It’s hard to contemplate how harsh the Great Depression was on working class Americans so many years and generations after it happened. Today, we worry about pandemic related mass unemployment and supply chain disruptions resulting from a year of lockdowns, but the Great Depression was a whole different kind of monster. With an unemployment rate that reached a staggering 24% of the population which persisted for several years due to stagnant growth in the economy, it still remains unchallenged as the greatest economic downturn in US history. With the stock market crash came the collapsing of the banks, which could no longer provide loans to boost business or help average citizens hold onto their homes. Eventually, foreclosures drove many people out of their homes and into tenement camps that later became known as “Hoovervilles,” named after then President Herbert Hoover, whose botched handling of the economic crises was largely blamed for the prolonged Depression. It was a harsh time in America, as people were desperate to find any work they could, and that often led to many people falling victim to scam artists and greedy opportunists who would prey upon the desperate for cheap labor. This in turn led to a rise of push back from the workers, and they started organizing and demanding better may and living conditions. Sadly, the workers faced resistance by being labeled communist agitators, and wealthy business owners used their powerful influence to manipulate the legal system to deny workers the rights that they were seeking. Still, the rise of unionization and the clear devastation brought on by the poor handling of the economy led to a change in the American political system, which eventually led to the election of Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt to the presidency, who ran on a promise of a “New Deal” overhaul of the Social Welfare system in America. Though it would take many years of tough battles in the halls of congress, Roosevelt eventually got his New Deal programs passed, which brought about pivotal new safety net measures, like Social Security and a Federal Minimum Wage. Probably no other era in 20th century had as much of a profound effect on the future of America as those Depression years.

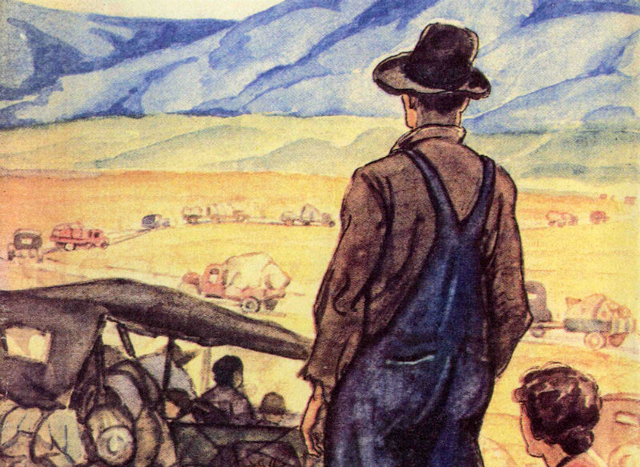

And yet, as time has pressed forward, the lessons taken from the Depression seem to have faded as well. Today, we take Social Security for granted, and unionization is at the lowest level it has ever been, which in turn has led to another era of wealth inequality and corporate exploitation of labor. What we have left to remind us of the horrible legacy of the Great Depression are the stories told by our elders and the documentation of that time period that survives to this day. The Dorthea Lange photographs of migrant workers living in Hoovervilles still vividly capture the horrific reality that ordinary American citizens endured over those years. Several news articles and news reels that have survived also have given us an idea of what it was like, though they feel more and more detached so many years later. For many, the most enduring portrait of the horrors of the Great Depression comes from the pages of what many consider to be among the “Great American Novels;” John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, as well as the famous 1940 movie that it inspired. Born and raised in Salinas, California, Steinbeck saw the effects of the Great Depression all too clearly, as he witnessed the mass migration of poor farmers from the Prairie states making their way to the fertile lands of his home state, only to see them being either threatened, mistreated or generally exploited by his fellow Californians once they got there. In his writing, he expressed sympathy for the working man, and sought to tell their story. He wrote articles for the San Francisco News about the plights of the migrant workers in a series that came to be known as The Harvest Gypsies, which told the story in the workers’ own words. He would also write many short stories and novels that offered many different windows into the lives of poor working farmers, such as Of Mice and Men and of course The Grapes of Wrath. His writing has often been described as Dust Bowl Fiction, relating to the simultaneous catastrophe of the Dust Bowl famine of 1935-36, which exacerbated the Depression even further. Though a lot of his writing gave a much needed compassionate voice to the too often overlooked migrant worker, it was not always met with favorable reception.

“Takes no nerve to do something, ain’t nothin’ else you can do.”

John Steinbeck wore his New Deal progressive politics proudly on his sleeves, which often opened him up to accusations of being a communist sympathizer or just an outright card carrying member. The Grapes of Wrath was his most pivotal work to date, detailing through the eyes of one family all of the harsh realities of Depression Era exploitation. In his novel, he makes no illusions of where he stands, with every authority figure and capitalist portrayed as corrupt, and the only compassionate party in the story other than the migrants are the supervisors of a Government run camp that helps keep the law enforcement at bay. For it’s perceived anti-capitalist viewpoint, The Grapes of Wrath was banned in many corners of the country, with censors fearing it would inspire communist infiltration of the workforce. Even in Steinbeck’s home state his novel met resistance, with the Kern County Board of Supervisors out right banning the sale of the book. But one other part of the state that responded well to Steinbeck’s novel was Hollywood, and in particular, a very unlikely champion named Daryl F. Zanuck. Zanuck, the head of 20th Century Fox, was a lifelong Republican, but he was sympathetic to the struggles of the working class during the Great Depression and the movies from his studio often reflected a progressive attitude towards social issues. Naturally, he found the appeal in Steinbeck’s vivid portrait of Depression era suffering. and optioned the novel right away, long before it even went into wide publication. Still, Zanuck had to get around the censorship issues that plagued The Grapes of Wrath. He sent investigators to tenement camps up and down the state of California to see how accurate Steinbeck’s accounts of the horrific conditions the migrant workers lived in were. Not only did their findings back up Steinbeck’s accounts, but they proved to be even worse than expected. With that knowledge, Zanuck knew that it was not only worthwhile to adapt The Grapes of Wrath for the big screen, but also essential. He tapped one of the most celebrated filmmakers of that period, John Ford, to bring the novel to life, and it would prove to be one of the most ideal matches of filmmaker and author Hollywood would ever see.

“I never had my house pushed over before. Never had my family stuck out on the road. Never had to lose everything I had in my life.”

John Ford’s film largely sticks pretty close to the book for the first part, but diverts significantly in the later half. Those second half differences in particular reveal a lot about what it took to get the movie made in the midst of the threat of censorship. It also reveals a lot about the different world views of the author and the director. Even with the limitations, the movie still manages to paint a vivid portrait of the Great Depression and the horrifying affect it had on the people who lived through it. Like the book, we are introduced to the Joad Family, a tightly knit unit of Oklahoma farmers, known as Okies, who have no other choice than to hit the road and head off to a hopefully better life in California. After the bank forecloses their farm, with the Dust Bowl rendering their soil useless, the Joad family straps everything in their possession to the back of a beat up old truck and leaves the land that has sustained them for generations behind. The book and movie detail the sights and events that follow them along the way as they drive down Route 66 to their destination. The movie removes a couple of the different vignettes on the road trip out, but still keeps the important ones in the film, including the losses of loved ones. Where John Ford really proves he’s the perfect director to tackle this kind of subject matter is in his no nonsense approach to his visual story-telling. His film feels completely devoid of the usual Hollywood glitz and you would almost believe that he’s shooting a documentary at times. One of the most remarkable moments in the movie is when the Joad Family arrives at their first Hooverville in California, and Ford shows their arrival through an incredible POV shot from the front of their truck. The camera pans across the view they see of the camp, with poor and destitute people staring back as the truck passes through. You really see the influence of Dorthea Lange’s heartbreaking photographs in this memorable POV shot, with the camp appearing to be the real deal. This must have been a shocking thing for audiences in 1940, which was only a couple short years removed from the worst years of the depression. People who avoided seeing the conditions within these camps were now suddenly witnessing it first-hand on the big screen, and the Ford style was very instrumental in making that happen.

But what mattered the most in making the story resonate within the film was how well audiences connected with the characters. In many ways, this is where we see some of the big differences between the novel and the film. In Steinbeck’s novel, all the members of the Joad family are spotlighted with their own different struggles during the journey. In the film, it’s really only three principle characters that are focused on. One of course is the protagonist eldest son of the family, Tom Joad. Tom Joad was very much a coveted part to play, as he embodied the idealized American working man identity, fighting for justice in a world that has treated the helpless poorly. Daryl Zanuck would end up giving the role to one of the rising stars in Fox’s stable of talent; a young man named Henry Fonda. Fonda had already been under contract at Fox for many years, but had never been the central lead in a film until now. With Tom Joad, Fonda’s folksy Nebraska background came in handy, because he could believably portray a destitute migrant farmer while still maintaining his movie star, golden boy profile. In many ways, straddling both of those two worlds enabled Fonda to create Tom Joad into this more mythic figure as a result; becoming the epitome of the righteous crusader for the rights of workers. Something I’m sure Fonda welcomed as he shared much of Steinbeck’s progressive political views. Apart from Tom Joad, the other crucial characterization that’s central to the story is that of Ma Joad. Ma’s part in the story is more or less exactly as Steinbeck wrote, with her being the crucial glue that keeps the family together through all the hardship. But, as the movie elevates Tom Joad to a more central role in relation to everything else, her maternal relationship to him likewise also gets elevated. Veteran actress Jane Darwell, in the role that won her a supporting actress Oscar, is absolute perfection as Ma Joad. Her resilience and practical outlook on life is both inspiring as well as heartbreaking. She has got to be the pillar of strength that keeps hopes up even as the seems to be none left. And Ms. Darwell perfectly conveys that in her performance. A particularly memorable scene comes early as she burns the last of her remaining possessions before they leave their Oklahoma homestead. When she looks at herself in the mirror while dangling a pair of old earings next to her head, she conveys without words the warming nostalgic memories of her past and how the dread of the future cast a cloud on her now. They are both two mighty performances that bring these pivotal characters to life.

“Tom, you gotta learn like I’m learnin’. I don’t know if right yet myself. That’s why I can’t ever be a preacher again. Preachers gotta know. I don’t know. I gotta ask.”

The remaining members of the Joad family are all still present, but Ford’s film chooses to relegate them to very minor roles in comparison to Tom and Ma. Instead, the other character given focus in the story is an unrelated tag along on the Joad’s journey named Jim Casy. Casy is a one time preacher who lost his faith and believes like the Joad family that a better life may await him in California. He’s pretty much exactly the same kind of character as he is in the books, played memorably in the movie by Western film stalwart John Carradine. Casy, in many ways, is where Steinbeck brings in his own voice to the story, as the character begins to become the voice of righteous indignation to the mistreatment of the migrant farmers. Though he’s a man who lost his faith before the beginning of the story, he becomes enlightened again after seeing the injustice committed all around him. He radicalizes and begins to assemble other workers to join him in unionizing. It’s largely because of the character of Jim Casy that the book found so much resistance from the censors. One, the character was a sympathetic and in many ways inspirational view of a labor organizer, someone that the capitalist establishment was desperate to vilify. Secondly, it’s pretty clear that Steinbeck also wrote the character as something of a Christ allegory, one of many allusions to religious symbolism in the book as a whole. His initials are JC after all. And in the same spirit as the symbol he represents, Casy also meets his end not long after his enlightenment, leading Tom to pick up his mantle after being shaken by Jim’s murder. For a lot of establishment figures, the use of this Christian allegory was especially seditious in their eyes, particularly those in the Religious Right. That, as well as a lot of the frank depictions of violence and sexuality in Steinbeck’s novel led to to it being so widely banned across the country. For Zanuck and Ford, they needed to find a way to make the message of Steinbeck’s writing work without running into those same censorship hurdles. Carradine’s performance greatly helps to make Jim Casy a believable character. He’s not overtly Christ-like in the way the character in the book is, but he still comes across as an inspiring voice that brings to the front all the righteous rage his character should have. Carradine’s mellow voice and wide hopeful eyes also help to imbue the character with the same kind of spirit that Steinbeck’s words bring to the character. To make this character work and appeal to a broad audience, the filmmakers managed to walk that fine line perfectly.

Essentially, the movie tempers the more radical nature of Steinbeck’s prose while still retaining it’s essential spirit. But where Steinbeck and Ford diverge is in their ultimate outlook on the fate of the Joad family, which in many ways reveals how both men viewed humanity as a whole. The endings of the books and the movie are very different, which in some ways make sense considering what a book can get away with more than movie. Both stories do eventually lead to Tom Joad’s departure from the family, as he is being pursued by the law for killing the man who slayed Jim Casy. But what happens after that is where the split happens. John Ford follows up Tom’s heartbreaking exit with a beacon of hope for the Joad family. A good job opportunity has presented itself, and the Joads hit the road for Northern California with hope that something good waits on the other side. In these final moments, Ma Joad reflects on how, after everything that has happened, the family has the ability to press on and be hopeful. In her words, “we’re the people,” she basically underscores the idea that by sticking together, they’ve managed to make themselves stronger, and that is what will get them to an eventual better life. It’s basically a statement to reinforce the idea of change through solidarity, reinforcing the call for unionizing that the book promote. Steinbeck on the other hand leaves the story on a bit more bleak note. Things don’t go well for the Joad family up to the final page. The eldest daughter of the family, Rose of Sharon, has been with child for the entirety of the story. In the final chapters, she gives birth to a stillborn baby. After this tragedy, the Joad family are also forced to take shelter from a storm during their travels. When they find an abandoned barn to hide in, they also find another migrant farmer dying of starvation. Realizing the man’s need for nourishment, both Ma Joad and Rose realize what they must do. So, in a rather bleak final note to end the book on, Rose let’s the starving man drink the breast milk that she’s been lactating post-pregnancy. You can probably see why John Ford opted for his ending. It does offer an interesting contrast, though, as Steinbeck seems to express a more pessimistic outlook on the state of humanity. Ford clearly wanted to inspire his audience with a glimmer of hope, but Steinbeck clearly wanted us to see just how bad it had gotten in America, and that hope was very much fleeting. Steinbeck’s ending overall feels far more like an indictment of the system that he viewed as broken. I imagine this must have been an image that he probably witnessed while investigating the camps, and it’s one that he wanted the reader to clearly understand as well. Both Ford and Steinbeck clearly wanted to instill sympathy for their subjects, but Steinbeck’s approach feels far less like a Hollywood ending, and more of a wake-up call to his readers to see the world for how it really is.

“Wherever there’s a fight, so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready, and when the people are eatin’ the stuff they raise and livin’ in the houses they build – I’ll be there too.”

With nearly a century gone by since the deepest depths of the Depression, we have less of a comprehension of how bad it got. My one connection to that time comes from the lessons I learned from my Grandparents. My Grandpa and Grandma on my mothers side in particular were very familiar with the kinds of narratives found in John Steinbeck’s novels, because they themselves grew up in the same California farming communities that these migrant farmers flocked to during the Depression. They didn’t tell me much about the horrific kinds of exploitation that was going on during that time, partially because they weren’t near any of those farms and they were probably too young to realize what was going on. They did tell me about how their families often had to ration goods in those days, and that something as commonplace today as an orange was seen as a luxury to them during the Depression. As a tradition every Christmas in the years since, my grandparents would place an Orange in our stockings, done as a way to remind all of us of what their families went through to endure the hardship of the Depression. It’s certainly the thing that introduced me to the reality of the Great Depression. Though my grandparents were as heavily effected, they nevertheless remembered how hard it was, and they didn’t want us to forget too. That’s why John Steinbeck’s Pulitzer winning The Grapes of Wrath is not only an important story to remember, but an essential one as well. It shows the depths that humanity can fall to when pushed to it’s limits, and that all that we have left after we’ve lost everything else is our own compassion to each other and the willingness to do good in spite of such bad odds. John Ford managed to bring the essence of Steinbeck’s to the big screen, albeit to the extent he could given the censorship limitations at the time. With his down to earth sense of humanity, remarkably naturalistic photography courtesy of the legendary cinematographer Gregg Toland (who also won an Oscar), and incredible lived in performances from his cast, Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath is every much just as masterful as the book that inspired it. Today, both the book and the movie’s messages feel more relevant than ever as we are seeing yet another reckoning between capital and labor erupt in America, and the same old Red Scare tactics being revived to push back against it. It’s a time like this that a movie like The Grapes of Wrath becomes essential viewing, to remind us that this kind of story happened in America, and not that long ago, and it could very well happen again if we are not careful. The pandemic certainly made that a possibility. The Grapes of Wrath, both as a work of literature and a cinematic masterpiece, are undisputedly among the great American fables, and whether their outlooks are hopeful or pessimistic, it is crucial that all of us pay attention to it for our own good as a nation.

“Rich fellas come up an’ they die, an’ their kids ain’t no good an’ they die out. But we keep a’comin’. We’re the people that live. They can’t wipe us out; they can’t lick us. We’ll go on forever, Pa, ’cause we’re the people.”