We’ve all seen it happen before. Something that you cherished in your youth will end up loosing value as you get older. Trends change and so do we. Whether it was some toy we played with or some book we read, our tastes in entertainment evolve over time as we begin to mature and explore new things, and movies are no different. Perhaps more than most other forms of entertainment, cinema is more prone to the ravages of time and often we see perhaps one or more films become lost to time because of how poorly it has aged. Sometimes, even entire genres are swallowed up by the passage of time, and are only revived by completely unexpected factors. But it’s only because most films want to reach the strongest possible audience in their specific time, so these movies end up reflecting the times in which they were made, making their stories more relatable to that contemporary audience. It’s not always the case though, and sometimes we find movies that can be so easily defined by the era they were made in. Movies can end up being timeless given the right kind of story or the right kind of vision. And these are the films that can still entertain decades later, while the films that are dated end up becoming curiosities of their era. What’s interesting about this is that by looking at all the films that have dated poorly over the years, you can actually learn something of the values of the culture at the time; whether it was the whitewash optimism of the 1950’s, the turbulent psychedelia of the 60’s, the grunginess of the 70’s, the excess of the 80’s, or even the naivete of the 90’s. Every era has it’s mark and the more closely the movies exploited these time periods, the more likely they were going to be left behind when it was over. Thus, do we find the movies that truly are timeless as they live on in our memories long after all the others are forgotten.

Trends tend to be the motivating factor behind the movies that get left behind by the passage of time. Mostly seen in low budget movies from any era, popular fads in the pop culture will end up motivating production studios to quickly cobble together movies geared towards exploiting the fad with little thought put into it. That’s why you see a lot of movies that give us a glimpse of a long forgotten pop cultural benchmark as well as feature some of the most paper thin plots and terrible acting that anyone has ever seen. A great example of this was the “beach blanket” movies of the 1960’s, which featured the likes of Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon in the cast and were little else than excuses to film people hanging out on the beach and singing pop tunes of the period, which I guess was a thing 50 years ago. The beach movies of the 60’s may have hit their mark in their time, but those movies quickly went away once audiences’ tastes began to change, and the psychedelic era began to be exploited by the studios. Every era follows this same pattern, as new pop culture trends reflect back in the movies being made. Even trends that did evolve and improve over time are given films that have aged poorly when they run into the problem of having no foresight. Case in point, the 1990’s movies that tried to explore the new wonder that was the Internet. Movies like The Net (1995), Hackers (1995), and Johnny Mnemonic (1995) have all unfortunately become products of their time because they didn’t have the foresight to think that the Internet and computers would run on something other than floppy disks and dial-up service. Indeed, the world changes around us, but celluloid is forever, and when we look back on these movies, we begin to understand how fleeting a fad in our culture can be.

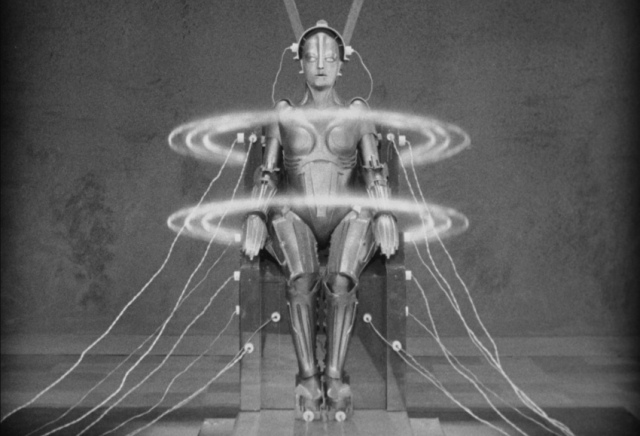

But it’s not only an outdated trend that can hurt a movies reception over the years. Sometimes it’s the progress in cinematic tools that causes a movie to lose some of it’s luster over time. Visual Effects have always played a part in film-making, but different advances can make movies in the past feel out of date by comparison. Stop-motion for example was a popular way for filmmakers to bring to life some of the most memorable monsters the big screen has ever seen. Animator Ray Harryhausen became a legend in the field because of his ability to make the impossible possible with his imaginative puppetry in films like The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Stop motion was a successful tool all the way up to the 1980’s, helping to even create memorable moments in films like Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) and Beetlejuice (1988). But once the CGI animated dinosaurs made their first appearance in Jurassic Park (1993) filmmakers pretty much abandoned the tried and true stop-motion for the wonders of digital manipulation. It’s usually a huge 180-shift like this that can make a once classic film feel quickly dated. Even advances in CGI over the years reflect poorly on films made at the very beginning of the era. The Sean Connery-voiced dragon in Dragonheart (1996) was seen as groundbreaking in it’s day, but when you compare it to the more advanced and photo-realistic Smaug in the Hobbit series, you start to see the artificiality of the original character. Indeed, CGI as advanced so quickly in the last 20 years, that movies made even a few years ago can feel out of date just because their effects are not up to today’s standards. It’s any wonder how Jurassic Park has managed to still amaze audiences with it’s effects after all of these years.

Now while many films have succumbed to the changing tastes of audiences over time, there are other movies that unfortunately are asking to be ridiculed for being so dated, and those are the films that naively try to predict the future of society. These movies are either bold visions of a progressive and homogenized society of the future, or are dystopian cautionary tales. Either way, each of these movies try to showcase what the future will be with the knowledge that they have with them at the time, and sometimes even the best guesses don’t really pan out so well. Particularly in the genre of Sci-fi do we see the most films that you can consider as dated. Many space age movies of the 50’s thought that we would have discovered life on Mars by now, or have colonized the moon. And remember movies like The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) or the Amazing Colossal Man (1957) where it was believed at the time that exposure to radioactivity could give you mutant powers, instead of cancer. Sometimes even a dystopian view of the world ends up dating a movie. Even great dystopian movies like Blade Runner (1982) make the fatal mistake of trying to put a definite date on their futuristic setting. The fact that we in 2014 are now just 5 years away from the future seen in that movie does not reflect well on how well the film imagined the future. But then again, Science-fiction is all about letting the imagination go, so it’s one that we can give it a pass on. But, movies like Logan’s Run (1976) and Rollerball (1975) don’t have that kind of luxury because their visions are so limited. They’re futuristic visions are only reflexive of the time periods in which they were made, making it seem like they believed that no advances in technology or culture would be made in the intervening year. This is primarily the reason why so many of these films tend to fall prey to the evolving tastes in cinema.

But, while some films that are a product of their era can age poorly, there are others that inexplicably live on for many years. This mainly has to due with how well the films are made and how timeless their themes and stories are. You can see this clearly in the lists made of all of the best films made over time. The one thing most of them have in common is their rewatchablitity. Movies like Lawrence of Arabia (1962), The Wizard of Oz (1939), The Godfather (1972), and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) can be watched over and over again many years removed from the time periods they were made because they did the same things exactly right; they didn’t try to reflect their own time periods and instead tried to remove themselves from the pack and try to be more universal in their appeal. And most importantly, timeless films like these embody their own unique worlds and exist by their own rules. A great timeless film doesn’t try to follow trends, nor is it seeking to try to start them either. There are exceptions though. The era of wartime propaganda message films in the 1940’s gave us a lot of dated and stilted films that barely are remembered years later; but out of this same pack we got Casablanca (1942), which is still considered one of the most timeless films of it’s era. And the amazing thing about Casablanca is that it was never meant to be anything more than another product of it’s time. Sometimes, timeless films just happen and then there are those that end up being discovered.

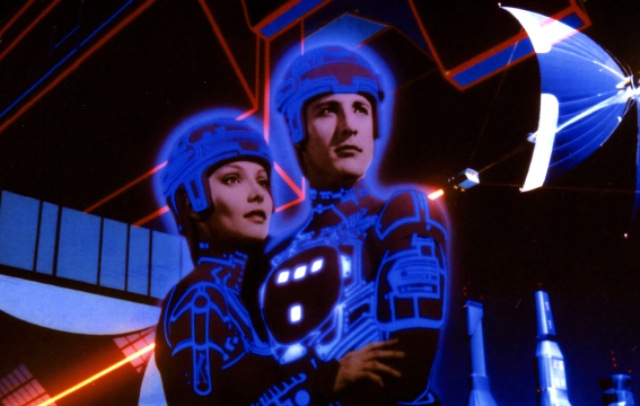

What is amazing sometimes is the fact that movies that should be dated end up achieving a timeless quality, partly due to the effectiveness of their story. Another factor however is the nostalgia factor. Sometimes we are in the mood for a movie that is clearly a product of it’s time and our entertainment values comes from how poorly the film has aged. That, or we just want to examine how the world was viewed in a time other than our own. One such movie that became a cult hit due to it’s very definitive vision of it’s time period was the 1982 Disney film Tron. Tron is a poster child for 80’s cinema, with it’s blocky CGI-based environments, it’s excessive use of back-lit colors, and it’s synthesizer-based soundtrack. Not to mention the fact that the plot revolves around the world of Arcade games. And yet, the movie is still beloved all these years later because it feels so uniquely of it’s time. It even spawned a sequel in 2010 called Tron Legacy, which itself smartly kept the aesthetic of the first movie while still updating the technology behind it. Other films from specific eras have also withstood the test of time due to the fact that vision behind them is so imaginative that they end up defining themselves, and the era they came from; such as Barbarella (1968) or even Star Wars (1977). Sometimes, even taking a timeless source material and adapting it for a certain time period helps to make a film resonate many years later. The 1995 film Clueless is definitely a product of it’s time, and yet it still resonates years later, mainly due to the fact that the story is from a classic source; Jane Austen’s 1815 novella, Emma. Smartly combining the classic story with a contemporary setting, filmmaker Amy Heckerling was able to make a film that felt timeless in it’s themes, but also be a commentary on the time in which it was made, thereby transcending it’s 90’s aesthetic.

But what usually happens is that we don’t know what’s going to be the definitive movies of an era until that time period has passed us by. And any attempt we make to proclaim a certain film as the best reflection of our culture at any certain time will fall under scrutiny over time. Sometimes, a movie takes many years to be considered an all time classic, while others fade into obscurity after a brief time at the top. This is sometimes reflective in the choices made during Awards season. What we thought was the standout film in one particular year may end up being forgotten by decades end. American Beauty (1999) was once considered a daring choice for Best Picture at the Oscars, but now it’s viewed as a forgettable and somewhat naive movie about middle-class malaise. Considering that there have been so many imitators in the years since American Beauty won, that brave choice now is viewed as the safe bet, especially when you look at all the other groundbreaking films that came out that year that have gone on to become classics; like The Matrix and Fight Club. Sometimes, it ends up working in a movie’s favor to be the underdog, because then you’re not left with the mark of the era in which you were made; that is as long as you still have that timeless quality about you. But withstanding the test of time can also be unpredictable. I’m sure that Robert Zemekis never thought that his small, time-travel comedy called Back to the Future (1985) would become a decade-defining movie, but it ended up doing just that. Sometimes it’s not the awards that define a classic, but the way it touches an audience, and even the smallest and silliest of movies can end up overshadowing the most prestigious of productions when all is said and done.

That is what ultimately separates the timeless from the dated; the impact that they leave on us. It is entirely unpredictable how well a film will age over time, but when we benefit from hindsight, we can see the trademark signs of what leads to so many movies becoming forgotten. But, even still, the very fact that a movie has not aged well doesn’t mean that it can’t still entertain. Indeed, the most dated of movies are the ones that enjoy the most dedicated of cult followings. Take for instance the movies of Ed Wood or John Carpenter. Their movies are very much cemented in their particular eras, and yet movies like Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) and Big Trouble in Little China (1986) can still leave audiences satisfied. Also, there are films that transcend their eras by taking the aesthetics of the period and working them to their fullest potential. Stanley Kubrick’s movies in particular should all feel dated, and yet every single one is considered a masterpiece of it’s era, mainly due to the un-compromised vision behind it and the timeless themes, which helps to elevate his films beyond the aesthetic. After a while, all films will be viewed differently, because cultural tastes are constantly evolving. Even beloved timeless movies that we proclaim about now may end up being viewed in a different way by future generations. It’s a challenge for filmmakers, but for film lovers, exploring the past is a fascinating journey into cultural history, because cinema preserves a place in time better than any other art form. It’s the best kind of historical time capsule and the longer that a movie withstands the test of time, the better it is observed as a landmark of our culture.