The art-form of animation has many different faces, but it’s evolution over the years has heralded many different eras with the medium as well. For the longest time, when people thought of animation, the thing that would pop into their mind was the traditional hand drawn, painted cel form of animation. This was mainly because the people responsible for bringing animation into mainstream popularity were the people at the Walt Disney Company as well as those at Warner Brothers with their line of Looney Tunes shorts. And for many years, they set the standard for what the public would accept as the look of hand drawn animation. While the medium was pushed forward by leaps and bounds made by the artists at both studios, the success they saw also in a way stifled any artistic deviation within animation. Disney stuck mostly with making safe, family-friendly fare while Warner Brothers stuck with cartoonish slapstick, and since they saw continued success because of this, other up and coming studios never strayed too far from the formula. To really take the medium further into more daring territory and do something completely different in animation, you usually had to work independently like animators Richard Williams and Ralph Bakshi did, and those guys were lucky to see even one of their movies turn a profit. After a tough time for animation in the 70’s and 80’s, the Disney studio came roaring back with an era now known as the Disney Renaissance. Again, with one studio dictating the popularity of the art-form, there was less enthusiasm for deviating from the formula in animation, and the business of animation became less about finding one’s own voice and instead more like seeing what Disney was doing right and trying to copy it. That unfortunately led to many competitors creating what you could call Disney-lite animated films, which were movies trying way to hard to be like a Disney movie but lacking that one thing that made Disney stand apart. In turn, this only drove down the different brands of these animation studios, as audiences lost their trust in them. Sadly this happened at the worst possible time for that one movie that indeed stood out from the rest and was destined to become a classic on it’s own; The Iron Giant (1999).

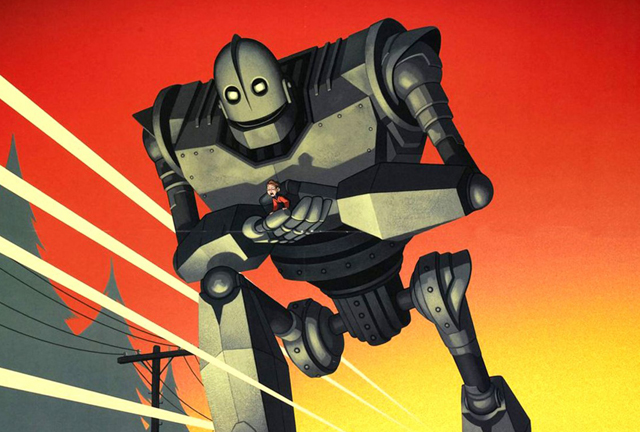

If you could point to an animated movie that came from outside the Disney Studios that can be considered among the best of all time, Iron Giant would be that movie. In fact, when I compiled my own list of the best non-Disney or Pixar animated films as seen here, this was the one that I put at the very top. This movie is an absolute masterpiece of animation, and the thing that is great about it is that it can stand perfectly on it’s own without ever having to be compared to another film in the Disney canon. It is stylistically very different, taking more of it’s inspiration from Cold War era character designs as well as using a Norman Rockwell style grounded approach to the environments. In terms of narrative, it also deviates heavily from Disney. It’s not a fairy tale, but rather science fiction. There are no talking animals, no songs, no magical happy ever after. It’s about real people in a real town who are suddenly introduced to a very massive visitor from outer space. And it even deals with some very heavy subjects like death, social paranoia, war, and being ostracized for being different in small town America. But at the same time, the movie is not the anti-Disney movie. Classic Disney from the Golden Age of the 1950’s also gives the movie some inspiration, particularly in the color palette. And it’s message of friendship between the unlikeliest of companions is something that feels like it could have appealed to even Uncle Walt himself. The movie is rightly seen as a masterpiece today, but believe it or not, The Iron Giant was in it’s time one of the biggest box office flops of it’s day. It performed so badly in fact that the animation studio responsible for it, Warner Brothers Feature Animation, closed it’s doors soon after. Apart from it’s unusual road to becoming reality, the really fascinating story about The Iron Giant is how it managed to stay in people’s consciousness and eventually find it’s audience, sometimes even many years later. It’s all a testament to the fact that great movies never die; they just get reborn.

The beginnings of The Iron Giant stem all the way back to the very Cold War era setting that is seen in the film. The original children’s book on which the movie is based called “The Iron Man,” was written by author and poet Ted Hughes. His book is a simple tale of friendship that is built around the bond between a boy and the living war machine that he befriends. Within the tale, Hughes delivers a powerful yet subtle anti-war message, essentially exploring the idea of what would happen if a “gun” decided it didn’t want to be a “gun.” It’s in choosing the path of refusing one’s destructive programming in favor of a pacifist life that defines the Giant’s story and it’s that message that became so appealing to filmmakers interested in adapting the story. You can see echos of the tale in movies like E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) and Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1992), but it wasn’t until a rising star in the field of animation named Brad Bird came across it that the book was finally going to see it’s jump to the big screen. Bird, a contemporary of many now legendary Disney animators, managed to find his footing in animation outside the “house of mouse,” working on shows like The Simpsons and Amazing Stories instead. Despite calls from Disney to come over and join their team, Bird instead set up home in the newly formed Feature Animation unit of Warner Brothers. Warners was renowned for their Looney Tunes shorts, but until the 90’s they had largely stayed away from making feature films like Disney. But, with the Disney Renaissance becoming a monumental success, Warners quickly cobbled together their own studio to take advantage of this new trend that was making a mint for their competitor. Their first feature would be the very Disney-esque Quest For Camelot (1998), with Bird’s directorial debut coming up second right after it. Though someone of Bird’s talent was capable of tackling any project, it’s still logical that The Iron Giant would be the thing that he would tackle first as a director.

For one thing, the Cold War era setting is something of a favorite for the director. If you look through all of Brad Bird’s filmography, there is a clear heavy influence of the retro graphic style of the 1950’s throughout his films. It’s there in The Incredibles movies as well as the movie Tomorrowland (2015), which practically is a time capsule of a different era in itself. No doubt he wanted to explore that era graphically, but the movie’s powerful story of friendship no doubt played a big part in bringing him to the project. Working with a script adaptation from Tim McCanlies, Bird’s approach to Ted Hughes original book is remarkably faithful, albeit it changes the original English setting to a distinctly American one, and it also removes the giant alien bat that appears in the original book’s climax. No doubt the focus was put on getting the relationship right between the Giant and the young boy, and that’s where the movie really soars as a narrative. There is nothing forced or schmaltzy about the bond that they form. When we meet the young boy named Hogarth Hughes (voiced by Eli Marienthal) he already has an interest in strange and out there ideas, so he would respond to meeting a 50 foot tall robot differently than a more closed minded individual. The Giant himself is also wonderfully naive about his true nature, and the movie has a lot of fun showing him forgetting just how big and powerful he really is; acting like a giant, metal puppy dog. There’s no dobut that the animated medium was the only way to effectively tell this kind of story, because through animation, you could best convey the wide range of emotions seen in the Giant’s transformation from monster, to playmate, to ultimately savior. But, it’s also a testament to Brad Bird as a director that he grounds the movie in a sense of authenticity as well. Even while the extraordinary is happening throughout the story, it never feels cartoonish nor fanciful. And in that sense, Bird made an animated feature that indeed felt unlike anything else at the time.

Unfortunately, the foundation on which the film was going into theaters standing upon was far from solid. The Disney Renaissance was already beginning to wane in it’s later years, with modest successes like Mulan (1998) and Tarzan (1999) being overshadowed by the disappointing receptions of Pocahontas (1995) and Hercules (1997). Plus, all the copycat films trying to follow the Disney formula like Fox’s The Swan Princess (1995) and Don Bluth’s Anastasia (1997) all under-performed and made audiences grow weary of the animation medium as a whole. At the same time, computer animation was growing into a bigger threat with every new release, with Pixar’s Toy Story (1995) and A Bug’s Life (1998) both becoming huge box office hits. Naturally the timing was terrible for Warner Brothers who came too late into the came. Quest for Camelot was panned by critics, being labeled as a cheap Disney knock off, which did not put the new studio on solid footing. A lot of pressure was resting on The Iron Giant to pick up the ball after Camelot had dropped it. The movie did, thankfully, receive widespread praise from critics, but that didn’t help it enough. The movie was unfortunately released the same mid-August weekend as M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense (1999), which of course became a box office phenomenon. After being buried in theaters, the movie only made a quarter of it’s original budget back, which only accelerated the downfall of Warner’s animation studio. The studio cut it’s staff after The Iron Giant’s initial release and left only a handful to finish their next and last feature, the animation/ live action hybrid Osmosis Jones (2001). Brad Bird left Warners soon after and made his way over to Pixar, where he was able to get a little pet project off the ground called The Incredibles (2004), which would of course help turn him into a household name thereafter. It’s just unfortunate that once a studio finally had something special to set it apart in a Disney driven world, it was far too late to undo all the bad mistakes of the past.

But, like all great movies, the film didn’t fade into obscurity. Those film critics who heralded the film in it’s initial release continued to sign it’s praises long after. Eventually, word of mouth carried the movie along, and once it reached home video, it sold far better than Warner Brothers had expected. After that, the Cartoon Network licensed the movie for airing on their channel, and again, it enjoyed solid viewership every time it played. With solid home entertainment numbers coming in, the movie no longer appeared to be the embarrassment that Warner Brothers had thought they had before. Now, it was a modest success, albeit now at a time when Warner Brothers no longer had the infrastructure in place to follow up this success with. It didn’t matter at the time that they no longer were making animated movies, since Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings were already making them plenty of money. But, The Iron Giant did become a clear sign that they could make an animated movie that could rival those made by Disney in terms of quality, if not box office success. The fact that of all the animated movies released in the year 1999, including Tarzan, South Park, and Toy Story 2, The Iron Giant is the one that celebrated the most 20 years later is really a testament to it’s lasting staying power. Eventually, Warner Brothers would reopen their animation studios, albeit for computer animation instead of hand drawn, and make celebrated films like Happy Feet (2006) and The Lego Movie (2014) out of it. The Iron Giant may not have directly re-convinced the studio to invest in the medium once again, but it probably helped convince Warners that they had a place in the history of animation worth preserving.

It is pretty remarkable to see how widespread the legacy of The Iron Giant has gone beyond the film’s place at Warner Brothers animation itself. It’s been referenced in many different films, most prominently in Steven Spielberg’s recent big budget extravaganza Ready Player One (2018). The Iron Giant himself gets an extended cameo within the movie, even participating in the movie’s climatic battle scene. It’s also interesting how it’s managed to influence the career of the actor who got to bring voice to the Giant himself. Vin Diesel won the part over some long established veterans in voice acting, including legendary Transformers alum like Peter Cullen and Frank Welker, and it was now doubt due to Diesel’s natural low bass voice. Diesel, a relative newcomer at the time, brings so much humanity into the role, and remarkably does so with a limited vocabulary. When your character says only a handful of lines, it takes talent to find the personality underneath those few words, and Diesel somehow managed to do it. Much like how Karloff found the humanity in Frankenstein’s simple way of speaking, Diesel managed to create an endearing character with a few grunts and growls. But where his performance really shines is in the closing moments of the movie, which is the film’s most famous scene. When the film’s villain recklessly launches a nuclear weapon at the town where Hogarth and the Giant live, the Iron Giant consciously self-sacrifices himself to save everyone. Before this, Hogarth has introduced the Giant to comic book icons, and in particular Superman, which the Giant takes a liking to. As the Giant nears his fateful impact with the warhead, Hogarth’s words ring in his ear, “You can choose to be whatever you want to be,” meaning he didn’t need to be the weapon he was built as, and in a perfectly delivered line reading from Vin Diesel, the Giant realizes who he desires to be in that moment; “Superman.” That moment still gives people goosebumps to this day in it’s absolutely perfect execution of uplifting pathos. It wouldn’t surprise me that this role would one day lead to Vin Diesel delivering such an endearing presence through a simple reading of the words “I am Groot.”

There’s no doubt about it; The Iron Giant is an all time classic and one that thankfully has matured well over these last 20 years since it’s original premiere. It’s a shame that it’s blundered original release only accelerated the further downfall of traditional animation as a fixture within the industry, but it’s not a reflection of the quality of the film itself, obviously. Traditional animation sadly had no answer to the groundswell that was computer animation, which more or less took everything over in the new century. It’s only thanks to the fond memories that we have for The Iron Giant and the Disney Renaissance that traditional animation still has a presence in our culture today. The Iron Giant even shows that there is a place for films made outside of Disney that can stand shoulder to shoulder with the best of their canon. The Iron Giant has so much to offer for those who are looking for something different, or just for something that honors the medium of traditional animation with every lovingly crafted frame. Brad Bird clearly put a lot of heart into the film, both as a fan of the story and of animation itself. It’s no mistake that Hogarth’s surname is a nod to the original author of the book, and there is a wonderful little Easter egg for animation buffs when we meet the two elderly train conductors, based on real life Disney animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston (who also provided their own voices too). But what’s probably most important about The Iron Giant’s 20 year legacy is that it’s universal themes feel even more relevant today. It’s all about a character built to be destructive choosing to reject those instincts and learning to be a good person. The Giant chooses not to be a gun, which is the fundamental message of Ted Hughes original narrative. In a world we live in now, when it’s become so easy to act out in destructive ways as weapons of division and destruction are more widely available to us, it’s all the more inspiring to see a literal weapon of war making the conscious decision to reject his programming and choose to be better than all that. He chooses to be a hero; he chooses to be Superman. And that’s what makes The Iron Giant more than just a great cartoon; it’s a great and profound movie in general, and one that will remain a Giant in cinema for all time.