There are a variety of flavors when it comes to holiday themed movies to choose from to watch this time of year. There are your wholesome traditional religious themed classics, your subversive comedic classics, countless animated classics, as well as the warm hearted romantic classics, all of which will be filling your airways over the course of the weeks leading up to Christmas Day. But, in some cases, there are Christmas movies that cross over into the less wholesome entertainment and add a bit of spice to the holiday cheer. Specifically, these are movies that use the holiday aesthetic, but add a bit of horror and action to the mix. This is why the debate over Die Hard (1988) being a Christmas movie is such a passionately argued one this time of year. Not every movie about Christmas needs to be for all ages, and Die Hard is certainly the movie that proves that point. But, at the same time, Die Hard isn’t inherently about Christmas either; it’s just a story that takes place during the holiday season. Remove the holiday overlay, and Die Hard would be hardly different. But, even still, many fans choose to make Die Hard part of their holiday watch list every year, and it’s without question a great movie to watch regardless of the time of year. The interesting thing is that Die Hard has become such an influential film over the years that it has inspired filmmakers to resolve the Die Hard Christmas question by actually taking the same premise and fully making it about the holiday. And that is accomplished by swapping out John McClane for Ol’ Saint Nick. It’s such a no-brainer idea for a Christmas themed action movie to make Santa Claus an action hero, so it’s surprising that more movies haven’t attempted it over the years. There have been two noteworthy attempts in recent years that work with this premise to varying degress of success. And comparing them together, we see what it takes to make Santa Claus an action hero worth rooting for.

During the pandemic year of 2020, a low budget action movie centered on Santa Claus became available for video on demand just in time for Christmas. Fatman (2020) features Mel Gibson as a world weary version of Santa, less motivated by holiday cheer and more about keeping his operation afloat in a changing economy. His Santa is more factory foreman than a jolly old elf. While he devises a plan to save his North Pole operation from foreclosure by agreeing to a military contract with the U.S. Government, a spoiled rich kid named Billy (Chance Hurtsfield) hires a hitman (Walton Goggins) to assassinate Santa after being slieghted on Christmas for being naughty. The hitman has had a longtime vendetta set on Santa, and he goes to the North Pole with deadly force. What results is a deadly attack on Santa’s compound with plenty of military and elf blood spilling on the new fallen snow. The movie garnered a bit of attention over the lockdown affected holidays, especially given the silly premise and the casting of Mr. Gibson as Santa. A couple years later, another action movie centered on Santa was released, only this time it’s one that unmistakably leans more into the Die Hard formula. Violent Night (2022) involves Santa (played by David Harbour) finding himself embroiled in a home invasion scheme by heavily armed burglars. Like with Det. McClane in Die Hard, the burglars are unaware of Santa’s presence until he begins to use his ancient Viking warrior skills to pick them off one by one. He also becomes aware of the situation by being in contact with one of the hostages; a young girl named Trudy (Leah Brady) who communicates with him via a toy walkie talkie. And of course all of the mayhem ensues in bloody excess, fitting the title of Violent Night. Despite taking on the same premise, Santa Claus being an action hero, both films are thankfully very different in narrative, and actually do interesting things with the character of Santa in general that isn’t too out of character for the Christmas icon that we know. The only thing is, which film did a better job of achieving that goal.

“Damn chickenshit reindeer left me here to die.”

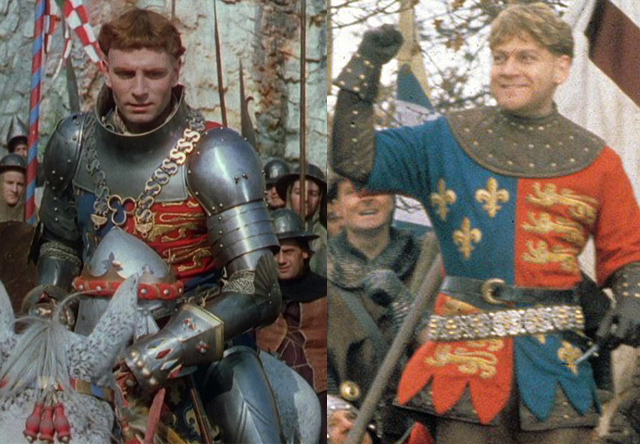

Probably the most important thing to compare between each film is how well they portray the character of Santa himself. Santa Claus has been portrayed many different ways over the years, but in these two cases, Santa has to be believable as the central character of an action movie. Both Mel Gibson and David Harbour are no strangers to working in action oriented filmmaking, but it is interesting to see how differently they approach their combat scenes in their respective movies. Mel Gibson’s Santa is much more grounded and serious. Despite the absurdity of the premise, Gibson plays the role very straight-forward, making his Santa grizzled old man whose doggedly protective of his territory. Think of the Santa in Fatman as a Christmas version of a doomsday prepper, ready to take up arms if he finds his home base threatened by outsiders. Basically, Mel is playing Santa not unlike his own grizzled, society shunning self, just minus the closed-minded bigotry. In a sense, this fits the movie he’s in, given that the action scenes are brutal and not played for laughs. Fatman surprisingly plays the action straightforward, with the violence at times being fairly brutal. Violent Night by contrast is unmistakably an action comedy, with the violence played up to far more absurd levels. And David Harbour matches that tone perfectly. His Santa is not the most skilled action hero; part of the time he clumsily gets himself bruised up before he’s able to get his own licks in. A lot of the movies best laughs come from the fact that Harbour is able to sell the sloppiness of Santa’s response to the situation just as well as he does with Santa fighting at his most competent. And in general, his Santa is just a far more endearing character in that aspect. The biggest problem with Mel’s Santa depiction is that he never elevates the persona beyond just that gruff center of his performance. He does get a few great tough guy moments, but they are few and far between. Harbour is consistently entertaining as Santa, from beginning to end; from his boozy, lackadaisical introduction to his bad ass final battle, his Santa Claus finds that perfect balance between fierce and funny, which helps to make his film much more fun in general.

“Some kids with a deer rifle put two holes in the sleigh and one in me. All I have is a loathing for a world that’s forgotten me.”

There is also a major distinction in the films with regards to the threats that Santa faces. In this regard, Fatman is the one that does a better job of breaking the mold. Violent Night has a fun batch of baddies, led by John Leguizamo’s increasingly frustrated ringleader. At the same time, the movie perhaps borrows a bit too much from it’s Die Hard inspiration, as most of the henchmen are little more than archetypes, with Leguizamo’s Scrooge being not much more than a discount Hans Gruber. Fatman on the other hand has a fantastic villain in the form of Walton Goggin’s Skinny Man. Skinny Man is a refreshingly different spin on the kind of hired hit man character that you would see in a action film of this type. He takes the job of killing Santa Claus not just because of the money, but because he has devoted his life towards hunting Santa Claus down out of vengeance, making him the most qualified for the job. We learn that he was slighted out of receiving a present as a kid because he was on the naughty list, and this was the tragic event that sparked his vengeful spirit. Absurd, yes, but the great thing is that Walton Goggins plays the character completely straight. He understood the assignment and he turns the Skinny Man into a legit intimidating presence in the movie. What also makes the character work within the movie is that his deadly serious take on the character is balanced off of that of the kid playing the spoiled rich Billy; who seems to be a thinly veiled parody of Donald Trump, with the loose fitting suits, childish temperament, and malignant narcissism. The kid definitely plays more into the absurd side of the premise, which helps to give Goggins the leeway to play more into the darker aspects of the character. And between both this and Violent Night, the Skinny Man is without a doubt the most interesting character to have been imagined through this kind of premise.

One other thing that works in Fatman’s favor is that it is far more interested in worldbuilding around it’s premise than Violent Night. Violent Night runs primarily on the belief that most of the audience will already be aware of the mythology surrounding Santa Claus. All of the Santa related stuff is more or less there to satisfy the punchline of Santa being out of his element in this Die Hard scenario. The movie does add the interesting aspect that Santa started out as a mercenary Viking with a high kill count in his past, and his weapon of choice was a sledgehammer named Skullcrusher. But, apart from that, the movie sticks fairly closely to the Die Hard scenario and doesn’t build on any lore from there. In Fatman, the movie goes much more into conforming the mythology of Santa Claus into a grounded, real world setting. Instead of being at the geographic North Pole, Santa’s base of operations is actually in a rural Alaskan town called North Peak. On the outside it looks like any other farm, but underground is where you’ll find the cavernous workshop, which looks not unlike most Amazon distribution centers. It gives the Santa mythos a very 21st century aspect, but even still, the movie includes some of the fanciful elements. His workshop is still run by elves and his sleigh is still led by flying reindeer. The modern trappings of the workshop does a decent job of reinforcing Santa’s disillusionment with the work that he does, as he grows more weary with the increasing corporatization of the holiday season. While I have a feeling some of the grounded look of the film was due to the movie having a very miniscule budget, I do give the movie credit for working around that and making it an integral part of the worldbuilding of it’s story. It certainly makes it a different version of Santa’s workshop that we haven’t seen on film before, and it also makes for the right kind of setting for the violent confrontation that the movie ultimately leads to.

“Skullcrusher’s my hammer. My favorite hammer. I was a surgeon with that thing. Used to be able to take three heads. Line ’em up…”

There’s definitely one thing that the two movies have in common, which is that both genuinely earn that R-rating for violence. With Fatman, the movie remains fairly blood free until the very end, with only short bursts committed by the Skinny Man until he eventually makes his way to Santa’s compound. Then the blood spilling begins. Violent Night by contrast gets to the violent stuff pretty quickly, but it does a fine job of maintaining the escalating violence throughout and even manages to one-up itself the further it goes. Apart from the Die Hard influence, it’s clear that Violent Night was also inspired by another Christmas classic; Home Alone (1990). Santa Claus not only fights off the bad guys in Violent Night with his bare hands, but also with whatever Christmas themed decorations he has on hand; much in the same way Kevin McCallister would’ve. Though of course Kevin never impaled one of the Wet Bandits in the eye with a Star tree topper before. There is a scene where the little girl Trudy even gets in on the action as she lures some of the bad guys into the attic, with traps that are pulled straight out of Home Alone, only taken to the fullest gory ends (and you guys thought the nail in the foot part was cringe inducing). The violence in Fatman is played much less for laughs as they are in Violent Night, with the film leading to a very intense shoot out at Santa’s compound. If you ever wanted to see a gun-touting Santa Claus duel it out in tactical combat, this is the movie. The degree to which the audience responds to each film depends on the level of violence that they are willing to accept. Violent Night is over the top and hilariously gory while Fatman is gritty and intense, and the two films pretty much deliver on what they promise.

But there’s one other question, which is whether one film works better as a Christmas movie than the other. In this regard, I feel that Fatman falls a bit short. It is more of a action movie wearing the skin of Christmas, while Violent Night brings in a lot more of the feel of the holiday season. I think this is largely due to the way the secondary plot works in addition to the one involving Santa. The family at the center of the home invasion function very well as an element of the Christmas style story being told, because they are a perfect distillation of a dysfunctional family trying way too hard to have a normal Christmas gathering. I’m sure that it’s no accident that Beverly D’Angelo was cast as the matriarch of this family, since she famously played Ellen Griswold in the classic National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation (1989), the ultimate dysfunctional Christmas comedy classic. The way that this family plays cutthroat with each other is just as hilarious as all of the Santa bits in the movie, and probably hits close to home for some people who have tried to soothe troubled waters over the holidays. At the same time, the family does come together through the ordeal, though they still maintain toxic elements of their personality, and helping out Santa Claus beat back the bad guys does give them a renewed belief in the holiday spirit. This helps to make Violent Night feel more like a seasonally appropriate movie. Apart from the mythic Santa Claus elements, there really isn’t much that makes Fatman feel like a holiday film. The movie could have just been about a lonely farmer fighting off an intruding assassin and the story would have been roughly the same. There’s no, shall we say, Christmas magic to it. Violent Night by contrast definitely wants to leave it’s audience with a sense of the holiday spirit by the end, even after seeing a man get violently ripped apart after being pulled up a chimney. That’s probably why it’s the film that likely will be re-watched more often as part of a Christmas watchlist.

“You messed up big time, fat man!”

One of the pleasing things about the attempt to officially work the Die Hard formula into an authentic Christmas story is that it feels so natural. It makes sense that it would fit, given that Die Hard was about disrupting a festive moment with a violent threat. Only seems fitting that Santa Claus would be the one to save the day in the end. As far as Fatman and Violent Night go with their takes on Santa Claus as an action icon, they both fit within the rules set by their respective films. Fatman is a grounded, gritty film, and Mel Gibson does fit that version of Santa pretty well. Violent Night on the other hand certainly plays things out in a sillier way, but to a point where it doesn’t do a disservice to the action, and David Harbour perfectly embodies that aspect of his Santa Claus. You can definitely look at Harbour’s Santa as being the more Bruce Willis like of the two, while Mel Gibson’s Santa is more Clint Eastwood. Out of both movies though, the best character still remains Walton Goggins Skinny Man, who is a genuinely effective and intimidating action villain. The two movies more or less succeed in what they set out to be, but I feel like I’m going to be revisiting Violent Night more often as a Christmas re-watch. It’s got a lot more wild moments that manage to make me laugh out loud, while Fatman just worked out as a serviceable action flick. Violent Night also is the one that seems to celebrate the season a bit more, while Fatman is a tad more cynical. But, what both movies do prove is that you can indeed turn Santa Claus into an action hero. It’s definitely a sign of the versatility of the character, where his persona is not tied to any traditional bounds. That’s why he can remain a relevant symbol to changing times and attitudes while still being distinctly Santa Claus. I certainly like seeing a Santa that can hold his own in a mano y mano fight as these two films managed to show. There’s a lot of stories that you can tell with Santa Claus, but in the end, he still has to represent that spirit of the season. As long as a movie can do that, it doesn’t matter if Santa is also packing heat or cracking a few heads as well. Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good fight.

“Ho, ho, holy shit.”