Animation is a remarkable, yet time consuming art-form. When audiences see a new animated film in their local theater, I’m sure that very few of them ever think about the time and money that was poured into their completion. With changing technologies, that extensive time frame has shortened somewhat, but even Computer animated features can still take years to be completed. Back in the Golden Age of animation, you would sometimes be looking at 5 years or more for the production of a full length feature, from concept through production, to locking it in the can. Towards the end of the heyday of hand drawn animation, 4 or 5 years was commonplace, though it would fluctuate between a very short (2.5 years for Beauty and the Beast) and very long (6.5 years for Sleeping Beauty). But, what about 31 years of production? That was the case with a little seen but highly regarded animated feature called The Thief and the Cobbler (1995). The magnum opus and work of passion for independent Canadian animator Richard Williams, Thief not only carries the longest production span of any animated film ever; it holds the record for the longest film production, period. And in fact, it could be argued that the movie is still not done, depending on what version of the film you are watching. I briefly mentioned this movie in a previous article about prolonged film developments and felt that it was deserving of a analysis all it’s own. The Thief and the Cobbler is a movie that has fascinated me recently as an animation fan, not so much for the movie itself, but for the fascinating history of it’s production. In Thief, you see not just a fascinating work of pure artistic passion on display, but a document to the history of animation itself.

To know something about this movie, you need to know a little about the mad genius behind it. Richard Williams is a veteran of the animation medium, and is widely considered within the industry to be one of the great masters. Though he had for many years been courted by major animation studios like Disney and Warner Brothers to jump on board their teams, Williams has largely preferred to work independently through his small London, England based studio. From there, he has largely made a name for himself as a highly respected commercial and title sequence producer. His work can be seen in the opening titles of 60’s and 70’s era classics like What’s New Pussycat? (1965) and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), as well as in classic British television commercials from the era. What made his work stand out was the intricate and fluid detail that he would put into his animation; utilizing complexity that few other studios would ever attempt. In 1971, legendary animator Chuck Jones commissioned Williams’ studio to create a short adaptation of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and the result was a critically acclaimed success. Originally intended for television, Carol was subsequently given a theatrical run, which led to Oscar win for Williams and his team. From that, he was given an even bigger commissioned assignment to create a film centered around the Raggedy Ann & Andy dolls. True to Williams style, Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure (1977) is an animated film unlike any other you will ever see; with bizarre and often surreal sequences that defy explanation, and not what you would expect for a movie based of rag dolls. But, Williams career is most defined by his life’s work, The Thief and the Cobbler, a movie that sadly became too big a dream to hold onto.

The Thief and the Cobbler began in 1964 as a collaboration with Middle Eastern author Idires Shah, who collected and translated many Arabic tales about a character called Mulla Nasrudin, or “the wise fool.” When the partnership between Williams and Shah broke down, Williams retained the idea for the project and changed the “wise fool” into the character that would eventually be the titular Thief. Later, Williams began another go at developing the project in earnest with a new treatment by screenwriter Howard Blake. Blake’s treatment brought many elements that would turn up in the final film, including the titular cobbler named Tack, the evil vizier Zig Zag, the sleepy king, and the plot device of the Three Golden Balls that protect the Golden City. Though the script helped to bring structure to the story, Williams maintained a free-flowing style to his direction. Instead of story-boarding out his scenes, he instead opted to let scenes play out based on the imaginations of himself and his artists. This unfortunately led to a lot of sequences that added little to no momentum to the plot, though they stood out as remarkable on their own. Williams also insisted on animating the sequences in 24 frames per second, as opposed to the industry standard of 12 frames. The result gives the animation a remarkably smooth flow, which becomes mesmerizing the longer the sequences run; which sometimes can be several minutes without cutting. And that in lies why it took 20 years to only complete 20 minutes of the planed 100 minute movie. And because of this sluggish adherence to free-flowing storytelling and complex animation that Williams was hard pressed to find funding for so long to complete his master work.

Over time, William’s studio managed to stay afloat with projects like Carol and Raggedy Ann & Andy, but Thief was always waiting in the wings for when the opportunity came. Due to mounting economic pressure, Williams constantly had to simplify his story and cut back on his animation, but he still persisted with his bold vision. Sometimes, he lucked out with an interested investor. In the late 70’s, 15 years since the start of production, Williams caught the attention of Saudi prince Mohammed bin Faisal Al Saud, who commissioned an animation test to see if the remainder of the film was worthy investing in. Williams used this influx of funds to complete what would end up being the film’s most complex scene, the destruction of the colossal War Machine from the villainous barbarian King One-Eye, a sequence that to this day is mind-boggling in it’s complexity. Though the prince was impressed with the work that Williams had done, the cost overrun and missed deadlines prevented further investment, and Williams was forced yet again to shelve his dream project, although now with perhaps the most elaborate sequence finished. Though unseen by the public, Willaims was still able to share what he had done to other industry professionals who had nothing but high praise for what they saw. Eventually, Disney sought Williams assistance with one elaborate project of their own; the Robert Zemekis directed Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988). What Willaims revolutionized at his studio was multi-perspective animation, where character and environments would constantly change perspective as the camera placement swoops around, giving them an almost three-dimensional look. Naturally, Disney wanted this style to help their hand-drawn animated characters like Roger and Jessica Rabbit co-exist believably in a live action film, where camera movement is ever-changing. Williams was named Animation Director for the film, and his work again garnered him an Honorary Oscar.

With the goodwill from Roger Rabbit, Richard Williams finally had the attention of Hollywood, and plenty of interested parties lined up to give Williams the needs to finally finish Thief for good. Disney and Steven Spielberg, the parties behind Roger Rabbit, expressed interest at first in funding the project, but later backed out. Warner Brothers stepped in and signed Williams to a contract. With that, he had the money and the manpower to complete his film, as well a release schedule that he had to adhere to. He was finally able to have over an hour of completed film, but again, his adherence to perfection caused to project to go over-budget and over-schedule. Sadly, at the same time, Disney was themselves working on their own Arabian set animated feature, Aladdin (1992), which made Warner Brothers all the more impatient and worried. Unfortunately, Williams darker and more adult-appealing film was less marketable than Disney’s blockbuster, and Warner became certain that they had a film that was un-releasable. So, they cut their contract with Williams and ended up selling it to a secondary animation studio run by Fred Calvert in order to complete it, without Williams involved. Williams tried to salvage what he had with a 1992 workprint screened for studio execs, but it didn’t work. Thirty one years since the first drawing had been completed, The Thief and the Cobbler was released to little fanfare in 1995 with nearly half of Williams original film either cut or re-animated, with a new Disney-style musical score and celebrity voices cast for his originally mute title characters (Matthew Broaderick as Tack the Cobbler and Jonathan Winters as the Thief). Vincent Price, who recorded his voice for the villain Zig Zag over the 30 year span, was retained, but because the film released after his 1993 death, his lines ended up getting cut down rather than replaced. Miramax oversaw the release in North America, and this compromised version has since become known as the “Miramax Cut” even though they had nothing to do with the production.

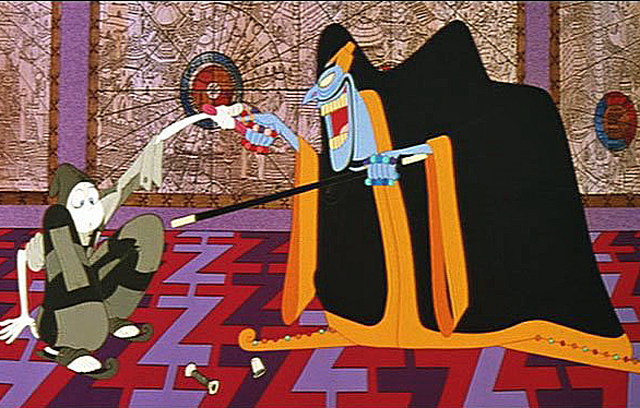

Thus, the long, troubled production of Richard Williams masterpiece came seemingly to an end, with his vision never being fully realized. He came close, but studio interference caught up to him in the end. Regardless, Williams is still regarded as a legend among the animation community and Thief surprisingly has something to do with that. Because of it’s long production, Thief stands as somewhat of a documentation of the evolution of animation, bridging the Golden Era with the Renaissance of the late 80’s and the early 90’s. Think about it, in the time it took Thief to be completed, Disney Animation had put out 15 feature films, and had seen their studio both decline and be reborn under new management. Walt Disney was still breathing when production started on this film, just to give you an idea of how far back this project began. Animation as a whole changed so much in that time, and you can see that reflected in the movie. While Williams attention to detail remains fluid throughout, you can spot instances when the quality differs. The sequences that were animated late in production have a different, more polished look than others that were made decades earlier. The older scenes, mostly centered around the Thief, have a more classical look to them, not unlike many of the trippy, psychedelic animated films that arose in the 60’s and 70’s. Couple the sequences where the Thief tries to steal the magical Golden Balls and the climatic War Machine sequence at the end, and it’s clear that they were made in different eras, where different tools were made available to animators. At the same time, Williams staff of animators also shows a remarkable span of animation history. He brought onto his team some legendary animators like former Disney animator Art Babbit (who worked on the Queen in Snow White and Geppetto in Pinocchio) and Grim Natwick (the creator of Betty Boop) to not only contribute their own animation, but also to mentor both him and his young staff. And among his young staff were newcomers like Andreas Deja and Eric Goldberg, who would go onto prosperous careers at Disney, including working on films like Aladdin (animating Jafar and the Genie respectively).

In addition to it’s legacy of reputation and the quality of it’s talent, The Thief and the Cobbler also is a perfect illustration of how just how difficult it is to get a movie made. Not every studio has the financial security and resources of Disney. And Williams never wanted that either. He knew that he would never see his vision realized in a corporate controlled environment, so he continually sought to keep his production as independent as possible. He stated very early on that his movie was going to be very non-Disney, both in the animation and in the story-telling. No songs, no animal sidekicks; just pure visuals transporting the viewer to a world never seen on screen before. Sadly, when corporate interests did intervene, it turned the movie into exactly what Williams was trying to avoid. In that regard, the “Miramax” cut stands as a cautionary tale of when studio interference spoils the finished product. Williams’ workprint has resurfaced over time and has been circulated online in various forms. Williams himself has managed to put the disappointment behind him and moved onto other projects, though the movie is still a sore point to this day. Dedicated fans however have done extensive work to try to reconstruct William’s original version. Roy Disney, Walt’s nephew, even tried to get a restoration off the ground before his untimely death in 2009. Other fans have shared their own work online in what is now known as the “Recobbled Cut.” This version shows William’s original intent with unfinished, work-in-progress scenes inter-cut with finished ones from the Workprint. Though in rough form, it nevertheless shows us what might’ve been. What’s fascinating is that it shows that animated films are ever completed in sequence, but are often done out of order, with the more complex scenes done first. In the recobbled cut, we see that many of the unfinished parts are the filler moments in between the more epic scenes. Thankfully, Williams brilliance shows in the film’s spectacular finished moments, like the War Machine, the chase through the palace, the villain Zig Zag’s grand entrance, and the polo game with the Thief caught in the middle. We may not have a finished film, but these big moments allows our imagination to fill in the rest.

Richard Williams, now 84 years old as of this writing, is still working on new projects today. He most recently completed an entirely hand-drawn short called Prologue (2015) which takes many of the techniques he pioneered with Thief like hyper-detailed character animation and three-dimensional perspective changes, and presents them in a stripped back, pencil sketch presentation. Again, this was another labor of love that he worked on for years, even while he was still making Thief, and his efforts were rewarded with yet another Oscar nomination. Though, he’s moved on from Thief, he still hopes that someday it will see a new life, and maybe even completed based on his original vision. A screening of Thief in 2013, based off the Workprint with a new high-def restoration, won wide praise from the animation community, and Williams is once again embracing the film, incomplete as it is, as his most cherished work. For those of you interested in seeing the movie, avoid the compromised “Miramax Cut” and find one that is closer to Williams vision. Sadly, the Miramax version is the only one available on home video, but, the makers of the Recobbled version have graciously made it available to view online for free. In fact, I’m linking it for you all to enjoy below this article, because I want as many people as possible to experience it. It’s not perfect, nor is it among my favorite animated films, but as a fan of animation, I admire it as a work of un-compromised artistry. It’s also a fascinating look into the creation of an animated film, with so many sequences in various stages of completion. Whether or not we see a finished version of this one day is unclear, and it’s highly likely that it may never be complete, but for now, we can appreciate what 30 years of a persistent artistic vision can accomplish. In this movie, you see the story of the animated medium played out in one place, with artistic styles of several eras all coming together at once and creating something special. And whether people know it or not, it has influenced a whole generation of artists in the years since. In the end, it’s the animated equivalent of a Venus de Milo; more powerful broken apart than it would’ve ended up being as a whole.

PART 1

PART 2

PART 3

PART 4

PART 5

PART 6

PART 7

RICHARD WILLIAMS INTERVIEWS