Roll back the clock to the 2000’s. The state of Comic Book movies in the mainstream was in a much different situation than it is now. The 90’s came to close with the genre in it’s worst state, following the box office and critical failure that was Batman & Robin (1997). While the DC Comics properties were firmly in the control of a single studio, that being Warner Brothers, their comic page rival Marvel was not so lucky to have a sole proprietor making decisions over it’s cinematic fortunes, both good and ill. Marvel was coming out of near bankruptcy in the mid-90’s, and to salvage their financial status, they freely spread out the cinematic rights to their characters and storylines to whomever was interested in them. As a result, the rights to Marvel properties were spread around to most of the major studios in Hollywood. Sony took Spider-Man and his associated company of heroes and villains. Fox won the rights to the X-Men and the Fantastic Four. Meanwhile, fitting of their history of monster movies, Universal became the home of The Incredible Hulk. The rest, who many believed at the time were second tier characters like Iron Man, Thor and Captain America, went to Paramount, who for a while did little with their Marvel properties. In the early part of the 2000’s, the studios that did have Marvel characters in their possession did quite well. Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man (2002) broke box office records for Sony Pictures, while Bryan Singer’s X-Men (2000) was hailed as a refreshingly mature take on the often silly genre. There were, however, some disappointments as well, with Ang Lee’s Hulk (2002) becoming a convoluted mess, and Tim Story’s Fantastic Four (2005) feeling like an undercooked portrayal of Marvel’s first family. Sequels to the X-Men and Spider-Man movies also fell off for fans in later years, and many were wondering if Marvel was even capable of competing with the likes of DC in sustaining long lasting franchises. The ante was upped even more after Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins premiered, a critically acclaimed revival of the Batman franchise that put DC back on firm ground again. Marvel would answer, but the way they would do would change everything we thought we knew about comic book movies.

The Spider-Man franchise over at Sony Pictures was spear-headed by a powerful Executive Producer named Amy Pascal. To this day, she still retains exclusive rights to produce Spider-Man movies, but her time in the comic book world left a much different impact than that. One of her assistants that she mentored during the making of Spider-Man was a up-and-coming producer named Kevin Feige. Feige was very much a person who lived and breathed comic books, and he was eager to change the way super hero movies were made by pushing them to adhere closer to what was on the page. There seemed to be a feeling in Hollywood that comic book movies needed to be more like action movies. Storylines were more grounded and simple. Gone were the tights and in were the dark leather suits. It’s almost like the industry was ashamed that these popular characters came from such a colorful and imaginative source such as the comic book page. Feige didn’t believe any of that. He wanted to see the characters pop right off the page in all their colorful and sometimes cheesy glory. He understood that these characters were larger than life, and that the movies needed to embrace this aspect about them in order to do the characters justice. You can feel that a bit in the Spider-Man films from Sam Raimi, which definitely embraced more of the charming quirkiness of the comic books, and it wouldn’t be surprising if this is what Feige imagined for all the other characters as well. By the time Spider-Man 3 (2007) came out in theaters, Feige was already working a plan to change the future of Marvel on the big screen. He convinced the leadership of Marvel Comics to invest in a new in-house production company that would supervise the creation of all future Marvel movies at all the studios, insuring a consistency across all their properties that would define them first and foremost as a Marvel film. Thus began the existence of Marvel Studios.

Marvel Studios would work with all the different studios on their selectively held properties but all the creative choices, such as casting and which stories to tell, would be run through Marvel Studios offices. As a result of this change in creative leadership, the decision was to abandon most of the franchises that had been developed up to that point and instead reboot many of the characters. This, however, was easier said than done, as Fox was insistent on continuing on with their popular X-Men franchise as it was; especially since they had a bankable star like Hugh Jackman still going strong as Wolverine. The other studios were more inclined to rethink the future, and at this point, Paramount was ready to finally begin using the Marvel properties they had been sitting on. It was with Paramount that Feige saw a really golden opportunity to try something that hadn’t been done before ever with the super hero genre. Instead of having each character exist within their own stand alone franchise, Feige and company theorized the possibility of having all their comic book characters share a single connected universe. Not only would they have their own stand alone movies, but the characters would be able to meet each other and crossover; even forming a super team. Kevin Feige knew this would be an ideal thing for Marvel to undertake, because it’s exactly what the comic books had been doing for decades before. It’s not a novel idea; DC had been trying to jumpstart a Justice League film for years before, and both the Superman and Batman franchises featured Easter eggs referencing the different heroes in their films many times; same with early Marvel films too. But the stars had not aligned until now. With Marvel Studios now assuming creative control, they were ready to give it a try, and the starting point would be with the trio of heroes that the industry had before believed were second tier.

Paramount announced that they were greenlighting new films based on the Marvel super heroes Iron Man, Thor, and Captain America. These were untried properties, with only Captain America having one cheaply made for TV movie in the past. But, Marvel Studios believed that this was the right batch of characters to begin plans for a bigger universe. But, the all important question was who would be the one taking on the responsibility of starting this new era on the right foot. The answer came with Iron Man (2008). There had been attempts to bring Iron Man to the big screen before. For a while, Tom Cruise was attached to play the role of Iron Man and his alter ego, billionaire playboy Tony Stark. However, Cruise’s busy schedule conflicted with Marvel Studios’ plans, and the team decided to go in a much different direction than what he was planning to do with the character. For Iron Man, Marvel Studios needed to not just make the actor look good in the suit, but they also needed to make him interesting outside of it as well. The task of adapting the character to the big screen fell to actor/filmmaker Jon Favreau, who was coming off of a successful stretch of films such as Elf (2003) and Zathura (2005). He too was an avid comic book fan who was eager to do justice to the character of Iron Man on the big screen. But, who other than the unavailable Tom Cruise would be ideal for the role. Favreau’s first choice was a rather surprising one. Robert Downey Jr., a long time character actor in Hollywood, was not what many would consider to be a bankable star. His career was nearly destroyed by his drug addiction and the time he served in prison. He had recently earned high marks for a comeback performance in Shane Black’s Kiss, Kiss, Bang, Bang (2004), but many still thought he was too much of risk to headline a major studio film. But, Favreau saw in Downey’s persona exactly what was needed for the role of Tony Stark, and he convinced Marvel and Paramount to take a chance by giving him the role. The rest of course is the stuff of legend. Downey was the perfect Tony Stark and his presence on screen carried the film to remarkable commercial and critical success. But Iron Man the movie also offered up another surprise for audiences. A post-credit scene introduced another famous comic character named Nick Fury, played by Samuel L. Jackson, who was there to introduce what ultimately would be the future of Marvel films for the next decade and beyond; the Avenger Initiative.

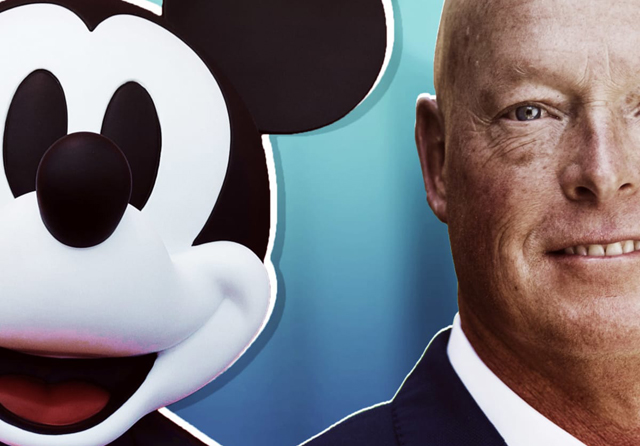

Marvel Studios had proven itself with the crazy success of the first Iron Man movie, and they were ready to continue with the next phase of their plans, which was to get the other films in the pipeline going. They got a strong assist that same summer with Universal successfully rebooting The Incredible Hulk with Edward Norton playing Dr. Bruce Banner. They were even able to tie that film in with Iron Man by giving Robert Downey Jr. a surprise cameo at the end before the credits. But, a surprising development happened in the wake of Iron Man’s success. In 2009, Disney, which had up to this point been out of the super hero game entirely, decided they were ready to get in on the action. Unfortunately for them, the other Hollywood studios had already licensed all of the prime properties that Marvel had to offer. So, what did they do? Well they decided to buy up Marvel outright, to the tune of $4 billion. This purchase included Marvel Studios in the package, so now Kevin Feige and company had a new set of overlords to answer to. Thankfully for them, Disney CEO Bob Iger was willing to be hands off as long as they could deliver the same way they did with Iron Man. Surprisingly, Disney was also able to secure back the licenses from Paramount without struggle, which meant that they would be the ones in charge of the upcoming Thor, Captain America, and Avengers releases, as well as an Iron Man sequel. Universal maintained their Hulk license, but were willing to work with Disney in adding the big green guy to the Avengers team up, which became necessary because Edward Norton left the franchise after one film. Sony and Fox remained defiant in holding firmly to their exclusive rights and keeping them out of Disney’s hands. Still, Disney was able to work with what properties they had. Then unknown Australian actor Chris Hemsworth was given the role of Thor, while actor Chris Evans (who previously played The Human Torch in Fox’s Fantastic Four) was cast as golden boy super soldier Captain America. Mark Ruffalo replaced the absent Edward Norton in the role of Hulk, and lesser know heroes like Hawkeye and Black Widow were added to the mix, played by Jeremy Renner and Scarlett Johansson respectively. This was the original team assembled for The Avengers (2012), and again Marvel changed the world of comic book movies forever.

It became clear after The Avengers that Marvel Studios was not just a Hollywood success story, they were a force to be reckoned with. Now that they finally had a home studio base with deep pockets like Disney to finance all of their future plans, they could indeed create that shared comic book universe that Kevin Feige had long dreamed would be a reality on the big screen. The first four years of Marvel Studios output was deemed Phase One, and that every collection of films thereafter that would ultimately culminate in another Avengers team up would be another new phase. Over time they introduced a whole lot more of the Marvel family to the big screen, including long anticipated debuts of fan favorites like Doctor Strange, Black Panther, Scarlet Witch, The Vision, and Captain Marvel. They even managed to turn a very obscure comic property like Guardians of the Galaxy into a smash hit with audiences and critics alike. Sony even decided it was in their best interest to play nice, and they granted the use of Spider-Man in their Avengers team ups. At that point, only Fox remained the lone hold-out; but Disney and Marvel were still able to build their universe without the presence of the Fantastic Four or the X-Men. The question however was where it was all going to lead. Audiences had become invested in this cinematic universe to the point where they were following it like it was the biggest serialized TV show ever made. But in every narrative, there had to be a purpose to it, and for Marvel’s endgame, they turned to the comics for inspiration. Typically, comic books lead their ongoing storylines to major events, and one of the most famous in Marvel comics history was an arc known as the Infinity War. In the first three phases of what had become known as the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) there was this connecting thread of powerful gems known as the Infinity Stones being discovered by the characters. The stones were coveted by a powerful being known as Thanos (played by Josh Brolin), who ultimately used its’ power to reshape the universe. Marvel Studios masterfully wove in this storyline across 20+ films, and it resulted in two monumental films Avengers: Infinity War (2018) and Avengers: Endgame (2019), both of which wrapped up the decade long arc in perfect fashion. The MCU managed to achieve the unthinkable, which was to successfully tie in all of their many franchises into a satisfying conclusion to an epic storyline. Kevin Feige had achieved his dream of bring the comic book universe completely to life.

But, where do you go after you’ve conquered the world. By the time Avengers: Endgame had been released, Marvel had become the most valuable entertainment brand in the world. Not only did Disney make back their $4 billion investment; they were able to use their gains to acquire Fox itself, thereby bringing in the last holdouts of the Marvel properties still out in the wild. With no more roadblocks in their way, they really could do anything they wanted post-Endgame. So, what were they ready to do in Phase Four. This new phase was something of a reboot for Marvel. The storylines that led up to the Infinity War were now complete, with legacy characters like Iron Man and Captain America getting their farewells. Now it was time to look towards the next event. For the new phase of Marvel, Feige and company decided the new direction would focus on what is known as the Multiverse. And once again, Marvel is finding itself in uncharted territory with this new undertaking. The multiverse is a concept that’s a bit harder to sell to audiences than easy to identify McGuffins like the Infinity Stones. The plan has offered up some fun ways to explore the multiverse, like current Spider-Man Tom Holland getting the chance to appear alongside his predecessors in the role, Tobey Maguire and Andrew Garfield, in Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021). But other uses of the concept feel underdeveloped like with Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022) which didn’t go far enough into the multiverse. Plus, you see the struggle Marvel is having with establishing their new big baddie for this long arc saga; the multiversal menace Kang the Conqueror (which isn’t helped by Kang actor Jonathan Major’s on-going, at the time of this writing, legal troubles). For the first time in it’s 15 year history, Marvel seems to showing some growing pains; like the level of success that they have managed to achieve is now starting to weigh down on them and undermining their focus. One thing that could be affecting this shaky ground that they now stand on is the fact that Marvel is also devoting part of their master plan to Disney’s aggressive expansion into the streaming market, with Marvel Studios creating long form series and specials for Disney+. Where in past years there was room to build anticipation between each new Marvel film, now Marvel is releasing new properties throughout the entire year. And for audiences, it’s proving to be too much of a good thing. That’s why Marvel’s Phase Four has had the most mixed response to date of any of Marvel’s MCU plans.

Now, looking back in all the fifteen years of existence of the MCU, has Marvel finally lost it’s golden touch? In many ways it’s still relative. Compared to it’s own past success, Marvel is underperforming a tad bit in it’s recent offerings. Earlier this year, Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania (2023), the film meant to launch Phase Five of the MCU, became the first film widely accepted by both the fans and the critics as the least successful film from Marvel to date. It’s not the biggest money loser, which goes to Eternals (2021), but it can’t blame it’s poor box office on lingering effects of the pandemic either. Even still, most of their movies are still out-performing competitors from other studios. Sony’s non-MCU Spider-Man character movies have not performed as well, with last year’s Morbius (2022) being a pretty embarrassing flop for them. And the whole last decade for Marvel’s rival DC Comics has been defined by Warner Brothers desperately trying to play catch-up, with some pretty disastrous results. The failure of their Justice League (2017) movie is a particular case study in how studio interference can ruin a franchise, and it took a grass roots effort on line to get a better director’s cut released to finally satisfy the fans. Even the less successful Phase Four projects still perform well when compared to the rest of the market; I’m sure DC wishes they had Quantumania’s over $200 million take in domestic box office. Honestly, Marvel has been in this boat before. Phase Two had it’s shaky moments too before things finally revved up in Phase Three leading up to the Infinity War. For any studio to maintain this kind of level of success this long is pretty miraculous, and Kevin Feige, Disney and everyone who worked on these movies should feel a sense of pride that they are still doing fairly well even as audiences are a bit mixed lately. You definitely have to credit all the things they have done right to make themselves the juggernaut that they are. Having the strong foundation of Iron Man was a key part of that. It was risky trusting the future of comic book movies with someone of Robert Downey Jr.’s reputation, but he persevered and his career resurrection is one of the greatest redemption stories in movie history. 15 year later, Marvel is on top of the world and it still has more stories to share, which will hopefully continue to fulfill the hopeful vision that Kevin Feige and Marvel Studios set out to accomplish. As the legendary Marvel Comics icon Stan Lee always said: “Excelsior.”