When you look at the films that people would describe as being the quintessential 80’s movie, one of the titles that is likely to come up the most is the movie Tron (1982). Tron may not have intentionally been made to become a trend-setter of the era, but it certainly would emerge as such. The reason why Tron became one of the films to define the 80’s, particularly when it comes to aesthetics, was because it was perfectly placed at the forefront of the technological revolution that would define the decade after it’s release; the rise of computers and video games. Released in 1982, Tron would have an almost prophetic effect on the age of computers, as only a couple years later Apple Computers would release the Macintosh home computer, which would change the industry forever, placing what used to be a tool exclusive to high tech corporations into the homes of everyday citizens. In addition, the video game industry was blossoming into it’s own, with Atari leading the way in bringing video games out of the arcades and into the living room. Of course, the power of computing was still far more in it’s infancy than what we have today, but the beginning of the revolution to place computers and networking into every aspect of society was beginning to form in these crucial years. Tron stands out as a special film in that regard, because it gave us a glimpse of the way that computers would begin to take command of our lives, for both good and bad, and it did so while being a technological marvel in it’s own right. The story of Tron and how it came to be made is an interesting story in it’s own right, as is the legacy that it has left behind 40 years later. When you look at the circumstances that led to Tron becoming a reality, you can see how commitment to vision and a great bit of luck resulted in a movie that is unlike anything else that has ever graced the silver screen.

Going all the way back to the beginning, the origin of Tron came from an inspired Boston based animator named Steven Lisberger. Lisberger’s studio had been making a name for itself in the Boston area with award winning commercials. They were especially prolific in a style called back-lit animation, which was a popular design of the Disco era. Basically, they take their black line drawings on white paper, take the negative of that image and turn it into an animation cels which they call Kodaliths, with a mostly black background and clear lines defining the drawing. Then they would photograph that with the image back-lit with the light shining directly into the camera. From there, the line drawings glow against the black, and these can be shaded with any color the artist chooses, which creates a striking neon look to the image. To show off this technique, the Lisberger Studio created a demo reel with an back-lit animated robot throwing discs into the air. And because he was “electronic”, they called this animated robot Tron for short. The Tron demo was passed along to many different studios, as Steven Lisberger was hoping to have it be a selling point for his studio’s first ever feature. In the meantime, they managed to secure a special assignment from NBC, who were gearing up to broadcast the 1980 Olympics. The Lisberger team was commissioned to animate a pair of half-hour specials with Olympic sports played by animals, which would air alongside the real broadcast. The studio did deliver their projects, traditionally animated with one or two back-lit sequences, and they were well received by the execs at NBC. Unfortunately, though the first special did make it to air during the Winter Games at Lake Placid, the United States ended up boycotting the Summer Games that year which were held in Moscow. Thus, the second special never made it to air, which was disheartening for the Lisberger Studio. They did eventually get to release a feature length compilation of both parts on home video, but Animalympics (1980) was unfortunately not the big break that Lisberger and his team were hoping for. However, only a short while after this disappointing turn, they finally managed to get an interested party for their Tron project; and it was one that they probably never expected would look their way.

Enter The Walt Disney Company. Disney had been in a rough patch during the 1970’s. These were the post-Walt Disney years where the company was aimlessly trying to find it’s footing again after the sudden loss of their founder and guiding force. The movie output of the 1970’s was pretty weak, with the studio relying mostly on glories of the past with re-releases and low budget sequels. When the company came under the new management of CEO Ron Miller, Walt Disney’s son-in-law, there was a renewed focus in wanting to move the company out of it’s family entertainment shell and taking on more risks. In 1979, the Disney Company released it’s first ever PG-rated film called The Black Hole. Unfortunately for them, the slow moving Sci-Fi thriller couldn’t compete in a world where Star Wars (1977) now existed. Still, Miller and the other Disney executives wanted to try to make another more mature action flick that could help to define them as a movie studio. At this point, they came across the Lisberger Studio’s Tron demo, and they were impressed with what they saw. Initially, Lisberger wanted to make his Tron movie into a mostly animated film with live action bookends. But, the idea developed where they believed they could apply their Kodalith technique to live action film frames, and create the same back-lit effect with live action photography. They created samples of how that would look in practice, which turned out better than anyone had hoped, and they sent that over to Disney as a proof of concept. Disney was impressed with the look and they greenlit the film with a $10-12 million budget; a pretty favorable sum for a production team working on their first feature. So, work began on the Disney Studio Lot in Burbank for what would end up being a very unconventional movie.

Steven Lisberger had the vision he wanted to make a reality, but what kind of story would be at the center of his film. Around that time the video game craze began to explode, and within it, Lisberger was witnessing the rise of a very different kind of tycoon in the industry of computers. Instead of the tailor-suited corporate leaders in the high offices that were at the heart of companies like IBM and AT&T, there were the renegade pioneers of the tech world like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, presenting a different kind of visionary in the world of computing. This new stock of computing wizards was becoming even more evident in the gaming world, as these t-shirt and jeans wearing nerds were suddenly rising up in the tech world. Lisberger was fascinated with this clash of old vs. new in the world of computing, and found the centerpiece of what would be the conflict of his story. At the same time, he imagined what it would be like if one of the creators of this digital world actually ended up becoming a part of his creation, leading to an Alice in Wonderland journey into another world existing entirely within a computer. Through that, Lisberger created the character of Kevin Flynn, a computer genius outcast from the company that he helped to build. The mega corporation ENCOM now is run by the cutthroat Executive VP Ed Dillinger, who got where he is by stealing Flynn’s ideas. Through circumstances, Flynn ends up finding himself injected into the game system that he created, where computer programs exist as humanoid extensions of their creators, including one of Flynn’s own adversary Dillinger, found in the game world as a ruthless authoritarian named Sark. While Steven Lisberger’s story has all the tried and true elements of familiar adventure stories, he nevertheless stumbled across the forward thinking idea of how the cutthroat nature of the gaming and computer networking industry would go on to affect the lives of everyone in the near future.

The movie was an unconventional one to be sure. To bring his characters to life, it required actors with a strong imagination, as it required them to work with the minimalist of sets. Essentially the actors had to work on sets with completely black backdrops and wear skin tight black and white costumes in order to make the bac-lit effect work. Luckily, Lisberger managed to find a cast that perfectly fit within his vision and helped to bring a strong sense of sincerity to this unconventional project. In the role of Flynn, the movie cast rising star Jeff Bridges, who really took to the free-spirited nature of the character. For his counterpart in Dillinger, the movie gained noteworthy British character actor David Warner, who likewise excelled in the part of Sark within the gaming world. For the titular role of Tron himself, the stoic good cop of this crazy adventure, the movie found Western actor Bruce Boxleitner as their central hero, who brought a quiet reserve that fit well with the character, very much in the mold of a Jimmy Stewart or Henry Fonda for the film. With his actors in place, Steven Lisberger needed them to hopefully buy into the final vision that he was hoping to achieve. For them, they would be working in a very Brechtian kind of mode of staging, with nothing but themselves to act against. Today, it’s not far off from the way big budget movies use massive blue screens to fill out the world, but this was unusual in the early 80’s, when computer technology had not advanced to the point where you could see everything rendered in real time. For Lisberger and his team, they had to hope it would all match up in the end.

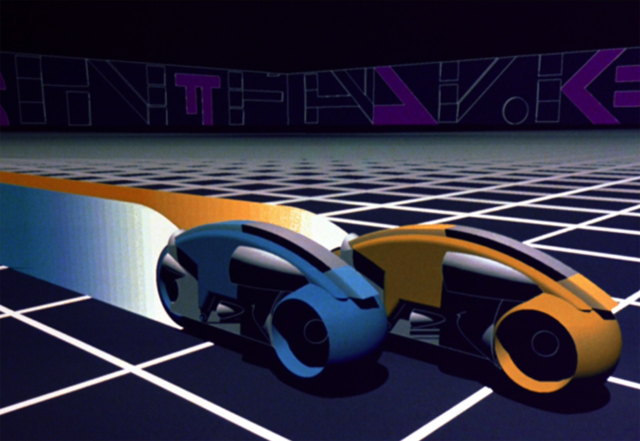

Though the back-lit visuals themselves would be unique enough to set the movie apart, it was another tool that would define Tron’s legacy even more. Tron would incorporate the first ever use of computer generated environments ever in a studio made film. Computer animation had been used briefly in films before; the wire frame Death Star blueprint in Star Wars for example, but they were as primitive and bare bones as you could get. Tron would be a great leap forward for computer animation, because it allowed computer graphics engineers the ability to not only build fully modelled environments and objects, but to also allow the simulated camera to boundless fly around these creations in ways never before seen on screen before. Though the computer animated creations of Tron are still simplistic in shape, due to the limitations of the technology at the time, it was nevertheless groundbreaking, and the digital world took notice. The animation was undertaken by a number of small CGI studios, and they were basically building all their tools from scratch; tools that in turn would go on to be the backbone of the industry for years to come. For many reasons, these are the things that we remember the most from the movie. The light cycle sequence in particular is one of the most iconic computer animated sequences ever made, and was probably the thing that inspired the advancement in the years ahead. The movie also introduced the first instance of character animation in CGI, with the personification of the villainous Master Control Program. Though simple in design as they are, the movie does an excellent job of making the primitive CGI effects feel palatable and authentic, which is crucial to making them work in conjunction with the live action elements of the film. Many in the industry took notice and saw the potential for how computer animation could be used as a cinematic tool. Pixar co-founder John Lasseter, who at the time was a junior animator at Disney, once said that “without Tron, there would be no Toy Story.” Computer animation almost assuredly would have found it’s way to Hollywood, but had Tron not made the bold first step that it did, we may not have seen the artform advance as quickly as it did.

Certainly Tron was going to be a bold statement from the Walt Disney Company, one that they hoped would help launch them into a new prosperous era. Unfortunately, short-sighted distribution execs wanted to move the movie off of it’s originally planned Winter 1982 release, and instead rush it into the more competitive Summer season. And this sadly happened to be one of the most competitive and noteworthy Summer seasons in movie history, with movies like Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982) and Blade Runner (1982) to contend with, not to mention the juggernaut that was E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (1982). It’s funny that Steven Spielberg managed to rule that Summer season with the warm and cuddly family movie, something that in the past used to be Disney’s foray, which they sadly did not have that year. Suffice to say, Tron did not perform as well as Disney was hoping it would. In fact, it may have been the final nail in the coffin for the Ron Miller era, as Michael Eisner was brought in by the Disney board soon after to re-steer the company in a new direction. Still, the movie was well received by those who saw it. Film critic Roger Ebert championed the movie for many years, calling it one of the greatest Science Fiction movies he’d ever seen. Over the years, the film developed a cult following, which grew larger over time, particularly as computer animation became more and more prevalent as the years progressed. It even developed a presence within the pop culture as one of the granddaddies of a new style of storytelling and artwork known as “Cyberpunk,” alongside it’s fellow 1982 competitor Blade Runner. You can definitely see the DNA of Tron in many cyber based thrillers after, like The Lawnmower Man (1992), Johnny Mnemonic (1995), and it’s more successful cousin The Matrix (1999). Over time, the cult following for Tron grew strong enough for Disney that it convinced them to make a long awaited sequel. Though Steven Lisberger had ideas for a sequel, Disney instead went in a different direction, though Lisberger stayed involved as a producer. The sequel, Tron Legacy (2010), managed to bring back Jeff Bridges and Bruce Boxleitner to their iconic roles, but it also built upon the world that we had seen before, realizing it on a grander scale with the technological advances that have come as a result of the original movie’s legacy in computer animation. Though the movie was well received by audiences, it again didn’t perform as well as Disney had hoped, though it did much better than the original by comparison. Hopes of a franchise were dashed again, but the legacy still remains strong.

It’s interesting looking back on a movie like Tron and seeing how the age of computers was viewed in it’s early infancy. Remarkably, what Steven Lisberger imagined about the direction of the technology in the computer age has been scarily prophetic over time. He foresaw a lot of the good and the bad that would come from a world where computer technology would take over so much of our daily lives. With the personification of the Master Control Program (MCP) as this authoritarian dictator run amok, he imagined the dangerous implications of what it would be like if computers took on too much control. It wouldn’t surprise me if James Cameron had the MCP in mind when he created his own evil AI overlord SkyNet in his Terminator movies. Even in our own real world today, the algorithms that run so much of the media that we consume bear a bit of resemblance to the kind of control that the MCP in Tron abuses. Even in the characters in the movie, you can see the clash of egos that bear a lot of comparisons to the tech CEO’s of today. We see a lot of Kevin Flynns and Ed Dillengers today, with the Jeff Bezzos and Elon Musks of the world, all vying for more control in a world becoming more and more digital. Even still, Tron does offer positive outlooks on the uses of computer technology within it’s story. It foresaw video games as a burgeoning artform, which at the time of the movie’s making hadn’t advanced past Pac-Man and Donkey Kong. In the movie, you see Kevin Flynn playing an arcade game with fully rendered 3D environment. Such technology wouldn’t be possible for another 15 years or so, but Lisberger believed it was possible enough to include a game with those kinds of graphics in his movie, and today it looks like a primitive version of the first person shooters that dominate the industry today. It was a movie well ahead of it’s time, and though audiences weren’t quite ready for it back in 1982, it has since become one of the founding stones of the computer based culture that we live in today. Imagine how different computer animation would be today had Tron not taken that first step when it did. Steven Lisberger and Disney certainly made a mark that continues to ripple through the industry today. And even though it’s outdated in many ways, it still remarkably holds up even with all the advancements that have been made over time. There really is no other movie like Tron, not even it’s sequel which is a very different kind of movie. It is a true original and an engaging adventure that continues to have it’s influence shown in both users and programs alike these four decades later.