While film-making in general is a collaborative process, the role that takes the most prominence in the creation of a film is that of the director. It’s the director who makes sure that everything captured in the camera’s frame is precisely in tune with the storytelling. Primary among all their different tasks on the set is to guide the rest of the production team itself, ensuring that everything that the camera captures creates the perfect illusion of life. This includes working with the cinematographer to determine how the film will be shot, dictating to the production designers what is needed on the set to fill each shot with foreground and background details, and of course, helping the actors find the motivation they’ll need to perform as their character within each scene. It’s a multifaceted job that requires a lot of personal involvement, and that is why the director is often given the most important credit on a film. Authorship in film-making often falls to the director, because they are the chief creative force behind each project. In many cases, there are filmmakers whose style is so distinctive, that you can look at their whole body of work and see some chief characteristics that define it as a whole. That’s why I wanted to start a new series for this site dedicated to looking at the distinctive film-making styles and cinematic breakthroughs made by some of the most celebrated filmmakers. Entitled “The Director’s Chair,” my hope is to spotlight a different director in each entry of this series and spotlight 5 distinctive things about each one that has made them a special contributor to cinematic history, whether it be a distinctive trademark, a unique cinematic style, or just the impact that they have left on the industry as a whole. And for the premiere article in this series, I decided to not just look at only one director, but instead spotlight two filmmakers that somehow have established themselves under a singular visionary style: the Coen Brothers.

Joel and Ethan Coen have worked together continuously for the last 32 years, beginning with their debut film Blood Simple in 1984, all the way up to their most recent film, Hail, Caesar (2016), and they plan on continuing to collaborate for many years to come. They’re working relationship has been so close in fact, that they’ve often been jokingly referred to as “The Two-Headed Director.” And it’s easy to see why. While many other films that have been directed by two or more directors feel disjointed in their storytelling, every single Coen Brother movie is uniformly distinct and feels characteristically in line with every other movie they have made. Sure, their style has evolved over the years, moving from the straight-forward thrills of Blood Simple to the complex, psychological tension of No Country for Old Men (2007), but the Coen Brother’s filmography has become something quite unique in the world of film-making that is purely of their own design. One of the main reasons they have built such a unique body of work is mainly because of that close collaboration. They write, produce and direct all of their movies, as well as work solely on the editing, under the pseudonym of Roderick Jaynes. They also remain in charge of picking each of their projects; never taking on a commercial studio production and always working independently. It’s worked out for the most part, apart from a few misguided speed bumps (2003’s Intolerable Cruelty and 2004’s The Ladykillers). Their ability to experiment in different genres has also given their filmography a nice bit of variety, even though their style remains the same. And among their body of work, distinctive characteristics become apparent, and it’s those features that I want to elaborate upon in this article, and see how they define each of the different films that the Coen Brothers have made over the years.

1.

CHARACTERS

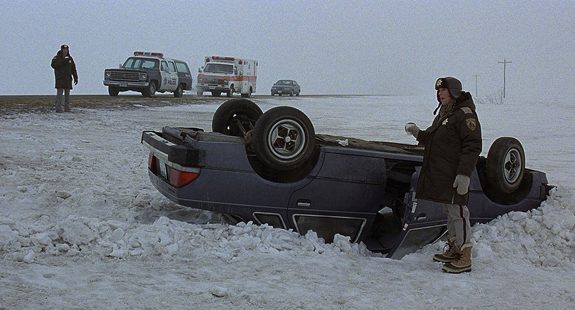

If there was ever something that truly defined a Coen Brothers movie, it would be the unforgettable characters that populate them. The Coens are masters of creating easily definable, enduring characters in their movies, and it’s mainly because their characters are perfect representations of every day human foibles personified in a single being. Whenever we watch a Coen film, we always end up remembering these characters. We don’t always remember their names, but we remember their personalities. There are some extreme personalities that exist within their strange universe, such as John Goodman’s Walter Sobchak in The Big Lebowski (1998), or Nicolas Cage’s H.I. McDunnough from Raising Arizona (1987), but the most endearing characters the Coen Brothers have ever created are the ones more grounded in reality. One of their most beloved creations would have to be Marge Gunderson from Fargo (1996), played by Joel Coen’s own real life spouse Frances McDormand. Marge, a pregnant small town cop in the American Midwest, is such a fascinating character in the movie simply by being so ordinary. Her charm is not in being quirky, but by being the audience’s eyes into the crazy world that she stumbles into, and the more identifiable she is, the more we relate to her. She’s just the average working class American hero, the kind of person who you’d want to meet in real life and listen to her stories, and that’s why we love her. Another interesting aspect of Coen Brother characters is their often helpless situation. The Coens had a religious upbringing in the Jewish faith, and while their movies aren’t based in religion, some biblical themes do manifest within their stories; in particular, the story of Job. Like the biblical character, many of their characters often have to deal with situations well out of their control. But while Job was shown mercy by God in the Bible, Coen Brother characters often left out to dry with no redemption or hope, like John Turturro’s Barton Fink or Michael Stuhlbarg’s Larry Gopnik in A Serious Man (2009), or Oscar Isaac’s Llewellyn Davis in Inside Llewellyn Davis (2013).

2.

PITCH BLACK COMEDY

Another trademark aspect of the Coen Brothers’ movies is their incredibly dark sense of humor. There are certainly some Coen Brother films that are more serious than others, but the one thing that defines them all is a twisted, often absurdist outlook on the world. Oftentimes this is played off of the different quirks of the characters interacting with one another, but other times it’s because of the completely insane situations that the characters find themselves in. Fargo is often cited as one of the perfect examples of a black comedy, and that’s due to the film’s horrific situation of kidnapping and murder being undercut by the silly personalities involved within it. Any other filmmaker would have played a story like Fargo straight, but the Coens found the interesting angle of exploring how this situation would play out within this type of Western Minnesota community. The backwaters setting and peculiar regional accent are certainly poked fun at within the movie (never in a mean spirited way though) and that helps the audience to find the humor in such a bleak story. Some of the Coens’ more broader comedies also are injected with some horrifically dark moments, showing just how masterfully the Coens can walk the fine line between the unsettling and the hilarious. A perfect example of that would be in the movie Burn After Reading (2008), where Brad Pitt’s dimwitted character Chad sneaks into the home of George Clooney’s equally dim Harry. When discovered hiding inside a closet, the funny moment suddenly turns dark as the startled Harry shoots Chad in the head in a very grisly and graphic way. By shifting the tone so dramatically, it actually punctuates the moment making it even more hilarious, just cause of the audacity of the Coens to go that extreme in the moment. That’s why their comedy works so well, because of the fearless way that they shock our sensibilities in order to get a laugh out of us.

3.

SHOT AND REVERSE SHOT

Something about the Coen Borthers’ style that might not be apparent to most viewers right away is the masterful use of one of cinema’s oldest techniques. Shot and Reverse Shot, or the practice of editing between characters to establish on-going action during scenes of dialogue, is a technique as old as cinema itself and is often taken for granted by most filmmakers. The Coen Brothers on the other hand use this technique to it’s full advantage by crafting their movies around it. Character interactions are key parts of any Coen Brother film, so it makes it more important to capture the little reactions each character makes in each scene, because it reveals a lot about them that the writing itself cannot tell. The Coens capture this by changing the rules a little bit with their framing. Most dialogue conversations between two characters in movies are usually done over the shoulder, putting both actors in the frame. The Coens put the camera in between the characters and capture each actor in a single composition. By cutting back and forth between the two actors, they are able to emphasize more of the reactions that each character gives the other in their conversations, and given the way they edit each scene, those different reactions can often determine the tone. Probably the most brilliant example of this is the Gas Station scene from No Country for Old Men, where Javier Bardem’s villainous Anton Chigurh asks the petrified proprietor (Gene Jones) “what’s the most you’ve ever lost in a coin toss.” Apart from a single insert of a candy wrapper, every moment in this scene is in one-shots of the two actors. The choices of how long to stay on each shot and when to cut back to the other determines the tempo of this whole scene, and it is a masterwork of building tension. By determining which character is focused on in each shot, the Coens establish how important their reaction must be, and thereby reveal more about what each one of them is thinking. By perfectly executing a technique that most of us take for granted, the Coens make their stories resound a whole lot more than they normally would, and it’s a testament to their skills as filmmakers.

4.

ROGER DEAKINS

The Coen Brothers often fill many of the most important roles themselves, but the one position that they rest heavily on the shoulders of someone else is that of the cinematographer, and they could not have found a better man for the job than Roger Deakins. Deakins is, apart from the Coens themselves, the one most responsible for crafting the look of a Coen Brothers film. Since first working with the duo on Barton Fink (1991), Deakins has been the cinematographer on almost all of their subsequent films. And even the movies of their that he didn’t work on, like Burn After Reading (shot by Emmanuel Lubezski) and Inside Llewellyn Davis (shot by Bruno Delbonnel) still retain a Deakins inspired aesthetic to them, showing just how much the Coens value his input. Roger Deakins style is a perfect match for the Coen Brothers, because it perfectly understates the style of storytelling they are after. Deakins often muted colors and faded lighting helps to define the bleakness of the Coen Brothers’ world, and his extensive use of wide-angle lenses help to make much of the real world details of the settings part of the focus along with the characters. It was because of him that the Coens put the camera in between the actors for their scenes of dialogue, because of his interest of showing the characters within their environment as part of each scene, making their uses of the Reverse Shot technique all the more effective. I also like how his choices of color grading help to enrich the setting of each film. When you look at the washed out colors of O Brother, Where art Thou (2000), or the Black and White photography of The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001), you get a strong sense of a bygone time that these two movies are trying to invoke. The Coen Brothers movies have a distinct look all their own, and it’s because of the valued input of a high class cinematographer like Roger Deakins that we can identify a Coen film from all the rest purely in a visual sense.

5.

UNRESOLVED NARRATIVES

One of the things that I love about a Coen Brothers’ movie is the fact that they rarely play by the standard rules of storytelling. Whereas most Hollywood films follow a simple three act structure, Coen Brothers movies tend to be much more flexible. This is mostly due to the brothers’ writing style, which relies less on pre-planning and instead involves them just writing scenes out and letting the story build out of that. This can be infuriating to viewers who just want a story to go somewhere familiar, but the way that the Coens build their stories as they go along actually feels very refreshing. And the unique thing that I noticed about a number of their movies is that they don’t resolve themselves at the end; at least not in a conventional way. Oftentimes, each story just seems to play out as a series of unfortunate events that ultimately change nothing about their main character’s life in the long run. In The Big Lebowski, Jeff Bridges’ Dude gets involved in a caper involving kidnapping and ransoms, but instead of him figuring the mystery out and triumphantly exposing the conspiracy around him, the whole plot ends up resolving itself without his help and he just goes back to the life he had before, apart from losing his car, his rug, and his friend Donny (Steve Buscemi) in unrelated incidents. Burn After Reading goes even further by stopping the movie cold right after John Malkovich’s character murders Richard Jenkin’s character with a hatchet. The scene shifts abruptly to J.K. Simmons’ CIA director literally closing the book on the crazy case told in the movie and simply asking, “What did we learn?” Sometimes this unconventional route can be frustrating, like Josh Brolin dying off-screen in No Country for Old Men, but other times it can be provocative, like the ambiguous Tornado finale A Serious Man, and it’s that ability to not take the conventional route that makes the Coen Brothers movies memorable in the end. I like that they don’t have to rely on happy endings, or have their characters transform by film’s end, because usually it’s those differences that make the story better.

It’s easy to see why the Coens are some of the most beloved filmmakers working today. Remarkably, they are two minds that have created a singular vision and it’s one that has maintained it’s own, uncompromising character over several, now classic films. They are celebrated the world over, with Joel Coen being the only 3 time winner of the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival (for Barton Fink, Fargo, and The Man Who Wasn’t There) and the duo being only the second team of Directors to ever win the award for Best Director at the Oscars for No Country for Old Men (the other two winners being Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins, sharing for West Side Story in 1961). The Coen Brothers have also had a long lasting legacy in cinema, with Fargo now adapted into a critically acclaimed series on FX. The Big Lebowski is also considered today to be among one of the funniest and most often quoted movies ever made, also turning the Dude into a cultural icon in the process. Regardless if you find their style appealing or not, each one of their movies is worth looking at; even some of the bad ones. I particularly think that the back-to-back masterpieces of Fargo and The Big Lebowski perfectly illustrate the brilliance of the brothers at the peak of their craft. The Oscar-winning No Country for Old Men is also a cinematic treasure worth experiencing. And if you haven’t seen it already, please watch their newest film Hail Ceaser, which is a near perfect love letter to classic Hollywood that any film buff will enjoy. Watching any film of theirs becomes especially interesting when you start to notice the common themes and stylistic choices that tie them all together, especially with their editing choices and their twisted sense of humor. It’s filmmakers like them that make it so enriching to look at their body of work as a whole, which I hope to continue with more beloved filmmakers in future articles like this.