I’ve often written on this blog about the first couple phase of a film’s life, namely the creation phase of a movie and also the presentation phase. But there’s one other phase of a movie’s life that I haven’t explored as much and that the final phase; home entertainment. Sure, streaming has been discussed much lately and that falls under the umbrella of home entertainment, but what I want to talk about here is the unique culture that has arisen around the market of physical media, and how that has evolved over the years. Movie aficionados like myself have our preferred ways of consuming entertainment, and it often is reflected in the ways that we also collect movies once they are available to purchase. Home video started off as a niche market to begin with, but over time grew into one of the largest segments of film distribution within the industry. Now with the rise of streaming, the home entertainment market has changed once again and it has in many ways diminished physical media as an essential part of the life cycle of movies. But, that doesn’t mean that physical media has disappeared all together. Instead, the home video market has shifted more into a specialty mode, with physical media carrying more of a prestige than it once did, and as a result, a higher value as well. But what makes physical media stand out when compared to what someone might find on Netflix or Amazon for instance? What makes buying a movie take on more of a value than either renting or streaming it? In many cases, it not the movie itself that matters, but the way that it is packaged and presented that gives it more value in the physical media market. Movie collections often become just as beloved a part of someone’s personal belongings than anything else. In many ways, it’s something that connects us closer to the movies than any other form of media consumption that is offered up by Hollywood.

For me personally, my journey as a film buff has been largely tied to the way that I collect movies. It goes all the way back to my childhood even. Instead of asking for video games or sports equipment as gifts from my parents like my siblings would on birthdays and Christmas, I always wanted movies on video tape to add to my growing collection. I grew up in the 80’s, when VHS cassettes were coming into their own as the primary form of physical media for home entertainment. And the company that took advantage the most out of this growing market in the 1980’s was Walt Disney Pictures, which naturally I was the target audience for. I remember receiving Lady and the Tramp (1955) as my first movie on video tape when I was 5 years old, and it left an immediate impact on me. In the years after, Disney began releasing their back catalog of titles, and even began using their new Home Video label to bring their brand new classic films, like The Little Mermaid (1989), to a home audience. As I collected more movies, I began to self teach myself about the history of the Disney company, and how every movie had a canonical place within the timeline of the studio. This was largely due to the fact that every box labeled the movies in the chronological order that they fit within the Disney canon. By the time I had reached high school, I had every Disney movie on VHS cassette, from Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937) all the way up to Hercules (1997), which marked 35 movies in total. But, what started as a childhood collection for me extended beyond just wanting to have each one of those movies as a part of my collection. In retrospect, I see those movies as the key to helping me deep dive into the history of film itself, through the lens of one studio. By knowing everything there is to know about the body of work of a single studio, it allowed me to see the incredible mark that cinema leaves in general, and it sparked my interest to explore beyond just what Disney ended up making and look at the history of film as a whole.

Apart from the entertainment value that I would get from the movies I owned, I also have realized over the years how much the aesthetic of physical media matters as well. In many cases, a well packaged movie plays just as important a role in selling a movie as anything else. One of the things that I liked best about the Disney movie collection on VHS was the way that they were packaged. For the most part throughout the history of VHS cassettes, the majority of movies that were released by the major studios packaged their films in flimsy, cardboard sleeves with artwork printed on the front, back and spines. Disney, however, opted to package their films inside insulated, plastic clam shells, which to a young collector like me made them feel a little bit more special than the other movies for sale. And when I had them all on my shelf at home, they often looked to me like books in a library, with each title specially designed to stand out. Aesthetics mean a lot to collectors no matter what the item may be, and the best producers of home video packages were well aware of how each of their title would look in the consumer’s home. By the end of the VHS era, box sets had become a niche market that had come into it’s own, with movie fans willing to pay the extra little bit to have a movie on their shelf that not only was important to them, but could even stand out as a work of art on it’s own. One other thing that I always found interesting in that era, which in turn also helped me to expand my interest in film, was the aura of the double cassette boxes. These were usually made for movies that were so long, that they had to be split up into two cassettes, which to me made them feel even more special. In that time, it was movies like The Ten Commmandments (1956), Ben-Hur (1959), Dances With Wolves (1990), Braveheart (1995) and Titanic (1997) that were given this treatment, and the fascination that I had with movies that were too big for one tape became a big part of what pushed me into exploring beyond just what I knew about films from Disney. If movies weren’t packaged the way they were like they had been in the VHS era, I wonder if I would’ve still gone down the road of film fandom that I ultimately did.

Things did change in the turn of the millennium, when VHS gave way to a new form of home entertainment; DVD. Instead of cassette film, DVD’s encoded movies onto compact discs, thereby opening the world of cinema up to the digital age. The same technology had been used for years prior on the laser discs, but DVDs were more economical to make and own and fit much easier on a bookshelf. The picture quality also put VHS to shame, which of course led to a significant downturn for VHS production. But what may have been the most significant contribution of the DVD era was the implementation of bonus features as part of the package. Another carryover of the laser disc format, bonus features reached a new level of popularity with the rise of DVD. Ranging from making of material to alternate audio tracks and even alternate cuts of the movie, DVD bonus features really raised the overall value of the movie that a person was purchasing. And often the success level of a movie on DVD could be determined by the amount of bonus features that it offered as a part of the set. This also led to the first instances of people buying a movie in a new format that they already owned in another. I certainly am guilty of that many times over now. I have probably purchased the movie The Lion King (1994) five times now across four different formats; VHS, DVD, Blu-ray (twice), and now 4K. And why is that? For me, whenever a new special edition of a movie is released on home video, I weigh my choice of purchasing on whether it offers anything more that the other editions did not have. A lot of films don’t do this, and usually I’ll find that I make one lifetime purchase with said films when they become available. But there are certain offers on new re-issues that I can’t pass up and I’ll pay that money again, even though I have owned the movie before. Disney, the clever marketers that they are, have their so-called “Disney Vault” release plan, where their movies stay in circulation for a short time, then go back into the “vault” and out of distribution, thereby driving more demand for the film, which they’ll then re-release again in a big new, specialty package. Sure it’s market manipulation, but it works, and it’s gotten me every time.

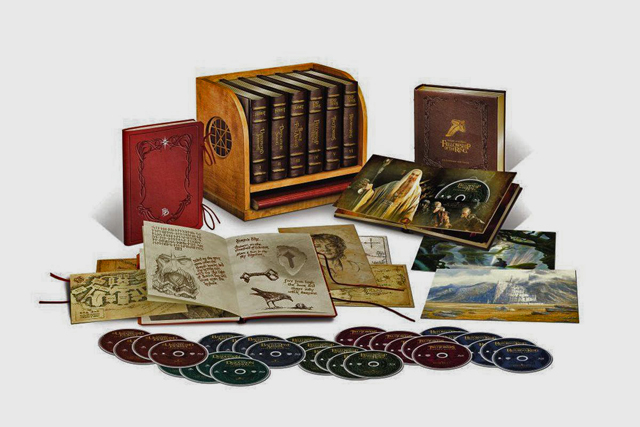

But there is one thing that I as a consumer really found myself valuing with the introduction of bonus features on the DVD format, and that was the in depth making of material that were found on certain special editions. Not only did they spark my interest as a film history buff, but they even inspired me to want to work in the world of filmmaking itself. Perhaps no other film release on the DVD format left a bigger impact on me as an aspiring filmmaker than the Extended Editions of the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Filmmaker Peter Jackson did the extraordinary thing of having cameras roll behind the scenes the entire time while he was putting together his epic film trilogy. He invited behind the scenes documentarian Michael Pellerin to document every level of production, from the script phase to the final picture lock, and the whole complete wealth of material ends up eclipsing the movies themselves in length. In keeping with the Tolkein theme, the collection of documentaries that Pellerin and his team compiled together are known as the Appendices on the special edition, and many film collectors will tell you that the entire package feels like having a film school master class in a box. Peter Jackson would continue to pull back the curtain and reveal all the tricks of the trade in his follow up movies King Kong (2005) and The Hobbit trilogy in what he described as Production Diaries, and it could be said that an entire generation of filmmakers were inspired solely because of the documentaries on these DVD sets. Even aesthetically they were pleasing to the eye, emulating volumes of books much like the ones the movies were based on. Peter Jackson and Michael Pellerin certainly didn’t invent the DVD bonus feature, but they raised the bar high for the decade that followed, and as a result, the DVD era saw a flourishing of in depth making of material as a necessary element in home entertainment.

But, for many home video collectors, quality can sometimes be valued over quantity when it comes to all the bells and whistles. One label in particular has made it their mission statement to deliver movies as a prestige product above everything else, and it’s one that I’ve talked about so much on this site that I devote an entire series to them; the Criterion Collection. Criterion not only puts a great amount of work into presenting the movie itself in the highest possible quality, but it makes the package you buy it in just as much of a prize in itself. The Criterion Collection caters to the film collector specifically, with the aesthetic of the box art given it’s own special consideration, knowing full well that the person who is buying a title in their collection likely owns a few more of their titles as well, so they’ve got to make it feel worthy of the label. Each Criterion title maintains that aesthetic integrity from the box art all the way to the disc menu, and that’s part of the appeal of the Collection to most film aficionados. There is a prestige to their presentation that you don’t find from most other publishers. This includes a booklet found beside the discs that includes scholarly essays that gives the consumer a richer view of the movie that they have just purchased. The bonus features from Criterion, many of them made in house, also illustrate the “quality over quantity” idea behind prestige entertainment. Special Editions straight from the studio often package as many EPK materials as they can onto the disc and believe that it fulfills the criteria of a “special edition.” But Criterion opts to in depth analysis into a film’s making and it’s themes on a larger sense. Often, the total number of features may be less than the studio label, but the quality will be much more enriching. When a movie receives the Criterion treatment, it’s seen as a badge of honor, and that is what has helped to make Criterion a valuable brand in the home distribution market. And that special level of prestige is likewise what makes it less embarrassing for film nerds like me having to rebuy a movie that we already own.

But, like a lot of other aspects about the film industry, home video collecting is changing in the wake of the rise of streaming. Indeed, home video sales have plummeted over the last decade since the heydays in the 2000’s. And that’s in large part due to streaming taking over so much of what was the backbone of the home entertainment business. Home video rental houses, like Blockbuster, are pretty much extinct now, and movies are readily accessible to buy, rent, and stream digitally from the comfort of home. In the aftermath of the end of the rental market, and the declining sales of disc based media, we are starting to see how little of a market movie collecting really is. When people were buying up movies by the dozens from their local video store, it was because there was no other option available for movie ownership. Now that streaming has made it easier to access movies from the safety of home, more and more people are drifting to the option that is far more convenient and adds less clutter to their book shelves. What’s left are the die hard movie collectors that want to have that physical movie to hold in their hands, and it’s a market that is likely going to grow smaller in the years to come. As a result, the physical media market is changing to appeal to the niche market once again. Movie studios are keeping their inventories lower on new releases due to the smaller demand, and in the process, the movies themselves are becoming a more elusive commodity. Labels like Criterion are still thriving, because they’ve always operated this way, but the major studio labels are having to rethink what they should invest in when it comes to physical media. Extra special editions, like those that include not just the movies , but special collectibles as well are becoming more prevalent, but also at the same time, more rare and expensive. The Lord of the Rings trilogy even put out an $800 special edition set that included the Hobbit movies, all packaged in special leather bound boxes and stacked on a special, hand carved wooden shelf. It’s a high price for a movie set that most people already have, but for what it is offering, it becomes less about the movies themselves and more about the exclusiveness of the package itself. It may seem outlandish, but it could also mean the future of physical media in the long run.

It’s hard to know at this moment what physical media in home entertainment will look like a decade from now, but there is no doubt that the market is changing. We may not see the likes of the incredible Lord of the Rings Extended Editions box sets again, but I also believe that very few people are ever going to through their original copies away either. There’s just something to be said about a complete, aesthetically pleasing special edition package of a beloved movie that holds a special place in the hearts of film lovers. It may be the end of a movie’s life cycle, but it’s also the phase that connects a movie to it’s fan more than any other. When you hold the movie in your hands, it means a whole lot more to you; it’s yours to watch forever. The Criterion Collection understands this, and they cater to what their audience wants by making each film feel special. They have even remarkably convinced streamers of this as well, as Criterion has become the physical media home for films from Netflix, like Roma (2018), Marriage Story (2019) and The Irishman (2019). If Netflix can be convinced to put their high profile, exclusive movies on physical media, then there is still hope. I for one am an undeterred film collector, still buying some of the same movies over and over again. I’m particularly a completionist with Disney movies, having own each canonical film on VHS, DVD, and Blu-ray, with 4K well on the way next. And yes, they are all organized in chronological order, just like I did with my VHS tapes back when I was a child, because that’s who I am. Even still, if a movie catches my eye in the sadly shrinking video sections at Target and Best Buy, I will make it a part of my collection that is now numbering in the hundreds. I consume digital media as well without complaint, but a part of me will always desire a hard copy above all else. It may be long past it’s glory days of filled to the brim special editions, but physical media has found a devoted fanbase that continues to support it, and it’s one that I hope continues to hold these movies up to a high standard, with quality standing above all else.