There are many filmmakers that people can point to as the ones who molded and shaped the horror genre into what it is today; Wes Craven, John Carpenter, Sam Raimi, and Joe Dante being among the most noteworthy. But if there was someone who people consider the grandfather of modern horror, the name of Alfred Hitchcock comes to mind. Which itself is strange, because Hitchcock was not exactly a horror filmmaker. Only one of his movies could be considered a horror film, his iconic 1960 thriller Psycho, but it was such a high water mark for the genre that it would change horror film-making, and cinema for that matter, forever. But, apart from that, Hitchcock’s true title in Hollywood was “the Master of Suspense,” which he had earned over the course of his career having directed some of the most exhilarating and tension filled movies that were ever committed to celluloid. Murder mysteries were his main foray, as the majority of his filmography was devoted to crime dramas and whodunits. But it wasn’t just the suspense that made him an icon as a director, it was the way he presented it. Always an innovator, Hitchcock would find new ways to keep his audience on edge, and that included introducing untried techniques that for their time were cutting edge. These included gimmicks like the long unbroken takes in the movie Rope (1948), the dolly zoom in Vertigo (1958), or the frantic cutting of the shower scene in Psycho. He was a director that always played by his own rules and he thankfully found success making the kinds of movies that he wanted to make; which was a rarity in the Hollywood system during his heyday.

What’s also interesting about Hitchcock is that while there is a distinct character to all his films, since he rarely strayed away from the suspense genre, there are also definable phases to his career too. He started out in his native England making spy thrillers like The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), and Foreign Correspondant (1940), which garnered the attention of Hollywood. He was swayed to cross the pond by mega-producer David O. Selznick to produce a series of dramas for his independent studio. The first one was the Oscar winning Rebecca (1940), followed by Suspicion (1941) and Spellbound (1945). While the movies under Selznick Pictures are still expertly crafted and feature some of the director’s best work, you can also tell that Hitchcock was feeling a little handcuffed at the same time, as these movies were more or less his most mainstream and micro-managed films of his career, with Selznick having much oversight over the final products. After the Selznick partnership, Hitchcock made his way to Universal Pictures, where he would remain for the rest of his career, leading to his most prolific run of movies. At Universal is where Hitchcock became the director that we know today, with full, unwavering confidence in his abilities as a director. And the movies are one classic after another; Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Notorious (1946), Rope, Strangers on a Train (1951), Rear Window (1954), Vertigo, Psycho, and The Birds to name a few. He even became the face of suspense thrillers, as Universal also produced an anthology TV series called Alfred Hitchcock Presents, with the director appearing in front of the camera to introduce each episode. Because of all this, Hitchcock had become a new kind of filmmaker, which was one who had become a household name. Some directors had become noteworthy in their time, but only the name of Hitchcock could be immediately identifiable in every American home, and that was quite a feat for his time. Even to this day, Hitchcock is still one of the most celebrated, analyzed and frequently imitated filmmakers in cinematic history. What follows is a couple of elements that are uniquely a part of the Hitchcockian style, and what helped to define him as a a filmmaker.

1.

THE WRONG MAN

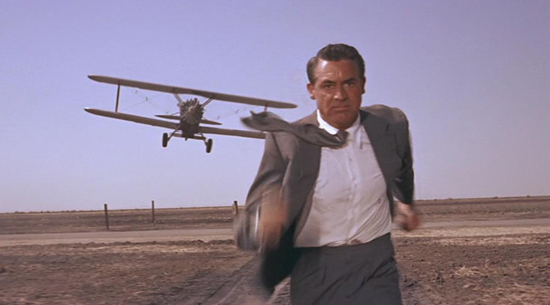

Hitchcock would often return to tropes that had served him well in the past, and he would manage to rehash them again and again without making it seem like he was repeating himself. One of those tropes that is unmistakably Hitchcockian is that of the “wrong man” scenario. Hitchcock liked nothing more than to have his protagonists thrown into a situation that they are ill equipped to take on. Most of the time this would involve the protagonist either by accident or by unfortunate ill judgment ending up in the middle of a larger conspiracy that they had no previous knowledge of. This trope goes all the way back to his early years, with his main characters in The Man Who Knew Too Much and The 39 Steps both finding themselves involved in the middle of a plot, which they never expected to be in. For the former, it happens when the villain (played marvelously by Peter Lorre) kidnaps the child of the hero (Leslie Banks), and the latter is when the hero (Robert Donat) is falsely accused of murder as part of a cover-up. Hitchcock favored this trope because he found it as a good way to build his protagonist’s character over the course of the story, allowing them to learn as we follow along with them in the story. It’s a great way to spotlight the charm and wit of the character as well, and he often liked to give some of Hollywood’s top leading men these kinds of roles, including Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart being among his very favorites. And just to show how aware he was of his own style, Hitchcock even made a movie called The Wrong Man (1956), with Henry Fonda playing the titular role. Despite being a long standing trope within his full body of work, there is probably no better use of it than the thrilling classic North by Northwest, with Cary Grant literally being the wrong man, at the wrong place at the wrong time. Of course, it’s not the trope alone that carries the movie, but what Hitchcock does after that makes the movie such a classic, taking Grant on a cross country adventure as he grows from simple business man to death-defying spy by movie’s end. It’s understandable that he continued to return to the same trope over and over again, because it served him well.

2.

AMERICANA

When Hitchcock came to America to make films for Selznick, I don’t think he initially realized the impact it would have on the rest of his career. The English-born director not only became a naturalized citizen of the United States, but he would also use his newly adopted homeland as a thematic element in most of his latter films. There is a strong presence of Americana throughout his movies made in Hollywood; some more overt than others. For one thing, Hitchcock loved to use distinctive American landmarks in his movies as important settings for moments in his films. These include the Golden Gate bridge where Kim Novak’s character nearly drowns herself in Vertigo; the climatic confrontation in Saboteur (1942), where Norman Lloyd literally hangs by a sleeve on the outstretched hand of the Statue of Liberty; and of course the epic chase across the faces of Mount Rushmore in North by Northwest. But Hitchcock was not spotlighting American landmarks out of some newly found patriotic fervor. They were part of his interesting introspection into the underbelly of America. He put these moments around landmarks just to show how extraordinarily out of place such a moment would be around these icons. He also distinctively tried to explore American society in the micro as well. Long before David Lynch would do the same with Blue Velvet (1986), Hitchcock explored how a seemingly peaceful suburban American community could be hiding something sinister underneath with the brilliant Shadow of a Doubt, which Hitchcock considered one of his favorites. Even Psycho follows in that same vein, with a seemingly unassuming little roadside lodge, typical of contemporary American travel culture, turning into a house of horrors by film’s end. Hitchcock was both a filmmaker that was fascinated with America and critical of it as well, and it provided him with a careers worth of interesting stories to tell, all of which have appropriately become American classics.

3.

THE ELUSIVE BLONDE

On the flip side of his trope of the “wrong man,” there is another character type that has become a part of the Hitchcockian style. And that type almost always is portrayed by a blonde haired beauty. People have often claimed that Hitchcock was playing out a fetish in movies by always having his leading ladies be blonde and impossibly beautiful, but that I think is a misreading of him as a director. In a way, Hitchcock cast his lead actress by the distinctive hair color because he felt that it represented a more angelic aspect to their character. It was also something that became more common once he started making movies in color, as his previous leading ladies from the black and white era like Ingrid Bergman and Joan Fontaine had distinctive brown hair. It started with the casting of Grace Kelly in Rear Window that Hitchcock became enamored with blonde female leads, and we would see a distinct through-line of leading ladies for the next decade, as Doris Day, Kim Novak, Eva Marie Saint, Janet Leigh and Tippi Hedren all followed in Grace’s footsteps. But, what is also noteworthy about the use of blondes in Hitchcock’s movies is that they are often drivers of the plots themselves; sometimes in tragic ways. Sometimes they are there as an accomplice to the male lead, like Grace Kelley in To Catch a Thief (1955) or Eva Marie Saint in North by Northwest, but oftentimes they would also be put into the path of peril. To Hitchcock, blonde was a sign of purity and having a blonde lady fall victim to violence only made the deed more tragic. He was probably fully aware of his obsession, since he made Jimmy Stewart’s protagonist in Vertigo so fixated on the blonde beauty that he tragically lost, to the point that he forces another woman to look just like her. It’s a fascinating aspect to his filmography that is unmistakable once you become aware of it. Hitchcock had a type in mind, but there is no doubt that the most important blonde lady in his life was his wife of 54 years, Alma Reville, who was his closest collaborator and creative confidant as well. And she was far from elusive.

4.

BERNARD HERRMANN

Apart from his wife, Alma, Hitchcock never had too many close collaborators over his career. His crews were often interchangeable depending on which movie he was making; he worked on scripts from a whole variety of screenwriters; and his production teams were often specialists specific for the different new experiments that he was trying to take on with each new film. But if there was one collaborator that did leave his mark on the work of Alfred Hitchcock, even if it was for a short amount of time, it was film composer Bernard Herrmann. Hermann was already a well established composer by the time he arrived in Hitchcock’s stable. He started in the business in a big way, scoring Citizen Kane (1941) for Orson Welles. For the next decade and a half he had worked up nearly 20 film scores, but once he met Hitchcock, things would take a very dramatic turn. Starting off with The Trouble With Harry (1955), Herrmann would score 7 total films for Hitchcock, the most of any film composer; and some are often cited as among the best ever written. His haunting love theme from Vertigo is one that instantly leaves an impression on it’s audience, and the rousing North by Northwest theme is a jaunting adrenaline rush. But perhaps Herrmann’s most brilliant work was saved for the movie Psycho, which some have proclaimed as his best overall. The main theme, with it’s off-kilter harshness is itself an already standout piece, and it does probably the best of any Hitchcock movie score to set the tone of a film. But Herrmann’s most brilliant choice as a composer is the one that seems the most deceptively simple. Instead of having the legendary shower murder scene play silently with only sound effects, as Hitchcock initially wanted, Herrmann composed an underscore of shrieking violins, which assault the viewer almost like they’re the ones getting stabbed. It’s a genius choice of music and is probably just as much a part of what has made that scene legendary as Hitchcock’s own direction. In many ways, it’s also probably the most imitated film music score of all time, which is a testament to Herrmann’s input. Hitchcock would have still continued to be an influential filmmaker, but who knows how different his career may have been had his movies not included Herrmann’s music in them.

5.

THE MCGUFFIN

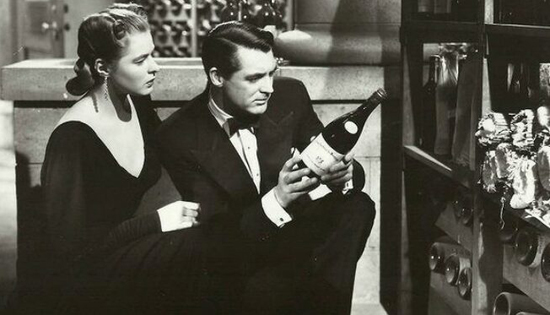

All us cinephiles are pretty aware of the term McGuffin by now. The term is used to describe an object that is central to the plot of a film, but inconsequential to the story. Famous examples could include the Maltese Falcon from the 1941 film of the same name; the Ark of the Covenant from Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981); the briefcase from Pulp Fiction (1994); you could even point to the six Infinity Stones as the McGuffins of the entire Marvel Cinematic Universe. But it might surprise you that the term actually came from Hitchcock himself. He didn’t coin the term (that was screenwriter Angus MacPhail), but he was the one who defined it. In Hitchcock’s own words, the McGuffin is “the thing that the characters are after, but the audience doesn’t care.” In other words, it’s the motivator for the human drama, and carries little significance apart from that. The McGuffin is just there to passively exist, so that the characters can go through all the highs and lows of the plot in order to find it and obtain it. The first true example of this plot device appearing in a Hitchcock movie is in The 39 Steps. What are the 39 Steps; just a list of spies names, a detail you don’t know until the very end of the film, and that’s not what’s important. It’s the fact that the bad guys are after it and the hero must find it before they do. Similar McGuffins also factor into the plots of Notorious and North by Northwest as well. Hitchcock even uses a McGuffin as a brilliant misdirection as well, as he does with the money Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) steals in Psycho. Once she is killed off halfway through the movie, the money no longer plays a factor, despite having been a major motivator in the plot so far. Had Hitchcock never defined and popularized the term, we probably would have coined a different, less distinct term for such a thing in movie plots, so we have him to thank for giving these elements a name that is characteristically unique in the way that only someone like Hitchcock could have done.

Alfred Hitchcock was not a horror film director, but he certainly has become a beloved icon of the genre nonetheless. Perhaps it’s because there is an aura of danger and mystery that spans throughout all his films. Apart from Psycho, his intent was never to horrify his audience, but instead to always leave them in suspense. To him, the threat of death was always underneath the surface and it was always his intent to mine that dark side of human existence as a part of the drama within his films. All his movies either involve a plot to kill, or the investigation into a killing, but rarely does he ever indulge in blood and gore. That’s probably why Psycho was so shocking for it’s time, because it was even a stretch for him to take things as far as he did with that film. But macabre themes aside, what has also made Hitchcock revered even to this day is his bold cinematic vision. He was a director in full command of his art-form with enviable support from a major studio. What’s even more remarkable is the fact that he reportedly never put his eye up to the camera itself, trusting he crew completely to capture the image that he had planned for. Numerous filmmakers today, including the likes of Steven Spielberg, Christopher Nolan, Martin Scorsese, and others take inspiration from the unparalleled work of Alfred Hitchcock. With a filmography spanning nearly 50 years, he is one of the most prolific filmmakers ever, and probably without peers in the whole history of the industry. And still to this day, the name Hitchcock remains a household name; still carrying weight in the realms of mystery, suspense, and even horror. His legacy is as well preserved as the Bates Manor House that still sits on the Universal Studios Backlot to this day, nearly 60 years after it was first built. Whether you know him by name only, or from that familiar portly silhouette that he began every episode of his show with, he is an indispensable part of cinema history, and a true Hollywood icon in every sense of the word.