The horror movie genre isn’t exactly known for being the place to find great acting. Given the lower costs that most horror films are made under, it usually relates to a lower quality of performance seen on screen. Bad performances in horror movies usually are attributed to the level of quality of the actor themselves, who perhaps are acting in front of the camera for the first time. Or there might be a good quality actor in a role that is very much ill suited for them and they are just there to collect a paycheck. Either way, horror movie sadly do not get the same good fortune that other genres get when it comes to showcasing the talents of the actors. But, there are cases when great performances can coincide with some truly terrifying movies. Even in some of the cases where a horror movie is clearly done on the cheap there can be an example of a performer giving it their all and treating schlock like it’s Shakespeare. There are in fact some performances that have transcended the genre and have been heralded as among the greatest of all time. In a couple cases, there are even Oscar winning performances that came from horror movies. For a genre that is as old as cinema itself, it’s understandable that many actors have looked to the dark side to find a role that really allows them to flex their acting muscles in ways that other genres don’t allow them to. For this list, I am going to share my choices for what I think are the top ten most terrifying performances to have ever come from horror movies. To be on this list, the performance can’t just be a great but not scary one that happened to be in a horror movie. The performances on this list are ones that genuinely send chills down the spine of audiences while at the same time showcasing just how good the actor is in playing the part. And in some of the cases on this list, the roles have been so unforgettably terrifying, that they still stick with us many years later. So, with all that laid out, let’s take a look at my picks for the Top Ten Terrifying Performances in Horror Movies.

10.

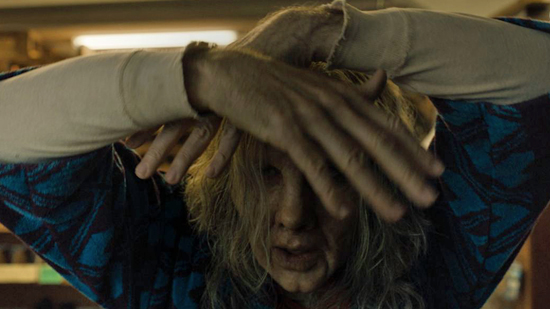

ANNIE GRAHAM from HEREDITARY (2018)

Played by Toni Collette

Not every performance in a horror movie starts out as terrifying. Some evolve over the course of the movie and by the finale turn into the things of nightmares for audiences. One of the most vivid portrayals of a slow burn descent into the terrifying can be found in Ari Aster’s Hereditary, where actress Toni Collette delivers one of her most stellar performances in a career that’s full of great ones. The character of Annie Graham is on the surface a grieving mother, who not only lost her own mom with whom she had a complicated relationship, but also her daughter in a horrific accident, all in the span of a couple of days. But, as the movie moves further into the plot, we begin to see Annie unravel in an unsettling way, lashing out at the family she has left and going to extreme measures to reconnect herself with the loved ones she lost. The movie heads into some very dark territory with her character, revealing that she is a pawn in a satanic cult’s ulterior plans, which have been placed upon her family for some time. And Toni Collette magnificently navigates the unraveling of her character, while still maintaining a grounded sense of who this woman is. In the final act of the film, we see the character of Annie fully possessed, and that’s where the character really becomes a nightmarish demon on screen. But even beforehand, Toni is terrifying in her role as she believably makes us see this character come apart mentally. Toni Collette’s performance has been seen by many as one of the all time best performances to never get an Oscar nomination, and people attribute this to the Academy’s bias against genre films, particularly horror. As my other picks on this list will show there are examples where there were horror performances too good for the Academy to ignore, but they did drop the ball by ignoring Toni here. The only thing that keeps it from being higher on this list is that the terrifying parts of her performance don’t come out until almost the very end, but what we do get is good enough to get her recognized here.

9.

BABY JANE HUDSON from WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE? (1962)

Played by Bette Davis

There was a weird movement in horror during the 1960’s that people have dubbed “Hag-sploitation.” It was a trend where horror filmmakers would create movies that centered around “scary old women” to give their stories a more gothic quality to them. In many cases, these “Hag horror” movies would give roles to aging actresses who were not getting any other work due to the way Hollywood devalued it’s female performers once they reached a certain age, and these roles were often seen as exploitational and indicative of the end of the road for these once beloved starlets. But this certainly wasn’t the case for Bette Davis. Even into her senior years, Bette was still at the peak of her talent, and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? showcases just how much she still had that spark of talent and was able to completely own even a sinister “hag’ role like that of Baby Jane Hudson. The film, interesting enough, is about an emotionally stunted former child actor who is clinging to past glory while taking out her aggression on her invalid sister played by Joan Crawford. What starts out as passive aggressive insults eventually devolves into psychological torture and then eventually acts of murder. And all the while, Baby Jane continues to slip deeper into insanity, which Bette Davis brilliantly displays in her performance. By the end of the movie, she has even devolved entirely into a childlike state of mind, and this is where she is at her creepiest, especially in the way that her concept of reality becomes more fractured, and it puts her sister in greater danger as she is witnessing that downfall firsthand. Davis’ performance certainly helps to raise Baby Jane above the otherwise bleakness of “Hag-sploitation.” You can tell this wasn’t just a desperate ploy for work; she was really invested in playing this character and it shows. It’s a masterful performance that even 60 years later still gives off creepy vibes and it was a benchmark role in horror filmmaking which led to a lot of imitations but none were ever able to deliver as powerfully as Bette did here.

RED from US (2019)

Played by Lupita Nyong’o

Sometimes the most terrifying kind of character is the one that looks exactly like us. That’s the angle that Jordan Peele went with for his sophomore film as a director. After tackling racial tension in his first film, Get Out (2017), he decided to look at class divisions in his follow-up, with a movie where affluent people on vacation are terrorized by their own doppelgangers, who seem to have come from underground laboratories and are tethered to our world while living in their hidden world under our feet; that is until they begin to rise up. And their leader is a terrifying character named Red; the only one of the doppelgangers capable of speaking, which she does in a restricted, damaged voice. Lupita Nyong’o plays the dual parts of Red and her “real world” counter part Adelaide, but it’s the former role where she really displays her acting talents. Red, with her doll face like expression and husky voice is a nightmarish presence in the movie and Lupita does not hold back in making her a memorable character. The fact that she’s the only one of the doppelgangers that displays any intelligence, as all of the others are feral by nature, makes her especially creepy. Lupita brings this almost alien quality to the character, like she is investigating her victims while at the same time seeking malicious ends. There is a twist revealed about the character, which does add another creepy layer to the character’s story, as well as to her relationship to Adelaide. Lupita and Jordan Peele could have taken a more conventional route with their take on a home invasion horror scenario, but with the character of Red and the other doppelgangers, they create this twisted examination of a society where the divide between the haves and the have nots could not be more clearly defined. And when we see our own selves presented back to us through the unnerving, almost frozen expression on Red’s doll like face, it clearly sends the message of the danger that lies beneath the surface of our class divides.

7.

LONGLEGS from LONGLEGS (2024)

Played by Nicholas Cage

This recent horror flick is already developing a reputation for being one of the creepiest in the last couple years, and part of that is due to an unexpectedly chilling performance from Nicholas Cage as the titular serial killer. The film itself is a bit like Fincher’s Se7en (1995), only with more supernatural elements mixed into it’s murder mystery. It’s a slow burn horror flick that takes place in an era where “Satanic Panic” was taking hold in pop culture, and the movie takes that theme to the extreme. What is clever about the movie is that the mystery is not about who is committing the murders, but how and why, and when we get our answers it’s not what you’d expect. Nicholas Cage is an actor known for going big with any role, and sometimes that can be a curse just as much as a blessing for some films. Here, his unpredictability as an actor actually works for the character. This Satan worshiping doll maker named Longlegs is deeply unsettling from the very first moment he appears on screen, and Cage’s willingness to take the character over the top adds just that extra bit of terrifying to the role. He speaks with this creepy Michael Jackson-like squeal of a voice and his face is pale and almost plastic like the dolls he creates. And Nicholas Cage’s penchant for unhinged outbursts really drive home the creep factor of the character, where every moment he spends on screen just gives you this spine-chilling feeling. It’s clear that Cage was really relishing this role, and the freedom it allowed him to just create something original. It’s one thing to create a cold, foreboding persona for a serial killer; it’s another to have him smiling and blowing kisses while singing “Happy Birthday” like Cage does as Longlegs. I have a feeling that this is going to be a character and a performance that people are going to be talking about for a while. For me, it is certainly the most the creepiest character I’ve seen in a long while in a movie, and proof that Nicholas Cage can be a great actor when his over the top instincts fit the right kind of role.

6.

NORMAN BATES from PSYCHO (1960)

Played by Anthony Perkins

While Cage’s Longlegs performance is fully displayed without any nuance to show us a different side of the character, Anthony Perkins on the other hand presents a very different approach to portraying a murderer. Norman Bates is one of the great misdirects ever achieved with a character in a horror film. When we first meet him, Norman seems like a mild-mannered road side motel manager who is devoted to caring for his mother. Perkins perfectly portrays this everyman aspect of Norman when we first meet him. He is harmless and soft-spoken and the character of Marion Crane (played by Janet Leigh) feels safe in his company. But as we listen to Norman speak a bit more during the fateful night that he and Marion meet, the mask slips ever so slightly, especially when they discuss topics like Norman’s mother and the “women” who come in between him and his devotion to “mother.” Alfred Hitchcock masterfully hides Norman Bates true nature throughout the film. Even when Marion is murdered in her hotel room, we quickly suspect that it’s Mrs. Bates and not Norman who did the deed, and we remain sympathetic to the mild-mannered man. But, as we move further into the plot, we learn that Norman is not what he seems, and by the end we find out that “mother” has been long gone and that Norman is the true killer. It’s the strength of Anthony Perkin’s performance that helps to keep the rouse up throughout the film, and it makes the ultimate reveal all the more satisfying as a result. Hitchcock’s Psycho, which itself was based on the notorious Ed Gein murders, changed the horror genre forever, and showed us that monsters are not just the creatures that spook us in the night. It showed that even the un-assuming boy next door could turn out to be a monster as well. And that hiding in plain sight portrayal of evil is what makes Norman Bates so terrifying. To drive that point home, Perkins delivers one of cinema’s greatest evil smiles in his final scene, with his mother’s decomposed skull briefly superimposed over his before the shot cuts away, showing us how the face of evil can sneakily appear so harmless at first.

5.

REGAN from THE EXORCIST (1973)

Played by Linda Blair; Voiced by Mercedes McCambridge

To be fair, the character of Regan herself is not the monster that terrifies in this film, but rather it’s the demon that has come to possess her. Even still, it’s a remarkable performance from Linda Blair to throw herself into the mayhem of her character’s possession like she does in William Friedkin’s ground-breaking horror flick. The deterioration of Regan throughout the film is terrifying to watch, and it’s incredibly shocking when we see this once sweet little girl causing self-mutilation and speaking profanities. As the demon takes hold even more, even her childish voice disappears and is replaced with the raspy, other-worldly voice of the demon. Veteran actress Mercedes McCambridge contributed her own husky voice to the role of the demon and it’s a remarkable vocal performance, making the demon sound unlike anything of this world. Mercedes probably relished saying the shocking lines that the demon utters in the film, like “Your mother s**** c**** in Hell,” because not only were they barrier pushing for their time, but there was the added shocking factor that those words were coming out of a child; albeit a possessed one. A lot of credit is due to Linda Blair perfectly lip-synching to the demonic voice as well. For a movie like The Exorcist to work, the audience needed to buy into the belief that the demonic possession they were watching felt real. The results from Linda and Mercedes performances not only made it feel real, they made Regan’s possession feel like evil literally captured on the screen before us. It had to be daunting for an actress Linda’s age, and there are stories of Freidkin’s set being a bit hazardous at times, but she displayed a command of the role that you wouldn’t expect a young actor to have, especially when their job is to scare the daylights out of the audience. And what her performance ended up giving us is one of cinema’s most terrifying performances ever.

4.

JACK TORRENCE from THE SHINING (1980)

Played by Jack Nicholson

Much like Toni Collette’s descent into madness in Hereditary, we see the same change in character from Jack Torrence in The Shining, only the fall is much, much bigger in this acclaimed adaptation of the Stephen King novel. Jack Nicholson is another actor who likes to go big in his roles, and Stanley Kubrick very much let him go big here. What’s great about Nicholson’s performance is that the build to insanity isn’t so much gradual as it is taking things one step further after starting in an already heightened place. Jack Torrence is first introduced as even-keeled in the beginning, but the wheels begin coming off not too far from that, especially as isolation begins to take it’s toll on the character’s psyche. Nicholson’s performance is quintessentially him, with himself ratcheting his own persona beyond it’s limits. By the time he reaches his full murderous state, Nicholson’s performance becomes truly a nightmarish presence. We get our first taste of the worst of his character during the “All work and No play” scene when he confronts his wife Wendy (played brilliantly by the late great Shelly Duvall), and it’s effectively creepy how he is able to scare us while also doing so with a smile. And the of course there’s the climatic chase through the Overlook Hotel where the ax-wielding Jack pokes his face through the door and screams out “here’s Johnny.” It makes it all the scarier that he’s playing around with his victims while hunting them down in a murderous rage. By the end of the film, there is zero subtlety left in Nicholson’s performance, but that really is what makes him so effectively terrifying in that final stretch; just the unhinged nature of his character at that point. That’s the scariest kind of evil, when the person you loved no longer feels anything but blinding rage, and seems to enjoy using their power to terrorize you. The story leads us to believe that the Overlook turned Jack towards evil, but the movie and Jack Nicholson’s performance also indicates to us that Jack Torrence didn’t need that much of a push to go off the deep end, and they show that to us in quite a spectacular way.

3.

ANNIE WILKES from MISERY (1990)

Played by Kathy Bates

Staying with Stephen King for one more film, we find an example of a horror film performance so good that the Academy was wise not to ignore it. Kathy Bates star making turn as Annie Wilkes in Misery did earn her a much deserved Oscar for Best Actress, and it’s a role that managed to display incredible acting chops on the part of Bates as well as be terrifying and not watered down at all in order to fit the Academy’s standards. The character of Annie Wilkes seems to be an externalized expression of fear on the part of Stephen King, as she is the epitome of toxic fandom in the extreme. What is interesting about Bates performance is that she appears warm and matronly at first, but only a couple scenes later we see her turn into a rage monster that snaps over the most minor of infractions. There is clearly something going on with the psyche of Annie Wilkes, but Kathy Bates is wise to not soften her character too much. Annie is a monster to be sure, and the strength of Bates performance is in showing the full range of dangerous extremes that Annie can go to at any time. Perhaps the best example of Kathy Bates’ brilliance in her performance is the most famous scene in the movie when Annie has the writer Paul Sheldon (a great James Caan) tied to the bed, where she plans to hobble him by purposely breaking his feet with a sledgehammer. The best part of that scene is just how soothing and calm Annie is, right before she does the shockingly violent act. It makes her all the terrifying as a result; how disassociated she is from the horror she is inflicting. Kathy Bates certainly goes over the top too with the character through some rage filled explosions, but it’s those quieter moments of madness that really give us the chilling effect. Creating a character like her must have been cathartic for Stephen King as he probably encountered one too many fans who displayed a little bit of obsessiveness themselves; though not to the extreme that we see with Annie Wilkes. I think it’s that familiarity with the character (her obsessiveness and rigid conformity) that makes her one of cinema’s most terrifying characters; evil personified with sugar-coated sweetness.

2.

COUNT ORLOCK from NOSFERATU (1922)

Played by Max Schreck

It’s amazing that one of the earliest horror movies still manages to hold up over a century later, and the same goes for the terrifying performance at it’s center. Director F.W. Murnau was unable to secure the rights to the novel Dracula from the Bram Stoker estate, so he crafted a vampire story of his own that was still fairly close to the original. Nosferatu became the first ever vampire movie, and much of the rules of horror cinema stems directly from this ground breaking film. The vampire at it’s center, Count Orlock, is vividly brought to life by the unforgettable Max Schreck. The lanky build and statuesque height of the actor creates this image of an otherworldly creature, and it’s a nightmarish image that still sticks with audiences today. It’s especially terrifying when we see him standing at the end of a dark corridor in the middle of the night, and even more terrifying when he later stands in the frame of a doorway about to enter the room to feed on his prey. Murnau effectively creates this sense of terror without having Schreck do much action at all. It’s all about how Count Orlock’s mere presence creates this foreboding atmosphere in every scene that he’s in. Murnau also makes brilliant use of shadows to invoke the vampire’s presence even when he’s not physically on screen. The performance that Schreck gave was so convincing that speculation rose that he was an actual vampire, which became the basis for a behind the scenes biopic called Shadow of the Vampire (2000), where he was played by Willem Dafoe. We have since seen Dracula brought to the screen many times, including brilliantly the first time by Bela Lugosi, but even in all his many versions, I don’t think there has been a Dracula that has terrified audiences the same way as Count Orlock. For a 100 year old movie to still have the ability to terrify it’s audience is a real testament to the effectiveness of Schreck’s performance, and we owe every portrayal of vampires in cinema to the high bar that he set with his spine-chilling on screen portrayal.

1.

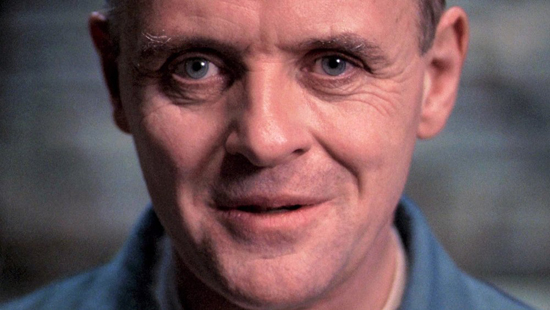

HANNIBAL LECTER from THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS (1991)

Played by Anthony Hopkins

For all the critics who look down on acting found in horror movies, it should be noted that what many regard as one of the greatest performances ever committed to celluloid did in fact come from a horror movie. Anthony Hopkin’s became a cinema icon with his portrayal of the hyper intellectual cannibal behind bars in this Oscar winning Jonathan Demme film. It’s interesting to note that Dr. Hannibal Lecter, for as terrifying as he is, is not the main antagonist of the movie, nor is he an obstacle for the hero Clarice Starling (an equally brilliant Jodie Foster) as he spends the movie as her ally in her search for the “Buffalo Bill” serial killer. But make no mistake, Hannibal is still a monster and the movie does such an effective job making every moment in his presence the stuff of nightmares. The brilliance of Jonathan Demme’s direction is that he puts the camera right in the faces of his actors. Anthony Hopkins delivers his chilling performance while looking right down the barrel of the camera, making his presence feel all the more invasive. It’s also unsettling that we rarely see him blinking as well. With Hannibal Lecter, it’s not about what he does that terrifies, but the way he casts a pallor of foreboding over a scene with his methodical way of talking and the stillness of his movements. He’s like a demon that you feel waiting for you in the darkness, only he’s here fully lit and we are unable to escape his piercing gaze. The movie still shows us how dangerous he can be with the prison break scene, where he goes on a bloody spree of violence after spending the whole rest of the movie behind bars. Hopkins’ Oscar win for the role was a no-brainer, and he would continue to bring the character back to the screen in subsequent sequels and prequels. But it’s here in The Silence of the Lambs that we see him at his most terrifying. No other performance on screen makes you feel like the villain is piercing right into your soul and haunting you without doing much at all. It’s that psychological terror that makes Anthony Hopkin’s performance as Hannibal Lecter the most terrifying ever put on screen. It raised the bar in portraying terror on screen, and showed that even horror could raise the bar high for all cinematic acting in general.

So, there you have my choices for the most terrifying performances ever in movies. Some are more obvious than others, but what I find interesting is how well older horror films have held up over the years in showcasing great performances that still can terrify audiences today. Anthony Perkin’s portrayal as Norman Bates is still a brilliant bait and switch that can still shock audiences, as well as Bette Davis giving us one of the most vivid portrayals of madness on screen as Baby Jane Hudson. And then of course there’s Max Schreck whose chilling portrayal of a vampire is still the gold standard for the sub-genre 100 years after the fact. Also the fact that both Anthony Hopkins and Kathy Bates have won Academy Awards for their unapologetic horror movie performances shows that the genre is just as capable of presenting quality acting as any other genre out there. Recent examples like Toni Collette in Hereditary and Lupita Nyong’o show that great actors can still deliver their best work in scary movies, and I feel like Nicholas Cage’s recent work in Longlegs will also stand the test of time and be regarded as one of the best in the genre. What is great about all the performances on this list is that they displayed great acting while also accomplishing the goal of being scary. It shows that you don’t have to water down a terrifying performance in order to get critical praise. Are there bad performances in horror movies? Sure, but no more so than any other genre. The low budget stigma surrounding horror movies seems to have also extended to the perceptions of the performances given in them as well, but that seems to have changed in the last few years as more and more A-listers are looking to spread their wings in the horror genre. While it can sometimes be risky, horror movies tend to do better when they allow their actors to abandon their guardrails and just let loose, and that seems to be what is appealing to actors more and more these days. There is a freeing aspect to what the horror genre can do for actors who just want to do something wild and weird every now and then. And as this list has shown, some of those unhinged performances turn into some of our favorite performances. That’s the blessing of horror in Hollywood; it gives it’s talent the chance to be weird, wacky and unbound in a genre where all that is valued. And as we’ve seen, the best actors alive have been the ones who have scared us the most.