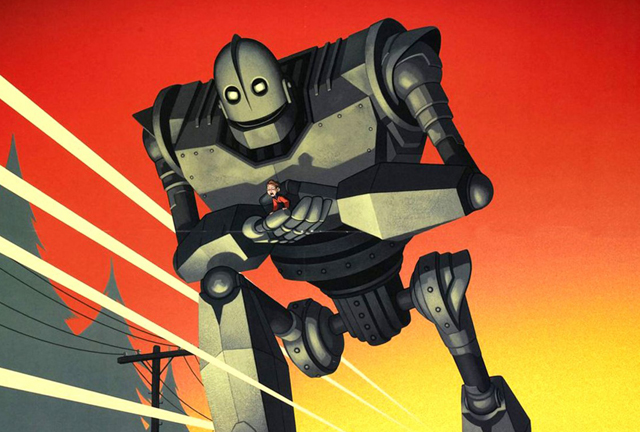

When people discuss the years that are considered among the best ever for movies, probably the most recent one to come into that conversation would be the year 1999. Closing out the 20th century as well as the last millennium with quite a bang, we saw a year that banged out one classic after another, many of which have gone on to be highly influential 20 years later. But the interesting thing about 1999 is the fact that so many of the best loved movies from that year were ones that at the time were not major hits upon release. I already spotlighted one of those movies a couple weeks ago with my retrospective on Brad Bird’s The Iron Giant here. I myself in particular have really found the legacy of these rising classics particularly interesting, because they go all the way back to when I started paying closer attention to the movie industry in general. In 1999, I was a sophomore in high school who had just seen Lawrence of Arabia on the big screen and knew that my life’s path was going to be in the pursuit of film-making. Because of this renewed interest, I began expanding my range of films to look out for, trying to open my perspective to include a wider spectrum of what the industry had to offer. And in the early fall of 1999, I managed to catch a movie that not only hit the right spot, but would go on to become the first movie that I ever proclaimed to be the best movie of the year, since this was also the first year ever that I began to keep track of that distinction. That movie would be the shocking, “in-your-face” spectacle that was David Fincher’s Fight Club. Fight Club knocked me off my feet the first time I ever watched it, and even 20 years later it still packs a punch. But the interesting I discovered while revisiting it was how different it plays today than it did back then. The movie still holds up, don’t get me wrong, but the message takes on a whole different meaning in today’s cultural climate.

Much like The Iron Giant had in the weeks prior to the release, Fight Club was not financially successful right away. It didn’t bomb as heavily as Giant did, since it was not a terribly expensive movie to make, but it still underwhelmed, given that it had an A-list star like Brad Pitt on the marquee, as well as two rising, Oscar-nominated names like Edward Norton and Helena Bonham Carter involved as well. Critics were even divided at first. Roger Ebert notably gave the movie a thumbs down review, stating that he found the movie an unfocused mess. But, as with most movies that become classics long after their initial theatrical release, Fight Club found it’s audience on home video. Fight Club came out at just the right time to take advantage of this new technology called DVD, and it was the first cult hit to rise on this new format. In time, the movie became a best-seller and critics were starting to change their tune. For a lot of people, the movie was a revelation, as well as a breath of fresh air after a decade of polished, studio fare. Like it’s fellow 1999 alum, The Matrix, Fight Club brought a notably punk style to the medium of film; changing the way movies looked, sounded, and even edited. But while The Matrix had a sleek cyber-punk aesthetic to it, Fight Club was grungy, dank, and even rotting at the edges at some points. It was a movie that was held nothing back and presented a decidedly anti-Hollywood aesthetic to the big screen. And a lot of people started to ask themselves; is this movie the future of film-making? Is this the start of an American New Wave? Did Meat Loaf actually give an awards worthy performance in a movie? No matter what anybody said then or in the years after, Fight Club had left a mark on the film industry.

Perhaps one of the things that really started pulling in new people to the movie was the unexpected way it played a trick on it’s audience. Again, the year 1999 had many noteworthy things that left an impact on audiences, but one that really stood out was the renewed popularity of the plot twist. M. Night Shayamalan had earlier that same year stunned people across the world with his now infamous twist ending to The Sixth Sense, helping to propel that film to record breaking success. But, at the same time, Fight Club had it’s own shocking plot twist that in some ways is even better executed than Shayamalan’s. Had The Sixth Sense not taken so much of the thunder away in the weeks prior to Fight Club’s release, I wonder if the revelation in Club may have hit harder than it initially did. For those of you who haven’t seen the film and don’t know what I’m talking about, well fair warning, but there are SPOILERS ahead. The plot centers around a nameless protagonist known only in the credits as the Narrator (played by Edward Norton). After a rough couple of weeks of working a thankless job and going to therapy, he runs into a quirky gentleman on a plane ride home named Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt). After the Narrator’s apartment burns down, he crashes at Durden’s run down home in the bad part of town, and the two come up with a crazy way of letting out some of their aggression; they begin to fight each other. In time, other people want to join in and both the Narrator and Tyler start what ends up becoming known as the “Fight Club.” Over time, the Club becomes bigger with Durden making more demands of it’s members to declare their loyalty to the group, creating in away a cult like organization. This troubles the Narrator who desperately tries to reverse the zealot like direction this club is going in. But, in his efforts, he finds that he can no longer reach Tyler and the Club has transformed into a full on terrorist organization, all of whom look to him as their leader. And then we get the bombshell. The Narrator cannot locate Tyler Durden, because he is Tyler Durden. The Tyler we’ve seen is just an imaginary friend that has manifested through the Narrator’s paranoid schizophrenia, and with that, the movie reaches it’s legendary peak.

The plot twist stems from the original novel of the same name from author (and fellow Oregonian) Chuck Palahniuk, but it’s execution is so well handled by director David Fincher and screenwriter Jim Uhls. For nearly two-thirds of the movie, you have to buy into the belief that Tyler Durden and the Narrator are two different people, and not two personalities in one body. The excellent chemistry between Edward Norton and Brad Pitt sells that dynamic perfectly, and you just have to admire the fact that the movie expertly keeps you in the dark until the bombshell drops. But that’s not the only thing that makes the movie a classic. This movie, probably more than any other, cemented the Fincher style. David Fincher had won acclaim four years prior with the unforgettable thriller Seven (1995), and was able to deliver a compelling drama with The Game (1997). But with Fight Club, we saw Fincher really begin to play around with the camera, utilizing CGI for the first time, which he pushed to the limit with what was possible in 1999. This was the first movie where Fincher started using his high speed pans, which would take the camera across the plain of view at such incredible speeds and through impossible barriers that could never be done with a standard camera (like through concrete walls or even something as tiny as the ring of a coffee mug). Such a technique has since become David Fincher’s signature, and it put him on the map as a filmmaker. The movie also defies many cinematic conventions, like several points where it breaks the fourth wall, and reminds you that you are indeed watching a movie. There’s a great moment where we see Pitt’s Tyler working as a movie projectionist, and while he is working with the Narrator speaking directly to the audience about what a projectionist does, Tyler points to the point of the screen to the reel marker appears just as it flashes on screen, referring to it as a “cigarette burn.” When I became a projectionist myself in college, you can bet that I called those markers cigarette burns as well. And it’s that free-wheeling sense of anything goes that made Fight Club so appealing to a young, blossoming film buff like me back in 1999. Indeed, watching it only gain in popularity over the years has been very satisfying as someone who took to it so strongly from the very beginning.

But, after 20 years since it’s initial release, it’s interesting to see how differently it plays now than it did then. In 1999, the world was a much different place than it is today, and it’s amazing to re-watch the movie in 2019 and see how far ahead of it’s time it was. There are some things that both the novel and the movie couldn’t have foreseen, like the rise of social media and the radicalization of fringe political movements, but given how so many elements of the story feel so relevant today, it’s really amazing to see how prophetic Fight Club actually is. Some would argue that Fight Club is actually partially to blame for some of the discord that we see in the world today. The movie has been described as a textbook for how to start a radical terrorist organization, showing step by step how groups such as those form; preying on angered, disenfranchised civilians to join their ranks in order to spread chaos as a means of pushing forward a demented agenda. While the movie never intends to endorse this kind of behavior, it nevertheless shows a detailed look into the formation of a powerful political movement formed around a dangerous ideology. And some have argued that Fight Club glamorizes it as well. It’s hard to not notice that some of the tactics that the followers of Tyler Durden enact within the movie bear many resemblances to actions taken by fringe groups today. The mayhem of the Fight Club cult are in many ways akin to the pranks pulled by Internet trolls today, though many are much more malicious than anything that Tyler Durden came up with. There’s also the unfortunate way that elements of Fight Club has been co-oped into some hate groups’ talking points. You know the term “snowflake” that the Alt-right likes to use dismissively against their political rivals; that came from Fight Club. Fight Club certainly, as a movie, wanted to stir the pot a bit to shake conformities within society, but it’s unfortunate that the movie has in some ways emboldened some of the worst in our society, who have taken the absolute wrong message out of the movie as a whole.

The thing that gets gets ignored the most with regards to Fight Club as a narrative is that it is first and foremost a satire. In particular, it’s a scathing indictment on the societal definition of masculinity. One thing that gets forgotten about the movie is how the character of the Narrator is defined. The movie is about him trying to discover for himself what it means to be a man. First the story attacks how corporations define masculinity, as the Narrator spends his money on things that society says should define his worth as a man, but it all instead makes him feel empty. He only finds true happiness after he does the least masculine thing that society has defined; weeping openly in the arms of another man, or in this case the voluptuous “bitch tits” of his friend Robert ‘Bob’ Paulson (an unforgettable Meat Loaf). Later, he creates the persona of Tyler Durden through a need to have an ideal, masculine friend to rely upon, and that relationship in turn leads the Narrator down the road to promoting an ideology where the ideal of masculinity is defined by how hard you can hit the man that you consider your friend. This later evolves into the desire to destroy beautiful things, because they are a threat to a masculine ideal because they come from a decadent, corporatized place. This leads him to nearly killing pretty boy Angel Face (a young Jared Leto), because of that desire to destroy something he found beautiful, which gets to another deep psychological underpinning of the story. It should be noted, this movie called by many as a Fascist, testosterone fueled pro-male fantasy, was authored by a politically progressive, openly gay novelist who lives in the hipster capital of America; Portland, Oregon. This story was never intended to celebrate the ideal of the Heterosexual, Macho, hyper-masculine American male; it was meant to be a scathing indictment of that kind of person, and for some reason or another, that seems to have been ignored by both some of the movie’s fans as well as it’s critics.

Much like other misunderstood satires such as Blazing Saddles (1974) and Tropic Thunder (2008), the message seems to get lost in all the noise so that it appears to some that it’s participating in the very practice that it’s trying to mock. The way that I look at the movie Fight Club today is not as a step by step breakdown of how terrorist groups are formed like some have described it, but as an extremely effective dissection of the root causes of toxic masculinity. The brilliance of Chuck Palahniuk’s story is in the characterization of his Narrator. The fact that he is never named in the novel just illustrates the blank canvas that he is supposed to be in the narrative, and how that emptiness leads him down more dangerous roads in order to fill that empty void. Tyler Durden is a fiction made reality through the Narrator’s deranged desire to find a better version of himself, and as the story shows us, the desire to be more manly in a way drives one to become a little more monstrous each day. Palahniuk spotlights a very interesting point here, in how a pursuit towards a perceived ideal in masculinity sometimes drives men, even rational thinking men, into acting against their own self interest. This sometimes manifests in some ways towards actions like men taking unnecessary risks in order to prove their manhood (such as the car wreck test halfway through the movie), or threatening violence against those who threaten their masculinity. For the narrator, he’s on a dangerous journey of self-discovery, which ultimately leads him towards reconciling his perceived inadequacies with what he ultimately wants to be as a man; which is closer to being more compassionate. In order to get there, he literally has to destroy a part of himself in order to excise Tyler Durden completely from his mind; bringing the self-harm metaphor right to the forefront. You can see the same kind of toxic masculinity represented in those who same politically extreme groups that tout Fight Club as an inspiration, despite missing the whole point of the movie. How many men have unnecessarily harmed themselves trying to prove their masculine worth. How many of those men also attack other for not being masculine enough to their liking. The same hatred can be found in all those closeted males who take their frustration over their own sexuality and channel it into persecution of openly queer people as a result. Palahniuk, as a queer person himself, must have wanted to examine where that line of thinking might be coming from, and the narrative he found in the process did a brilliant job of helping to shed light on this issue in a meaningful way.

That’s why Fight Club feels just as relevant today, because we are currently in a climate where definitions of toxic and ideal masculinity are again beginning to stir heated debate. In my opinion, Fight Club subverts what you might expect of it. It presents this hyper-masculine pastiche on it’s surface, but underneath, it’s a biting satire of the destructive paths men take in order to reach an unrealistic ideal. It’s just too bad that much of it’s message has been lost over the last 20 years, and in some ways has been unfairly misinterpreted by both some toxic fans and also by ill-informed critics. It’s critique of toxic masculinity may be the most profound we have ever seen put on film. It’s a shame that in the same year, the Academy Awards celebrated a different kind of examination of masculinity with the very overrated American Beauty (1999). American Beauty also examines the psychological journey of a disgruntled American male, but instead of critiquing this kind of character, it almost lionizes his sudden transformation into a self-absorbed rebel, even making his lust over a teenage girl as a part of his awakening enlightenment. It doesn’t help that he’s also played by an equally toxic human being named Kevin Spacey. Suffice to say, American Beauty has aged terribly over the years and feels very much like a relic of it’s era, while Fight Club has become more relevant than ever. No other movie really digs this deep into the root causes of toxic masculinity and shows it reaching such dire extremes. What Fight Club shows is that much of the discord that arises from toxic masculinity comes from a dangerous sense of fear; fear of not being seen as manly enough by society and how that leads to destructive ends in order to compensate for those perceived weaknesses. Tyler Durden is not a poster boy for the best of masculinity; he is a villain bent on destructive ends. And the scary thing is, there’s a little Tyler Durden in every man, young or old, who feels like they are lacking something in their life. Fight Club, even with the veneer of it’s revolutionary punk aesthetic, ultimately wants us the viewer to choose compassion over destruction, and that is why it continues to remain a beloved classic to this day. Even 20 years later, I am still confident in my choice to have it top my list for the year 1999. And by examining how it’s message resonates today, I am not just confident it’s the best movie of 1999, I think it stands as one of my favorite movies, period. I am James’ complete lack of surprise.