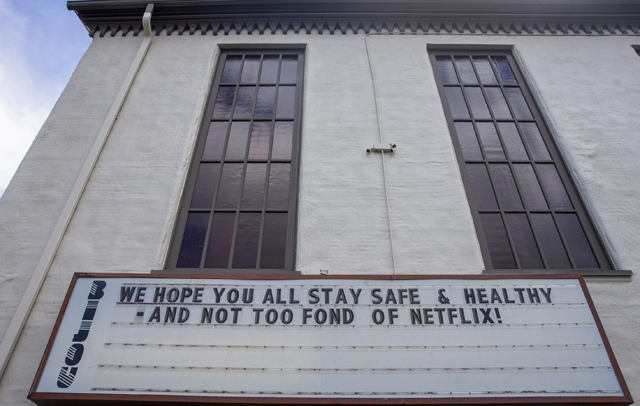

It’s Christmas Day. We’ve all had a pretty hectic year, but if you are making it to this festive time with your mind set in the right place, then you’ll no doubt be feeling the warmth that the season brings. We all celebrate the holidays in our own way, depending on our background, cultural upbringing, and station in life, but there is no doubt a lot that many of us still have in common when we reach the Holiday season. No matter what holiday it is that we celebrate, this end of the year season is about coming together and expressing how much we are grateful for having the loved ones in our life to share these moments. That and giving each other lots of presents. That in itself can be both something wonderful this time of year, as well as a headache. We also have that in common, scrambling through all the days and weeks trying to prepare for the big day. Whether we are decorating, shopping, or preparing the big Holiday meal, many of us are putting in a lot of work to make the season bright. And all for a brief moment on Christmas morning where we open our gifts together. It’s a time of joy, but also frustration. But even these hectic moments have come to define the season itself, and in many ways, the perseverance to make the the holidays perfect become memorable moments themselves. In some ways, they turn into war stories that we tell each other, sort of a way of bragging to show just how much Christmas spirit we have. I have some of those two, with my years spent working in retail during the holiday season. This goes for the shopping experiences as well as all the headaches at home with making everyone happy during the holidays. Oftentimes, there are just as many tears to be had over the holiday season as smiles. We all recognize the trials of a holiday season because many of us have gone through it ourselves. No Christmas is 100% perfect, and the ones that we remember as being perfect may be just rose colored glasses over a foggy memory. But, that strive for perfection is a universal feeling, and the best we can do is to laugh it off in the end and just enjoy the holiday mood. Though many movies show the ideal types of Christmases we’d like to have, there is one movie that perfectly encapsulates all the things that could go wrong during the holidays: National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation (1989).

Christmas Vacation is an all time classic holiday film, but one that I think goes against the grain of what a typical Christmas movie should be. It’s a movie about everything going wrong during Christmas time, despite the best efforts of it’s central family, The Griswolds, to make everything perfect. And by the Griswold’s, I mean the father, Clark Griswold (Chevy Chase) who takes holiday festivities to a cult like obsession. And every mishap that befalls Clark and his family is played up for laughs. The movie overall is a farce in the very classic sense of the word. There really is no driving plot to speak of, other than a couple of loose threads like Clark’s ambition for a perfect holiday and his anticipation for a Christmas bonus check from his greedy boss. It’s merely just a collection of moments with hilarious punchlines at the end of each scene. We see the family going pick out their Christmas tree, Clark decorating the house, the extended family members making their arrivals, and the family sitting down for a Christmas Eve dinner. Things we all have our own experiences with during the holidays. But, as the movie unfolds, every possible thing that could go wrong does. The tree is too big, and Clark forgot to bring an axe; Clark nearly falls of the roof many times while putting up the lights; the grandparents all hate each other; and the Christmas Turkey is cooked too dry to be edible. All these mishaps are filmed with the same kind of manic zaniness of a Marx Brothers or Charlie Chaplin comedy, which is typical of the National Lampoon brand. And yet, there is still an underlying truth beneath all the farce. None of the scenarios that Clark Griswold finds himself in are too far fetched; we all can identify with all the mishaps that befalls him, because many of them have often happened to us too, though maybe not to the same extreme extant. It’s that combination of relatable mayhem and the unrelenting farcical tone of the movie that really helps to keep the film a perennial favorite.

It might surprise many that National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation is the third in a series of comedies, because it stands pretty well on it’s own as a stand alone movie. The series began with the celebrated National Lampoon’s Vacation (1983). Written by John Hughes and directed by Harold Ramis, Vacation followed the Griswold family through a similar series of unfortunate events, only it’s during a Summer vacation trip that takes them to a fictional theme park named Walley World. That film likewise is renowned for it’s manic farcical tone and often mean-spirited humor. It also marked Chevy Chase’s first post Saturday Night Live hit as a headlining star. And it was a role that he played to a “T”; a highly strung out dad trying his best to make everything perfect even though nothing goes right, and it only makes him sink deeper into his own mania. Where I think a lot of people forget that Christmas Vacation is the third film in the series is because of the often forgotten sequel, National Lampoon’s European Vacation (1985). Made right on the heels of the original, and retaining John Hughes as screenwriter, the sequel obviously did not have the same magic of the original film. Something just felt off taking the Griswolds abroad and placing them in Europe rather than the American Midwest. And I think that’s where the problem lies with European Vacation; it’s just trying to be the first movie all over again, and it can’t catch lightning in a bottle twice. The change of scenery doesn’t hide the fact that it’s all the same farcical situations all over again, and all it does is spotlight the flaws all that much more. So, when the opportunity came to make a third film, Hughes and company decided to do something different, which ultimately helped to bring fresh new life into the series; they brought the Griswolds home for the holidays.

The at home Christmas seemed like a natural progression for the series to take, but it also opened up the series to a fresh set of mishaps that could befall Clark and the family. In essence the dynamics are still the same. Clark is the driven to perfection man that we are all familiar with from the last two films, and his mania is perfectly countered off of his long suffering wife Ellen (played again perfectly by Beverly D’Angelo). What is especially funny is that the movie keeps the tradition going of recasting the Griswold children in every new film. This time around Rusty and Audrey Griswold are played by a very young Johnny Galecki and Juliette Lewis respectively, and of course the recasting is never brought up at all. The same progression of cascading problems also happens to the Griswolds, but here it’s all set at home. The gimmick of them driving across the country is out of the story, and that allowed John Hughes to craft his comedy around the characters’ home life. And that offers a whole different set of comical situations to mine from. This is especially hilarious to see with Clark’s manic personality coming through. He not only decorates the house, he decorates to a point where he uses so many lights that it literally drains all the power from the community. The tree he picks out is so big that it destroys half the living room once it’s branches are unbound. Everything is not a minor thing with him; he has to take it to the nth degree. It’s all over the top, but John Hughes grounds it in a very real place. Every situation feels like something that naturally would happen, and probably comes from real place. John Hughes was a midwestern kid from Michigan who probably experienced his fair share of crazy Christmases. Whether he wrote himself into the character of Clark, or based him on members of his own family, you really get a sense of Hughes finding a universal story within the mishaps of the Griswolds and their striving for not just a perfect Christmas, but also a sane one.

What is interesting about the movie is how Clark Griswold comes across to us the audience. We are meant to sympathize with his ordeals, but it’s often hard when Clark is not the best person in the world. Carrying over some of the character traits from the previous films, we see Clark as a very flawed man. He insults his co-workers, constantly puts his family in harms way in order to achieve his often impossible goals, and at one point even flirts with a girl at a department store while his wife is somewhere else. Clark, in many ways is a self-obsessed jerk underneath that suburban dad exterior. But, that’s one of the most fascinating aspects of Clark as a character. As flawed as he is, he is very much an everyman whose problems are all too recognizable. It’s through his striving for a perfect Christmas that we see his attempt to be a better man, and it makes all the funnier when he fails horribly at it. I think if he was a purer soul, the farcical situations he would find himself in wouldn’t feel as funny as they do. Because he is sometimes a jerk to others, it makes it funnier when we see misfortune fall his way. But, it’s not to the point where he is too unlikable or the misfortune too stacked against him. The movie is all about that balance between hilarious hubris and triumphant comical resolution. It helps that the Griswolds live next door to an uptight Yuppie couple, played by Nicholas Guest and a pre-Seinfeld Julia Louis-Dreyfus. Clark’s mean-spirited self-obsession feels much more earned and celebrated when the misfortune falls the neighbors’ way. He may not be the antithesis of a George Bailey, but Clark Griswold is a Christmas character worth celebrating this time of year, because he honestly is the one who represents how we all feel during the holidays.

There is one moment in particular in the movie where I think the movie reveals exactly what drives Clark Griswold, and in many ways shows us what we see of ourselves in him. At one point, Clark goes up into the attic to hide Christmas presents from the rest of the family. However, his mother-in-law ends up closing the roof access door, not knowing that he is still up there. Now, Clark is stuck in the cold attic in his pajamas, with no way out. While going through some old boxes to find extra layers of clothing he can put on in order to not freeze, he finds some old 8mm film reels. Not knowing how long he’ll stay up in the attic, he finds the family projector and begins to run these old films strips through it, using a white shirt as the screen. On the film, we see Clark as a young boy celebrating Christmas with his family. It’s in this scene where it finally dawns on the audience what is driving Clark Griswold to making this a perfect Christmas for his family; Nostalgia. While watching the movie projected in front of him, we see Clark at his most content, even shedding a tear while he has a beaming smile on his face. Though the film is grainy, worn out, and not ideally projected, it brings Clark back home to the days when Christmas was ideal for him. Naturally, we all look back on the Christmases of our youth with fond remembrance, but that’s because the burden of the holidays were not on our shoulders yet. As kids, we were the main recipients of holiday cheer. We didn’t have to spend hours at the mall looking for the right presents, or work for days to put up the decorations in the cold of winter. The holidays change for us as we get older, and many of us can easily adapt to the new dynamic. But, Clark is still trying to hold onto when Christmas was just as self-fulfilling as it was when he was a child. It’s really interesting that the movie takes a pause from the farcical situations from before and gives us this moment of reflection that tells us more about Clark than we’ve ever known before. Of course, the movie punctuates it with Clark falling through the ceiling access door once Ellen reopens it, bringing us right back to the comedy. Still, it’s a moment in the movie that probably captures the holiday spirit the most, as it personalizes what Christmas means for Clark Griswold, and that it’s a whole lot more than just the superficial traditions; it’s a quest to feel inspired by the holidays again.

It’s really interesting to see where Christmas Vacation falls within the John Hughes filmography. He was only the screenwriter on this one, with Jeremiah Chechik capably handling the direction, but it really shows a certain mode that he was finding himself in as a story-teller. This movie came in between two other Christmas themed comedies that Hughes also wrote, 1989’s Uncle Buck and 1990’s Home Alone. They are all very different films that use the Christmas aesthetic, and yet all three perfectly illustrate the way that John Hughes mined American holiday traditions for comedic effect; including Thanksgiving as well with Planes, Trains, and Automobiles (1987). Christmas Vacation clearly is the movie that mines the foibles of the holidays the most, but there is a characteristic sense of comedic precision found throughout all of them. Hughes liked to turn the holidays on it’s head and slyly insert the kind of slapsticky, mean-spiritedness of the comedies he grew up with into this thing that is supposed to be so pure. At the same time, there is a genuine love he displays for the spirit of Christmas in his movies, and I’m struck by how much of Hughes own creative trademarks have themselves becomes part of our own holiday nostalgia. I think that his series of holiday themed movies were instrumental in helping to create the Christmas playlist of holiday standards that we hear every year on soft rock radio stations. That’s true for Christmas Vacation as well, which has something as enriching as Ray Charles “The Spirit of Christmas” to something as bouncy as Bing Crosby’s “Mele Kalikimaka.” In many ways, John Hughes contributed more to the nostalgia for the holidays that we continue to have thanks to his choices of needle drops. There’s a cynical edge in the movie, but one that never belittles the idea of the holidays itself. Like all great comedies, it asks us to find the humor in the things we hold sacred and in that sense, John Hughes achieved what he wanted; to create a farce in the same comedic spirit of those that came before him, like Chaplin, the Marx Brothers, and even the likes of Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner. And it’s definitely a flavor of comedy that the holiday season definitely needs.

There are countless moments in Christmas Vacation that stand among the funniest ever put on film. The climatic Christmas Eve series of events are especially hilarious, in just how much it cascades into pure chaos. From a cat that’s fried to death by faulty Christmas light wiring, to Clark’s elderly aunt (played by original Betty Boop actress Mae Questel) mistaking the Pledge of Allegiance for a prayer, to Clark’s Cousin Eddie (a perfectly demented Randy Quaid) kidnapping his boss after Clark did not receive his Christmas bonus in the mail. It’s just the right balance of mayhem and genuine Christmas spirt that I want to see in a movie like this. It’s both naughty and nice, cynical but uplifting. Naturally myself and many like me return to this movie every year and enjoy it over and over again. For some, the holidays don’t feel complete without it playing at least once. It’s not an unexpected holiday classic; how could it be when the holidays are ingrained into every frame of the movie. But, it’s one that’s not afraid to buck a few traditions and reveal some of the misfortunes of the holidays in a hilarious manner. Perhaps the highlight of the movie is it’s most profane moment, when Clark reaches his breaking point and delivers his manic, single breath, vitriolic rant against his cheapskate boss who cut his holiday bonus out of his yearly salary. That’s something you won’t find in a wholesome Christmas movie. At the same time, the movie celebrates the idea of trying to make the holidays better for others. Clark Griswold may be a maniacal sociopath, but his heart is in the right place when it comes to making the holidays work out for his family. It’s just that the problems fall out of his control and build towards a chaotic end. Even still, he pushes ahead and declares, “We are going to have the hap, hap, happiest Christmas since Bing Crosby tap danced with Danny f***ing Kaye.” The Griswold family Christmas is course, crude, and chaotic, but it’s not unlike the kinds of Christmases we have had ourselves. The only thing is that we shouldn’t let the drive for perfection cloud our own enjoyment of the holidays. Even as everything has cascaded into insanity by the end, Clark Griswold finds that special sense ultimately too, and that helps to make Christmas Vacation in the end feel like a hopeful tribute to the holidays. So, to all of you, Merry Christmas and thank you for reading. Now where’s the Tylenol.