I’ve made no illusions to the fact that I am not a fan of Roland Emmerich’s work as a director. Is everything he has made been terrible? No, but the vast majority of the films he’s made have been some of the worst things I have ever seen on the big screen, and his track record as of late has been especially rough to witness. What is especially frustrating is the fact that he’s a filmmaker that has shown no growth as an artist over the course of his career. Some directors like to re-invent themselves as they enter their later years, or they try a variety of different styles and genres and then apply their own unique voice to them. Emmerich only does one thing; he makes big loud action movies with a lot of apocalyptic, environmental destruction thrown across the screen. He’s a director that has chosen to make simplistically plotted crowd pleasers that often don’t even hit that mark. But, why is he still allowed to make movies even though they are often seen in retrospect to be terrible. One could say that he knows his audience and has managed to laser focus hit that target on a regular basis. That, or he’s been coasting very much on the goodwill that he had built during his first few years in the business. Working with his creative partner, producer/writer Dean Devlin, Roland Emmerich started off as a science fiction director. Emmerich and Devlin managed to secure a modest hit with the Jean-Claude Van Damme vehicle Universal Soldier (1992) and then they won raves for their ground-breaking follow-up, Stargate (1994). But it was their third film that really put them on the map; the mega-blockbuster Independence Day (1996). If anything, Independence Day is the sole reason Emmerich really still has a career at all, because that record breaking film is the movie that propelled him to the attention of all the studios in Hollywood. But, with that meteoric rise, it’s only inevitable that something would bring a filmmaker like Roland Emmerich back down to Earth. But, what kind of disaster would be the first crack in the armor for Roland.

Following up right after the historic success of Independence Day (1996), which was the most popular film of that year by a long shot and at the time was in the top grossing movies of all time camp alongside the likes of Star Wars (1977), E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (1982) and Jurassic Park (1993), Emmerich and Devlin were seeking their next project. Instead of crafting a film off of their own fresh idea, they decided to next work on an already established IP that Hollywood was seeking to re-boot. Columbia Pictures had for many years been trying to get an American adaptation of the classic Japanese monster movie Godzilla (1954). They had been trying to coax some of the biggest directors in Hollywood, including Steven Spielberg, who was very much against the idea, stating the nothing could replace the original. Eventually, they got cinematographer turned director Jan de Bont to sign on, fresh off his success on the Keanu Reeves thriller Speed (1995). However, de Bont eventually realized that he couldn’t pull off the vision necessary for the film, and Columbia was once again left to shop the project around. The timing proved fortunate as Emmerich and Devlin were just leaving their contract with 20th Century Fox and were open to signing with a new studio. Emmerich initially wasn’t that interested in directing an adaptation of Godzilla (1998), but he later agreed to take the job after Columbia granted him creative license. With Emmerich and Devlin in place, the multi-million dollar Godzilla remake was underway. But, as the studio would soon learn, the creative license granted to a director that was initially indifferent to the prospect of directing a Godzilla feature would prove in the end to be a recipe for disaster. Unfortunately for the studio, failure on the part of the team of Emmerich and Devlin had yet to materialize and they had no insight into what was to come next.

The original Godzilla is a renowned classic the world over. Despite it’s primitive effects at the time, basically a guy in a dragon suit stepping on a bunch of model buildings, it nevertheless managed to successfully convey a sense of terror for audiences upon it’s release. The movie played upon Cold War anxieties about nuclear war and annihilation, which especially rang true in it’s native Japan, the only country in the world to this day that suffered an atomic bomb attack. The gigantic terror that is the King of Monsters, Godzilla is very much a metaphor for the uncontrollable chaos brought on by a nuclear attack. That’s why the original movie resonates so much still, because of the earnestness of it’s message, and how much the movie maintains that tone of terror. Because it was a hit both in Japan and abroad, there were demands for further tales of Godzilla on the big screen. So, Toho Productions, the creators of the character, put him in many more films in the years that followed, not just terrorizing humanity, but also fighting a whole variety of monsters, which in time became known by their Japanese moniker; kaiju. Joining Godzilla were foes like Rodan and King Ghidorah, as well as allies like Mothra and Gamera, who themselves would spin-off into their own series of films. During that time, Godzilla even evolved from a malicious terrorizer of humanity to an eventual protector of humanity. And though the movies themselves were popular in the states, despite the often awkward voice dubs and the weird shoe-horned clips of Raymond Burr, they still remained a uniquely Japanese import on American cinemas. But, with visual effects improving greatly in the 80’s and 90’s, Hollywood believed that the time was right to finally take their shot at Godzilla movie. Though Toho was reticent to the idea of a Hollywood studio using their iconic character in one of their movies, they did eventually grant Columbia Pictures the chance to make their own film version. Of course, once the film finally did get made, they probably should have trusted their initial cautious instincts from the outset.

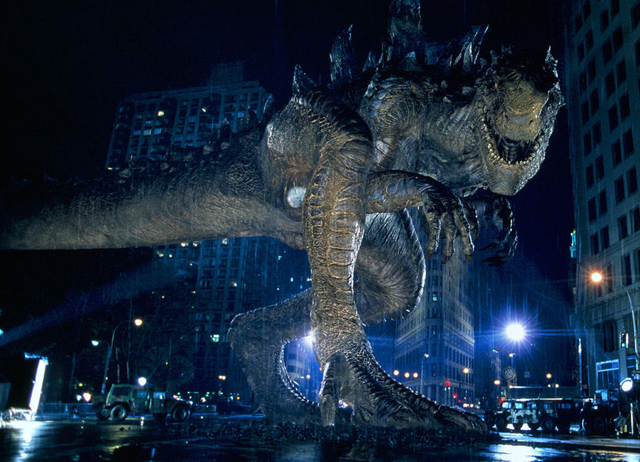

On paper, the movie has promise. Godzilla let loose in the middle of the concrete jungle that is Manhattan Island; seems right up the alley for the director that had an alien ship blow up the White House in Independence Day. But there is one thing that was key to the success of Independence Day that becomes very apparent when watching Godzilla (1998); the lack of a compelling story. Though Independence Day lacked subtlety and was full of cliches, it still had a well constructed through-line built around it’s very high concept premise that made the shortcomings feel inconsequential by the end. But, in Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla, you get very little in the way of a compelling plot. Basically Godzilla finds his way to New York, wrecks havoc for two hours, the “characters” do their best to survive and then roll credits. While Independence Day knew that you had to hang the interest of the audience on the sense of peril, the same never applies in Godzilla. Honestly, the threat of Godzilla the Monster feels small compared to the city sized space ships that destroy everything in their path. There are shots that Emmerich tries to convey the sense of scale that feels comparable to Independence Day, like seeing a Godzilla sized hole in the middle of the MetLife Building. But, that’s the unfortunate thing about how Godzilla ends up being used in this movie. The only sense of awe that we get is when we see the aftermath of what he has done. The more we actually see of the monster in the movie, the less scary he becomes. And there is a reason for that. The design of Godzilla, let’s just say, is not very good in this movie. The iconic design of the original creature, with his small snake like head on top of a bulking body with massive spikes running down his spine, is very much missed in this movie. The new Godzilla looks like an escapee from Jurassic Park. The head of the new Godzilla is unique, but you can’t tell me that the rest of his body was not stolen from a model of Tyrannosaurus Rex. In fact, the DNA of Spielberg’s blockbuster can be felt all throughout this movie, and not in a good way.

There is no doubt that part of the reason this movie was greenlit in the first place was because of the monumental success of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park. And in particular, it was the groundbreaking visual effects that spurred a revolution across the industry. Jurassic Park not only had stellar practical effects, but it also showed the world for the first time what computer animation could really do. Even 30 years later the computer animation in that film remarkably still holds up, even though it was done large with primitive software compared to what’s available today. The same cannot be said about Godzilla, even though it’s basically using the same level of effects. One big difference is how the director utilizes the visual effects. Spielberg is a master of set-ups, and he manages to move his camera around in a way that compliments the computer animation and makes it feel natural. The sweeping introduction of the brachiosaurus, the first full shot of a dinosaur that we get in the movie, is a perfect example of this. But in Godzilla, Roland Emmerich moves his camera around a lot, never really allowing us the time to soak in the visual effects. Not to mention that most of the movie is cast in nighttime darkness with an extra layer of rain, which no doubt was there to cover up the seams of the less than spectacular computer animation. Even the practical stuff looks cheap. The miniature models used for the buildings of New York City all look flat and texture-less, which really breaks the illusion. Not only that, but the marquee attraction of the film, Godzilla himself, is seen as briefly as possible in this movie. Instead, most of the film’s climax is spent with the human characters being chased by baby Godzillas, which are essentially velociraptor rip-offs. All together, it makes this movie feel smaller than it should be. It’s no wonder that when future Godzilla movies were made at other studios, they returned to that traditional bulky Godzilla look that resembles a man in a dragon suit. That, strangely enough, feels more true to the character than this oversized hybrid of a Tyrannosaurus and an iguana.

But, lackluster visual effects can be forgiven to a degree if there is a compelling story and likable characters that drive the rest of the film. Godzilla sadly did not have any of those things. The story is pretty much just a cat and mouse chase through New York, as the main characters try to coax the monster out of hiding and bring him into the open, hopefully to exterminate him. And the characters themselves are sadly the typical Roland Emmerich mix of archetypes and stereotypes. He resorts to his favorite trope once again in this movie, with the awkward nerd managing to save the day with science, which we saw previously with James Spader in Stargate and Jeff Goldblum in Independence Day. Like some sliding scale, we go from those actors to Matthew Broderick, playing yet another awkward nerd who seems to know all the right things necessary to take on a 200 ft. tall giant lizard. And if his character wasn’t portrayed weird enough, Emmerich and Devlin gave him the needlessly complicated name of Dr. Niko Tatopolous. Unique name does not equal unique personality. On top of Matthew Broderick in the lead, the rest of the movie’s cast is just, shall we say, weird. The movie features not one, or two, but three different actors who are part of the voice cast of The Simpsons: Hank Azaria, Harry Shearer, and Nancy Cartwright. Of those three, only Hank Azaria has substantial screen time, but seeing all three here does take one out of the movie. One even more distracting bit of casting in the movie are character actors Michael Lerner and Lorry Goldman playing Mayor Ebert and his aide Gene respectively, in a clear and obvious parody of film critics Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel. Why Emmerich and Devlin would throw this kind of satirical characterization into a movie about Godzilla makes absolutely no sense, and it almost feels like a petty move on the filmmaker’s part, either taking revenge on bad reviews of the past or perhaps doing it as a bit of pandering. Suffice to say the real Siskel and Ebert were not amused and they predictably gave the film two thumbs down. The one bit of casting that is borderline acceptable in the movie is Jean Reno as a military man lending his expertise in stopping the rampaging monster. The renowned French actor isn’t particularly well-used here, but out of all the actors in the movie, he’s the one that comes closest to maintaining his dignity by the end, mainly due to a suitably subtle performance. Overall, when most of your sympathy is with the giant monster, and barely even that, you know that you’ve centered your movie around some pretty bad characters.

Besides the production and story problems themselves, this movie also put a strain on the creative relationship between Dean Devlin and Roland Emmerich. This was the last screenplay that they collaborated on, and after their next film, the Revolutionary War epic The Patriot (2000), they stopped producing movies together. Though Godzilla is not explicitly the movie that caused the filmmaking duo to pursue different paths, but you can definitely see how it started forming the cracks. Roland Emmerich’s free reign on the project created more than enough headaches for the executives at Columbia. Strangely enough, the problem with this movie was not constraints made by budget cuts, but rather the opposite. The budget expanded significantly during production, which Dean Devlin later stated that it caused him to be overwhelmed as a producer, and caused him to neglect fixing the script during production. For Roland Emmerich, he was working with a large canvas on a subject that he honestly didn’t have that much interest for in the first place. As a result, we get all of the different Roland Emmerich elements (massive destruction, hollow archetypal characters, and sophomoric humor) all thrown into a Godzilla shaped blender, where it all feels like the creation of it’s director, but not anything like what a Godzilla movie should be. Columbia/Tri-Star executive Robert N. Fried even stated that, “the team that took over Godzilla was one of the worst cases of of executive incompetence I have observed in my 20 year career.” It’s been told that studio heads didn’t even see footage of the movie until it was months away from release, realizing too late that they had a mess on their hands, making this a rare case where a movie might have benefitted from studio interference. But alas, the movie released in theaters in the summer of 1998, and quickly faded. What was especially unfortunate for Roland Emmerich is that his poor performance with Godzilla came in the same summer season where Michael Bay released his new hit, Armageddon (1998), thereby taking the crown away from Emmerich as the King of Disaster Movies. That, probably more than anything is what spurred on the career path that Emmerich carved for himself in the years after. Spending the next 20 years making one disaster movie after another, including The Day After Tomorrow (2004), 2012 (2009) and most recently Moonfall (2022), Emmerich has been trying to take that crown back.

For a time, Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla effectively killed off the giant monster movie for many years. In the decade that followed, only Peter Jackson’s King Kong (2005) remake was able to be made, and that struggled to break even on it’s own, even with Jackson riding the wave of clout after The Lord of the Rings. There was a bit of a revival when Guillermo Del Toro made his critically acclaimed action thriller Pacific Rim (2013), with giant robots fighting giant monsters. But for Godzilla himself, the rights to the character landed with Legendary Pictures, who began to devise a series of films featuring the King of Monsters as well as all the many other different kaiju creatures made famous from the original Toho run of movies. They enjoyed modest success with the first Godzilla (2014), which took a far more serious tone with the character than what Roland Emmerich brought to his film. Though the movie’s plot was still a bit undercooked, there was a lot of praise thrown the movie’s way with regards to Godzilla himself. For old and new fans alike, these new Godzilla movies felt truer to the character. For one thing, this Godzilla could actually breath fire, or more accurately atomic breath. The human characters in these movies are still hollow archetypes, but they are far more likable than the ones that Emmerich put in his film. Ultimately, Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla is a perfect case study in how not to reboot a legendary character. It’s especially a good lesson to note that when you hire a director for a movie reboot, make sure that he actually has enthusiasm for the idea of bringing new life to an old character. Otherwise, he’s just going to do whatever he feels like with the character and in the end, your Godzilla doesn’t look or act at all the way he should. This was clearly an example of a studio wanting to capitalize on a growing trend in filmmaking, which was monsters brought to life through computer animation, and having a director more interested in his own quirks failing to deliver on that fundamental action. Today, Godzilla ’98 is more of an unintentional comedy of errors given how almost none of it’s elements work together. But, the fact that the movie doesn’t even take itself seriously to begin with makes the enjoyment factor of it’s failure feel disappointing as well. Godzilla deserved much better than this, and thankfully with his more recent string of movies, the King of Monsters has managed to have the last laugh in the end, or more appropriately, ROAR.