When we want to watch a scary movie, we often seek out the films that have the most gruesome monsters or the most grisly of deaths. But one thing that I don’t think gets enough credit for making scary movies work are the settings themselves. The best horror movies have memorable monsters for sure, but it’s the location that makes them legendary as well. Setting helps to build atmosphere, drawing the viewer in by giving them the stage on which the horror plays out. Sometimes, it the setting that does most of the work, utilizing shadows and creepy sounds that both hide and spotlight the terror within. One thing that is noteworthy about all the various iconic horror films is that they usually take the standard idea of a scary setting and try different things with it. There’s no rule in horror that says that a horror movie needs to be set within a haunted house or even a spooky castle. Horror movies have made just about any place scary over the years, including schools, hospitals, amusements parks, and even nurseries. In fact, it almost works better to have a horror movie set in a usually safe space rather than a traditionally spooky one. There are plenty of great horror movies that do make use of the tried and true scary settings, like graveyards and haunted houses, and that why those places have continued to carry an aura of menace to them today. For this week’s upcoming Halloween, I want to list some of the greatest scary places to ever appear on film. I am only limiting this to locations that are purely cinematic creations, and not based on real places (like the Amityville house). Also, I’m opening this list up to scary places found in non horror movies as well, because some of those movies have frightening locations that stand shoulder to shoulder with the best found in horror. So, let’s take a look at 10 of the scariest places in movies.

10.

DRACULA’S CASTLE from DRACULA (1931)

Let’s start this off with the groundbreaking film that really cemented the visual inspiration for Hollywood Gothic horror for most of the industry’s history. Sure, Dracula was not the first movie to use setting to build spooky atmosphere. The German Expressionist movement had been utilizing groundbreaking techniques of light and shadow and Gothic design to frighten audiences for many years before, with iconic horror classics like Nosferatu (1922) and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). But director Tod Browning brought those techniques to the mainstream with Dracula and created the template on which decades of future horror films would be made. The gloomy, cobweb adorned castle of Count Dracula perfectly accentuates the chilling performance of Bela Lugosi in the title role, and helps to give us the feeling of unease that danger lurks within every nook and cranny of this place. The movie was made at a time when you couldn’t show any onscreen violence or blood, and even just implying the threat of violence faced scrutiny from censors. So, with Dracula, the filmmakers had to let the setting be the thing that frightened audiences and made them feel that ever crucial sense of dread. And they did this by implying the sense of decay of Dracula’s castle. It’s dark, empty, and rotten, and yet is still a threat to anyone who enters; much like the master who inhabits it. In the years since it’s release, you can see the fingerprints of Dracula in countless other horror movies, all of which still use the dusty, cobweb adorned interiors that worked so well before. Even Francis Ford Coppola’s big budget remake took much of it’s visual cue from some of the same techniques found in the original. It may not seem as scary today, but Dracula’s Castle from the original classic earns this spot just from the impact it’s had on the genre as a whole.

9.

BUFFALO BILL’S BASEMENT from THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS (1991)

Not every scary place in movies needs to necessarily be haunted; sometimes it just needs to house a truly horrifying monster. This was the case with The Silence of the Lambs, which has two such places that you could spotlight as among the scariest settings of all time. One of those places is the cell block that holds Hannibal Lecter behind bars (or in this case bullet proof glass). And though those scenes are terrifying on their own, I think they are edged out by the horror show that is the underground dwelling of serial killer Buffalo Bill. At least with the cell block, you get the feeling that the monster inside is neutralized to a degree, but in Buffalo Bill’s basement, we see his full, deranged life laid bare before us in a truly disgusting way. Most horrific is the dried up well in which he holds his victims captive before killing them and harvesting their skin. The movie’s most terrifying scenes show Buffalo Bill psychologically torturing his most recent captive as he forces her to apply skin lotion or else he’ll spray her with a garden hose, all the while calling her an “it” which shows the disconnected, dehumanization that plagues his mind. The dreariness of the setting is also very well realized, giving Bill’s living space this rotten feel to it. The fact that these scenes are also the only ones colored with sickly greens and oranges in the movie, which is mostly filmed in cold grays and blues, also sets it apart and shows just how unnatural it is compared to everything else in the movie. The whole setting may not be outwardly scary, but it puts the audience in a sense of unease that still effectively helps us dread every time the movie returns to it. Creepy is just as effective as horrifying, and that’s what helps to make Buffalo Bill’s basement on of cinema’s most terrifying places.

8.

SHELOB’S LAIR from THE LORD OF THE RINGS: THE RETURN OF THE KING (2003)

Proof that you don’t just find scary places in horror movies along. Peter Jackson’s epic fantasy trilogy based on the novels by J.R.R. Tolkein all have their fair share of memorable spooky locations; the mines of Moria, the tower of Orthanc in Isengard, the dead city of Minas Morgul, and even the expanse of Mordor itself. But none of those places carries the sheer terror that is found in Shelob’s Lair. The iconic scene from Tolkein’s novel is horrifically realized in the movie, with a remarkably grotesque representation of the massive spider who lives within it. What Peter Jackson brilliantly gets across in the film is the sheer terror of feeling like a fly trapped in a spider’s web, or in this case a burrow. After Gollum leads Frodo Baggins in the tunnel, we follow the harrowing experience through his eyes, and feel the same isolation that he feels. The most terrifying aspect of the scene is the disorientation that Frodo experiences, not knowing from which corner the massive spider Shelob is going to pop out from. The fact that even with all that extra weight, Shelob is still able to move with the same agility and speeds as a tiny spider makes the scene all the creepier. It’s not surprising to learn that Peter Jackson is arachnophobic by his own admission, and it’s apparent that he funneled all that fear and anxiety into this scene, effectively terrifying us in the same way he would be terrified. In a movie series already heavily populated with iconic and terryifying monsters, it really takes special effort to make something like Shelob rise above the rest, and the design of her lair really does a lot of help to make that happen. The isolation and wildness of it really sells the terror of the setting, giving us the sense that this is a place where even the most evil of creatures would not set foot in. And that as a result puts it in the same league as many of the scariest places from actual horror movies. Even fantasies can rise to that level of terror.

7.

THE FREELING FAMILY HOME from POLTERGEIST (1982)

The movie Poltergiest broke new ground in the horror film genre by moving away from the old fashioned template that had existed for years in Hollywood. It showed that a haunted house didn’t need to look rundown, broken and dilapidated in order to be effectively creepy. A haunted house, it turns out, could look just like any other suburban home. That’s the case with the Freeling family in this horror classic, as they move into a freshly developed new property with a house that has all the modern fixtures that a upper middle class household would want. But, over time, it becomes apparent that they are not alone, as all sorts of paranormal activity begins to terrorize them, even leading to the capture of the youngest child who gets trapped in the spectral plane with all the terrifying ghosts. This Tobe Hooper directed, Spielberg written film brings a sense of terror out of the audiences fears of witnessing a home invasion, only that the invaders are ghost. We feel safe in our homes, but the sense that this peacefulness can be broken by the supernatural really drives it home for audiences, who probably return home wondering if their living space might also be haunted. We do learn the source of the family’s haunting; their new neighborhood was built on land previously used a cemetery, and the greedy land developer moved only the tombstones and not the bodies underneath, desecrating the remains of many and angering their souls. But even without that explanation, the fact that a pristine new home can turn into a house of horrors is one that still leaves audiences in a state of apprehension. The impact of this movie is still felt in many modern day horror films, like the Paranormal Activity series, which uses the same aesthetic of a normal home violated by the presence of ghosts. More than anything, it’s terrifying because it gives us the dreadful sense that no place is safe in the end.

6.

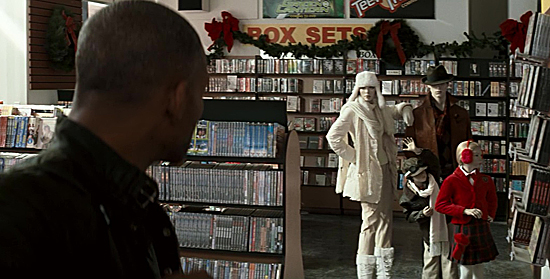

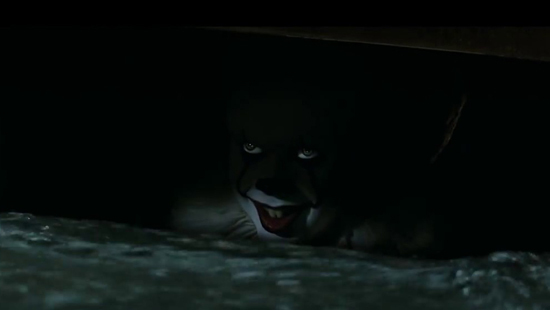

THE SEWERS OF DERRY, MAINE from STEPHEN KING’S IT (2017)

There is no doubt that the master of the horror genre for the last half century has been writer Stephen King. His endless string of novels have inspired a whole generation of writers and filmmakers to shape the current identity of the horror genre, and his books have also been the source for some of the scariest movies ever made. Probably most surprising is the fact that he still uses his home state of Maine as the setting for so many of these stories; which is odd because if you’ve been to Maine, there’s nothing there that really screams out to you as Gothic or spooky. For Stephen King, he ‘s created his own alternative Maine, which is the focal point of so much of the world’s evil and home to many of it’s most frightening creatures. One of the greatest creations of his horror mythology is the demon clown Pennywise, who is the focal point of the novel It (1986). King’s iconic novel has since spawned two classic adaptations; a TV mini-series starring Tim Curry as the clown, and last years big screen feature, starring Bill Skargard in the same role. Though the TV version is admirable, the movie does a much better job with making the setting truer to King’s vision, and that’s no more apparent than in the way it envisions the sewer dwelling of Pennywise. Much like Shelob’s Lair, the sewers create the disorienting feeling of entrapment and that the monster could be lurking just about anywhere. Thanks to the better resources from a larger budget, we are given a more surreal and terrifying setting that feels truer to the menace of the character. But to the original TV series’ credit, it does match the same creepiness with the movie when it comes to that introductory scene of Pennywise lurking up from a storm drain. Like what we read from King’s novel, it’s the darkness underneath the clown face that really is the thing of nightmares.

5.

THE PALE MAN’S DINING HALL from PAN’S LABYRINTH (2006)

Guillermo Del Toro has left his mark in numerous fields, such as science fiction (which earned him a coveted Oscar), fantasy and horror. Of those different genres, however, he feels more closely at home in horror, which is clear from his most direct cinematic and literary inspirations. An devout fan of the writings of Edgar Allen Poe and H. P. Lovecraft, Del Toro has often tried to fill most of his movies with creatures that stem from the darkest of nightmares, even if the movies themselves are not inherently scary. The most interesting visions of horror actually come from his trio of historical dramas set around or are influenced by the dark history of the Spanish Civil War. There are Cronos (1993) and The Devil’s Backbone (2001), both of which have their spooky elements, but it’s in the third feature, Pan’s Labyrinth, that we see his twisted imagination in full display. And in this film, we find what is probably the single most terrifying figure that the visionary director has ever conjured up in his entire career; the terrifying Pale Man. Played through breathtakingly detailed make-up by Del Toro regular Doug Jones, the Pale Man is a literal nightmare come to life. With it’s pale, drooping skin, monstrous teeth, and creepy eyeballs that it holds in it’s hands, it’s like no creature you’ve ever seen before or would want to see again. Paralleling this creature with the very human monster in the real world, the Fascist captain Vidal, Del Toro visualizes the nightmarish realities of his characters lives in a terrifying way, and this is emphasized very vividly in the Gothic decadence of the Pale Man’s banquet hall. Del Toro’s twisted designs extend from the character through the setting, and makes yet another dark web like others on this list ready to entrap it’s prey. Though briefly seen in the film itself, the Pale Man’s Hall is still scary enough to frighten our memories long after we’ve left it behind.

4.

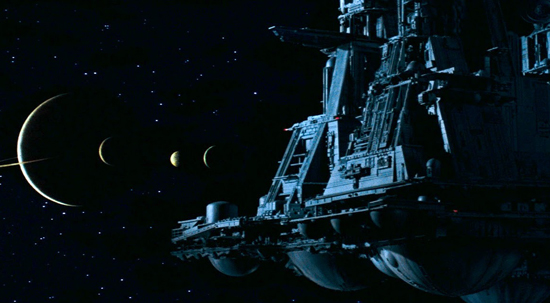

THE NOSTROMO from ALIEN (1979)

Ridley Scott’s Alien may seem on the surface like any other science fiction thriller, but there is plenty of things about the movie that owes more inspiration to the genre of horror. The cargo freighter space ship Nostromo is essentially a cosmic haunted house and instead of ghosts, we get a bloodthirsty humanoid alien. Scott manages to make the ship terrifying by using the same techniques used in horror; darkness and shadow, loud disorienting noises, and creepy scenery throughout every moment. The Nostromo is not some clean, pristine interstellar vehicle that you would find in an episode of Star Trek. It’s a beat up, unglamorous utility ship meant for shipping cargo. And the fact that it looks so dingy and corrupted helps to reinforce that sense of it being just as menacing to the main characters as the creature that hunts them from within it. There are some inspired moments where Ridley Scott stages some of the movie’s most frightening scenes, like a hanger where Harry Dean Stanton’s character is caught by the alien, with water leaking from nearby pipes and iron chains dangling from the ceiling. It really does make the scene feel like a haunted house, even though the setting is wildly different. The movie released with the tagline, “In space, no one can hear you scream,” so they knew the connection they were making with this. Ridley Scott did an effective job of melding genre tropes together to make Alien arguably the scariest science fiction movie ever made. And it all is due to the fact that they created a space ship that lends itself perfectly to that horror aesthetic. Other horror films set in space would follow in it’s footsteps, like 1997’s Event Horizon, but there’s no doubt that the Nostromo still holds that iconic place in Sci-Fi and horror fans hearts today. It’s still a place that makes us scream, even if it’s lost out in space.

3.

THE BATES MOTEL from PSYCHO (1960)

Alfred Hitchcock proved with the movie Psycho (1960) that not all scary places needed ghosts to be haunting. With the iconic Bates Motel as the setting for much of this movie, we see a very real depiction of the lingering effect that evil acts have on a singular location. The murders that occur within the unassuming walls of the hotel suites are shocking to first time viewers, who will probably come away worrying about the next time they stop for the night in while out in the middle of nowhere. The reason why the Bates Motel turns out to be so frightening in the end is because it’s true nature reveals itself to us quietly. The rooms themselves are accommodating, but the large Gothic house that looms over it projects that feeling of unease very quickly. The interesting thing about it is that the house is not where the danger lies. It’s a haunted house without a ghost. The real menace is the low lying rooms themselves, with the caretaker Norman Bates being the real monster. The Bates Motel is like a rattlesnake ready to pounce on it’s victim. The house looks ominous, but it’s just the warning rattle, as it’s the fangs that are really the danger. All that said, the Psycho house is rightfully iconic in it’s own right, and is enough to scare audience on it’s own. It still exists in it’s original state on the Universal Studio’s backlot and is still a highlight of the tour. The genius of Alfred Hitchcock was to present a false sense of anticipation on the audience’s part, as they never expected the Motel itself to be the real house of horrors. He created another icon of the genre by subverting the idea of safe zones, and showing us how evil can indeed lurk just about anywhere.

2.

REGAN’S BEDROOM from THE EXORCIST (1973)

There is no more terrifying idea than the invasion of evil into the most innocent of places. We see that played out to the extreme in William Friedkin’s iconic horror classic The Exorcist. The movie details the possession of a young girl by a particularly menacing demonic presence. As the movie goes along, we see the demon progressively corrupt young Regan (Lind Blair) and make her nearly unrecognizable by the end. That same corruption manifests itself as well into the room where she is kept. The bed she sleeps on is broken and the posts are padded in order to prevent any further damage to her body. As the movie goes on, all light and warmth is also removed from the room. All that’s left is minimal lamplight in an otherwise pitch dark room. And that effect perfectly constructs the very unsettling atmosphere that makes the film’s climatic finale so memorable. It’s disturbing to think that this once warm living space for a young, full of life child has devolved into this chilling battlefield between good and evil by movie’s end. William Friedkin makes this all the more effective by gradually changing the room over time, until it becomes the nightmarish setting of the finale. An extra special detail is found in the way that we see the breath of Fathers Karras and Merrin blow out when they speak, giving us the feeling of how cold it really is in that room. The stark lighting is another effective feature, taking cue especially from early German Expressionist techniques. But perhaps the reason that this setting is so memorably scary is because Friedkin made it feel so authentic. There’s no feeling of manipulation on the director’s part; no jump scares or visual effects. He puts you in that room with the characters and makes you feel the terror right alongside them. That’s what helps keep this little bedroom one of the greatest visions of hell on earth ever put on film.

1.

THE OVERLOOK HOTEL from THE SHINING (1980)

All of the places on this list have their own great effect on exploiting the fears of the audience. But none are more relentlessly frightening than those seen in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Another original creation from the mind of Stephen King, the Overlook is without a doubt single most terrifying place in all of cinema, and that’s because it’s shocking presence doesn’t come in just small doses; it permeates the entire movie. From the opening credits on, Kubrick puts his audience into a state of unease which doesn’t let up until the end, and even beyond that. The effectiveness of the movie comes from the feeling that there is no escape. Every corner of the Hotel is ripe for scary the hell out of us, and that’s largely because Kubrick broke one of the crucial rules of horror film-making. He casts every scene in bright light, making shadows non-existent. Most horror movies usually use a brightly lit scene to reassure a moment of safety for the characters, as all the shadows are the bastions of evil, lurking in places unseen to entrap our heroes. Because the shadows are absent in The Shining, there is a consistent sense of feeling that no place in the hotel is safe, and that is terrifying. There are countless moments in the movie that could rank high among the scariest of all time; like the confrontation between Jack and Wendy on the staircase, the chase in the hedge maze, the horrifying encounter in room 237. Perhaps the most iconic moment though is the appearance of the two twin girls at the end of the hallway, beckoning young Danny to come play with them. Again, it’s brightly lit without shadows and sneaks up on us the audience without warning, reinforcing the idea that not one part of this hotel is safe. King was not happy with Kubrick’s adaptation, because he felt that the movie minimized the evil of the hotel, but I would argue that Kubrick amped up the terror that was in the novel by making it so random and immediate. For all the scary places in other movies, they at least bring the audience back home to a sense of comfort. Kubrick dismantles that idea and gives us the most horrifying place in movie history with a setting where there is no place to hide.

So, there you have my choices for the scariest places in movie history. Some are certainly scarier than others that rank higher on the list, but the effectiveness of each is also what really matters. One pattern that I noticed from my own tastes on the subject is that the scariest places I observed are usually traps set by evil creatures to prey on the innocent. Whether it’s actual monsters like Pennywise from It and Shelob from The Lord of the Rings, or human monsters like Norman Bates from Psycho and Buffalo Bill from The Silence of the Lambs, the home bases of these different monsters often are terrifying reflections of the evil they embody. Of course, there are also the places that are transformed by evil acts like the house from Poltergeist or the Nostromo from Alien. And then you have just the relentless evil of a place like the Overlook in The Shining, which just leaves it’s dark mark on anyone unfortunate enough to be living within it. Whether it is haunted or not, a place often becomes an embodiment of our greatest fears and it’s aura permeates even beyond the evil deeds done there. This can be attributed to entertainment reinforcing superstitions throughout the course of history. There really is no real inherent danger when you walk through a graveyard, especially during daylight hours, but because they have this connotation with the supernatural, most people avoid venturing through them without reason. We give places the power to scare us, and it usually is the result of wanting to create a notorious reputation for something that is otherwise benign. And that’s something that has helped horror become as beloved a part of our collective narrative as anything else. It’s interesting to see that a dark past can be put on just about anything, and that’s evident in all the greatest scary places found in film. The ones from this list are perfect examples of that and there are plenty of more ways we can continue to scare one another by finding the mystery and terror found in even the unlikeliest of places.