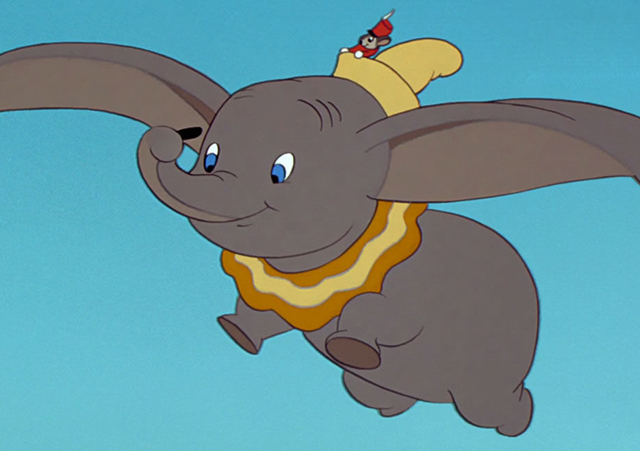

For a lot of people, when they think of a Disney film, they first thing that will pop into their mind will be a fairy tale. Make no mistake, whenever we look at a point in their long legacy of films, the ones that prove to be the most pivotal in the course of Disney’s success have almost always been centered around princesses and shiny castles. Of course there are exceptions among their biggest hits being separate from the formula, like 101 Dalmatians (1961), The Lion King (1994) and Zootopia (2016), but you look at all the biggest eras of Disney’s history and there’s almost always a fairy tale attached to it. They of course started off with a classic fairy tale with Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937), but the the other eras would end up getting their own movies to help shape the direction of the company; the post-War golden era had Cinderella (1950) and Sleeping Beauty (1959), the Renaissance Era had The Little Mermaid (1989) and Beauty and the Beast (1991), and the Digital Era has had Tangled (2010) and Frozen (2013). But, it could be argued that the most crucial film to the history of Disney Animation was nothing that you would have expected. It was neither a safe bet fairy tale, nor a bold experimental picture that redefined the artform. Instead it was a little side project that slipped under the radar only to become an unexpected phenomenon. That movie was a fable about a little baby elephant named Dumbo. Dumbo (1941) the movie may not immediately pop out as something special in the Disney canon. At a scant 64 minutes it is one of the shortest films Disney has ever made, barely cracking the hour mark. It also doesn’t feature the same kind of groundbreaking animation that it’s loftier predecessors (Snow White, Pinocchio, and Fantasia) had. So, why is Dumbo so crucial to the history of Disney Animation, and to animation in general. Because, it turned out to be the movie that saved Disney from economic collapse which could have led the animation giant to bankruptcy. Without Dumbo, Disney Animation would have died on the vine after one of the most meteoric rises in Hollywood history.

For a little historical perspective, here is how Dumbo came to be Disney’s unlikely savior. After Walt Disney broke all box office records with his huge gamble of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, the first ever feature length animated film, he not only was able to pay off all of his outstanding debts, but he now had a large sum of profit to cash in on. With the money made from Snow White, Walt and Co. moved from their Los Feliz based studio to a brand new and much larger studio lot in the San Fernando Valley. Situated a stone’s throw away from other major studio lots like Warner Bothers and Universal Studios in a burgeoning little community called Burbank, Walt Disney had a base of operations that now gave him the space to grow his company further and give his employees the most state of the art amenities. Of course, once the move was made, Disney quickly put his men to work on what would be the ambitious follow-ups to Snow White. And by ambitious, I also mean expensive. When Snow White was completed, it had a then staggering $1.7 million dollar budget, and that’s in Depression Era dollars. Today that number would easily clear the 9 digit mark. Pinocchio (1940) and Fantasia (1940) combined were nearly five times Snow White’s budget, and that’s not counting the amount of money spent on building the new studio. Now, for Walt at the time, the expensive investments were worth it, because he had the wind in his sails from the success of Snow White. Pinocchio would be an artistic achievement on par with Snow White, and Fantasia was anticipated to redefine the definition of cinema all together. But, something would end up dashing Walt’s dreams; one which was entirely out of his control. The outbreak of war in Europe after Hitler’s invasion of Poland almost immediately shut off the much needed European box office grosses that Hollywood studios depended on, including Disney. With Pinocchio and Fantasia still in the pipeline and facing that brick wall of a war torn international market, the Walt Disney company that was once flush with cash was now suddenly thrust back into deep debt. Half a year into the war in Europe, Walt quietly released Pinocchio into domestic theaters in February 1940, and while it performed well in America, the grosses were still well short of the film’s budget costs. Fantasia performed even more poorly, having been hampered by it’s limited roadshow release, where it could only play in theaters equipped for it’s revolutionary surround sound. Just as quickly as Walt Disney’s star rose, it had quickly fallen back to Earth.

So, what was Walt going to do? He began to assess what he still had in the pipeline and wonder what he was capable of moving forward with. The other expensive project that had already been put into production, Bambi (1943), was put on pause, and Walt also made the crucial decision to axe projects altogether like his first attempt at The Little Mermaid and a feature project that would end up becoming the short, Mickey and the Beanstalk (1947). To make matters worse, the Disney studio also found itself embroiled in an animators strike, one in which Walt’s fiercely anti-Communist stances inflamed the situation to a boiling point. With no money coming in and seeing himself loosing control over the staff at his studio, Walt was in a dire situation that he honestly had no way out of. All the studio could afford during this time of contraction were safe bet short cartoons. That was until a couple of members of Walt’s story department team came forward with a modest sized feature idea. Dick Huemer and Joe Grant were two story veterans at the Disney studio, and had just come off their work of crafting the concert format for Fantasia. They brought to Walt’s attention a children’s book from authors Helen Aberson-Mayer and Harold Pearl. In it was a story about a baby elephant born with giant ears. The baby elephant gets teased and humiliated for his abnormality, until one day he begins to flap his enormous ears and suddenly takes flight. After this extraordinary event, the little baby elephant is treated like a star after he has shown that his oddity is really a gift. The heartwarming story of overcoming adversity and showing one’s true worth appealed immediately to Walt and he agreed to have the story of Dumbo the Flying Elephant launched into production. However, due to the budget constraints at the time, Dumbo would not have the luxury of the same kinds of lavish budgets that Pinocchio and Fantasia had. Huemer and Grant had to do what they could with the miniscule budget that was allowed to them. And this constraint in some ways proved to be an unexpected blessing of it’s own.

Walt, unlike with his other movies, was very hands off in the making of Dumbo, obviously because he was dealing with financial troubles and the strike at the time. So, Dick Huemer and Joe Grant were granted an unprecedented amount of creative freedom. Dumbo was very much a change of pace for the studio, focusing more on story than showing off the possibilities of it’s animation. Most of the movie’s brief run time involves Dumbo moving from one ordel to another in a very sparse story of learning to survive in the harsh environment of a Circus. Where the filmmakers found the heart of the story is in Dumbo’s relationship with his mother, who is taken away from him early on. With that as the central focus of the film, they were able to craft Dumbo’s story around a motivation that would encompass why he sets out to do what he needs to do. And that includes being humiliated by the clowns, suffering the rejection of his fellow elephants, and eventually his drunken descent into self realization. Huemer and Grant needed to keep everything tightly controlled on their film in order to meet the budget demands. One way they accomplished this was by simplifying the art style. Prior to Dumbo, Disney films were lavishly detailed, with background art especially showing un-paralleled intricacy. Dumbo would be far more simplistic, but that was actually to it’s advantage. Instead of having backgrounds painted like grand masterpieces, Dumbo had backgrounds that were painted in watercolors, with detail limited to sometimes mere abstraction. In some scenes, the characters aren’t even animated against a fully painted background, but instead are simply shown in front of a single toned splash of color, including all black. Character models were also simplified, with most of the characters in the movie being the easier to draw animals and the harder to draw humans often shown partially out of frame or silhouetted with shadows. For a children’s storybook narrative like Dumbo, this art style actually feels in character with story, because the movie looks like a storybook illustration come to life.

But, the creative freedom also allowed for Huemer and Grant to do things that were never allowed before in a Disney movie. The movie has some wild, abstract ideas brought to life that help to make the story feel more epic than it really is. A spectacular sequence involving circus elephants forming an acrobatic living pyramid is such a bizarre idea in concept that it allows for the animators to truly go wild in bringing it to life. It especially becomes a highlight in the final movie once everything goes wrong afterwards. But, that sequence is nothing compared to the film’s most famous sequence; the Pink Elephants on Parade. This is where the Disney animators completely throw every rule out and just go wild in ways they would never have been allowed to before. It’s interesting to note that at the time of Dumbo’s making, Walt was beginning a collaboration with none other than famed artist Salvador Dali. Dali was brought to Disney with the intention of creating a surreal animated short called Destino, which Walt intended as an addition for Fantasia in it’s original revolving program concept. Despite some promising early development, including original artwork by Dali that still survives to this day, the project was shelved after Fantasia’s failure at the box office, after which Dali returned home to Spain. But, while Destino didn’t get made, it still had an influence on those still working on Dumbo, and you can definitely see the Salvador Dali affect in the Pink Elephants sequence, including the artist’s famous obsession with eyeballs. The sequence is so out of left field for Disney, and yet it works for the film. It’s one of the first historically interesting brushes that Dumbo had with history, as one of the 20th century’s most famous artists directly influenced it. What’s even better is that the abstraction of the sequence also helped the animators create something artistically daring without blowing up the budget. Most of the Pink Elephant sequence is cast against all black backgrounds, making the sequence surprisingly cheap to produce. All of this helped to make Dumbo a movie that felt in line with Disney’s most ambitious films, while at the same time costing only a fraction to make.

That careful planning as well as an appealing story at it’s center made Dumbo a perfect reset to help Disney right the ship in troubled waters. Even with the animator’s strike slowing things down, Dumbo managed to be completed in less than a year, which is unheard of for an animated feature. Walt’s lack of involvement may have also sped things up, as the filmmakers were less tied down by Walt’s numerous notes during the making. The film completed in a hurry as Walt embarked on a goodwill tour of Latin America on behalf of the U.S. State Department, who were hoping to cut down on the influence of Axis powers in their neighboring countries. While Walt was away, his brother Roy brokered an agreement with the animators union and the strike came to a quick end. With the turmoil behind them, Disney Animation was set to give Dumbo a proper premiere. Though still dependent on the domestic market to gain a profit, hopes were still high that Dumbo could help the struggling company out. The film released finally in late October 1941, and became an instant smash hit. Audiences really resonated with the lovable little elephant who learned to fly. Though the movie left audiences spellbound with it’s more dynamic moments like Pink Elephants, it was it’s heart wrenching story that truly helped it receive high marks. The New York Times critic Bosley Crowther wrote that the movie was “the most genial, the most endearing, the most completely precious cartoon feature film ever to emerge from the magical brushes of Walt Disney’s wonder-working artists.” Most other critics also praised the movie with likeminded flourish. The movie itself also opened strong at the box office, nearly making up it’s minimal production budget solely through the domestic box office receipts. What this showed was that Disney could indeed survive without having to break the bank with each feature and still maintain their artistic integrity. Certainly Walt preferred to be more lavish with his films, but the success of Dumbo couldn’t be denied. Dumbo was more than just a hit, it became a phenomenon. Everyone was suddenly talking about this little elephant who could fly and even the media elite began to take notice. Dumbo was selected by Time Magazine to be featured on their cover as Mammal of the Year for their December 1941 issue; a high honor at the time, and unprecedented for a cartoon character. However, that promise of a cover on Time Magazine never came to be and that is because of Dumbo’s other significant brush with history.

On December 7, 1941 a moment that would live in infamy occurred. The Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor and America in response was put on a war footing. After sitting out the conflict that was going on in Europe and Asia over the last two years, the United States could no longer ignore the spread of fascism across the world, and officially entered World War II. Naturally, this pushed Dumbo off the front cover of Time Magazine, as the proclamation of war took precedent. The publication did eventually run their profile of Dumbo in a later issue, but the front cover was scrapped before it was ever drawn up. Naturally, there was worry that the war at home would cut into Dumbo’s future grosses, but the opposite proved true. Americans needed an escape from the worries of the oncoming war, and Dumbo was the exact pick-me-up kind of entertainment that they desired. The movie continued to play very well into the next year. Even as Disney’s next feature Bambi was released and quickly underperformed, the grosses from Dumbo helped to keep the studio from loosing more ground. Knowing the effectiveness of Disney’s studio being able to connect with a wide ranging audience thanks to a movie like Dumbo, the U.S. war department contacted Walt to propose using his studio to make propaganda films and artwork to help promote the war effort. Though Walt was not reticent to hand over his studio to a higher power, he nevertheless agreed because he too believed in the wartime cause. Though it limited what Disney was allowed to make, the propaganda machine run by the Government nevertheless helped to keep Disney solvent all the way through the War years, and helped him recoup quicker from the financial burdens of the past without having to loose the profit gains from Dumbo. During those war years, Disney managed to keep his studio running, with his artists churning out adverts, insignias, and short cartoons all with their famous characters promoting the war effort. Dumbo in fact became a favorite of the air force, as some pilots even painted Dumbo on the sides of their aircrafts, making him a sort of unofficial mascot. When the war ended, Walt took back control of his studio and began to plan for his post-war future. Eventually, when the 1950’s rolled around, Walt saw a new opportunity emerge to present his film, which was television. In 1954, he premiered his prime time TV series Disneyland, which he himself hosted personally. In addition to original programming on the show, Walt also used Disneyland to run some of his classic films, albeit shortened for commercial time. And what was the first film to be given the honor of a television premiere? Dumbo of course. From the beginning of World War II to the prosperous days after, Disney could always rely on Dumbo for an extra boost when it needed it.

Now 80 years later, Dumbo’s legacy is still going strong. He’s an evergreen presence in the parks, with a famous spinning ride made in his honor. Upon a visit to Disneyland, Democratic candidate for president Adlai Stevenson famously refused to go on the Dumbo ride because the elephant is a symbol of the Republican party. Despite that benign little political anecdote, Dumbo has not been without controversy over the years. Most famously, the movie has come under fire for it’s racial controversies. Dumbo befriends a group of crows in the film, all of whom help to convince him that he can fly. Sadly, it’s unmistakable that the crows are caricatures of black people, and not necessarily in a flattering way. Many civil rights groups have called out Disney for this depiction, and their complaints are not unwarranted either, especially when you learn that one of the crows has the name Jim Crow; a very bad pun in retrospect. Like most of old Hollywood depictions of minority characters, the extant of the offense is really up to discussion of intentional malice, which I don’t think the Disney artists were intending, as it was just how most movies at that time often portrayed black characters. Indeed, the message at the center of Dumbo is tolerance, as Dumbo overcomes his abnormality to prove his worth. It’s illustrated especially well in how his best friend turns out to be a mouse named Timothy, a reversal of the normally adversarial relationship between the species shown in media. Also, Dumbo is accepted as part of the crow’s group, themselves socially outcast, and like them Dumbo achieves his true self by learning to fly. Still, the controversy around the film should not be dismissed as the hurtful depictions of black people in film needs to be discussed. There was worry that the offensive part of the film might have been excised from the movie altogether for Disney+, which thankfully didn’t happen, especially when it has one of the best songs in the movie. It’s better for American society to have the ugly parts of history exists alongside the good so that we can learn from it, instead of burying the parts we don’t like. Something Disney should consider with Song of the South (1946). Dumbo‘s place in the Disney canon is truly unique, because had it not salvaged Disney when it did, who knows if Disney would’ve made it through the war years unscathed like it did. Would Disney have still been deep in debt had Dumbo not given them a boost? Would they have failed to recover in order to gain their second wind that guided them into their Golden Age? Would Disney have had the confidence to take on more costly chances like Disneyland? There’s no denying that things were precarious before Dumbo, and it became an unlikely champion that helped to set things back in order. That’s largely due to a rock solid story crafted by Dick Huemer and Joe Grant, as well as an unburdened team of animators who were granted more creative freedom. Even to this day, it’s hard to find another animated movie that so effortlessly tugs at the heartstrings like it does. Dumbo is a jewel is a worthy jewel in Disney’s animation crown, and like the tiny elephant at it’s center, it sours much higher than anyone would’ve expected it to.