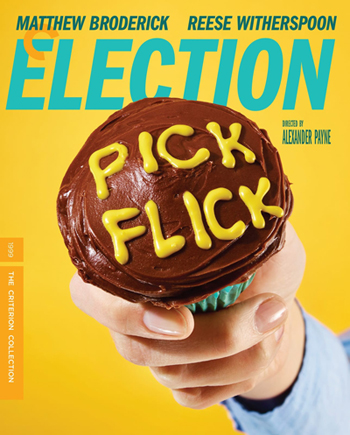

We are mere days away from that time again, when we must do our duty as citizens and vote for who will lead our country for the next few years. It’s a day that we are either eagerly awaiting, or more likely dreading. But, nevertheless it is an essential function of a healthy democracy, where every voice matters. Much of the political discourse in our nation, for better and worse, is influenced greatly by our culture and Hollywood has contributed it’s fair share of political movies over the years. A few of those films have become special enough to be recognized by the Criterion Collection, and they span a wide variety of issues. There are political thrillers from the likes of director Costa-Gavras, namely Z (1969, Spine #491) and Missing (1982, #449). There’s also Watergate era paranoia thrillers like The Parallax View (1974, #1064). Political documentaries also are represented in the collection, like Harlan County U.S.A (1976, #334) and Hearts and Minds (1974, #156). But perhaps the most politically charged film that are found in the Criterion Collection are the political satires. Some of the most hard hitting ones include Robert Altman’s 11-part mini-series Tanner ’88 (1988, #258), where it skewers the American political machine by running a fake candidate in a real election. There is also the chillingly prophetic film A Face in the Crowd (1957, #970) from Elia Kazan, where a loud mouth entertainer is propped up to run for office and over the course of time becomes a dangerous demagogue; a savage critique of the toxic relationship between media and politics that feels eerily too close to reality today. But perhaps the one of the most interesting political satires that has made it into the Criterion Collection is a little film about a high school student body election that over the course of the film reveals itself to be a microcosm of the American way of politics in it’s entirety. That movie would be Alexander Payne’s breakthrough second feature simply titled Election (1999, #904)

Alexander Payne beforehand was no stranger to tackling politics in his movies before Election. His first feature, Citizen Ruth (1996), satirized the debate around abortion in America during the 1990’s. A movie like Election seemed like a logical next step. But it is interesting that ever since, Payne has largely avoided overt political stories in the rest of his body of work. Through the following two decades he was more concerned with human stories such as About Schmidt (2002), Sideways (2004), The Descendants (2011), Nebraska (2013) and most recently with The Holdovers (2023). Really, the only movie in that time where he returned to making a political satire, it was the movie Downsizing (2017) which many people agree is his least successful film. Election does fit well within his larger body of work mainly because it is a film about characters more than it is about any political agenda. For his film, Alexander Payne and his frequent writing partner Jim Taylor created characters that reveal themselves to be familiar archetypes of the kind that you see pop up in any contentious political campaign. By keeping the scope of his setting small, Payne helps to draw more attention to the stakes of this small scale election and how it pertains to the characters in his story. While the stakes are small, the way these characters deal with their own scheming and manipulation in order to seek victory in this election reveals an interesting concept that has a far more reaching conclusion than you would think from the start. All of the pettiness and backstabbing we see in politics today really isn’t that far removed from the way we behaved when we were in high school. Politics has grown increasingly juvenile over the years, with elections becoming more of a clash of personalities than a clash of ideas. The fact that social media and the ability to meme is a function of campaigns today is just another sign of how spot on Alexander Payne’s satirical look at campaigning was. It should have been a wake-up call, but instead it was sadly ahead of it’s time.

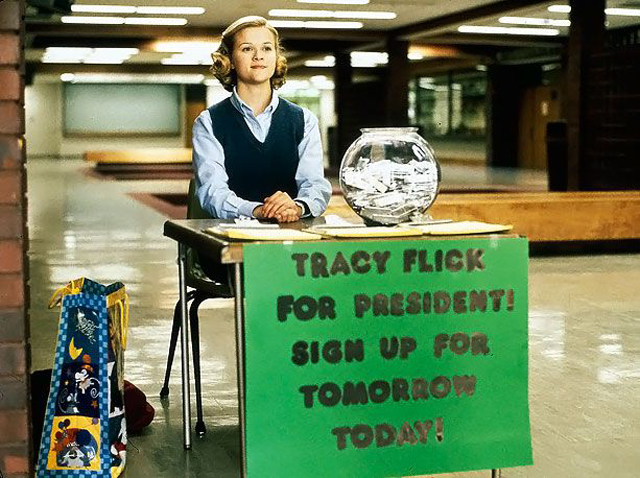

Set in Alexander Payne’s hometown of Omaha, Nebraska (as most of his films are), the movie follows the student body election of Carver High. Currently, the overly ambitious and over-achieving Tracy Flick (Reese Witherspoon) is running un-opposed for student body president, but even despite of that, she is aggressively campaigning in a way that even Beltway insiders would find over the top. Her election seems like a foregone conclusion, until History and Civics teacher Jim McAllister (Matthew Broderick) decides to shake the campaign up. McAllister has grown to dislike Ms. Flick after she got herself involved in a sexual relationship with the geometry teacher who was also Jim’s best friend. Though he agreed that his friend Dave should have been fired for the inappropriate relationship he had with a student, Jim is also upset that Tracy did not face any consequences herself. As a way of trying to make her pay for her misdeed, he convinces dim-witted star football player Paul Metzler (Chris Klein) to run for class president as well. While completely lacking in any of the same knowledge needed to run student government like Tracy has, Paul nevertheless gains support from the student body by virtue of his simple charisma. Tracy is outraged that the clearly unqualified Paul is just coasting through his campaign while she is working hard and getting nothing in return. To make things even more complicated, Paul’s lesbian sister Tammy (Jessica Campbell) decides to enter the race herself as a spoiler third party candidate, running on a position of ending student government in general. When the day of the election comes, McAllister finds that Tracy has won by only a single vote. Not wanting to see her succeed, he hides the last couple votes she would need for victory, and hands the election to Paul. However, McAllister’s dirty deed is discovered and he loses his job for the election interference. Tracy gets the student body president position she always wanted, but it comes at the cost of alienating her from half of the student body. Despite the victories gained, the movie shows us that the fight itself is not without cost.

It’s hard not to watch the movie today and not see the parallels with American politics today. Even when it first was released, many people were shocked by how much the film predicted what would happen in the presidential election a year later. Before the 2016 and 2020 elections became the messy situations that we have recently endured, the 2000 election between George W. Bush and Al Gore was at the time the most controversial in American history. Just like the race seen in Election, it was a contest between an ill-informed but folksy son of privilege versus an intelligent but socially awkward career politician and the race did literally come down to just a couple of votes out of millions cast. When Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor wrote their screenplay, they probably thought that their premise would be far too ridiculous to ever come true, but as we’ve sadly learned about American politics, reality has become stranger than fiction. Where the movie Election really nails the satire is in showing how politics is a very petty game of one-upsmanship. Tracy Flick may have the stamina and knowledge to do student government right, but we also see that it’s a desperate cry out for attention for her. In a way, the movie does present it as a positive point about her character, since she is shown to not have a lot of wealth and influence behind her so she is entirely self-reliant. But she is also shrill and dismissive of others, believing that she alone is capable of doing the job of student president. Meanwhile, Jim McAllister is a petty person for putting his own resentment of Tracy before the needs of the student government. In many way, an audience reading of the film can say a lot about us as a nation when it comes to deciding who’s in the right and the wrong. Some may see McAllister as the hero for stopping someone as power hungry as Tracy Flick from getting what she wants. Others may view him as the villain for deliberately disenfranchising voters for his own petty ends. In the end, the thing that I think Alexander Payne is trying to say is that everyone in this film is a terrible person in their own way, and that that’s just politics has become over time; picking the least awful person for the job.

But what definitely wasn’t awful was the craft that was put into this movie. Alexander Payne’s become a master at capturing what you would call mid-American ambiance in his movies. Hailing from Nebraska, he has a fondness for fly-over country simplicity and Election definitely feels at home in that vision as well. Even while the perspective on the American political process is examined with a lot of cynicism in the movie, the perspective on the people and the place where they live is not. Payne’s very humanistic outlook for the characters in his movies very much helps this movie from becoming too sour of a portrayal of political machinations. It also helps that he cast the right people to play the parts in the film too. Reese Witherspoon is just note perfect as the efficient to a fault Tracy Flick. Before Election, Reese had been one of the go to actresses at the time to play deeply troubled teenage girls, with breakout roles in Pleasantville (1998) and Cruel Intentions (1999). Playing the buttoned-up and over-achieving Tracy was a bit of a departure for her, but not something that she wasn’t capable of pulling off. It also gave her a place to shine her credentials in comedy, something that she would carry with her to box office success in 2001’s Legally Blonde soon after. Opposite her is a wonderfully sleazy performance from Matthew Broderick as Jim McAllister. He does a great job of playing this character as pathetically petty while at the same time giving him a sense of relatability that helps to prevent him from being two one-dimensionally evil. Also, Chris Klein makes for a perfect dim-witted jock in the role of Paul Metzler. He himself wasn’t too far removed from appearing in the sex comedy American Pie (1999), so he probably knew exactly the kind of charming empty vessel that the movie needed to get the political metaphor across. Indeed, in lesser capable hands, a political satire like this would have gotten muddled with too much overt symbolism, and with Payne keeping it grounded in his simple Nebraskan style, he was able to create a more provocative film as a whole.

For this film’s release within the Criterion label, the film underwent a new 4K digital transfer, approved by Alexander Payne himself. Sadly, the film has only been put out by Criterion solely on Blu-ray and DVD, with no word yet of a 4K release in the future. So while the movie is playing on these lower resolution presentations, it should be said that the movie does indeed still look good. For a movie reaching it’s 25th Anniversary it still holds up pretty well. Cinematographer James Glennon’s work shines through in the new transfer, with the naturalistic colors really getting a great treatment in the restoration. The digital transfer was sourced from the original negatives, so it’s understandable that it would look pretty immaculate. One can only imagine what a 4K disc version of this movie would look like. The movie also features a new DTS 5.1 surround mix based on the original film’s sound mix. Election is not a particularly dynamic sound experience, as like most Payne films it’s a fairly quiet movie from beginning to end. There are some bright spots that do give you a full aural experience, like the scene where Tracy has a meltdown and starts ripping up campaign posters in the high school hallway. The film’s soundtrack, which features quite a few country songs, also benefits from Criterion’s very clean and strong sound mix for this release. I do wish that Criterion gives this movie a proper 4K UHD release in the future, but it’s also not a movie that’s meant to be a showcase for picture and sound. It’s treated respectfully in it’s presentation on Blu-ray and should look and sound great on most home entertainment set-ups.

Criterion of course delivers a bountiful collection of extra features for this release. Some are old, taken from Paramount Pictures’ previous DVD and Blu-ray releases of the film, as well as new ones from Criterion themselves. The most prominent feature is an Audio Commentary track from Alexander Payne himself, recorded in 1999 for the original DVD release of the film. The commentary is informative, with Payne going into detail about why he made the movie, it’s not so subtle political message, and a variety of other topics. Of the new bonus features, the most substantial is a brand new interview with Reese Witherspoon herself. It’s interesting to see her looking back on the film with the perspective of several years being removed from it. She talks about how the film changed the course of her career, what she thinks about the character of Tracy and how the film has aged with regards to it’s reflecting of real world politics since it’s release. Another interesting inclusion in the bonus features is the inclusion of Alexander Payne’s student thesis film from his studying at UCLA’s film school, titled The Passion of Martin (1990). It’s a fascinating inclusion on this disc, giving us a look at the origins of Alexander Payne as a filmmaker, seeing him working out what kind of films he wanted to make. Also on the Criterion disc is a 2016 documentary called Trulnside: Election, which features on-set footage of the making of the movie and interviews with the cast and crew. There’s also a very fun inclusion of the local Omaha news reports that chronicled the film’s production, which I guess was a big deal for the citizens of Omaha at the time as many films typically are not made there. Lastly there is an original theatrical film trailer, which is a standard feature on most Criterion Collection releases. Overall, Criterion compliments the film with some very nice bonus features about the film’s making, as well as some interesting bonuses that give some perspective on the film’s impact over time.

With a lot of political satires, there is a danger of being too on the nose about your message, or too mean-spirited about the people you are trying to mock. Alexander Payne manages to reach the right tone with Election. His mockery is more geared toward the process of American politics and less so of the people. Sure, characters like Tracy Flick and Jim McCallister are flawed and fueled by jealousy and insecurity, which is a terrible mix in the realm of politics, but Payne allows us to understand that all of his characters are human beings as well; each one broken in their own way and trying to survive in the best way they can while trying to shield the world from their inadequacies. The characters in Election feel all too real, and that’s what helps to get the point of the film across. Our political reality has just become increasingly more absurd over time, with social media fanning the flames even more. And even though Election came at a time long before social media, and really only just a couple years into the era of the Internet revolution, it’s metaphor still resonates. Just this year alone, we are worrying about bad actors interfering with the counting of votes in order to get their preferred candidate into office, and throwing democracy out the window as a result. The moment in the movie of Jim McAllister tossing those few votes into the trash can doesn’t seem all that different from reality anymore. While Payne’s film remains hopeful about the people trying to strive for what’s best in the end, sadly it’s the reality of petty grievances getting in the way that makes Election feel all too prophetic in the end. The one thing he left out is how bad the demagoguery would get in the world of politics we live in now. The saddest part of the film is how politics ends up destroying people in the end. A character like Tracy Flick feels very familiar to us. She has to perform even harder to achieve her goals by virtue of being a woman, because men are given more privilege in the world of politics. So many men of privilege like Paul Metzger seem to have the keys to power given over to them without much struggle, as they can make all the mistakes they want and still succeed, while even a simple flaw can destroy a woman seeking the same goal. Hopefully we’ll move past that obstacle soon in the world of politics (fingers crossed for this week’s election), but as movies like Election have shown us, politics is a game where there is no clean victory. Another solid entry from Criterion that in addition to a lot of other great films about politics only gets more relevant with time.

Criterion Cellection – Election (1999)