There are very few filmmakers out there who left quite the impression that the late William Friedkin had made, both behind the camera and in front. Part of the young crop of filmmakers that rose up in the late 60’s and early 70’s as part of the “New Hollywood” movement, Friedkin was a maverick in every sense of the word. His unglamorous, documentarian style was so unlike what the rest of the industry was making, and it grabbed a hold of audiences in a way that took many industry insiders by surprise. He was also a brash, opinionated auteur who was not afraid of speaking his mind, even when it would burn a bridge or two with other creative collaborators. But there was no one in all of Hollywood, even among his detractors, who denied Friedkin’s talents as a filmmaker. He has gone on to become one of the most influential filmmakers of the last half century, with directors like John Singleton singling him out as a particular inspiration in their work. And though the New Hollywood era came to an end with the dawn of the age of blockbusters in the 1980’s, Friedkin would continually still find work both inside and outside of Hollywood. In addition to being a part-time film school instructor (including at my own film school Chapman University, though sadly before my time there), Friedkin would continue to direct small films for the big screen as well as for television, and remarkably enough was also a director of operas both in his home base of Los Angeles and for the National Opera in Washington. Even in his final year, he was still working on what would be his final film, Showtime Network’s The Caine Mutiny Court Martial (2023), showing that even at the age of 87 he remained a tireless storyteller.

Friedkin was born in 1935 in Chicago, Illinois to a family of Jewish Ukrainian emigrants. Given the person he would become one day, it may be surprising to know that he didn’t see his first film until he was 16. But the movie that introduced him to the art of cinema would be a profound one and it would shape the course of the rest of his life. That film was Citizen Kane (1941) by Orson Welles, and anyone familiar with Friedkin’s filmography will undoubtedly find the aura of Kane looming large over Friedkin’s particular style. Friedkin became a true cineaste afterwards and he spent much of his young adulthood indulging in the masterworks of that time period, both domestic and foreign. Eventually, upon graduating high school, he gained a position working for the local Chicago WGN television station. After working his way up from the mail room, he was granted the chance to direct programming for the station. Friedkin would excel as a documentarian in those years, winning accolades and awards for documentaries like The People vs. Paul Crump (1962) and Mayhem on a Sunday Afternoon (1965). Eventually, he grabbed the attention of movie studios who were looking to make use of his talents as a director. He initially started out with a Sonny and Cher movie called Good Times (1965) which he later described as “unwatchable.” But, this experience did lead him towards directing an adaptation of the Mart Crowley play The Boys in the Band (1970). Though Friedkin is not gay himself, he is lauded by the LGBTQ community for directing the first mainstream film to contain positive portrayals of queer identity, and Freidkin over the years did consider it one of his own personal favorites. But, what came after may be one of the best back to back triumphs of any filmmaker in Hollywood ever. He would go on to direct the crime drama The French Connection (1971), which would be an astounding hit that ended up sweeping the Academy Awards, including a win for Willaim who at the time was the youngest Best Director winner ever at the age of 35. To follow that up, he directed the horror themed The Exorcist (1973) which even to this day is still one of the highest grossing films in history adjusted for inflation. Of course, astounding heights soon lead to depressing lows, and Friedkin’s follow-up, Sorcerer (1977), despite being an impressive cinematic achievement was also plagued by production problems and was unable to make-up it’s colossal budget at the box office. Friedkin’s remaining career would experience ups and downs, but it never quite returned to the height it had in the early 70’s. But, it never got Freidkin down as he remained active all the way up to his passing earlier this year. In this article, I will be taking a look at all of the important factors that made a William Friedkin film stand out in the cinematic crowd.

1.

DOCUMENTARIAN STYLE

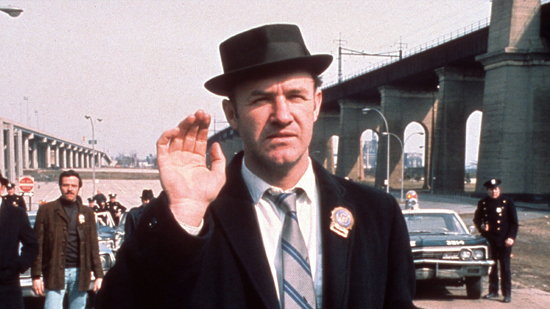

A lot of filmmakers carry the tricks of the trade that they started out with along with them as they create their body of work over time, and William Friedkin is no different. From a filmmakers style, you can tell if they started off as a commercial director, a television director, or a documentarian before they got into narrative film. Friedkin was definitely the latter, and it’s that documentarian spirit in his film-making that really makes his style stand out. Every movie he made has a very voyeuristic feel to them, like the camera has unexpectedly captured a moment. Friedkin’s films make particularly heavy use of hand held photography, which are especially present in his action scenes. While Friedkin didn’t invent the first person car chase sequence on film (Bullit had done that back in 1968), his team did take it to the next level. The car chase in The French Connection is one of the most wild and visceral action sequences ever put on screen, with Friedkin upping the ante by having Gene Hackman’s Popeye Doyle chasing an commuter train. The whole sequence has a chaotic feel and that’s because Friedkin is shooting the sequence with any artificiality involved. Real cars on real roads, with the camera right there in the passenger seat. For Friedkin, cinema was about getting as close to reality as possible, even if the story was something supernatural like The Exorcist. And the documentarian in Friedkin’s style can even be found in the quieter dialogue moments, as he often shots his subjects from far away with shallow depths of field, again like he’s catching a moment rather than staging one. Though the scales of his movies changed over time, Friedkin still would use his documentarian instincts in most of the films he made over the years. His groundbreaking French Connection car chase scene would inspire similarly impressive action scenes in his later films like To Live and Die in L.A. (1985) and Jade (1995). Friedkin would also continue to create the occasional documentary, including 2007’s The Painter’s Voice and 2017’s The Devil and Father Amorth. Documentaries was the language of cinema where he found his voice, and it’s something that he carried with him all the way through his career.

2.

CONTROLLED CHAOS

One other thing that comes from a documentary background is the sense of letting the unexpected happen in order to create a magical moment on film. This is something that certainly has it’s rewards, but also it’s consequences as well on a movie set. Ever the maverick filmmaker, Friedkin would often make his movies with a sort of reckless abandon, hoping to create very naturalistic results for his film. In many cases, this would bring his cast and crews dangerously close to the edge. There are many stories from the sets of his movies of near death experiences and on set injuries. That previously mentioned car chase from the French Connection was notoriously shot in some instances without a permit, making it illegal and dangerously hazardous to unsuspecting pedestrians that may have gotten a little too close to the shooting location. There is one shot that made it into the movie where the stunt car has to quickly swerve out of the way of a pedestrian, and you see the car jump a curb, hit a trash can and nearly miss the camera by just a couple feet. This is a chaotic way to make a film, but the end result is one of the most famous chase sequences in movie history. Friedkin likewise used some extreme tactics on the set of The Exorcist. Young Linda Blair experienced minor injuries from the ropes used to flail her around on the bed during her exorcism scene, and actor Jason Miller also violently confronted the director after he fired a gun near his ear in order to get the right startled reaction from him. These were pretty extreme measures taken in order to create the amount of authenticity that Friedkin desired for his films. No one would argue with him, as long as the results panned out. This mode of filmmaking eventually came to a head with the filming of Sorcerer, William Friedkin’s big budget remake of Henri Georges-Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear (1953). The film is celebrated today as a colossal achievement in filmmaking, but Friedkin’s chaotic instincts got the best of him as the movie’s production turned into an over-budget mess that couldn’t recoup at the box office, showing his limits for the first time in Hollywood. Most of the movies he made since then would try to replicate the action dynamics of his early years, but he would do so without the same amount of chaos, keeping things smaller and more controlled.

3.

FLAWED, AMORAL PROTAGONISTS

Apart from his attraction to darker themed movies, Friedkin also was drawn to stories centered around imperfect characters. While a lot of Hollywood dramas wanted to leave the viewer with a good sense of good triumphing over evil, Friedkin liked to view the deeds of people who operate within shades of gray. The main characters in his movies are often people just skirting on the edge of the right side of the law and are not so easy to root for from the start. No character better exemplifies this than Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle from The French Connection, brilliantly portrayed by Gene Hackman in an Oscar-winning performance. Hackman plays Doyle as a brash, unorthodox cop with violent tendencies and often a very racist attitude. At the same time, we also see that he is the best person for the job in hunting down the villainous French drug kingpins that are plaguing his city. Most of Friedkin’s movies would follow along with main characters that exemplify these moral gray areas, because in Friedkin’s worldview, there is no such thing as a pure hero. These are real characters and like all real people, they have character flaws that make them far more interesting and individualistic. The story then becomes how well the characters overcome their flaws in order to succeed in the end. This is definitely true of all the characters in Sorcerer, where their initial motivation is greed but ultimately by the end it becomes about survival. Some of Friedkin’s characters in the later part of his career also fall on different sides of that moral gray area. In The Hunted (2003), the movie comes down to a battle of wits between two battle weary killers played by Tommy Lee Jones and Benicio Del Toro. Matthew McConaughey plays both sides of the law in Killer Joe (2011), as both a cop and an assassin. Even the purer characters in his movies carry some kind of baggage with them that keep them from being just purely good and moral. That’s true of the two priests in The Exorcist, Father Karras and Father Merrin (Jason Miller and Max Von Sydow respectively), as both are experiencing their own crises of faith in their own way as they try to summon the strength to battle an otherworldly evil. It’s clear that Friedkin was never interested in the traditional standard of characterization from Hollywood, where good and evil was so black and white. And that’s why he’s so celebrated now as a storyteller as his characters stand out as uniquely amoral.

4.

THE “CITIZEN KANE” SHOT

There is something in William Friedkin’s style that very much owes a lot to classic Hollywood, and it’s something that harkens back to the movie that made him from the very beginning. To his dying day, William Friedkin stated that Citizen Kane was his all time favorite film, and it shows very much in his body of work. In particular, there’s something within Friedkin’s movies which has become known as a “Citizen Kane” shot. In Citizen Kane, Orson Welles would accentuate the largeness of his character by shooting many scenes from low angles; so low in fact that special trenches had to be dug on the set for the cameraman to get as low to the floor as possible. As a result, you see something in Citizen Kane that is often out of view in most movies, which is the ceiling. William Friedkin loved this kind of camera angle so much that he frequently used in most of his films. When the camera isn’t handheld in a scene to accentuate the action, Friedkin will often have it still and low to the floor, helping to still maintain that voyeuristic element. While there is at least one of this kind of shot in the majority of his movies, it’s The Exorcist where you see the “Citizen Kane” shot deployed the most. He keeps the camera low for most of the movie, which may have been a necessity given the fact that they were shooting in a real home for most of the movie as opposed to a soundstage set so space was likely limited. At the same time, it gives an extra sense of claustrophobia as the visible ceiling boxes the scene of the exorcism in all that much more. That confined feeling really elevates the violence on screen too, as the demonic paranormal activity of things flying around the room feel reminiscent of Charles Foster Kane’s violent outburst at the end of Citizen Kane, again with the low angle making the moment feel all the more visceral for the viewer who feels trapped. It is beautiful to see the full circle of cinema as one cinematic classic is responsible for inspiring another in an unexpected way.

5.

FEROCIOUS VIOELNCE

Violence is another crucial ingredient in William Friedkin’s movies. But, unlike a lot of other action movie directors, he never once glamorizes his violence. If anything, he wants the viewer to experience how truly ugly violence really is. In his films, every violent act is shocking and brutal, even if it isn’t always bloody. This is definitely true of the controlled chaotic movies of his early career, where there is a crazed manic energy to the violence in those films. The most violent parts of The Exorcist achieve the effect that Friedkin desired, which is to make you feel uneasy and afraid. It was reported at the time that many people would faint in the theater watching The Exorcist because of the sheer amount of unrelenting shock the viewer would go through in the movie. As film standards loosened around what was acceptable with on screen violence, Friedkin would continue to push the boundaries to their limit. His late career films are a great example of how he was trying to go as far as he could with on screen violence. The Hunted features some very visceral moments of violence, particularly in the climatic riverside brawl between Jones and Del Toro. Bug (2006) brought in the kind of claustrophobic insanity that you can find him recalling the close quarter violence of scenes from The Exorcist. And Killer Joe became that rare movie to be slapped with an NC-17 rating for it’s violence. But never once does Friedkin try to indulge and glamorize in any of that violence. It’s always treated as an ugly action, and his use of it within his movies is part of his attempt to capture a sense of realism within his scenes. There really is no other director out there who makes the spilling of blood on screen feel more real and personal than William Friedkin and it’s something that really has made him stand out as an influential filmmaker.

I have talked before on this site many times about my attendance for many years at the annual TCM Classic Film Festival in Hollywood. While there are many memories that I cherish from my time at the festival, some of my favorite moments are the ones that William Friedkin was a part of. I feel so fortunate to have seen William Friedkin live in person at the festival not once but twice, for screenings of The French Connection and The Exorcist especially. The Exorcist screening in particular stands out as one of my all time favorite festival experiences, as Mr. Friedkin shared an hour’s worth of stories and anecdotes from his experience working on the movie. It was amazing seeing this filmmaker well into his eighties still manage to captivate an audience just through telling his own story on stage. He was long winded to be sure, but we the audience didn’t care, because his stories were just so fascinating to listen to. There is no doubt that he lived a wild life, and that is clear from the movies that he left behind. He certainly was not a perfect human being, given some the controversial ways he made his movies, but at the same time perfection was never something he valued. He was perhaps the best personification of what we knew as “New Hollywood;” a filmmaker who sought to break all the old rules and turn cinema into something different for a new generation. At the same time, he was a man that still had a reverence for classic cinema; in particular for the films of Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock. He remained a champion for the movies all his life, and it’s satisfying to see that he did indeed leave an impact. So many action films today owe a debt to the innovations he made as a filmmaker, especially with the documentarian, in the middle of it style that he applied to the violent moments within his movies. It’s also worth revisiting a lot of his film analysis from his scholarly years, especially when you see him getting especially salty in some interviews. The man was just as much of a character in real life as the ones he put up on screen. I will definitely miss his presence at the festival screenings, and I feel honored to have been there for the ones that I did see him attend. He was certainly a giant in the history of cinema, and he thankfully never grew out of his reputation of being a maverick filmmaker.