The films and career of filmmaker Terry Gilliam are unlike anything else seen in Hollywood. Starting off as the animator and sixth member of the legendary comedy troupe Monty Python, Gilliam soon made the transition to acclaimed filmmaker, bringing along his strange and whimsical sensibilities with him in the process. Though his films are practically produced, it’s the content and stories that often set his work apart. Gilliam has a fondess for fantasy and science fiction; really, anything that delves away from the ordinary. Couple that with an absurdist and anti-authoritarian point of view, and you can easily see the common current of Gilliam’s filmography. That stong artistic style that has shaped Terry Gilliam’s film career has also made him a favorite from the Criterion company, earning some of his movies a coveted place in their collection. Although Gilliam’s filmography isn’t as extensively included in the collection as some other filmmakers, the ones that are present are certainly worthy of their placement. They also give you a sense of the director’s versatility, showcasing his ability to create modern social commentaries (Brazil, Spine #51) as well as pure fantasy adventures (Time Bandits, #37). For this article, I will be taking a look at one of Terry Gilliam’s later pieces of work; one that actually marks a departure for the director in some ways, while at the same time being an ideal presentation of his unique style. It’s his 1998 cult hit, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Spine #175). And if there were one title that has benefitted greatly from the Criterion treatment, this oddball masterpiece would certainly be it.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was adapted from the book of the same name by Hunter S. Thompson, one of the counter-culture movement’s most notorious and influential writers. The creator of what would in time be called “Gonzo Journalism,” Hunter Thompson’s style of writing has achieved legendary status. He was known for injecting his own bizarre experiences into his press pieces and for documenting the social, political, and cultural upheavals of the 60’s and 70’s with a sharp critical perspective. And one of his favorite subjects to write about was the rising drug culture in America, one in which he had very personal knowledge of. While not what you would call the most natural journalist, Thompson’s writings are fascinating nonetheless, and offer a very unique voice to an era in our history that represented significant change. That, and the fact that Thomspon was such a bizarre character have also contributed to his status as one of the great writers of the last half century. Certainly, his writings have garnered many fans over the years, including Terry Gilliam. The pairing of these two only seems natural, because Gilliam is really the only kind of filmmaker who could capture the hallucinatory nature of Thompson’s writing effectively. But, even with the way out there style of Thompson’s writing, Fear and Loathing is also strangely accessible and grounded, which is probably a result of Gilliam’s assured direction, which retains a very knowing sense of humor throughout. Strange how two oddball minds can come together and make a piece of art that is strangely coherent, but that’s what we end up with here.

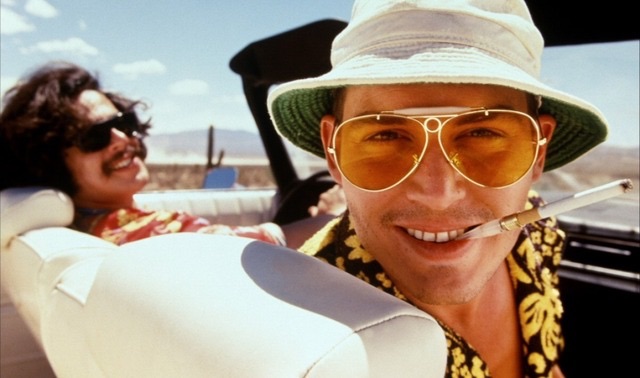

The plot itself is more or less a series of vignettes showing Hunter Thompson stand-in, Raoul Duke (an almost unrecognizable Johnny Depp) taking a trip to Las Vegas to cover a cross-country motorcycle race in the deserts outside of Sin City. With his companion and agent, Dr. Gonzo (Benicio del Toro) by his side, Duke takes in the Vegas experience while doing pretty much every drug known to man. And the different experiences are altogether trippy and hilarious in their absurdity, such as Duke envisioning the people in a casino bar as literal “lounge lizards” or both Duke and Gonzo getting high off of ether and having difficulty making their way through a Circus themed casino. Though not every moment is played for laughs, as the movie does address the downside of drug use as well. One scene involves Duke trying to talk Gonzo down from a bad trip as the dangerous addict lies in stupor in a full bathtub. Another heavily dramatic and tense scene also involves Gonzo threatening a diner waitress (played by Ellen Barkin) during a heavy late night romp. The purpose of all these stories was mainly for Hunter Thompson to document the slow burn that followed the idealism of the hippy generation, as America was slowly slipping into a post Vietnam and Watergate malaise that involved many more people turning to drug use to forget the pain of their lives. As Hunter Thompson put it, this was America’s “season of hell,” and he saw that brought out most clearly in the decadent and flashy city of Las Vegas. Though not an easy kind of story to put into a narrative, Gilliam still managed to make it work, and Fear and Loathing ends up being both an engaging set of scenes as well as an eye-opening social commentary.

The film itself had been in the works for many years, even long before Terry Gilliam was involved. The rights to Thompson’s book floated around Hollywood for two decades, with british director Alex Cox (of Sid and Nancy fame) attached to write and direct at one point. Parts of Cox’s script treatment still exist in the final version, but it is clear that the project was entirely crafted towards Gilliam’s own tastes. Though a long time in coming, the end result is a perfect display of Gilliam’s talents. Filmed in the wide 2.35:1 aspect ratio(a rarity for a Gilliam film), the movie is a beautiful trip into the bizarre mind of Hunter Thompson, capturing all the hallucinatory sights with perfect and often hilarious excess. It’s a great showcase for all of the tricks of the trade that Gilliam has at his disposal, like the consistent use of wide angle lenses to highlight his characters heightened states, or having the hallucinations come to life through puppetry and visual effects. Not only that, but the amazing cinematography by the DP, Nicola Pecorini, and the production design by Alex McDowell does a great job of capturing the sleaziness of Las Vegas in the 1970’s. You can just smell the booze and cigarette smoke that permeates every frame, and the movie makes a point to highlight the garishness of the casino and hotel rooms that these characters inhabit. Overall, Terry Gilliam proved to be the ideal person to bring Hunter Thompson’s writings to life, because only he could have the vision to make the bizarre feel so real.

In addition to Gilliam’s amazing visuals, we also are treated to great performances by the two leads. Johnny Depp showcases his abilities to disappear into a role perfectly here as Raoul Duke. Depp considers himself to this day an avid fan of Thompson’s work and the two men became well acquainted during the making of this film. Even though the character is named differently, there’s absolutely no doubt that Depp crafted his performance into an imitation of Thompson. His character work here is so spot on and is hilarious without ever being too cartoonish. I especially like the way that Depp never removes the cigarette holder in his mouth while he speaks, which becomes an indelible part of the character’s voice overall. This performance left such a mark on Johnny Depp that it wouldn’t surprise me if there are shades of Hunter Thompson in some of his later performances; I can even see just a tiny bit of it in Captain Jack Sparrow. Benicio del Toro also holds his own as Dr. Gonzo, a character that becomes a roller coaster of emotion throughout the entire film. Del Toro’s work here is especially engrossing because he shifts between being hilariously inept (like his inability to jump off a moving carousel in one scene) to being frighteningly menacing in other moments (the already mentioned diner scene). The movie works wonders when both actors share the spotlight because their chemistry is so strong. While Gilliam’s visuals take frequent flights of fancy, it’s these two that really help to ground the movie as a whole. Both of course would go on to bigger roles in the future, but even here they’re both at the top of their game. The movie also fills the cast with some great cameo appearances from many well known actors, like Tobey Maquire playing a hitchhiker or Gary Busey playing an intimidating state trooper, rounding out a strong cast of odd characters.

Criterion usually has to put a lot of work into their restorations, but in this case, the film already was given to them in a mostly printine state. Such is the case with movies made in the last several decades that make it into the Criterion Collection. That’s not to say that Criterion transferred the edition with a lazy effort. The movie was given the best possible visual treatment on blu-ray as always, capturing all the visual flourishes of Gilliam’s film the way they were intended to be seen. Gilliam’s movies in particular are defined by their distinctive color schemes, and Criterion thankfully makes those colors pop in high definition. In particular, the brownish hues of the nearly washed out desert scenes really retain a consistent quality to them, and they contrast perfectly with the darkly lit and almost sickly hued hotel scenes. The audio presentation is also strong, capturing the sometimes hallucinatory nature of the soundscape in this movie. Though not a sensory overload experience in the audio department, there is nevertheless a lot of creativity in the sound mix, which the blu-ray presentation perfectly presents. It helps when the filmmaker is readily available to approve the quality of these presentation, and of course the edition is marked with Terry Gilliam’s seal of approval. Again, not a revelatory audio and visual presentation by Criterion, given that the edition had to work with some already well preserved elements, but it does represent the solid efforts that they put into every title, whether old or new.

The supplements are pretty healthy as well for this edition. First of all, the artwork used on both the outer cover as well as in the insert booklet help to give this edition a lot of character on its own. Provided by artist Ralph Steadman, the artwork perfectly stylized the movie with often bizarre illustrations that perfectly compliment the film you are about to watch. The features themselves include no less than three commentary tracks; one from Terry Gilliam, another with Johnny Depp and Benicio del Toro, and even one from Hunter Thompson himself. Deleted scenes are also included with commentary from Gilliam. Most are fascinating to watch, especially since they show different elements of the actor’s performances, but it’s clear why many of them were cut, which is explained well enough by Gilliam. Another fascinating feature is a collection of correspondence written by Thompson over the course of the film’s making, all read aloud by Johnny Depp. It’s a treat to listen to Depp add more to his performance as the character, but it also offers an interesting insight into Thompson’s own experience during the the making of the film. A couple of short documentaries are also included, called Hunter Goes to Hollywood and Fear and Loathing on the Road to Hollywood, which delve deeper into the long development of this movie. Another documentary also comments on the controversy surrounding the final script, when it changed hands between Alex Cox and Gilliam. Other materials include an excerpt from Fear and Loathing’s audio CD, trailers, production stills, and rare materials about Oscar Zeta Acosta, the real life inspiration for Dr. Gonzo. Overall, a very packed edition for a movie deserving of such a treatment.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is a great oddball film experience and I’m glad Criterion saw it worthy of their film library. It didn’t take long for the film to make it into the Collection (just five short years after its premiere) which goes to show just how strong an impact the movie has left on audiences. Though not a box office success when first released, the movie has amassed a strong cult following, one in which this Criterion edition is clearly aimed at pleasing. I for one enjoy this film immensely, mostly as a showcase for Terry Gilliam’s style and for the stand out performances of Johnny Depp and Benicio del Toro. As far as Hunter Thompson goes, I don’t prescribe to his sense of nostalgia over the drug culture of 60’s and 70’s, but I do admire his unique style as a writer. He was a one of a kind character and a unique voice in American pop culture. After his unfortunate suicide in 2005, his legend has continued to grow and this film marked a great entry point for anyone looking to see what made him stand out so much. But, even apart from it’s connection to the legendary author, the movie still stands as a unique cinematic experience. Terry Gilliam is a welcome visionary in the Criterion Collection and it’s surprising that his work is not more widely represented; something that is going to be partially remedied when Criterion adds The Fisher King (1991, #764) later this year. But if you’re looking for a unique film that showcases the director’s talents well, then give this Criterion edition a look. But don’t stay too long. This is bat country.