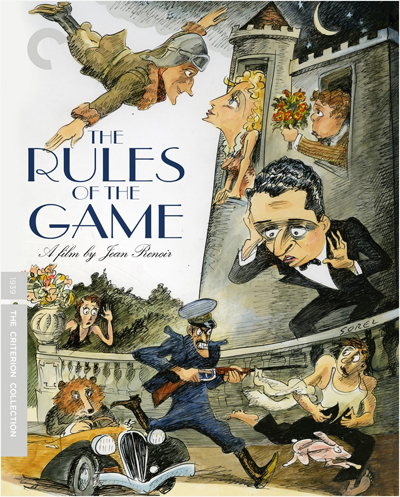

It’s strange when you see something thought to be old fashioned and classical all of a sudden become the rage once again. I often think about that when I look at the series Downton Abbey. The English made television series is a relatively simple show about relations between members of the British aristocracy and the working class staff that labor in their opulent manor house. Period dramas such as these tend to be a niche genre with a limited audience pull, but to many people’s surprise, Downton Abbey became a phenomenon; not just in it’s native country but across the world too. I myself got caught up in the hype too and became an ardent viewer of the show over it’s six season run. There was just something so perfectly fine tuned about the show that made it incredibly appealing, which probably is attributed to the excellent ensemble cast as well as the razor sharp wittiness of show creator and head writer Julian Fellowes. But Downton Abbey is by no means a fluke either. It follows in a long tradition of period dramas that focus on the class differences that manifest within the walls of stately manors. You see it quite a lot in the films of Merchant Ivory, as well as in a series that served as the precursor to Downton Abbey called Upstairs Downtairs, which aired on the BBC (and on PBS here in the States) in the late 1970’s. Upstairs Downstairs even gave this particular sub genre it’s commonly used nickname. Julian Fellowes also won an Oscar for writing a movie that many consider now his Downton trial run, called Gosford Park (2001), directed by Robert Altman. But what may surprise many people is that this film tradition didn’t begin in “Merry old England,” like you would assume, but rather in pre-War France. The Upstairs/Downstairs genre of film can arguably be traced back to the Jean Renoir classic, The Rules of the Game (1939, Spine #216) which also has been graced with a special edition via the Criterion Collection. Many of the standards of the genre that we still see used today were written in this original satirical dramedy, and surprisingly, for it’s time, these weren’t a stroll back into a bygone era, but in fact a product of it’s time.

Jean Renoir, the son of famed impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, holds a very special place in the Criterion library. Not only did they choose to spotlight his work early on in their home video releases, but they even launched their line with a Renoir flick. Renoir’s legendary anti-war drama, Grand Illusion (1937, #1) was the very first ever film released under the criterion label on DVD. It’s understandable that this was the movie that Criterion chose to launch themselves onto the DVD format with, because it’s often cited by many as the greatest film ever made; at least in art house circle. Orson Welles even cited it as the highest achievement in film-making, and this is coming from the guy who made Citizen Kane (1941), which itself is held up as the greatest film ever made by many. Whether people today still share that sentiment is unclear, but Criterion has certainly help it to maintain exposure. Because of Grand Illusion and The Rules of the Game, Renoir is often referred to as the father of French Cinema, helping to give it notoriety throughout the world. Renoir was indeed a bit of a Renaissance man in cinema, as he wrote, directed, and produced all of his own movies, and even acted in a few as well. He was also not afraid to inject his own points of view into his movies, as many of them are often social critiques. The Rules of the Game in particular became something of a scandal in it’s time with it’s frank social commentary attacking the upper social class. Eventually, his politics led to his exile from France due to the occupation of Nazi forces within the country, who made his films strictly “verboten” to the public. Renoir eventually settled in Hollywood where he would make a string of artistic but still compromised films. Still, he held a special place in his heart for his early French films and their journey towards cinematic redemption in the years after World War II are a fascinating story in themselves. The Criterion edition of The Rules of the Game in particular does a great job in helping to shed a light on a film that in retrospect stands as an important cultural marker for both French and world cinema.

The Rules of the Game as a title refers to the societal rules that both of the classes must adhere to within a strictly stratified society. The story centers on a collection of French aristocrats and the servants who wait upon over the course of a night within a palatial countryside chateau. Over the course of the night, tangled relationships begin to start boiling to the top and threaten to break apart the fragile facade of the “game” that all of them are playing a part in to maintain appearances. The primary thrust of the story comes from the love triangle between Andre Juieux (Roland Toutain), a beloved celebrity pilot: Christine de la Cheyniest (Nora Gregor), the woman he’s been having an affair with; and the Marquis Robert de la Cheyniest (Marcel Dalio), Christine’s husband, who also has his own side affair going on with a mistress named Genevieve (Mila Parely). With the help of Andre’s friend Octave (Renoir himself), an acquaintance of the Marquis, Andre is able to gain an invite to a lavish ball being held at the Marquis’ chateau, with the intent of getting close to Christine in order to share his true feelings for her. Meanwhile, Christine’s maid Lisette (Paulette Dubost) is being pursued by a newly hired servant named Marceau (Julien Carette), whom she has a playful little flirtation with, which draws the ire of Lisette’s husband, Schumacher (Gaston Modot), the estate’s groundskeeper. As the night’s festivities go on, the various love triangles begin to cross paths, and mayhem ensues. The Marquis’ scandalous marriage turmoil begins to undermine his rich aristocratic veneer, while the staff’s inability to keep their professionalism on course throughout the night with jealousy running rampant threatens to strip away any amount of dignity they might have had in the eyes of the ones they served. And thus, the rules end up getting consistently broken by people desperate to keep the game going, despite not seeing the apparent truth right in front of them; that they are all flawed human beings with the same desires and bad judgments regardless of their position in life. And in the end, misunderstandings and unchecked jealousy inevitably leads down to the road of bloodshed.

Perhaps even more fascinating than the movie itself is it’s road to redemption in the years since it’s release. Even though the movie has gone on to influence so many other films and shows, it may surprise you to know that it was a financial disaster when it first premiered. At the time, it was the most expensive movie ever made in France, costing around 5,000,000 francs, which would be north of $100,000,000 in today’s money. This was largely due to the lavish interior sets that Renoir had constructed, some of which were so spacious that you could only capture the full breadth of them in wide shots. Renoir needed a strong showing not just at the French box office but also in the international market to break even, and considering the incendiary nature of the film’s overall message, that was going to be a steep uphill climb. The film was almost immediately suppressed by influential people in the French upper class, who objected to being portrayed in such a foolish light in the film. Renoir would continue to tinker with the film in order to attract more of an audience, cutting nearly a third of the film down over time. And then, the war reached the French borders, and Renoir and his many collaborators had to suddenly flee in order to escape Nazi persecution. Like I mentioned before, many resettled in Hollywood and even had prosperous careers there. You may even recognize actor Marcel Dalio who played the Marquis, because he turned up in Casablanca (1943) as the croupier at Rick’s Cafe. Sadly, Renoir had to leave his original films behind, and as the war went on, many of the original camera negatives to his movies were destroyed, including the original cut of Rules of the Game. After the end of the war, Renoir sought out whatever he could to reconstruct his nearly lost masterpiece. Thankfully, copies had been held in vaults across Europe and, in time, he managed to assemble a nearly full reconstruction of the film. To this date, only one scene remains missing, but Renoir was satisfied with what he had and deemed the missing scene inconsequential. The film enjoyed a celebrated re-release in the 1960’s and since then has become the beloved cinematic classic that it remains to this day.

There are a lot of factors that have helped to keep Rules of the Game a relevant film throughout the years, and I think primary among them is the humanity that Renoir puts into the characters. No matter what the person’s social standing was, he treated each person’s story with the same amount of importance. This was unique at the time, as domestics often were relegated to the background of the story, merely there to be window dressing as the movies spotlighted the glamorous lifestyles of their principle characters. But here, the characters downstairs are fully fleshed out people as well, with intriguing dramas of their own, which sometimes even mingles in with the upper class itself. Renoir was interested in the human condition, and found the environment of a palatial countryside estate to be a perfect setting to explore the follies of separating the classes. It should be noted that Renoir’s film is a critique of the people and not a condemnation. None of his characters are truly bad, but the system they prop up is indeed the thing that he intends to scorn. One of the film’s most famous scenes is the Rabbit Hunt halfway through the movie, which is also it’s most controversial. The movie shows real animals (rabbits, pheasants, ducks) being gunned down by the hunting party in a shockingly frank depiction. The scene is a not so subtle metaphor to the horrors of war, which Renoir himself experienced during World War I, with the animals being stand ins for soldiers dying in the field. In this scene, Renoir is pointing the finger at the upper classes of Europe who seem to treated war itself as a bit of sport without ever taking into consideration the consequences it leaves behind on both the lower classes and the country itself. In many ways, he used this metaphor as a stark warning to the people of France to become more aware of dangerous recklessness of their game of social manners, as it brings danger even closer to their door, which no doubt was on Renoir’s mind as Fascism and Communism were on the rise in Europe. The movie’s ability to make compelling human drama across the entire social spectrum, both rich and poor, made the film more fascinating in the years beyond it’s release and has been the thing that has remained influential to other films today.

Criterion has given the movie another stellar restoration in order to preserve it for future generations. As stated before, the original camera negative was a casualty of World War II, and for a time, people were worried that it would remain a lost film, much like Orson Welles’ severely compromised Magnificent Ambersons (1942). The restoration of the film was a painstaking effort and the condition of each film stock was mixed. Eventually, enough work was done in order to make it feel like a whole piece once again. Criterion has gone even further, taking the 1960 restoration as their blueprint and conducting even further clean-up using the digital tools of today. With enhanced color timing and a thorough washing off of all scratches and warps made to the film over 80 years, Criterion now has a new pristine digital master that helps to bring the movie as close to it’s original look as it possibly can. Because the original negative is lost forever, we can never have an exact duplication of the film’s original clarity, so the picture can be a little soft at times, but the blu-ray transfer does it’s best to retain the fine detail within each frame. The contrast in the blacks, whites and grays all look incredible, and help to showcase the lavish sets that Renoir had constructed for the film better than we’ve seen in years. The movie’s soundtrack has also been given a polish to help it sound up to date. The famous hunting scene in particular sounds very good, with each gunshot carrying the intended jarring effect. For a movie this old, and one that has had a troubled history up to now, this is a stellar restoration that is likely to be the best we can ever expect. And given Renoir’s artistic background, holding visuals up to a high standard, he would’ve probably approved of this restoration himself.

The supplemental features are up to the usual high standard that you’d expect of the Criterion Collection. First of note is a film introduction by Renoir himself, which he filmed specifically to show in front of the movie before it’s 1960 re-release. He explains why it’s such an important film to him, especially with regards to the themes. He also shares a fascinating anecdote about how one angry viewer even tried to burn the theater down that the movie was screening in. There are a couple excerpts from two television documentaries about Renoir, one from French television and another from the BBC. They both specifically center on the period in which he was making Rules of the Game, helping to shed context of the movie’s place within his overall career. A video essay also spotlights the film’s initial, problematic release, as well as the year’s long restoration that helped to resurrect it for a new generation. A vintage interview with the film’s restoration team on a French television series called Les ecrans de la ville also gives more background to the reconstruction of the film. Renoir historian Chris Faulkner also recorded scene-specific analyses just for Criterion, where he discusses more about the film’s underlying themes, it’s controversies, it’s history, and even a bit more about Renoir himself. There’s also a commentary track written by film scholar Alexander Sesonske and read on the track by filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich. A comparison of the film’s two alternative endings is also featured, as are interviews both new and archive from people like film critic Olivier Curchod, set designer Max Douy, Renoir’s son Alain, and actress Mila Parely. As usual, Criterion treats all their titles to a wealthy collection of bonus features that are there to please the film buff in all of us and give us the most in depth look into these beloved classics.

It’s hard to watch The Rules of the Game now and not see it’s DNA found in every period drama today that portrays the day to day lives of the fabulously wealthy, and the hard working people behind the scenes there to help keep up appearances. It’s even more surprising that the genre continues to remain strong even today, with a surprising juggernaut like Downton Abbey continuing to remain popular, even as it makes it’s way to the big screen. But the remarkable thing is that The Rules of the Game feels even more relevant now than ever. As the world has again spiraled into political unrest, a story like Rules of the Game once again feels like a dire warning. Social inequality doesn’t present an ideal society, despite the allure of decadence. Trying to maintain your place within the “game” eventually blinds you to what’s going on, and eventually the struggles of the lower classes boil up and will eventually break the game apart in total. For Europe in the 1930’s, it was the rise of Fascism, which the French elite paid no mind towards, until the Third Reich were marching their way down the Champs Elysee. Today, we are seeing inequality become a factor again, and it in turn is leading to a rise in populist sentiments, which is disrupting political order and is literally splitting nations apart, all the while our entertainment seems to remain distracted by celebrity culture. Renoir wanted to spotlight the human condition within a decadent world, and pull back the facade to show how little difference there was between the classes, and how corrupt the system was in trying to maintain that lie. Shows like Downton Abbey and Upstairs/ Downstairs aren’t quite as incendiary as Rules, but they do share Renoir’s passion for treating all the characters with the same amount of importance. Because of that, we find relatable people that we can identify with in each story and imagine where our place might be in this kind of society, which helps us to contemplate where we stand in our own world. It’s legacy lives on many years later, but The Rules of the Game more than anything represents a fine cinematic representation of art and storytelling coming together in a deceptively simple yet compelling way, with Criterion’s excellent presentation and package, it will continue to inspire more like it in the years to come.