Since starting this retrospective series examining the many great directors that have contributed to the history of cinema, I’ve come to realize that there is a certain kind of filmmaker that I have yet to spotlight here; mainly women. It’s no secret that Hollywood has had a fairly lackluster record in recognizing women as filmmakers within their industry. Thus far at the Academy Awards, in all of it’s 94 year history, only two Best Director honors have been given out to women, and the second one was only in the last year. That being said, there have been women directing films ever since the early days of cinema. In Hollywood, there have been often unheralded names like Dorothy Arzner and Ida Lupino who stood out as part of the Golden Age, and in later years, there were filmmakers such as Elaine May and Penny Marshall who not only managed to direct studio films, but they also managed to make them big hits as well. Internationally, there were also standouts like Lina Wertmueller and Agnes Varda who won acclaim for their groundbreaking work. But, for most of those years, a lot of the women working in cinema were not able to stay competitive with their male counterparts. This, thankfully, is a trend that’s now starting to crest and become a thing of the past, as there are far more movies, both independent and studio made, that are helmed by women. Half of the comic book super hero movies from last year in fact were made by women: Patty Jenkins (Wonder Woman 1984), Cate Shortland (Black Widow) and Chloe Zhao (Eternals). But, if there was a certain woman director that has stood out as one of the most groundbreaking in the last few decades, and whose films have become uniquely identified as a distinctive body of work, it would be Kiwi filmmaker Jane Campion.

Jane Campion was born in Wellington, New Zealand in 1954 and before she pursued a career in film, she originally studied to become an artist. She enrolled at the Sydney College of the Arts in Australia and found herself drawn to the School of Film and Television. There she found her true calling, and she immediately left a mark as a unique cinematic voice. Her student film, Peel (1982), would go on to win the Short Film Palm d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1986, which is pretty remarkable for a first time director. She would continue to direct further shorts and films for Australian television, before making her feature debut with Sweetie (1989). That movie with it’s idiosyncratic look at female sexuality and social interactions would establish many of the themes that she would continue to explore throughout her career. She would release another introspective look at female identity in her follow-up, An Angel at My Table (1990), but that was only a warm-up to the movie that would cement her as a filmmaker to be reckoned with. In 1993, Jane released her ambitious period piece The Piano to wide acclaim. With it, she became the first woman director to win the feature Palm d’Or at the Cannes Festival, and she would further go on to win an Academy Award for her Original Screenplay. She also became only the second woman in history to be nominated for the Best Director honor, which she ended up losing to Steven Spielberg for Schindler’s List (1993). In the years that followed, she would build upon the success of The Piano to create more unique and lavishly crafted movies about the lives of women, including Portrait of a Lady (1996), Holy Smoke (1998), In the Cut (2003) and Bright Star (2009). She then suddenly left the directors chair completely, citing her growing frustration with Hollywood and the growing capitalistic nature of the industry in general. During the 2010’s, her sole project was co-creating the short-lived but acclaimed series Top of the Lake. And then, suddenly, it was announced that Jane was suddenly making a return to film with her new revisionist Western entitled The Power of the Dog (2021) thanks to Netflix; a film that again has set her up historically as the first woman nominated for Best Director twice, and this time with a better shot at coming away victorious. Needless to say, she is a very interesting filmmaker to examine and what follows are some of the cinematic traits that have defined her body of work thus far.

1.

LUSH PALETTES AND NON-SYMMETRICAL FRAMING

If there is something that really stands out in Jane Campion’s oeuvre, it’s her cinematic eye. You can really see the art school influence in her work, as she treats the lens of the camera like a brush on a canvas. What is interesting is the way she frames her scenes, often choosing to have her action either outside of center frame or even sometimes strangely cut off by the edges. This is especially true with her earlier films like Sweetie and An Angel at My Table, where she plays around with perspective in interesting ways that in many ways is reflective of the fractured nature of her characters. In many ways, she uses things like her framing and color palette to reflect the emotional state of her characters, with an intentional eye towards making things disorienting for the audience as well. Campion is not afraid of testing the sensibilities of her audience, and she certainly has the talent and natural vision to pull that off. What is also interesting is how she often uses color to reflect the emotional state of her characters. Her upbringing in a picturesque country like New Zealand no doubt was influential in giving her a visual perspective, but what I find interesting is the way she explores colors to the extremes. There’s a very interesting mix of bright and muted colors in her films. Some of her earlier work in movies like Sweetie show her pushing the full spectrum of color visually. But in movies like The Piano, she also spotlights the lack of color as a key visual element in her story, as much of that film takes place in cold, overcast atmosphere. Her more recent The Power of the Dog also displays interesting usage of color themes in the story, especially against the barren dirt brown setting of her story. Overall, these two elements have shown her to be a powerful visual storyteller, and it’s nice to see that it has remained as uncompromising as it was in the earliest part of her career.

2.

THE NATURAL WORLD

As a reflection of her native New Zealand surroundings, Jane Campion has used nature as an important thematic element in her movies as well. Her period films in particular have a strong sense of openness of the larger world and how it overwhelms the inhabitants of her stories. Two films in particular, The Piano and The Power of the Dog feature many unforgettable visuals of the characters being dwarfed by their wide open surroundings. Remarkably, in The Power of the Dog, Campion managed to successfully have the countryside of the South Island of New Zealand play the role of rural Montana, and you would be hard pressed to know the difference. Not only that, she pulls the camera way back in vista shots that really capture the expanse of the film’s setting wit epic grandeur. She likewise accomplished the same thing with the beachfront scenes in The Piano, where her stars, Holly Hunter and Anna Paquin, are practically overwhelmed by the expanse of their surroundings. Campion has only ventured away from her homeland rarely as a filmmaker, but even when she does, she brings the same kind of sense of the surroundings informing the emotional state of her characters throughout the films. For Holy Smoke, it’s the lush exoticism of India, for In the Cut, it’s the oppressive modernity of New York City, and for Portrait of a Lady, it’s the rigid conformity of Victorian England. For most of her filmography, she has used the outdoors as a key part of her storytelling, and often it’s in the wilds of nature that we see her characters discover the most about their own identity. This is something that has carried through most of her work in film, and sets her apart as a visual storyteller. Every shot of wide expanses reveals something about the characters that inhabit it; and often it’s a catalyst for her characters to evolve, especially if being out in the wilds of nature is an entirely new experience for them in the story.

3.

UNNERVING MUSICAL EXPRESSION

One thing that Jane Campion also likes to accomplish in her stories is catch her audience off guard and even leave them uneasy with some rather out of left field choices. One way she does that is through music. Sometimes music becomes a way she allows her characters to express their buried emotions, but she even uses this in uncomfortably challenging ways. One of the most unusual uses of music she has made in any of her films can be found in an early short movie she made called A Girl’s Own Story (1984). In that movie, we watch this gritty story of awkward sexual awakening between teenage girls. And then, all of a sudden at the very tail end of the film, the characters break down the fourth wall and we are suddenly launched into a music video. It’s really bizarre, and yet thematically in line with Jane Campion’s sensibilities. She further explores the idea of music as an expressive element far more overtly in the film The Piano. Naturally, with a movie named after a musical instrument, this theme would be a part of the narrative, and indeed the story centers around a mute woman (played by Holly Hunter) who communicates her emotional state through the playing of the piano. The piano becomes this deeply connected element in her story, and it even plays a part in determining her fate by the end of the film. There’s also an unforgettable use of music in The Power of the Dog, where a musical duet between two opposing characters becomes this unnerving act of terror. Benedict Cumberbatch’s sadistic and hyper masculine cowboy uses a melody throughout the film to psychologically torture his new sister-in-law (played by Kirsten Dunst), bringing yet another challenging usage of the theme by Campion to put her audience in an unsettled state. Though her films are scored by some great composers, like Michael Nyman and Johnny Greenwood, it’s these moments of diegetic music within the story that take on unnerving and out-of-left-field thematic elements, that become unforgettable parts of her movies overall.

4.

UNREQUITED PASSION

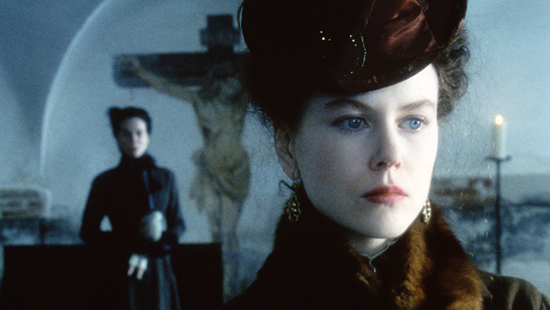

One theme that is also very much central to Jane Campion’s body of work is the exploration of sexuality; particularly female sexuality. It’s something that she has explored in most of her films, even going back to her early shorts. Her feature debut includes sibling rivalry over the competition of gaining the attention of the same desired man. In The Piano, her female protagonist falls into a passionate affair with a plantation worker (played by Harvey Keitel) after becoming emotionally resigned from her unhappy marriage to an abusive husband (played by Sam Neill). The theme is explored even more overtly in Portrait of a Lady, where Nicole Kidman’s heiress ends up entrapped in a loveless marriage that denies her the autonomy and freedom to be the woman she desires to be, again because of cruel and possessive husband (this time played by John Malkovich). Her one film that takes a more positive outlook on love is the tragic love story fond in Bright Star, which still tells the story from the perspective of the woman in the story; in this case poet Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish) who becomes the muse and love of legendary writer John Keats (Ben Whishaw). It’s interesting that with her new film, The Power of the Dog, Jane Campion actually breaks from the norm and instead examines male sexuality instead, albeit still keeping with the theme of unrequited desire at it’s heart. In that movie, we learn that Benedict Cumberbatch’s Phil Burbank uses his hyper masculinity as a mask to shield his true queer sexuality, and how the resentment built up from having to always keep that hidden makes him menacing to those around him, especially when he encounters his new nephew (Kodi Smit-McPhee) who exhibits feminine qualities without shame. Jane Campion isn’t afraid to explore the darker side of sexual awakening, and that has made her films all that much more interesting. She knows the complexity of sexuality is best explored when her characters have to struggle to discover what it means for themselves.

5.

FEMININITY AT A CROSSROADS

There are a lot of women filmmakers out there that don’t want to be thought of as directors of “women pictures,” and you’ll often see many try hard to define themselves as capable of tackling any genre regardless of what’s expected of their gender. Many definitely excel at that to. But Jane Campion will definitely say that she makes pictures for women about women and proudly so. What helps her to stand out is that she tackles female issues within her stories, but doesn’t play it safe as well. She makes an effort to make sure that her female characters are not 100% pure or morally in the right. Her female protagonists can often for the most part be more flawed than their male counterparts, and that in turn helps to make them even more interesting. The two sisters at the center of Sweetie are petty and selfish, but in a way that makes them endearing to the audience. Holly Hunter’s Ada in The Piano gives in to adultery, but only after her husband has denied her any happiness in her new home. And Kirsten Dunst’s Rose in The Power of the Dog is a raging alcoholic, but as we see it’s in response to being oppressed by her sadistic brother-in-law. For all these women, they have to continually assert their feminine dignity in both opposition to the men that dominate their lives, but also the faults of their own character. It’s refreshing that Jane Campion is un-compromising in showing the complexities of her characters. Her stories really do shed a necessary light on the real lives that women lead, and there is a lot of honesty in showing how character morality is never so easily defined. It’s especially rewarding to see her explore the issues that she does in movies that often pander to certain audiences; the Western, the period romance, and the coming-of-age tale. That’s why her female characters are often the most interesting in all of cinema.

Jane Campion is a pioneer filmmaker with regards to how she has been a role model for up-and-coming female directors from around the world. What makes her especially special is the fact that she has refused to comply with the standards of the industry. She is a filmmaker who stands by her vision, even if that puts her at odds with the rest of the industry. You’ve got to admire a filmmaker who decides to walk away in response to the unfair standards that the industry places on women who aspire to work in the same fields that have often been dominated by men. Thankfully, she also has managed to find a way to make a return. She must have been drawn to Netflix’s release strategy, which puts less pressure on a movie to perform strongly at the box office. The Power of the Dog is a movie that likely would’ve been enriched by a big screen presentation, with Campion using her keen cinematic eye to capture some beautiful vista shots, but by virtue of being on a platform like Netflix, her film is likely going to find a bigger audience than it would’ve in a theater and that probably is what appealed to her. She was not under any pressure to compromise her vision and make the movie that she wanted to make. It’s a deal that worked out for both parties; Jane Campion gets to make a triumphant return to feature films and Netflix has a surefire Oscar contender. Campion’s history making second nomination is a milestone long overdue, and hopefully she can translate it into a Best Director win, which will solidify her legacy even more. Regardless, she is an artist of unique vision who dares to tell stories that most filmmakers wouldn’t, and does so with a very strong visual sense as well. She comes from a long line of historic women who have worked behind the camera, and has been the inspiration for many more that have followed after. Hopefully, with the success of The Power of the Dog this last year, we are seeing the beginnings of an exciting second act for Ms. Campion.