The Gothic Romance has long been a popular genre in Western literature. We often pass by the bookstands at our local stores and see these often laughable looking book covers of two impossibly beautiful characters embracing against a stormy skyline. As omnipresent as these kinds of titillating novels may be in book stores across the world, they nevertheless have been instrumental in shaping literature as we know it. The gothic fiction has it’s origins in early 19th century literature, which helped to cement the very Victorian era elements in so much of the novels we see today. It was in this literary movement where authors like the Bronte sisters, Jane Austen, and Mary Shelley flourished. In their works, they used Gothic imagery (such as dark castles, forests, or hidden passages) to inject a bit of forbidden anger into their stories, which in it’s own way turned into subversive escape for female readers. For the writers themselves, it was a way to break away from the standard male centered marriage stories that often defined Victorian literature at the time. These kinds of novels helped to elevate the voices of women in literature, as gothic romance often were the only outlets that allowed women to voice outrage over violence committed against them by framing it within these darker themed stories. These were stories by women and for women, but even beyond that connection, these kinds of novels would have a profound effect on the presentation of gothic themes overall in storytelling over the next century. As the genre evolved into the 20th century, more authors found ways to adapt the genre to more modern readers, and in turn, refresh the Gothic genre with even more taboo elements in their stories.

One such author who modernized the Gothic romance for 20th century readers was Daphne Du Maurier. Du Maurier was an English author who worked primarily within the genre, often taking the gothic elements to near supernatural levels in her writing. She was greatly influenced by the Bronte sisters, as many literary scholars see parallels with her stories and those of the legendary writers like Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre. She wrote almost continuously over a 40 year period, including novels, short stories and plays. But it’s her earlier work in the 30’s and 40’s that she is most remembered for. Novels like The Loving Spirit (1931), Jamaica Inn (1936) and My Cousin Rachel (1951) often involved young heroines who have their lives upended by tragedy, mystery and even a little bit of spectral haunting. She was a master of creating a sense of dread throughout her novels, with the oppressive melancholy of the often gloomy English weather being a pervasive element. A critique of many of her works was that she often made her stories too depressing, with her novels often denying the reader a happy ending. But, even as her writing was frequently dreary and foreboding, she also remained a very popular author. Critics didn’t warm up to her novels initially, but the average reader loved her subversive style and the way that she challenged their sensibilities. Of all of her books, the one that undeniably remains her seminal work is the novel Rebecca (1938). The novel was an immediate success upon publication, and naturally gained the immediate interest of Hollywood. A movie adaptation was begun even as the first edition of Rebecca remained on book shelves, and it would begin an interesting story all of its own, as it would launch a whole new chapter in the career of one of cinema’s greatest filmmakers, which also led to a tumultuous behind the scenes clash in it’s own right. The film adaptation of Rebecca also shows an interesting experiment in Hollywood could work around it’s limitations in order to do justice to a challenging source material.

“Last night, I dreamt I went to Manderley again.”

The film rights to Rebecca were bought up immediately after publication by one of the biggest personalities in all of Hollywood; David O. Selznick. The “take no prisoners” producer was already in the middle of his magnum opus film adaptation of Gone With the Wind (1939) when development began on Rebecca. The latter may not have been as epic in scale as the former, but Selznick was still determined to turn Rebecca into his next big hit after Wind. Being another sweeping romance that was a hit with readers, there was no doubt that Rebecca would be an ideal production for Selznick to take on, but it would require a different kind of filmmaker in order to get the more Gothic elements of Du Maurier’s story right. That filmmaker would turn out to be a rising star out of the British film scene. Alfred Hitchcock had been making a name for himself across the pond with critically acclaimed thrillers and mysteries such as The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), and The Lady Vanishes (1938). And for years, Hollywood had been calling for him to cross over and bring his talents to Tinseltown. But, given that many of the offers that came Hitchcock’s way were just standard Hollywood dramas, the more Gothic minded filmmaker often refused to make the transition. But, once Selznick secured the rights to Rebecca, the offer could not be passed up. For Hitchcock, Rebecca was exactly what he was looking for, with it’s taboo subject matter, Gothic setting and themes, and tension filled mystery. He not only agreed to make the film, but Selznick also managed to talk him into a multi-film contract at his studio; a decision that Hitchcock later would regret. But, there’s no denying that the marriage of Hitchcock’s direction and Du Maurier’s writing was perfect match. Indeed, the finished film does display the standard Hitchcockian brilliance, though you can also sense the intrusive meddling hand of Selznick at play as well, and it lead to some interesting changes to the story in contrast to what appears in the book.

“Why don’t you go? Why don’t leave Manderley? He doesn’t need you. He’s got his memories.”

Certainly one of the most important things that Hitchcock and Selznick needed to accomplish to do justice to the novel was the casting of the characters. In particular, they needed to pick the right actress for the never-named protagonist. One of the most interesting choices in Daphne Du Maurier’s novel was that she tells the whole story as a first person testimonial from her female protagonist, and never once shares that character’s name. The heroine, whose credited in the movies as just “I,” is meant to be the audience’s surrogate for this tale, and leaving her unnamed is an interesting bit of experimentation on the part of the author. The film carries that over, but apart from opening narration, the character must be able to stand out without having an identifiable moniker. For casting, the movie found it’s ideal heroine with Joan Fontaine. The English actress, and sister of fellow Hollywood legend Olivia de Haviland, is a perfect embodiment of Du Maurier’s protagonist. She is strong willed but also effectively haunted in her performance, able to make the character resonate within the movie. She is also a perfect match for the brooding presence of Laurence Olivier as the dashing millionaire widower Maxim de Winter. Olivier had already become a household name a year prior with his star making turn in the Hollywood adaptation of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights (1939), but Maxim’s tortured persona would be a big difference for the actor after the strong willed Heathcliff. Olivier very much welcomed the role, seeing the hapless Maxim as a great contrast to his other noteworthy role, which showed Hollywood that he had more range, which would help the Shakespearean trained thespian break free from typecasting that so many actors would fall into during those studio system days. For both Olivier and Fontaine, this was a good risk taking opportunity that helped to strengthen their opportunities as performers, rather than just as actors, something common in British cinema but not so much in Hollywood.

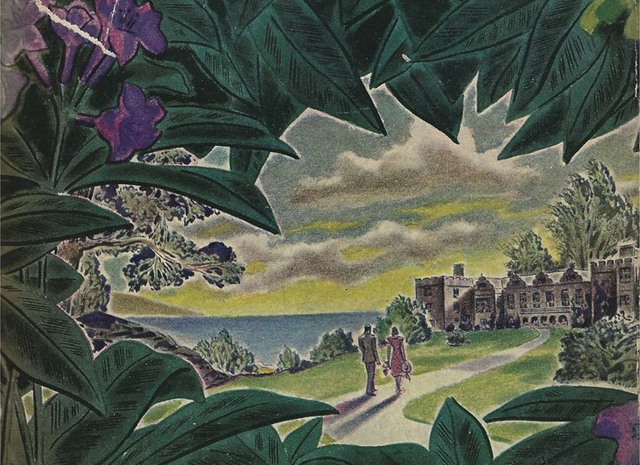

But what made it necessary to have someone like Hitchcock on board was for presenting a presence on screen for someone who is never actually seen; the titular woman. Maxim de Winter and the protagonist waste no time falling in love and they marry before the first act is even over. Where Du Maurier’s story really kicks into high gear is when Maxim brings his new bride home for the first time, to the mighty manor house known as Manderley. The Manderley manor is a character within the novel and the film in it’s own right, an ominous Gothic mansion full of history that in time comes to overwhelm the new bride. And in particular, the mansion bears the omnipresent memory of Maxim’s first wife, Rebecca. While there is no actual ghostly presence described by Du Maurier within the story, the way she describes the cold, oppressive feeling of Manderley often gives the reader a feeling of the place being haunted. Hitchcock perfectly captures this as well in his direction. Drawing upon his history of making tension filled thrillers back in England, Hitchcock gives Manderley this foreboding feeling, using the contrast of light and shadows to great effect. Working with a Hollywood sized budget, he even gets to work on a scale he hadn’t been able to have before. The actual Manderley house in the film doesn’t exist, and was created through highly detailed models, which was necessary given how the needed to have the mansion destroyed by the end of the movie. But the sets themselves also go far in helping to accentuate the ghostly feel of the setting. The great halls have this domineering castle like feel to them, but when you see the bedroom that once belonged to Rebecca, it’s ethereal like with it’s billowy see-thru silk drapes. It all helps to reinforce the idea from Du Maurier’s novel that even though Rebecca is dead and gone, her presence still dominates the house that Maxim’s new bride must now live in.

“I watched you go down, just as I watched her a year ago. Even in the same dress you couldn’t compare.”

One of the other things that Hitchcock also perfectly translated from the novel, and perhaps even improved upon, is the character of Manderley’s domineering housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers. Mrs. Danvers is one of the most memorable villainesses in 20th century literature, and she seems to have been a favorite of Alfred Hitchcock’s too. Played magnificently in the film by Australian actress Judith Anderson, Mrs. Danvers is the figure in the story that most actively allows the memory of Rebecca to endure. Her intent from day one is to make the new “Mrs. de Winter” felt like an intruder into Manderley, but she does so with carefully applied gaslighting under the guise of being a good caretaker. She reinforces in the mind of the protagonist that Rebecca is and will forever be the love of Maxim’s life, and that the best course of action for her is to leave Maxim and break his heart or take herself out entirely. It’s through the character of Mrs. Danvers that both the book and the movie approach it’s most taboo and challenging subject matter. Many scholars have theorized that Mrs. Danvers devotion to the memory of Rebecca has more to do than with just what’s on the surface. Though it was has never been substantiated, it was thought that Daphne Du Maurier was bisexual, and had same-sex love affairs in her past. If true, it might have been something that informed her writing with regard to Mrs. Danvers’ motivations in the story. A same sex attraction, and even a hidden love affair, is hinted at very much between her and Rebecca in the story, and it carries over into the jealousy that she holds for the protagonist. In some ways, the gaslighting done towards the protagonist carry a little bit of grooming as well, which for a story like this was very taboo for it’s time. Naturally, Hitchcock had to tread lightly with this subject matter, as censors would not allow for any hint of same sex relationships mentioned in any movie at the time. Of course, for a filmmaker like Hitchcock, and even Selznick to some extant, boundaries are there to be tested, and they certainly took it as far as it could go.

The movie does stick pretty close to the novel, until it does clash with the Production Code standards that all of Hollywood had to stand by. The code forbade any explicitly sexual material, even in innuendos, and made especially strict guidelines in how acts of violence should be depicted in movies. Apart from censoring the implications of queer subtext with some of the characters, the movie also had to gloss over the moral shades of gray when it comes to the characters. In the novel (spoilers), we learn that Maxim’s haunted demeanor over the thought of Rebecca is not because he loved and misses her, as the protagonist suspects, but because he in reality hated her and was responsible for her death. In the book, Maxim confesses to shooting Rebecca in a secluded fishing cabin by the beach and throwing her body out into the sea afterwards. The Production Code wouldn’t allow for film to have it’s male lead responsible for killing his wife in cold blood, so in the movie, the death was changed into an accidental death, with Rebecca implied to have smashed her head open on the exposed end of an anchor during a physical fight with Maxim. Both incidents do push Maxim towards his guilty conscience, but the movie version definitely makes the moment feel more sanitized and ludicrously convenient. We of course learn in both cases that Rebecca was already dying from a terminal illness, and she coaxed Maxim into killing her as part of her death wish, but the moment feels much darker in the original book. Du Maurier’s penchant for tragic endings also gets changed in the movie as well. Manderley is set ablaze by Mrs. Danvers, but the novel treats it as shocking final act that ruins the lives of all. In the movie, both Maxim and the protagonist live, but Mrs. Danvers receives her comeuppance in the inferno; a victim of her own obsession. To Hitchcock’s credit, he makes this tacked on ending memorable in it’s staging, with a haunting final look on Judith Anderson’s Danvers face as the inflamed ceiling of Manderley comes crashing down on top of her. But, the more bitter finale of Du Maurier’s novel does a lot more towards creating a haunting final note to leave the story on.

“It wouldn’t make for sanity, would it, living with the devil.”

The confluence of Du Maurier’s writing, Hitchcock’s direction, and Selznick’s showmanship led to a brilliant cinematic adaptation of this classic novel, even in a compromised state. The gamble definitely paid off, but unfortunately it was David O. Selznick that took all the glory. Rebecca would go on to win the coveted Best Picture award at the Oscars that year, the only film of Hitchcock’s to ever achieve that honor, though he himself never received the award for Best Director throughout his career, despite frequent nominations. Sadly, because of the success of Rebecca, Hitchcock was further locked into his contract with Selznick, leading to a contentious decade ahead where both director and producer clashed frequently. The upside, however, is that it firmly established Hitchcock as a force in Hollywood, where he would go on to create some of the greatest movies of all time like Rear Window (1954), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), and of course Psycho (1960). Hitchcock would even revisit the writings of Daphne Du Maurier again when he adapted one of her more supernatural short stories into a classic thriller known as The Birds (1963). Unfortunately due to his contentious working experience with the domineering Selznick, he would later dismiss Rebecca as one of his lesser works towards the end of his career. Du Maurier didn’t feel the same way, and over time she celebrated Hitchcock’s adaptation as one of her favorite adaptations of her novels, even with all the alterations. To this day, Rebecca the novel and the movie still represents one of the best examples of Gothic romance from the 20th century. The atmosphere, tone, and risk-taking elements all work together to make it a story that has stood the test of time and can still leave it’s audience captivated. As a piece of woman’s literature, it’s also ahead of it’s time, and it’s interesting how this story is driven first and foremost by the women within it. The protagonist doesn’t have a name, and the woman whose name makes up the title is only mentioned in the past tense, and yet, they drive the narrative more than the male characters, who this time are cast as the passive players in this story. A full 80 years after it’s original publication, Daphne Du Maurier’s novel and the Hitchcock film it inspired are still feminist narratives that feel as relevant today as they ever have been.

“Do you think the dead come back and watch the living?”