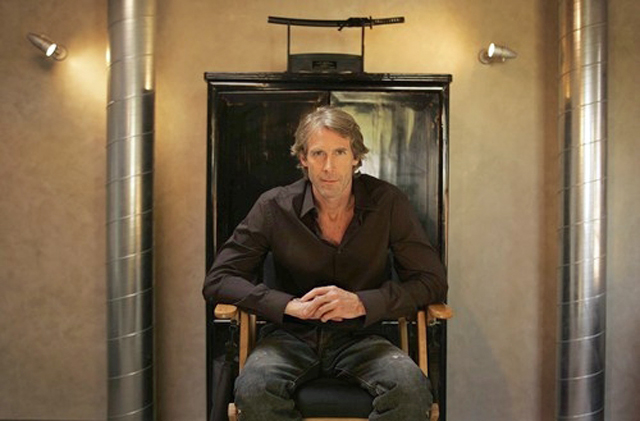

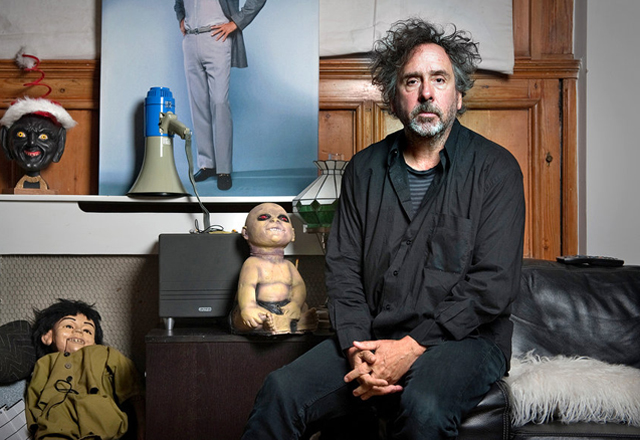

A lot of filmmakers come into the business knowing exactly the path they want to take to become a success. For many, they get their training, build their network, develop that killer concept that will gain attention from the industry, and then get that directorial gig that they always wanted. For some, the road to success can fall into place like they expected but for many more others, it doesn’t work out that way. The last thing that an aspiring filmmaker should do is enter the business with rigid expectations, because that’s not how the industry works. Oh sure, Hollywood expects much when it comes to results, but the who and how of getting there is much more random. The sad reality is that many people who come to Hollywood never make it in the business, and for some of them, it’s because the road to success never worked out the way that they expected. What’s best for most aspiring filmmakers is to take the opportunities that come your way, even if they aren’t the ideal ones that you wanted in the first place. Because the interesting thing about how Hollywood finds it’s talent is that they usually come out of the most unexpected of places. Take the career of Tim Burton for example. Burton certainly had ambition to work within the film industry, but when he started out, he believed that it would be in the world of visual development and animation. I don’t think he ever saw a prosperous career as a live action film director as his final destination, let alone as one who’s unique visual style has managed to be his greatest asset. But, that’s exactly what happened to Mr. Burton, and even more shockingly, it happened very rapidly and early on in his career. Tim Burton is the quintessential example of taking the opportunities that open up to you and never second guessing yourself along the way.

What makes Tim Burton so unique as a filmmaker is the uncompromising visual style that has become his trademark. Before working in live action, Burton was cutting his teeth as an illustrator and animator. He was trained at the prestigious CalArts Institute where his classmates included future titans of animation like John Lasseter and Brad Bird. He would follow with them into a post graduate career as an animation trainee at Walt Disney Animation. Though Burton was praised for his talents as an illustrator, it was clear early on that he was an outsider at Disney, since his style was often seen as too bizarre or graphically grotesque. After spending years being forced to assist on cutesy animal characters for films like The Fox and the Hound (1981), Burton tried to demonstrate for the Disney company areas in which his unique style could work. He spent his free time working on a stop motion animated short called Vincent (1982), a black and white piece that was a homage to classic horror and the iconic personage of one of his idols, actor Vincent Price. In addition, he also did designs for the monsters in Disney’s upcoming adaptation of The Black Cauldron (1985) as well as pitched his own original idea for a holiday special, which would later form the basis for The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993). Suffice to say, none of his attempts won Disney over, and he soon left the studio completely. Soon after, he directed a short live action film called Frankenweenie (1984), which got the attention of comedic actor Paul Ruebens, who was looking for a director with a unique vision to bring his Pee Wee Herman character to the big screen. With this opportunity, Burton suddenly went from failed animator to film director in quick succession. Pee Wee’s Big Adventure (1985) became an instant cult hit, which got the attention of Warner Brothers who gave Tim Burton another opportunity to showcase his unique vision with the macabre comedy Beetlejuice (1988). That film also became an instant hit, which then convinced Warners to hand Burton their most plum jewel of all; Batman. And with that, Burton suddenly was a household name, and it was all about taking the opportunities once they fell into his lap. In this article, I’ll be looking at the essential elements that make Tim Burton’s films what they are, and how they’ve defined his work as a filmmaker over so many years.

1.

GOTHIC, GRAND GUIGNOL, AND B-MOVIE

More than anything, it’s Tim Burton’s visual style that defines him as a filmmaker, and it’s the thing that you can find traces of in pretty much every movie he makes. And the thing that most people would label his style as would be Gothic. While there are certainly Gothic inspirations to be found in his movies, Burton doesn’t always limit himself to just that. His illustrative style, particularly found in the pre-production drawings that he makes himself for every movie, can be described as twisted and macabre, and for many, what they see in his illustrations reminds them a lot of Gothic architecture. But, where Tim Burton really draws his inspiration from is how the Gothic is diffused through cinema and theater. The burlesque tradition of Grand Guignol theater certainly can be found in Tim Burton’s work, because of it’s embrace of the macabre and the carnival-esque. That’s something you see working together a lot in Burton’s films, visuals and story elements that appear sinister and foreboding, but are dealt with in a cartoonish fashion. Which also stems from another inspiration for Tim Burton, which is B-Movie Hollywood. In particular, Tim Burton’s movie’s celebrate the way in which Gothic visuals were presented through the cheap and often ridiculous production design and visual effects of the B-Movies of the 50’s and 60’s. To Burton, these movies had their own charm, which is why he often pays homage to them. You can see the pull between the grotesque and the cartoonish in many of his films like Beetlejuice, Alice in Wonderland (2010), but he also manages to find the right balance when he heads towards any of the extremes, especially when he makes something fully Gothic (1999’s Sleepy Hollow), Grand Guignol (2007’s Sweeny Todd), or B-Movie (1996’s Mars Attacks). He even devoted an entire movie to honoring one of the sources of his inspiration with 1994’s biopic of the worst B-Movie director ever, Ed Wood. Despite having an uncompromising visual style, Burton has somehow managed to focus it through these multiple inspirations and that’s made him surprisingly versatile.

2.

SUBURBAN ANGST

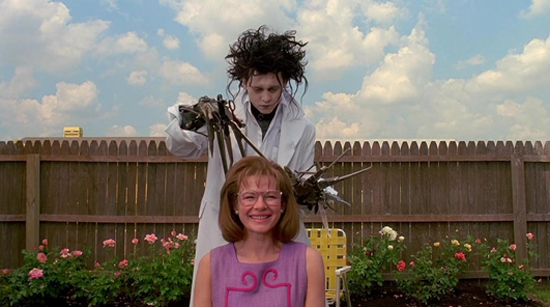

Apart from his visual inspiration, Tim Burton is also attracted to stories that appeal to his own sensibilities, particularly ones that speaks to him as an individual. One of the most common themes found in his movies is the anxiety of living in a homogenized, featureless world, specifically funneled through the lens of suburban encroachment. When you see someone of Tim Burton’s ilk, or watch any of his movies, you might imagine that he came from some cold, dark and old-World community. But that’s the case at all. He was born and raised in bright, sunny Burbank, California, which is not macabre or Gothic in any way. And yet, his childhood years in Burbank is reflected in his movies, particularly when Burton focuses on the clash between the past and present. He may not state it clearly in his films, but I think that the urban sprawl of Los Angeles into the San Fernando Valley during Burton’s childhood left a strong impact on him. In the late postwar years of the 50’s and 60’s in which Burton grew up, many of the Victorian style homes and buildings found throughout Los Angeles were being torn down and replaced with rows and rows of identical single level house in a widening urban sprawl. In a way, Burton witnessed the final days of a Gothic Los Angeles that no longer exists, and his movies often feel like a lamentation on that. In many of his films, the monsters are found in suburbia and not in the spooky old houses. This is best represented in the movie Edward Scissorhands, where a modern suburban community engulfs an old manor house, and where a lonely “freak” hides from a neighborhood that doesn’t understand him. You see varying interpretations of that in other films like with Beetlejuice (1988) where the bourgeois suburban family takes over an old Victorian country house and “modernizes” it, or in Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children (2016) where the hero leaves suburban Florida to live in an old house that literally exists in a nostalgic time loop. But the narrative of Edward Scissorhands in particular illustrates this special aspect of Tim Burton’s work, because it offers an interesting insight into the kind of world that he values.

3.

THE OUTSIDER

The other major theme found in most of Tim Burton’s films is the focus on the “outsider.” Being a pale kid interested in the Gothic and the grotesque while growing up in the Los Angeles suburbs probably made Burton feel like an outsider himself, and that’s why he finds so much sympathy in stories that spotlight those who are shunned or isolated in society. In particular, Burton’s movies often spotlight the ones we often label as the “weirdos” or “freaks.” Oftentimes these kinds of characters are heroes in his movies, but he also devotes a lot of attention to villainous oddballs as well. This is probably what made him such a strong fit for the Batman franchise. In both Batman (1989) and Batman Returns (1992), you can see his fascination with “freaks” that exist within a society and how their peculiar identities spark the clashes that they get involved in. Tim Burton’s Batman villains, Joker (Jack Nicholson), Penquin (Danny DeVito) and Catwoman (Michelle Pfeiffer), are just as damaged and corrupted by society as the hero Batman (Michael Keaton), only he has managed to use his freakish identity to elevate his community, rather than sink it lower. And with Batman, Tim Burton explores another interesting aspect of the idea of the outsider, which is the persona of the isolated genius. Bruce Wayne becomes a symbol of good in his community, yet still cuts himself off so that he can never be truly at peace as well. You see this same dynamic played out with Willy Wonka in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and with Margaret Keane in Big Eyes (2014), where the characters have created magnificent works of creation, and yet their social anxiety keeps them from ever feeling the joy of what their work has done in the world. It’s that fascination with those who are kept isolated from society, whether self-imposed or by some kind of prejudice, that makes the characterizations in Tim Burton’s films so vivid. Much like in how his own peculiarities have made him stand out in Hollywood, Tim Burton values the outsiders of his stories, good or bad, because they are the ones that we remember the most in the end.

4.

DANNY ELFMAN

Like many directors with a unique style, Tim Burton has kept a close knit group of collaborators through most of his movies, like production designer Rick Heinreichs and costume designer Colleen Atwood, as well as actors like Johnny Depp, Helena Bonham Carter, Eva Green, Christopher Lee and Michael Keaton who have appeared in multiple films of his. But, if there was ever a collaborator that had the most influence on making Tim Burton films feel distinctly their own thing, it would be composer Danny Elfman. Elfman, the once frontman of progressive rock band Oingo Boingo, has written the musical scores for all but two of Tim Burton’s films, the exceptions being Ed Wood, which was written by Howard Shore, and Sweeny Todd, which used the original Broadway score written by Stephen Sondheim. It was actually Burton in the first place that pushed Elfman into a career of scoring films, giving him his first big break with Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure. The combination of Elfman’s sound and Tim Burton’s visuals couldn’t be more perfectly matched, because Elfman likewise has a taste for the edgy, carnival-esque style. His music can go from whimsical to unhinged in a heartbeat, and the music often is just as memorable as the movies themselves. He also has shown incredible range from the sweet, nostalgia driven melodies of Big Fish (2003), to the terrifyingly chilly Sleepy Hollow, to epic grandeur of Alice in Wonderland. He even managed to encapsulate the iconic status of Batman in brooding piece that is now synonymous with the character. Naturally, when Disney finally accepted Burton’s dream to bring Nightmare Before Christmas to a reality, Danny Elfman was given the opportunity to score the film, but to write original songs as well. And that he did, with a musical that not only stands as one of Disney’s best, but also one that retains the unique Burton/Elfman character. Danny Elfman even provided the singing voice for the protagonist Jack Skellington, so you see his mark in Nightmare more than in any other film he’s worked on with Tim Burton. It’s one of the most special collaborations in all of film-making, because it’s one where both artists bring out the best in one another and gives each other’s work the magical element that helps it to stand out.

5.

BLACK AND WHITE AND COLOR

Tim Burton has his inspirations in aesthetics and themes, but there is definitely something about his sense of visuals that really sets him apart as well. In particular, Tim Burton is a director who likes to experiment with the use of color in his movies, and it’s a tool that he often utilizes to emphasize those same themes discussed earlier. In particular, Burton is especially drawn to the visual clash between stark black and white. Characters with striped clothing are especially common in his movies; most notably with Michael Keaton’s Betelgeuse and his trademark striped suit. It’s not particularly a visual trademark to emphasize a bad character, as good-natured Jack Skellington is also known for his striped outfit. The same can also be found with a character caught in between good and evil, like Johnny Depp’s Sweeny Todd. Burton also displays an interesting take on clashing colors with the duality of Batman and the Joker, with the justice seeking Batman cast completely in black, shadowy tones, whereas the Joker is white-faced and wears flashy colors. The use of color, and even the absence of it, are both important visual factors in Tim Burton’s style, no doubt taken from the sensibilities he formed as an illustrator. He surprising manages to maintain his style between the those extremes, with his style shining through even in black and white photography, which he showed in Ed Wood and his animated Frankenweenie remake from 2012. At the same time, he can also splash a lot of color into a scene, sometimes with the intent of emphasizing the grotesque nature of something. This can be found in scenes of gore from Sleepy Hollow, where the especially red blood stands out amongst the gray landscapes, or in the garish plastic world of the suburbs in Edward Scissorhands with the pastels and neons almost aggressively applied. Tim Burton makes deliberate choices when it comes to colors, whether it be applied to characters, a setting, or the movie entire, and it’s often deliberately done to cast his stories in clear black and white terms with the actual clash of black and white, or bold color.

Tim Burton, whether his style appeals to you or not, is no doubt a one of a kind in film-making. Few other directors have been fortunate to have their visual style brought to the screen un-compromised, and even less have succeeded with a style as weirdly refreshing as Tim Burton’s. It’s also amazing how Burton almost kind of stumbled into the business, not really realizing how quickly it would take off. I’m sure that he always dreamed of making his own films, but I don’t think that he ever saw himself becoming the icon that he is so quickly. He probably imagined he’s be some kind of underground artist, rather than the man tasked with bringing Batman to the big screen. But, he saw that door open before him and he walked through without ever looking back. Today, Tim Burton has one of the most unique filmmographies of any filmmaker, even if it’s not the most consistent. He’s had his fair share of disappointments too, with his 2001 remake of Planet of the Apes being probably the least effective representation of his talents as an artist. He has had a shaky track record as of late, with the good (Frankenweenie, Big Eyes) often overshadowed by the bad (Alice in Wonderland, Dark Shadows). But even still, Hollywood still trusts him with high profile projects, some of which seem to be almost tailor-made for his unique style. It’s funny how the company that once shunned his art, Disney, are the ones who’ve since fully embraced it. The current slate of live action remakes to animated classics feel very much inspired by the Tim Burton aesthetic, which easy to see because it was launched primarily with his Alice in Wonderland adaptation, and continues now with his newest version of Dumbo, out this very week. His films still have that unique Burton feel, but it was never stronger than in his earlier years when he first was starting out. Those first five features of Pee-Wee, Beetlejuice, Batman, Edward Scissorhands and Batman Returns are what really made Tim Burton a legend. Quite simply, there was no one else who was making movies like him, nor had the kind of creative ideas that could make it to the big screen in tact like he had. Since then, he’s grown more mainstream, and his legacy is becoming more and more harder to live up to, but there’s no doubt that he left an indelible mark on the industry. And it’s a mark that’s made it more acceptable in Hollywood to be an “outsider” and a “freak,” because in many ways they are the ones with the best stories to tell.