Stanley Kubrick is no stranger to literary adaptations in his body of work. In fact, the bulk of his filmography is sourced from previously published works of literature; from best-sellers like Stephen King’s The Shining (1980) to obscure novellas like Arthur Schnitzler’s “Traumnovelle” which was the basis for his final film Eyes Wide Shut (1999). And all of those adaptations range from faithful, to completely divorced from the original text. For Stanley Kubrick, it’s always been the stories that have captivated him the most, or to be more exact, how the story can be shaped through his vision. Kubrick was always a visual filmmaker first and foremost, so the appeal of these stories more or less based on how they formed within his own imagination. That’s probably why he was so drawn to the futurism of Arthur C. Clarke, or the unflinching war stories of Gustav Hasford, or the class critiques of William Makepeace Thackery. More often than not, Kubrick’s stamps on these stories become so iconic that the stories become more identified with him than with their original authors (such as with The Shining, much to King’s dismay). But if there was one film where the author’s voice still manages to shine through even with Kubrick’s vision, it is with Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange (1971). It was a bit shocking when Kubrick decided to adapt Burgess’ 1962 dystopian novel about violent street thugs and authoritarian regimes as his follow-up to his massive space opera 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). It wasn’t unusual for Kubrick to adapt controversial novels to the big screen, like he had with Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1962), but A Clockwork Orange had since it’s original publication been known to be a notoriously hard to adapt to the screen as well as controversial for it’s content, which was scandalous for it’s time. Still, Kubrick saw something in the story that appealed to his tastes as a filmmaker, and with the surprising backing of a major studio like Warner Brothers, he set to make the un-filmable filmable.

Anthony Burgess, the author of A Clockwork Orange, never saw himself primarily as a creative writer. He was foremost a musician and a scholar, finding vocation in linguistics, where he would provide translations for various literary and musical works from around the world. In his time as an academic, he would write satirical works, which often ran afoul of the social establishment in England at the time. In the early 1960’s, Burgess suffered a health scare, where he was misdiagnosed with having a brain tumor. Worrying that his time would run out soon, he frantically put his writing skills to work to create a novel that he hoped to sell before his death in order to give his wife support after he was gone. The tome was completed in a remarkable three weeks, and not soon after, Burgess learned that he was not in fact dying. Still, he had a book now that he could sell and it would end up becoming the the novel that he would be forever known for; A Clockwork Orange. Based on a real event that occurred to Burgess and is wife during the London Blitz, where they were robbed and assaulted in their home by deserters from the American army in the blackout, Clockwork Orange was a dark, satirical look at the extremes of society. Those extremes would of course be the fanatical violent indulgences of an un-disciplined population of youth and the authoritarian over reach of law and order trying to pacify it. Essentially it was a novel examining the exercise of free will, and the fine line that society walks between freedom and order. Burgess ultimately had written a novel that would cause controversy, but to what extant he didn’t know. Many critics believed that his novel, with it’s frank depictions of sex and violence, were almost endorsements of those kinds of actions. The novel is entirely told through the eyes of it’s young “ultraviolent” protagonist, who for long passages in the novel relishes in the horrific actions that he undertakes. But, with Burgess putting us in the POV of such a violent character, he is also asking us to consider what the best course of action would be right to deal with such a character. As we watch his re-habilitation through his perspective, Burgess is making us consider the idea that the solution may be even worse than the problem.

“Real horrorshow! Initiative comes to thems that wait. I’ve taught you much, my little droogies.”

It is interesting to examine Kubrick’s take on the writings of Anthony Burgess in the film A Clockwork Orange, because out of all his adaptations, this is the closest Kubrick has ever gotten to making a film exactly like the source novel. Initially, Anthony Burgess was commissioned by Warner Brothers to draft a screenplay for Kubrick, but the director ultimately declined to use it. Apparently, Burgess’ screenplay was even more violent that the novel. Ultimately, Kubrick would adapt the book himself, and some would argue that he barely even followed his own script on set. Sometimes he would just show up on set with the novel in hand, and plan his scenes based on that. That’s why when you read the book and watch the movie, you will see almost complete parity. There are of course some minor tweaks that Kubrick made to get the source material to a point where it met his vision. One of the very obvious changes was in the ages of his characters. The protagonist of A Clockwork Orange, a hoodlum teenager named Alex, commits horrific acts like violent assaults, robbery, rape, and even murder, and all at the age of 15. This, of course, wouldn’t fly with any film studio, so Kubrick made the choice to age up Alex to a young man on the verge of adulthood. The same goes for his victims, as some of them are also underage in the book. But, even with that, the film maintains nearly every other aspect of the novel; from it’s first person narrative point of view, to it’s near futuristic setting, to the graphic depictions of sex and violence which in it’s day earned the film the ever dreaded X Rating. Yet, even with it’s risky nature, the film was success in it’s time, and probably to an extent that worried both Kubrick and Burgess in the years to come.

“FOOOD….ALRIGHT?”

One of the aspects of the movie that wins praise from the literary community is the incredible realization of the character of Alex. Alex DeLarge, as he is named in the film, is one of the most fascinating characters to have ever been put on screen. The success of the film largely is due to how well the character works on screen, considering that it all revolves around him. One of the things that mattered in the casting of the character was finding an actor who could embody the entire arc that the character goes through, from the out of control delinquent that we literally meet in frame one to the broken down reformed young man who struggles to adjust in a world that he had a hand in making worse. For the part of Alex, Kubrick found his ideal performer in young actor Malcolm McDowell. McDowell, who was in his mid-twenties at the time of filming, managed to embody the anarchic teenage fury of the character to perfection. What probably helped McDowell land the part was his breakout performance in English filmmaker Lindsey Anderson’s If…(1968), where he played a rebellious student at a stuffy English boarding school. McDowell would proved to be not just right for the part, but he even brought elements to the character that made him stand out from the page even more. Apparently, the now iconic white uniforms with bowler hats black boots, and codpieces that Alex and his gang of “Droogs” wear in the film were inspired by Cricket gear that McDowell would come to the set wearing. Another thing that Malcolm is famous for bringing to the film is an entirely improvised scene where Alex and the Droogs attack an author (played by Patrck Magee) and his wife. The moment from the book is clearly inspired by the real life incident that Anthony Burgess endured, but Stanley felt it needed something more, so he asked Malcolm to do a little dance while he was in the middle of the attack. Malcolm, as a result broke into a rendition of “Singin’ in the Rain,” making the already horrifying moment all the more darker with the inclusion of such a cheerful song. After shooting the scene, Kubrick got on the phone and called Warner Brothers to secure the rights for the song, knowing that Malcolm had made the perfect subversive choice.

One other thing that is remarkable about Malcolm’s portrayal of Alex in the film is that he was able to master the unique language of Burgess’ novel. Anthony Burgess invented a special dialect spoken by Alex and his gang called “Nadsat,” which is a combination of Russian and Cockney slang. Not only did the Yorkshire born and raised Malcolm have to wrap his mind around this unusual new accent, but he had to do so as part of the character’s inner monologue as well. The effect works out really well, as it makes Alex even distinctive within the film amongst the other characters also speaking this new dialect. Malcolm gives Alex’s inner monologue this eerily sinister tone, which shows that even as his violent tendencies are suppressed by his reform, the dark aspect of his character is always still there underneath. A lot of the Nadsat dialogue that is found in the novel is something that may given the novel the reputation of being un-filmable, so it is interesting to see Kubrick not only embrace it in his adaptation, but also keep it intact word for word. In many ways, the dialect is key to the satire of the story, as it is representative of the social divisions between generations that drive the people in the story to their extremes. The authoritarian government types that mean to suppress Alex’s violent tendencies speak with an authoritative and refined tone, much in contrast to Alex’s free-wheeling slang. But of course as we see in the novel and the film, civility is not necessarily defined by the manner in which the character speaks. The upper class and highly educated types in the novel, from the government officials to the doctors conditioning Alex during this treatment, to even the radical political writer all have their own evil ends on which Alex finds himself in the middle of. For Burgess in his writing, he is showing that no one is blameless in the story; Alex is more a product of the evils of polite society rather than just an anomaly within it.

“The pain and sickness all over me like an animal. Then I realized what it was. The music coming up from the floor was our old friend, Ludwig Van, and the dreaded Ninth Symphony.”

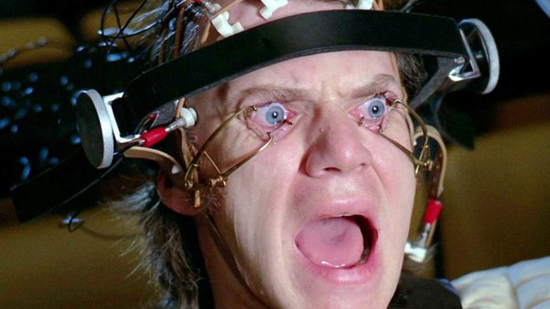

One of the interesting aspects of the novel is seeing how the extremes play against each other. We see Alex for the monster that he is from the beginning, and know from the start that he is a character beyond redemption. But, Burgess also challenges the idea of how we must as a society respond to such a monster. In the story, Alex undergoes a treatment called the Ludavico Technique, which is a form of behavioral modification done through aversion therapy. Mainly, it involves Alex being subjected to images of violent actions while being administered a drug that induces sickness, thereby causing him to revert to sick feelings whenever he feels a tendency to act in a violent manner. Unfortunately for him, while they are administering the treatment, he recognizes the background music as that of his favorite composer Beethoven (“Lovely Ludwig Van”). As as result, the same treatment now renders him docile with his favorite music as well; which is even more torturous for him. Both the novel and the movie do an effective job of portraying the benign evil of this experimental treatment, and the de-humanizing aspect of it. As much as Alex is deserving of punishment for his crimes, the Ludavico Technique is portrayed as an especially gruesome form of torture. It for one is especially shocking to see actor Malcolm McDowell strapped to a chair with his eyelids clamped open, and have it not be a special effect. McDowell really put himself through that, and the clamps at one point did really scratch his eyeball, which he thankfully recovered from. But one can’t help but watch that scene and feel unease about what is being done to Alex. As bad as he is, the solution should not be equal or worse to the crimes committed. And this is what Anthony Burgess intended his readers to think about. He must of thought of horrible things that he wanted to see done to his attackers, and then he began to self-reflect on what that reveals about him. A society too comfortable with violence as a response to violence is one that he saw as especially perceptible to authoritarian leanings.

What may be the most monumental difference between the book and the film is the famous “missing chapter.” Anthony Burgess’ original novel is comprised of 21 chapters. Broken into three parts, the 21 chapters show the progression of Alex’s character from out of control youth, to pawn of the state’s response to the problem of violence, to ultimately a victim himself. The book’s title comes from the cockney phrase, “queer as a clockwork orange,” which provides an even deeper meaning as the main argument of the novel itself. The idea of a “clockwork orange” is the absurd idea of taking something that is supposed to grow organically and force a mechanical working upon it. Mainly, a “clockwork orange” is something, or someone, who has been forced to change their own nature in order to conform to society. The movie follows this aspect from the novel, except for the end. In Burgess’ original novel, the final 21st chapter finds Alex returning to his old ways after the treatment wears off. But, as he has a run in with one of his old Droogs, who has changed on his own to live a better life, it makes Alex reconsider his own choices. And the novel concludes with Alex finally choosing to change; with his own free will and not through the influence of social pressure or forced treatment. In this final chapter, Burgess states a hopefulness for humanity, where even the worst kinds of people are capable of change, if they are allowed to naturally grow up. Kubrick on the other hand leaves out this final chapter, which was also excluded in the published version in the United States. Kubrick’s interests were more geared towards the corruption of the society that forced it’s morality on Alex while not addressing it’s own evil inclinations. The movie concludes with Alex reverting back to his old ways, but not with the hopeful note of personal growth. In a way, it makes the movie more cynical than the book with regards to it’s view on violence, showing that the opposite sides of Alex’s anarchy and the oppressive government meaning to eliminate him are in for a never-ending cycle. In some ways, the oppression possibly made Alex even more inclined to villainy, as he sinisterly claims “I was cured alright.”

“Goodness comes from within. Goodness is chosen. When a man cannot choose, he ceases to be a man.”

Despite winning acclaim upon it’s release, Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange proved to be a little too potent for society at the time. A string of gang violence took off in the months after the film’s release in Great Britain, with some of the thugs imitating the likes of Alex and the Droogs in their crimes. Kubrick was so worried about the effect that his movie was having, that he took it upon himself to have it pulled from exhibition in Britain, and the film would remain out of print in the U.K. for the rest of his lifetime; though it still was widely available in the U.S., where it developed a classic status. Anthony Burgess did praise Kubrick’s work on the film adaptation, but in later years he tried to distance himself from the film and the novel, believing that it unfairly painted him in a scandalous light. Over time, people have come to recognize the film less as a dangerous, exploitational film and more as the darkly comic satire that Burgess intended it to be. There will still be debates over whether Kubrick was right to excise the more hopeful final chapter, but there is little doubt that he created a masterpiece that has greatly withstood the test of time. From that unforgettable first opening shot (one of the greatest in cinematic history) in the Korova Milk Bar, to the anarchic energy of the film’s opening act, to the way that Kubrick uses music in his story telling (both in the classic renditions as well as the synth modified recordings by composer Wendy Carlos), the movie is a film that continually surprises in every scene. Of all of the adaptations that Stanley Kubrick put onto film, Antony Burgess’ writing feels more in line with his tastes as an artist than anything else he has made. It’s like the two were meant to be; Kubrick needed a story with a voice as unique as Burgess’ and Burgess needed a visionary eye like Kubrick’s to make his world come to life. And of course the unforgettable performance by Malcolm McDowell helped to make Alex an icon of cinema that will forever be remembered. You just know that you’re in for a wild ride when the first thing you see after the titles is the main actor staring creepily right down the barrel of the camera lens. Kubrick’s artistry makes a statement to be sure, but the message from Burgess about the need for free will in the human experience also shines through, even with all the extremes. Viddy well, little brother. Viddy well.

“Great Bolshy Yarblockos to you.”