Our own history as a civilization has provided Hollywood with countless inspiration for a variety of movies. And oftentimes, historical events are so monumental, that they inspire multiple interpretations. The same is also true with historical figures as well. The interesting thing about how Hollywood presents history on screen is that oftentimes the interpretation changes based upon the values of the current day. Heroes of older historical retellings can often be changed into the villains for more modern films. New historical evidence presented can even make us view the same events in a new light. Regardless of the truth behind the historical accounts, Hollywood has shown that the way we view history is as fluid as any other type of story-telling. Some of the most beloved historical films in fact play very loosely with actual history. Wildly inaccurate historical movies like Braveheart (1995) often get a pass because they have an emotional resonance that transcends the need to stay faithful to what actually happened. In many ways, it’s expected of Hollywood to not be historically accurate when making their movies, because in order to keep to a manageable two hour running time, elements of history will inevitably have to be changed, condensed, or just expelled completely to serve the story. The many different angles that can be taken with historical films leads to many interesting results, and it’s especially fascinating to look at how different films take on a real historical figure. Perhaps the most extreme recent example I can think of wildly different portrayals of the same historical figure would be the two films depicting the life of Native American icon, Pocahontas; the daughter of a Powhatan chieftan in pre-colonial America who was one of the first to encounter and interact with the European colonists. There could have been many angles to take with the character, but it’s surprising in the end that Pocahontas’ big screen identity is defined as a Disney princess in Pocahontas (1995) and as the subject of an art film named The New World (2005).

Cinematically, these two movies could not be more different. When Disney decided to take a shot at adapting Pocahontas’ story to the big screen, it was at a time when they were aiming high in the middle of their successful Renaissance period. Then studio head Jeffrey Katzenberg believed that Pocahontas could be the Disney Studio’s equivalent of a prestige picture. It was taken markedly more seriously than some of the other films from Disney Animation; with less of the usual Disney trademarks like talking animals (although there was still magical elements and musical numbers). It also took on headier issues like cultural intolerance, colonial exploitation, and interracial love, which you wouldn’t normally see in an animated feature. But, even with it’s higher ambitions, the movie only became a modest hit for Disney; grossing far under expectations and being overshadowed by the supposed “B-picture” that came before it (The Lion King). Some would argue that Pocahontas suffered from the historical liberties that it took to tell it’s story, while others would argue that it’s story was just not up to the same level as previous Disney films. More often, the former of the two complaints would win out. Historians were just not happy with the Disneyfication of real events and people, because they felt that it presented the wrong lesson and portrait of the person that Pocahontas was. Only ten years after, we were given yet another movie depicting the life of Pocahontas, only this time from art house icon Terrence Malick (The Thin Red Line, The Tree of Life). Malick’s take on the character felt truer to history in a production sense (with authentic locations and visual sense) but at the same time still felt like a big departure from actual history. So, do either of them stand out as a worthier interpretation? What I find more fascinating in comparing the two is not the ways that they are different, but the ways that they are similar, and how that better serves them as a cinematic experience.

“Come, spirit, help us sing the story of our land. You are our mother. We, your field of corn. We rise from out of the soul of you.”

Before we contrast the two films, we should probably look at the subject herself, and what her legacy has meant for the history of America. Pocahontas, or Matoaka as she was first named, was born around the turn of the 17th century in what is now coastal Virginia. Nicknamed Pocahontas, which in the Algonquian language means “playful one,” she was among the first native people to encounter the arrival of English colonists in North America. When the colonists arrived in 1607, they established the settlement of Jamestown, and not soon after began clashing with the native population. According to legend, one of the colonists named John Smith was captured by the Powhatan people and was brought forth to the chief to be executed. Before Chief Powhatan lowered his club, Pocahontas laid her body upon Smith to spare his life. This act of mercy is proclaimed as one of the moments in American history meant to represent an ideal of peace across cultures. However, the historical account is often called into question (Smith himself is the one who documented it), and harmony among cultures is something that didn’t really pan out for much of Native American history thereafter. But, what we do know for certain about Pocahontas’ life thereafter is that she left her life among her people and lived among the settlers, later marrying a tobacco farmer named John Rolfe. Her iconic status grew when she visited England years later and was brought before the court of King James as a representative of the “New World.” Her visit marked the first ever for someone from the Western Hemisphere to make it Eastward. Unfortunately, she contracted smallpox before she could make her journey home at the age of 21. Though her life was brief, her influence on native and colonial relations is still significant, and she remains a historically important figure in early American history.

Though well known in American history, Pocahontas has surprisingly not been the subject of many film adaptations. It’s probably because Hollywood has had a complicated history with Native American depictions. Like I stated before, the values of the times change, and for the longest time, Native American people were often portrayed badly in movies from the past; often playing the role of the villains in Cowboy flicks. As we’ve developed a better understanding of native populations in America, the need to present them with more dignity and respect has become much more essential. Disney, more often today, has been making an extensive effort to include more culturally diverse characters into their stable, and Pocahontas was their attempt to include Native Americans into the mix. While you can’t really state that Pocahontas is a princess like so many of the rest, she’s often given inclusion within the “Princess” product line that Disney has. Disney themselves were also guilty of less than flattering depictions of Native Americans in the past (the tribe in Peter Pan for example), so I can understand why they would want to embrace the character so much as part of their collection. But in doing so, did they undermine the significance of the person in American history? There can only be an answer to this by contrasting it with a more true life image of Pocahontas that we find in The New World. The Terrnence Malick film is not without it’s own liberties as well, but at the same time, it tries to do what few other movies have, which is to examine the world that Pocahontas lived within and attempt to understand how this shaped her into who she was.

“Pocahontas, the tree is talking to me.”

“Then you should talk back.”

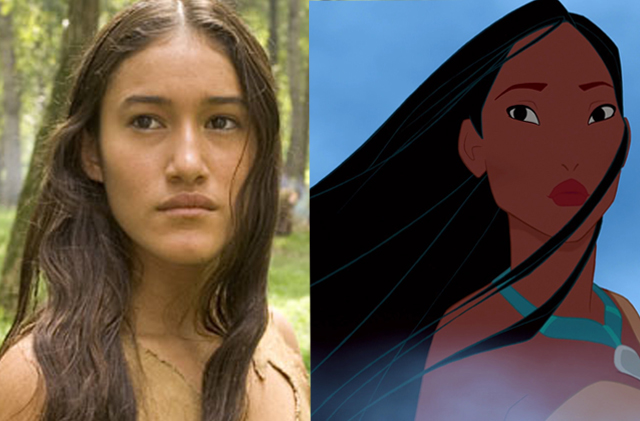

The character of Pocahontas comes across very differently in both movies. The two films do stress the identity of a free spirited individual. As one character in the animated version states, “She goes wherever the wind takes her.” In many ways, this is something that feels true to the actual person that Pocahontas was. Pocahontas bridged the gap between two cultures, and in order to do that, she couldn’t be entrenched in tradition and committed solely to her own racial identity. She had to see the changing times that were ahead and embrace the change that was coming her way; whether it was for the betterment of her society or not. This is handled a bit more delicately in the Terrence Malick version. Both films cast authentic Native American actresses in the role of Pocahontas, and in The New World, they went as far as to cast someone age appropriate as well. Then 15 year old Q’orianka Kilcher portrays a version of Pocahontas that feels very authentic. Though of mixed Incan and Swiss-German descent, Kilcher is close enough to the physical likeness of the real Pocahontas, whose only physical representation is preserved in a English made portrait from her final years. Her performance is also nicely understated, capturing the innocence of the young girl caught up in a turbulent time quite well. Though she often has to work through some of Terrence Malick’s sometimes dense poetic indulgences, her performance still gives you a sense of a maturing and awestruck pioneer. Disney’s Pocahontas, voiced by Native actress Irene Bedard, is a bit more heavy handed in her depiction. Though Bedard is exceptional in her vocal performance, it’s the writing that lets the character down. Disney’s Pocahontas changes little in the movie; starting off as stereotypically rebellious and naive as she begins to encounter the English settlers. It’s the downside of portraying a historical character within a highly fictionalized world like animation; you lose some of the subtlety. It makes her growth far less involving when she you have to buy into the fact that she’s speaking to an enchanted talking willow tree. Which is why I give the portrayal in The New World the edge here.

“There’s something I know when I’m with you that I forget when I’m away.”

I believe where historical critics took the most issue with the portrayal of Pocahontas’ story on film was in how it depicted the relationship between her and John Smith. In reality, Smith and Pocahontas were mere countenances who’s paths crossed briefly during the early days of the Jamestown colony. Like I stated earlier, John Smith is the only one who accounted for Pocahontas’ act of mercy, and he only shared it long after the fact. But, I guess for the purposes of cinematic licence, John Smith needed to be a stronger male presence, and in the case of Disney, I think they fell victim to their own formula here. Not only do Pocahontas and John Smith fill the lead roles in the animated film, but they also become romantically involved, in the fairy-tale romance kind of sense. While this is natural in so many other Disney movies, the romance is so awkwardly fixed into this story, especially when you know about the real history. In reality, John Smith was nearly 30 years older than Pocahontas, so Disney aged her up just for the purpose of giving her a love story and avoid controversy. Truth be told, the movie does handle it okay (it’s probably the most mature Disney love story we’ve seen to date), but it’s clearly the most blatant attempt by the studio to give this story a more conventional appeal. It would be more problematic if Disney alone was guilty of this, but surprisingly, Terrence Malick includes a romantic connection between Pocahontas and Smith as well. This is actually a bit more problematic in The New World considering it’s cast age-appropriately with the 15 year old Kilcher sharing a kiss with 30-something Colin Farrell as John Smith. While it’s out of place, the romantic angle is understandable from a filmmaking point of view, and Disney manages it a bit better by giving it more resonance. Also, Disney’s John Smith is a more charming lead (voiced by a pre-scandal Mel Gibson), whereas Colin Farrell was still in his awkward, trying too hard, Alexander era phase. In many ways, I feel Disney was unfairly singled out because of this, while Malick somehow was given a pass for doing the same exact thing.

But, perhaps the most striking difference between the movies cinematically is the way it uses the most defining moment of Pocahontas’ life; her self-sacrifice to save John Smith. The movies both spotlight the moment, but their placements are very different and because of this, it defines exactly what sets the different depictions apart. In The New World, the pivotal moment happens early in the movie, using it as a touchstone to set into motion all that would happen afterwards in Pocahontas’ life. In the animated film, it serves as the climax, bringing to head the collision between cultures that has been building up so far in the story. It’s a really interesting comparison, where you can see how the same event can serve as both the start and ending of a story, depending on how it’s used. In Disney’s Pocahontas, the heroine’s moment of truth stands in contrast to the growing racial tensions between her tribe and the Jamestown settlers. Her action inspires her father to reexamine his resolve to kill for vengeance and it in turn teaches everyone that peace between cultures is the better way. It’s a well handled statement and It’s clear why Disney waited for this moment in the film to bring the legendary action into the story. In contrast, Terrence Malick starts his narrative off with the moment of defiance, and then uses the rest of the movie to show the aftermath; how it affected the tensions between settlers and the natives, how it turned Pocahontas into a cultural ambassador, and how it moved her away from the culture of her youth. Essentially, Pocahontas’ act of mercy becomes one of many pivotal moments in the development of her character, rather than her defining moment. The New World essentially uses the story of Pocahontas a window into the experience of being in pre-colonial America, and it is there where Terrence Malick’s ethereal style kind of undermines the purpose of the story. Where Malick’s film wants to create an experience, Disney’s film is more intent on delivering a lesson, and a noble one at that. Neither is historically true, but in Disney’s case, it leaves you with a bit more to think about by film’s end.

“I’d rather die tomorrow than live a hundred years without knowing you.”

I guess in the overall picture, the surprising thing is not that Pocahontas’ life became the inspiration for film adaptations, but that her journey to the big screen manifested in such unexpected ways. An animated love story is something that I’m sure many historians never thought Pocahontas would find her way into. And for the cinematically experimental Terrence Malick to take an interest in her story as well is something that I’m sure very few cinephiles and historians alike would’ve ever thought would happen. And yet, we’ve ended up with two noteworthy and unique adaptations of Pocahontas’ life. Neither work very well as a history lesson, but they are interesting cinematic experiments regardless. I tend to favor Disney’s version over Malick’s. Despite all of it’s formulaic flaws, it’s heart is in it’s right place. I feel like Disney made the film as a means to right some of their earlier wrongs and give Native American cultures the same level of dignity as any other. I especially like how she is embraced today as among one of Disney’s most endearing Princess characters, despite the fact that she’s somewhat out of place in that category. The New World is also a flawed work of art that still has much to admire. The cinematography by Oscar winner Emmanuel Lubezki is unbelievably gorgeous, as is the production design. Malick’s poetic style may not be for everyone, but it can’t be disputed that his movies are beautiful to look at, and it’s interesting to see that style attached to Pocahontas’ story. I’d say watch The New World in order to understand who Pocahontas was, and then watch the Disney version to understand why she’s so important. They both serve their purposes, but the more resonant one will be the animated version. Sometimes historical liberties are essential to help us learn more about figures from our past. And in this case, Pocahontas evolved from a chief’s daughter, into an ambassador, to American icon, and is now viewed many years later as a princess. That’s history for you.

“You can own the Earth and still all you’ll own is Earth until you can paint with all the Colors of the Wind.”