Of all the different types of world cinema that has made it into the Criterion Collection’s library, the ones with some of the most interesting historical context behind them are those from Soviet era Russia. To say that Russian cinematic history is a bit complicated would be an understatement. Initially, post-Revolution Russia burst onto the scene as one of the most influential schools of film-making in the entire world. With the likes of it’s founding fathers including Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein, the Russian film industry pretty much invented the thematic montage as a means of telling a story through editing. That groundbreaking element alone helped to put Russian cinema on the map, and their revolutionary films like Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Man with a Movie Camera (1929) are still celebrated as masterworks that pushed the artform forward. But, the creative output began to change during the repressive Stalin regime, which saw the flourishing Russian cinematic machine turned to a purely glorifying the new hard-lined leader of the Communist Party. As a result, many of Russia’s great directors either found themselves heavily censored or those who would not submit could face death or exile. Many chose the later, including Eisenstein. Soviet cinema suddenly went from one of the most dynamic schools of cinema to one of the most restrictive. However, after the death of Joseph Stalin, the propaganda machine of the Soviet film industry evolved once again. They were still making propaganda, but the focus was instead on glorifying the Soviet people rather than one man. With the liberalization happening under the reforms of the Khrushchev regime, it became an era known as the Cultural Thaw. With it, there became a renewed desire to use the power of cinema as a means of breaking past the iron curtain of the Stalin years and showing to the world that Mother Russia could indeed hold it’s own in world cinema once again. This included a new push to bring forth fresh new talent in the Soviet schools of film, and one such talent to emerge was a burgeoning and ambitious new filmmaker named Andrei Tarkovsky.

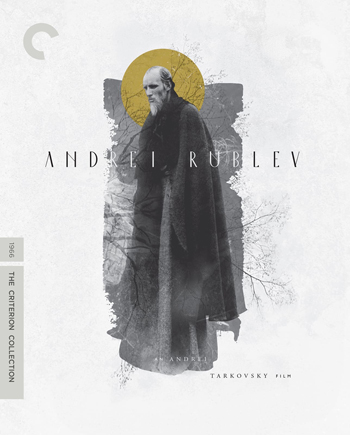

Tarkovsky, to many in the world of cinema, is considered to be the greatest filmmaker to have emerged out of post-Stalinist Russia. Even during his time, he was hailed as the best filmmaker to have come from the Soviet Union since Sergei Eisenstein, though the comparisons between the two directors couldn’t be more distant. Eisenstein’s films were intense, fast-paced dramatic pieces intended to inspire fury within the viewer. Tarkovsky was more contemplative, methodical and visually poetic as a filmmaker. Tarkovsky’s films are often ethereal and dreamlike, and he was a major influence on like-minded filmmakers such as Terrence Malick. Though very much a different kind of filmmaker than those of the post-Revolution era, Tarkovsky nevertheless helped to give a very Russian sensibility to what many saw as the New Wave movement of cinema that swept across Europe and over the world. Like other movies of that era, Tarkovsky’s films were both grandiose in concept and intimate in scale. Big ideas were at play in his films, but they always had that personal connection to them. He was a valuable voice for Soviet cinema, and he immediately emerged on the international scene winning the top prize at the Venice Film Festival with his first ever film, Ivan’s Childhood (1962, Spine #397). However, though he was lauded by his peers outside of Russia, he almost always faced resistance from his native country. Some in the Russian government found his films decadent and bourgeois and contrary to idealized values of the Soviet regime. Because of this, his filmography is very limited, limited to only a handful of movies made under heavy scrutiny in the Soviet Union, and only a few more made in Western Europe after his defection in the 1980’s, and cut short by his untimely death in 1986 after a brief battle with cancer. Still, as few as they were, his films are viewed as some of the greatest works of cinema ever created. Criterion has included a few in their collection, including the sci-fi epic Solaris (1972, #164) which some have called Russia’s answer to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). There are also the previously mentioned Ivan’s Childhood, and the late Russian films Mirror (1975, #1084) and Stalker (1979, #888). But probably the most interesting Tarkovsky film in their collection is that of what many consider to be Tarkovsky’s most ambitious film overall; the historical epic, Andrei Rublev (1966, #34).

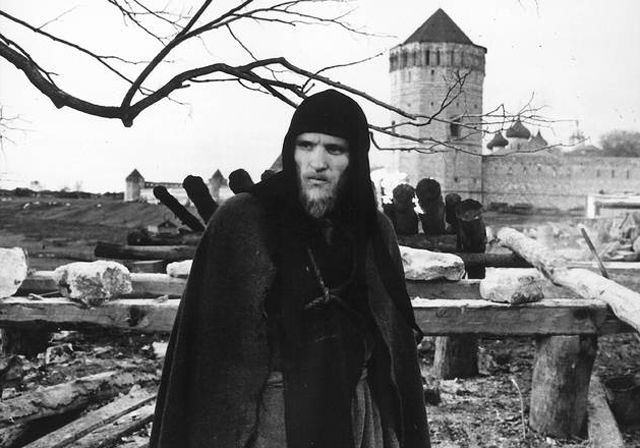

Andrei Rublev as a historical biopic is not the kind of movie that you’d expect it to be. On the surface it is meant to tell the story of the life of a legendary artist from medieval Russia. Andrei Rublev was a painter and monk best known for creating religious icons and frescos for the interiors of Orthodox churches throughout Russia. His work is largely considered to be among the greatest art created during the medieval period. A handful of his paintings still survive to this day, including what many consider to be his masterpiece, the Trinity. But, the interesting thing about Tarkovsky’s movie is that Andrei Rublev the man is not the focus of the film at all. Instead, the movie is more about the world that he lived in. The film Andrei Rublev finds the man himself (played by frequent Tarkovsky collaborator Anatoly Solonitsyn) passing through a series of vignettes of medieval life in rural Russia. Accompanied by his fellow monk companions Kirill (Ivan Lapikov) and Danil (Nikolai Grinko), heads to the workshop of Theophanes the Greek (Nikolai Sergeyev), who intends to have Rublev assist him on a commission to paint the new Cathedral of the Holy Ascension in Moscow. Along their journey they encounter a small village that is entertained by a jester (Rolan Boykov) who later is captured by the authorities for mocking their leader. Later, they find a group of pagans partaking in a clothing optional ritual, who also later are captured by puritanical authorities. Once at the cathedral, Andrei finds it hard to express his art effectively, seeing how medieval Russia has become so hostile to the acts of free expression. Later, a raid by invading Tartar barbarians lays waste to Moscow, and the ruling prince is deposed by his traitorous cousin, who then usurps the crown. In the chaos that ensues, Theophanes is slaughtered, the cathedral is in ruins, and Andrei was force to kill in order to save the life of another. Because of the trauma, Rublev stops painting and takes a vow of silence, retreating from the harsh new world. However, his lack of passion for life changes when he witnesses the creation of a massive bell being forged by a craftsman named Boriska (Nikolai Burlyayev), who is just a teenage boy. Upon seeing such a beautiful creation come from such a young person of humble beginnings, it reawakens Rublev’s desire to create, and the film ends with a prologue showing us all the iconic artwork that has immortalized his name ever since.

Andrei Rublev indeed is a very different kind of epic. For one thing, it does have all the expected scale and scope of a traditional historical biopic, especially from the same era that gave us the likes of Spartacus (1960) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962). But, narratively it is completely different. Like I mentioned before, it’s a movie about multiple stories depicting life of medieval Russia, with only Andrei Rublev himself being the connecting thread. It is also very much a movie built around imagined history and not actual history. All the film gets right about it’s subject is that he was a painter of religious icons and that he lived in medieval Russia. The rest is all fiction. For the most part, it seems like Andrei Tarkovsky wanted to make a movie that was a meditation on the connection between art and the artist rather than historical recreation. Andrei Rublev is not so much a driving force on the story as he is a cypher; observing the world around him and having that influence the person he will eventually be. Though the main character remains an enigma as a result, it surprisingly actually works in the movie’s favor. It’s a movie about exploring the nature of art; why it’s important for the individual and for society as a whole. You can see this as a definite statement that Tarkovsky wanted to make to his fellow Russians in the middle of the Cultural Thaw, as so many of them were reawakening to the idea of using their cultural works as a means of defining what it meant to be Russian. The paintings of Andrei Rublev themselves gained a renewed sense of importance in those post-Stalin years, as Russians wanted a better sense of their cultural history to define who they were, rather than just the Revolution. For Tarkovsky, art was an essential part of cultural awakening. It’s most clearly stated in the climax of the movie, where the forging of the bell becomes the thing that renews Rublev’s faith. Great art inspires other great art, and Tarkovsky believed that this was something important to pass down through generations. The Stalin years stifled the artistic growth of Russian society in Tarkovsky’s eyes, and he saw a connection between the art of the past and the present as key to defining what it meant to be Russian. Of course, the artistic fervor he shared wasn’t always welcomed by the power of the state. With a movie that especially questioned authority and even entertained a very positive religious outlook, it was unsurprisingly heavily scrutinized by the Soviet government. The film’s original 205 minute cut was trimmed down with the supervision of Tarkovsky after it’s premiere, but further edits were made by the government, and it would be many years before Tarkovsky’s true vision would be fully seen by the public.

But, despite the headaches that the Soviet censors were giving him, Tarkovsky nevertheless was lauded from cinephiles all over the world, and Andrei Rublev is largely seen as his masterwork. Narratively, it is probably his most accessible film, given that most of his later films turned more cerebral and elusive. But, given that, it’s an interesting film to watch because it does turn the historical epic genre on it’s head a bit. The episodic nature of the story underlines for the audience that this is less a dramatization and more of parable of art, society, and humankind that just so happens to be based on real history. Every segment of the film feels like it’s own short story, revealing a variety of different characters that make up the defining attributes of Andrei Rublev’s world. It’s interesting that Tarkovsky opens his film with a cartoonish prologue of a man taking flight after getting caught in the ropes of a hot air balloon. It’s silly to begin with, but ultimately it’s implied that the man meet a tragic end as he plummets back down to Earth, perhaps giving us an indication of what to expect through the rest of the film. The moment otherwise feels unconnected to everything else. The whole movie is filled with these little asides that reflect little on Andrei Rublev the character other than helping us to see how the world with all of it’s absurdities ends up shaping the man and his art. The one scene that overall does reveal some character growth in Andrei is the climatic formation of the massive bell. In that scene, where Rublev witnesses a young boy inspiring a whole community to create something grand and beautiful, we see his reawakening come to full fruition. But, where Tarkovsky really sells home the point of the film is when Rublev finds the boy Boriska weeping after the completion of his master work. He hold Boriska in his arms and learns that the boy learned nothing from his master, and that he was just winging it the whole time, making him feel like a fraud. In that moment, Rublev realizes that he must reaffirm this boy’s faith in his ability to create, and in turn, it reaffirms his own faith as well. For Tarkovsky, the cycle of creative inspiration was essential for making great things happen. It’s what he wanted for all cinema in general, that he would inspire other filmmakers to create at the same level as well, both at home and abroad and that it in turn would help inspire him to do more as well. Tarkovsky was an artistic optimist, believing that the desire for creation transcended national identity and politics, and it’s something that certainly made him stand out in the Soviet film industry. Though the higher ups did not concur with Tarkovsky’s global view of the artform, he nevertheless made a point that this art is the thing that truly leads to immortality, as evidenced by the lasting impact of Rublev’s centuries old paintings.

For the Criterion Collection, adding Andrei Rublev was key to their drive to preserve the history of cinema all over the world. It was the earliest film of Andrei Tarkovsky’s to enter the collection, dating all the way back to the days of laser disc. An earlier DVD edition featured a rather rough looking transfer of the original 3 1/2 hour cut of the movie known as The Passion According to Andre, which they managed to source from a print found in the Mosfilm archives. This long version itself was a revelation for film fans here in the United States, because all we had for years was a heavily edited down version released by Columbia Pictures. Here, we were seeing the controversial original version that was especially hated by the censors of the Soviet cultural ministry. It was a popular title for Criterion for many years, helping to establish Tarkovsky’s reputation as one of the great masters. But, when Criterion started publishing blu-ray discs, many wanted to not only see Andrei Rublev get an upgraded presentation, but also one that fully brought the film back to a glory that most people never got to see before, other than Tarkovsky himself. In collaboration with Mosfilm, the Moscow based studio that originally produced the film, a new high definition digital master was created from a restoration of a 35mm internegative struck from the original film. The results are pretty remarkable, bringing the black and white film back to near flawless clarity, while still maintaining the grainy texture that helps to give it a cinematic texture. Keep in mind, the Russians didn’t have quite the same quality of film stock that the West did, so there is far more signs of age still found in the picture, but for a film made under those kinds of elements, it still holds up for a movie of it’s era. The same is true for the film’s soundtrack. Soviet films do indeed sound very different from most Western film, as most of the dialogue, sound effect and music sound detached from the picture; maybe a side effect of using different equipment. The sound restoration does the best job it can to help everything sound as natural as it can, with the dialogue benefitting the most from a crisper, clearer refinement. What is especially impressive is that both Mosfilm and Criterion completed restorations for two different cuts of the movie; the previously mentioned long version, and the shorter, 183 minute post-premiere version that was actually the one Tarkovsky preferred the most. Both are included on the blu-ray and it’s interesting seeing how different the two versions play.

Also included on the disc are plenty of interesting bonuses, which delve deeper into both the making of the movie, as well as the legacy it has left behind over the years. One of the most interesting features is a documentary made during the development of the screenplay called The Three Andreis. Made by a classmate of Tarkovsky’s from the film school VGIK named Dina Musatova, the documentary is about the prep work put into the making of the movie, focusing on screenplay written by two Andreis named Tarkovsky and Konchalovsky, and the actor who would play Andrei Rublev, Anatoly Solonitsyn, getting into character. It’s a fascinating first hand look at the film in it’s early stages. There is also another vintage documentary included that actually shows Tarkovsky and his crew on the set, made by Mosfilm itself as promotional piece to spotlight the film during it’s making. The set also features a newly created documentary that features retrospective interviews from film scholars Louis Milne and Sean Martin, as well as the film’s cinematographer Vadim Yusov and actor Nikolai Burlyaev who played the bell maker Boriska. One interesting insight revealed by Burlyaev in his interview is that he based much of his performance as a tortured artist on director Tarkovsky himself. The legacy of the film is also further examined with new interviews featuring film scholar Robert Bird and filmmaker Daniel Raim. In lieu of a full length commentary track, this edition includes a select scene audio commentary by film scholar Vlada Petric from the original 1998 laser disc. And for those curious, the blu-ray edition also includes the thesis film that Tarkovsky made in film school back in 1961, titled The Steamroller and the Violin, showing the filmmakers humble beginnings before he was thrust onto the world stage. Given that Tarkovsky’s body of work was so truncated compared to many of his contemporaries, having his earliest film presented here is important in giving us a more fuller understanding of how he became the cinematic artist that we all know. In a way, Criterion is doing the same here, showing an the awakening of an artist in his early years before his grander work, that Tarkovsky himself did for the memory of Andrei Rublev. This in general helps to really make this a very special blu-ray set to own.

Andrei Rublev really is a unique film in the history of Russian and world cinema. It had all the trappings of a grand historical epic on the level of something out of Hollywood, and yet narratively it was subversive and antithetical to the genre itself. Andrei Tarkovsky certainly had the vision grandiose enough to stage an epic on the level of some of the greats of that period, with a keen eye for staging big shots and giving his movie an authentic period look. But, at the same time, he uses his cinematic eye to tell a story different from the one we expect, and tell it in a way that’s more about feeling one’s way through the narrative rather than following it in a linear way. Rest assured, Tarkovsky’s style is definitely not for everyone. Most of the movie features long, meandering shots of nature with almost no dialogue at all. And lots of random shots of horses too (a Tarkovsky tradmark). Don’t go in expecting to learn a lot about who Andrei Rublev was. In a way, it’s not really important to the story that Tarkovsky wanted to tell. It’s a movie less about the artist and more about the world he inhabits. Tarkovsky said that we learn our history from the artists that observed it, and indeed some of our only insight into what life was like for medieval Russians is through the surviving artwork of Andrei Rublev. That’s why he closes the film with a montage of close-up views of the master’s paintings, presented in full color (the only part of the movie presented that way). The art endures long after the man and the society that inspired him has passed away. Tarkovsky believed too that this was an essential lesson to learn in a society that he believed was loosing it’s connection to the past and how important it was to connect with the rest of the world through the art we create. Indeed, his work has long outlived him and we continue to talk highly of him as a filmmaker because of how celebrated movies like Andrei Rublev are even half a century later. It’s truly remarkable to note that Andrei Rublev was only his second feature as a director. Though he would continue to make more films after, none have the same massive scope as this one does. Though it breaks many rules of the historical epic genre, it nevertheless still feels big with it’s widescreen presentation and ambitious story. The less ethereal second half, which includes the Tartar sacking of Moscow and the forging of the bell chapters, do liven up the movie and show the director at his most dynamic, but the contemplative first half with dream like moments feel far more personal to the director’s own sensibilities. It’s a beautifully complex and rule-breaking film to include in the Criterion collection and one that firmly places Tarkovsky as one of the most interesting voices spotlighted within the Collection.