also popular photo opportunities for guests. The exhibit is broken up into two rooms, the first concentrating on the more scientific elements of Pixar’s work. Story and Concept doesn’t get it’s own section, because I think that it was mainly laid out in the introduction. It’s basically where all movies start; an idea. Pixar takes their ideas and then moves them over to Design, where the first artistic representations of those ideas help to shape what the movie will ultimately look like. Many of those images are then turned into storyboards, which are then filmed together to create a blueprint for the movie as a whole. It is from Design that the movie finally moves to construction, and that’s where the science behind Pixar finally starts to kick in. There is no section dedicated to Design either, but several recreations of original art are littered throughout the gallery, just to give us a sense of the long journey it takes to bring an idea and make it a reality in three dimensions. So, going in order of production, let’s look at each section individually.

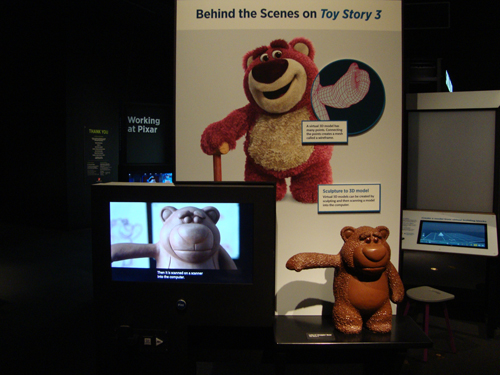

After Design, the next stage of production is modeling. This is where the artists take what’s drawn on the page and crafts a 3D representation of it which will then be animated in the computer. This starts with sculpting, which can be accomplished in two different ways. Some things can be sculpted by scratch within an axis based construction within the computer, but Pixar has also achieved the same with scanning hand made sculptures within the computer. They have sculptors create Maquettes, which is primarily used for character models. The maquettes are small sculptures made out of clay (a practice that goes all the way back to early Disney animation) and helps to give the artist a full view of what the final appearance of the character will be on all sides. The maquette is then scanned in high resolution, which then creates a fully, three-dimensional sculpture within the computer. But, this is only meant to finalize the model. Making it move is a whole other step. The section focuses mainly on the Toy Story films, with maquette recreations of Buzz Lightyear and Lotso from Toy Story 3 (2010) displayed for a hands on interaction. There is however a display case featuring real maquettes on loan from Pixar’s archive, which includes Remy from Ratatouille (2007), Russell from Up (2009) and Heimlich from A Bug’s Life (1998). After learning about the way these characters are built, we then move over to see how they are given movement.

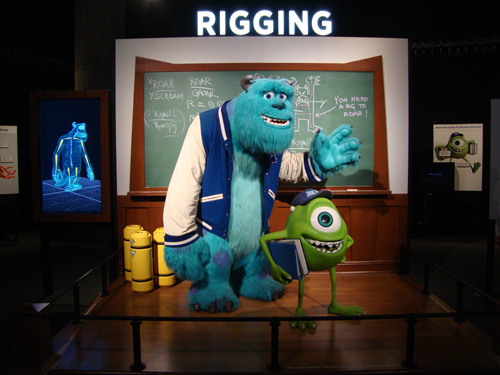

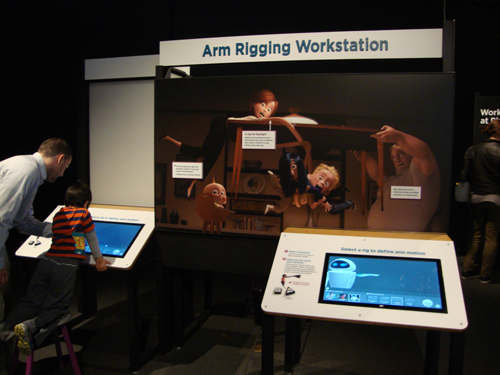

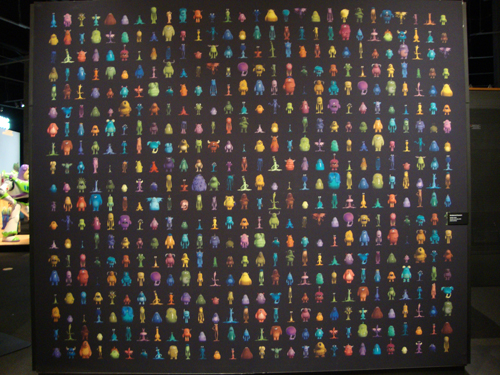

Rigging is the next section, with Monsters Inc. (2001) and Monsters University (2013) being the primary focus here. The Rigging department is responsible for taking the models sculpted in the Modeling department and giving them an internal skeleton that will help it move. It is here that we find the first of many demonstration stations littered throughout the exhibit. At each station, guests are able to work with a computer simulation of the actual programming that Pixar artists use. In the Rigging demonstration, we are shown how every character is built up with a series of rigid arms that are ultimately given movement through joints. Much like how joints work inside our own bodies, these virtual joints not only create movement but also flexibility. The demonstration allows us to select between different numbers of joints, and shows us how the greater number of joints we add, the greater freedom of movement we are allowed for the model, and it’s shown through a difference between one rigid joint and eight floppy joints. There is also a separate station that shows the rigging done on character faces, which itself is a tricky science. The station gives us the opportunity to change the expressions on the face of Jessie from Toy Story, and believe me, it’s not as simple as that sounds. It’s a nice, easy to understand demonstration of how Pixar creates the mechanics behind their characters. Essentially this where they put the strings on their puppets, which can end up being upwards of many hundreds of strings, depending on the character.

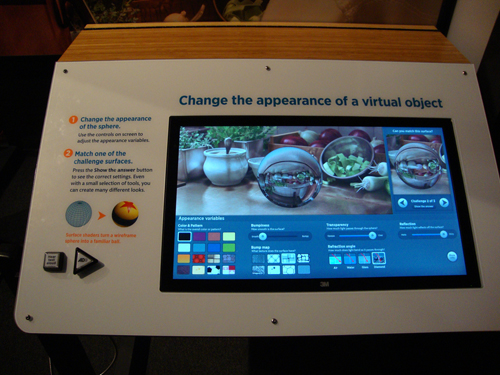

Next up is Surfaces. This is where character models go to receive their final dressing. Up until now, characters are just three dimensional, featureless objects that have an internal skeleton that will help them move. It’s in Surfaces where they go from smooth and featureless, to textured and life-like. Crafting the skins of an object is just as difficult as crafting the actual model, because you have to take into account things like the roughness of the skin, it’s transparency as well as it’s reflective-ness. The Cars movies are spotlighted here, mainly because those films offered up an especially hard challenge for the Pixar artists. With a cast full of anthropomorphic cars, the filmmakers had to take into special account the different properties that real cars can have and apply those to the characters. This varied from Lightning McQueen’s super reflective surface to Mater’s very rusted surface. Both of those skin surfaces react to their environment in different ways, so that’s why special care was devoted to making them look as natural as possible. The big demonstration station here allows us to change the appearance of different engine hoods, combining a variety of different things like sparkling paint, logos, and rust to the surface. Another station let’s play with the texture of objects, showing how fine details add to the overall life like image of what we’ll see on the screen. Essentially, this is the final stage of character modeling, and the last stage of crafting all the pieces needed for the film. What follows is where the actual art of film-making begins.

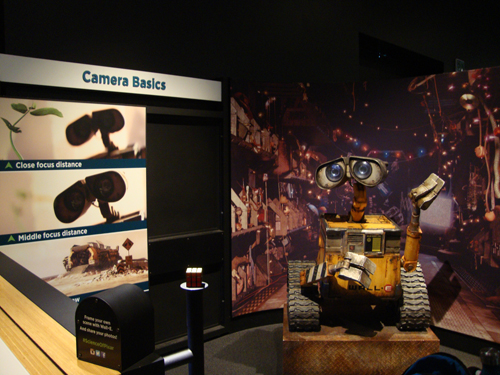

The next section is Sets & Camera, and it is spotlighted by a stunning recreation of Ant Island from A Bug’s Life. The level of detail on this model is astounding, right down to the little “altar of offering” that is a focal point in the film. The best thing is that there is a crawl space underneath that has little glass domes in the middle that allows you to look at the model from a bug’s point of view. Unfortunately, the crawl space is tiny, and is meant more for younger visitors. Still, if you don’t mind squatting through a tight space, it’s a neat view. The model also includes live cameras that you can shift up and down. This is obviously meant to represent how camera perspective is used to tell a story; in this case, viewing the world from the point of view of a bug. But, this section also demonstrates the amazing work that goes into composing the shot of each movie. So much detail is put into the sets of Pixar movies, and most of it will be unseen by the viewer, and this is mainly because they need to apply the same rules to virtual film-making that apply to actual film-making. And that means never having anything in frame look out of place. The remarkable thing about computer animation is that everything is done from scratch; including set dressing down to the smallest detail. But, even with the limitless freedom computer generated imagery can give us, Pixar still applies the same rules to film-making from the real world into their virtual one. The camera that doesn’t exists still has to act like a real one; like it’s there rolling on a set. That’s why they build programming to recreate camera effects like shallow focus, depth of field, wide angle distortion, etc. These are all demonstrated on a nice full size replica of the robot Wall-E, with a live camera demonstrating all the same properties. This section in particular really drives home how science not only influences the construction of computer animation, but also the basic storytelling tools of film-making.

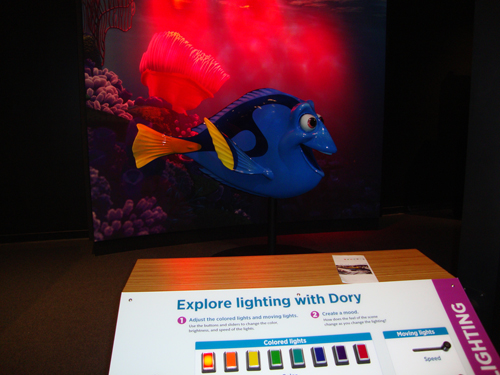

Next up is Lighting. This is a stage where Pixar artists must take everything that’s been built for each scene, and give it lighting that makes it look natural and film like. Just like everything else, light sources are virtually created in the computer, and can be dimmed or brightened depending on the necessities of story. Lighting influences mood, so it becomes an instrumental part of the storytelling of a film. For this section, the exhibit highlights Finding Dory, because it’s the film that represented the biggest challenge to the Pixar artists in this respect. Not only did they have to create natural looking light for each scene, but they had to also add the extra prism of lighting through virtual water. Needless to say, a lot of research went into seeing how light dispersion works underwater and that’s demonstrated very well in this exhibit. Spotlighted in the middle is a nice demonstration on a figure of Dory. Here, you can change the brightness of the light, as well as the color, and it shows how much those changes change the appearance of the character, how it sets the mood, as well as the environment around Dory. There’s also another neat station that allows you to set up the lighting in a scale model of the living room from Carl and Ellie Fredrickson’s home in Up. It demonstrates how source lighting affects a scene in the same set in many different ways. Plus, it’s just neat to look at the house from up recreated in miniature with an interactive element. At this point, this is where the film will start to take on it’s final look, but not before some final tinkering.

Next is Simulation. This is where they tune everything built up to now to react to it’s environment in a natural, realistic way. This is usually everything that is attached to their models and is meant to act automatically without having to be directed with it’s own animation. This can be everything from the clothing that characters wear, to leaves on trees, to even flowing water. Pixar’s Brave is spotlighted here because of one particular element that they had to innovate with in order to make it work on film; that being Princess Merida’s wild, untamed head of hair. The hair on her head had to act like normal hair would, including having the same springiness to the curls as you would see on a real person. That’s difficult to simulate in the computer, so what this demonstration shows you is how they create an internal structure just for Merida’s hair and allowed it to move naturally as the character moves, without having to animate it separately. The demonstration also showed how they applied this same programming to clothing, running water, as well as large crowds. It’s surprising how much automation is put into things that you wouldn’t expect. There is also a neat demonstration station nearby, where the exhibit had constructed a tilting see-saw that runs real water down a slide, alongside round pellets and digital recreations of animated water, just to show the different stages of how they get virtual water to act like the real thing and how they can make it an automatic thing in the computer. It’s this fine tuning that really shows the level of detail that Pixar puts into every frame.

From there, we move out of the first room and out into the last, which is on the outside terrace looking over the lobby of the Science Center. Here, we see all the science mechanics come together to create the story itself. And this begins with Animation. Spotlighted by Brad Bird’s classic The Incredibles (2004), we see how all the elements of Modeling, Rigging, and Simulation is put into motion to allow the digital puppets to finally act. This is where the illusion of life truly happens. The demonstration station has several scenes from the movie playing on screens above, and in front are wheels that when turned slows down the image rate of the playback. The slower the turn, the slower the frame rate. Essentially this is meant to show how each frame of character movement reveals the mechanics of what we have just learned in the previous room, and how they all work together to reveal character in the models. It’s fitting that a life size figure of fashion designer Edna Mode stands nearby, given how much each frame of a movie, especially Pixar ones, require so much work in their design. Nearby, there’s a neat little demonstration activity that allows quest to craft a short stop motion film, using a prop Luxo Lamp Jr. (Pixar’s mascot) as their subject. You can move the Luxo Jr. along a wall, posing anyway you want, and snap a photo from a stationary camera, and through the magic of film, you can create a short second of animation right there before you. It’s of course meant to show how many frames a film needs to fill up a second of screentime, and given the lengths of these films, the incredible work it takes to build just one frame.

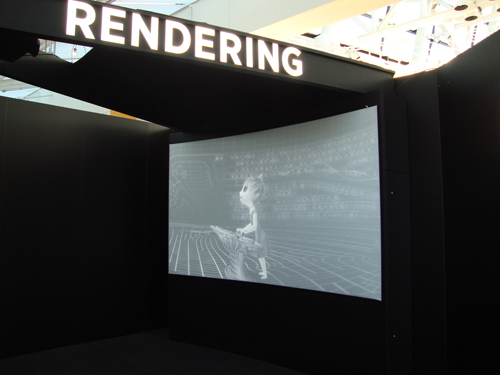

From here we enter a rotunda that illustrates all the previous stages of development needed for Pixar’s films, all shown simultaneously in a select scene from 2015’s Inside Out. It’s a neat showcase to see all the stages shown together and how many steps it takes to get to that final step in computer animation; Rendering. This is the animation equivalent of picture locking, but it’s a far more complicated step that is incredibly time consuming. Basically this is the step where everything we’ve seen up to date is run into Pixar’s server to create a full, seamless high definition image that will then be used as their original source image for distribution. It removes all of the imperfections, locks all the animation movements down, and smooths out all of the aliasing pixels to make the image flawless. And the staggering thing you learn from this section is that it takes 36 hours to render just one frame. Considering how long some of these movies are, it could take up to close to half a million frames at least to make up a single movie. So, from this station, we learn that Pixar has hundreds of computers at their offices that do nothing but render images, and these computers run round the clock endlessly in order to get a movie completed on time. Not only that, but some are rendering multiple projects at the same time. The station here demonstrates the final render process, showing how each image is constructed from it’s bare wires to it’s final life like image. From here, you really get the sense of how science comes together to create beautiful imagery, and how that has become Pixar’s hallmark.

After this, in typical Disney fashion, we exit into the gift shop, with Toy Story’s Woody smiling back as we walk out. Overall, it’s an impressive way of demonstrating to the average person how Pixar movies are made. Naturally, with this being a Science museum, the focus is on the many scientific breakthroughs Pixar has made in the field of computer animation, and how they’ve used all of that to create this impressive filmography. But, at the same time, the exhibit shows that none of these breakthroughs would’ve meant anything had there not been stories worth telling that supported them. One of the best elements of this exhibition are the little video stations found in each section, where it allows you to listen to individual artists in each department tell their story, and how they brought their knowledge of science and discovery into the work they do. It’s that mixing together of scientific innovation and creative storytelling that has always been at the heart of Pixar’s soul, and it’s represented fully by the people who work there. This exhibit not only let’s you share in the warm memories of seeing all these again, but also understanding the mechanics that went into them. Back in the 1950’s, Walt Disney showcased on his Disneyland television series several shows that actually demonstrated the craft of animation, and that in turn inspired future artists to want to do the same thing, and out of this arose the next generation of inspired animator, of which includes many Pixar employees. My hope is that an exhibit like this creates that same kind of fascination for younger audiences, and inspires them to take an interest not just in learning about film-making, but in the sciences as well. The exhibit runs through April, so if you are in Los Angeles before then, it’s worth a look. Young or old, you’ll find a lot of joy in seeing art and science work together in such a beautiful way.

https://californiasciencecenter.org/exhibits/the-science-behind-pixar-exhibition