One thing that you’ll notice about the way that the movie industry works is that whenever one brand new idea manages to translate into success, a dozen more just like it will follow in it’s wake. I’ve written about copycat films before here, but another thing that I’ve noticed about the continuous cycle of like minded films that the industry pushes out regularly is that the quality of each film takes a steep decline almost immediately depending on how big the trend is. Usually one big success manages to open the doors for a long in development project that finally has it’s moment to shine, but after a while, it becomes apparent that the industry runs out of fresh properties and ends up scrapping the barrel. And just like that, the craze ends up dying before it’s time should really be up. We’ve seen that happen a lot in recent decades where trends have risen and fallen with great frequency. The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter series beget a whole slew of new fantasy franchises, some good (The Chronicles of Narnia) but mostly bad (remember Eragon; of course you don’t). The dystopian YA craze saw a short life span with the success of The Hunger Games (2012), and it was over pretty much even before the final film in the Games series was released. Right now, the shared cinematic universe craze is seeing a downward slide, with Ghostbusters, Universal’s monster filled “Dark Universe” and the DCEU all failing to capture even an ounce of what Marvel Studios has built for themselves. What the ends of these crazes usually have in common is that they all end by sinking to the rock bottom level with the worst movie that can possibly be made to capitalize on another’s success. That’s certainly the case with the two movies that I am spotlighting in this article; the beloved Lego Movie (2014) and the very maligned Emoji Movie (2017).

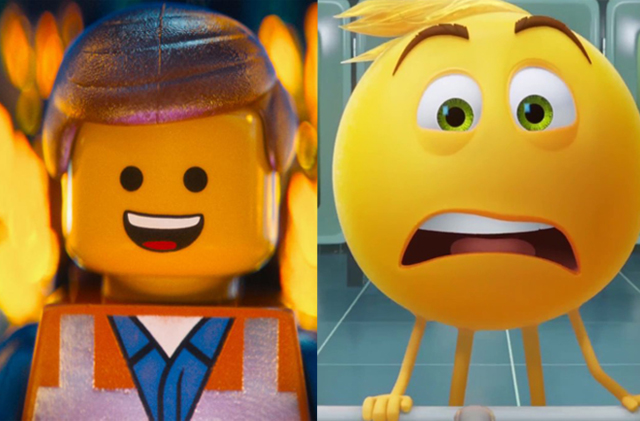

For as long as I have been writing this Tinseltown Throwdown series of articles, this one will mark the biggest disparity ever between the actual movies. There is clearly a victor here and I will say that it is not The Emoji Movie. To show you just how big of a gap exists between these two movies in my opinion, Lego appeared on my best of the year list for 2014, while Emoji topped the worst films of last. There couldn’t be any wider a distance between these movies, and yet they are in many ways linked together. The Emoji Movie’s existence is due to the success of The Lego Movie, as like with a lot of other copycat movies, one studio tries to mimic the other without understanding how they got to that point in the first place. In particular, Sony (the studio behind Emoji) believed wrongly that product recognition was the key to making The Lego Movie popular, so they latched onto one other pop cultural trend that has widespread recognition and exploited that. To be honest, something could have been done with the cultural phenomenon of emoji texts if the filmmakers had any sense of story-telling. They could have made a social comment on the way that texting is creating a shift in human interaction, and a story about Emoji’s could have evoked a deeper meaning of how communication has been broken down into simplistic symbols rather than complex expressions. But no, the movie doesn’t do that; instead it follows a formula that is almost cut and paste from the Lego Movie but without the subtlety or human connection. Essentially, both movies are inter-textual celebrations of their selective products, but while one manages to connect with a soul at it’s center, the other is just a shallow and vain attempt to capitalize on our familiarity with what it’s selling.

“Everything is awesome.”

It can be argued that both Lego Movie and Emoji Movie both derive from a long line of inter-textaul movies, which is a class of film where much of the comedy and drama is derived with the combination of different elements from various types of media. You see this most often in spoof movies, with Mel Brooks and the team of Zucker-Abrams often making fun of many different specific targets like movies, songs, genre cliches, etc. There have been other movies that have also gone the extra lengths to include many different intellectual properties as a part of their story, even when they are from competing companies. Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988) took the unprecedented step of having characters like Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny on screen together for the first and maybe only time. A similar cross platform attempt was made in Wreck-It Ralph (2012), this time with video game characters instead, and while it is brief, the one scene where the title character is in a self-help group with Bowser, Dr. Robotnik, and General Bison was a dream come true for many fans of those games. Steven Spielberg is even mining our sense of nostalgia with his upcoming Ready Player One (2018). But, to make inter-textual reference work, it must be in the service of a relatable story. The Lego Movie managed to do this by making it’s world feel cohesive as a whole, where all these different inter-textual elements co-exist and much of the humor and story is mined from their interactivity. Emoji Movie makes the big mistake of establishing the fact that the characters are aware of their existence and function as part of a phone’s mechanics, and it diminishes their interaction with their own world to just being a showcase for different apps. It becomes clear very early on that all that the Emoji Movie is interested in is selling the viewer on the glorious capabilities that a smart phone has, and it zaps away any power that a narrative may have throughout the film.

“My feelings are huge. Maybe I’m meant to have more than just one emotion! I have so much more.”

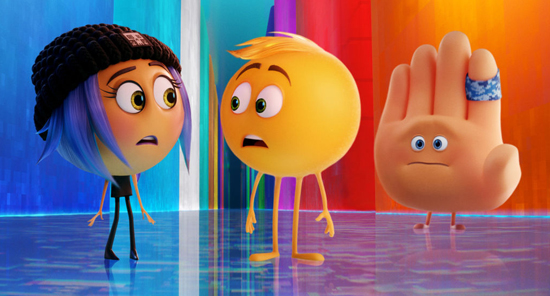

Where The Emoji Movie fails the most is in justifying what it means in the end. Essentially, it falls into the standard “be yourself” narrative, where our main character, Gene the “Meh” emoji (voiced by T. J. Miller), learns to accept that being different from everyone else is not so bad. By itself, this isn’t a bad narrative to go with, but the movie lacks the focus to actually drive that meaning home. In fact, at times it contradicts the notion of individuality, as much of the chaos left behind in this story is a direct result of Gene not fulfilling the function that he was created for. As the movie establishes, Gene is one of many citizens of an emoji community, all of whom are personifications of commonly found emoji’s on your standard phone keyboard. Their daily role is to stand within their select cubicles and be scanned whenever they are selected by their user as part of a text message. Gene’s inability to control his emotions make it impossible for him to be a functional part of the emoji board, so a more sensible direction for the story to go would be for Gene to venture out into the world and learn where his peculiarity may be more at home. But instead, the movie has Gene force the status quo of society to make it so that he can be an emoji that has multiple expressions, which the movie seems to view as a triumph. Isn’t it a little unfair that Gene gets to have a special exception to the rule, which takes attention away from the other emoji’s that have no other expression. In the end, it’s a story that just serves a surface level hero’s journey, without making their hero worthy of any of it. By contrast, The Lego Movie dissects the hero’s journey narrative, by having it’s hero be thrust into a series of events he has no control over and having to tackle the mistaken notion that he’s “special”, when in reality, everyone has that ability to be special within them. In the world of Lego, you could say that everyone is awesome, as long as they show it. Emmet (voiced by Chris Pratt) grows up to be special, while we are supposed to accept that Gene is special and worth supporting. One earns our sympathy, while the other seems forced fed to us.

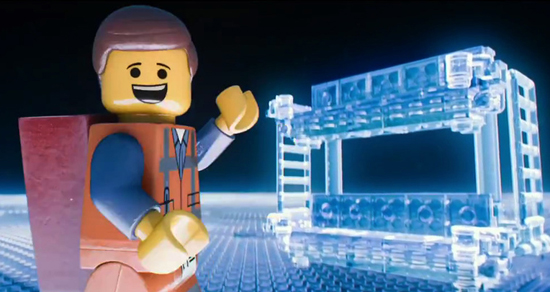

The brilliance behind The Lego Movie is not just in how funny it can make all the pop culture references work, but in how it manages to tie everything together under one underlying theme; the power of creativity. In the world of Legos, the highest honor one can have in life is to be a “master builder”. As the movie establishes, Master Builders can create anything out of the building blocks they find around them and become almost superhero like as a result. In fact, a few master builders actually are superheros, like Batman (one of the film’s most hilarious characters). But Emmet stands out because he follows the instructions rather than creating freely, and this drives a wedge between him and the master builders, who begin to wonder if he really is worthy to carry the load of wielding the legendary “piece of Resistance” (which as we learn is the cap to a tube of krazy glue). This clash of free reign expression and following the rules manifests itself throughout the movie and culminates in the film’s most brilliant scene, as we discover that Emmet and his entire world are really just a construct of a child’s imagination, who’s playing around with his Dad’s intricately assembled sets. The father, played by Will Farrell, treats the Legos with a seriousness that has no room for creative expression, and as we learn, his idea of what the Legos are worth is far different than his son’s. But, the discovery of what his son has built in his playtime opens the father’s eyes to a different understanding, and it establishes what is at the heart of the story; that value of Lego toys is not in the product itself, but in the experience of creating with them, something that bonds different generations together, including a father and son who now have a common love for something fun. The Emoji Movie never makes the case that it’s saying anything more than “aren’t phone apps cool.” The user at the center of the story, a teenage boy named Alex, never once has a connection with the characters that exist within his phone. For the most part, they prove to be an annoyance to him more than anything. It contrasts deeply with how Emmet is connected to the parallel story-line between the boy and his father, because Emmet was selected out of all the toys around him because of the boy’s personal connection with his perceived good-naturedness. The stakes exist, because the boy has imagined a special purpose for Emmet because of how it relates to his own relationship with his father. Emoji Movie never once make us care for the future of it’s characters and that’s where it really falls short.

“I only work in black and sometimes very, very dark grey.”

But, apart from their narrative differences, there is one other thing that drives down the quality of The Emoji Movie, and that’s it’s lack of identity. Upon watching the movie, you can just tell that this was a movie crafted without passion. Every story point is calculated by the demands of a studio that seems to have formulated what a movie like this actually needs. Like I stated before, it’s a movie that wouldn’t exist had The Lego Movie not come before it, and that becomes evident in the way that it just wholesale copies that film in many different ways. Pop Culture references are abound, as is the many different licences that the movie flaunts as a part of their world. But, what Lego Movie manages to do better is to make those different references function as a part of it’s world, and also not be afraid to mock them from time to time as well. Batman doesn’t just make an cameo appearance, he’s one of the central members of the team, and his personality is so exaggerated that he almost becomes a unique personality in his own right, separate from all his previous incarnations. What does The Emoji Movie do? It just has the Poop Emoji show up every now and then just so they can throw in a poop joke to make the little kids laugh (made all the more painful that they dragged an esteemed actor like Patrick Stewart into the role). And even more shameless pull from The Lego Movie comes in the form of how it portrays it’s female lead. Both movies have heroines that have a rebellious side to them, but one has more layers to her personality than the other. As seen in Lego Movie, the character of Wyldstyle (voiced by Elizabeth Banks) puts on a punkish exterior to hide insecurities underneath, and part of her arc in the story is to eventually soften herself to the point where she’s not afraid to share another side of herself to others. The similar character of Jailbreak in Emoji Movie (voiced by Anna Faris) takes a similar character design, with black hair and clothing, but has none of the depth to match the personality. She’s dressed that way, because she no longer wants to be a princess emoji, and that’s it. It’s a very surface level form of personality and makes her feel so uninteresting by comparison. The same can be said about the rest of Emoji Movie, as it becomes clear that there was no attempt to find any depth in the story. The Lego Movie’s creators, Christopher Miller and Phil Lord, clearly opened up their toy box with the intent to have some fun with it, and the fact that they found deeper meaning in it all was just icing on the cake. Emoji Movie is just there to be a product.

Which gets us to probably the most infuriating aspect of The Emoji Movie, which is the shameless way that it shills for other products. Essentially, the movie’s story-line has it’s characters moving from one phone app to another, never once endearing us to their journey and instead just uses the different changes of scenery as a mini commercial for each selective app. This should be evident right from the moment that the characters stumble into a “Candy Crush” game, and it just gets to be infuriatingly self indulgent once they enter a “Just Dance” sequence. There is no commentary given to any of the different places they visit; all it essentially says to the audience is “Hey let’s check out YouTube, or let’s find our way to Dropbox, or isn’t it lovely here in Instagram.” The script for this film might as well have read “place your ad here” over and over again. And a movie like this needn’t be a feature length commercial, as The Lego Movie has demonstrated. Lego had to prove a lot of naysayers wrong when it first went into development, as on the surface it too would have appeared to have been nothing but a feature length commercial for a singular product. But, with it’s heart in the right place, and direction from Lord & Miller that actually utilized the potential of such a premise, The Lego Movie managed to make us forget about the commercialism behind it and instead allowed us to enjoy it as a film in it’s own right. It became first and foremost a movie, and the fact that it was tied to a product was irrelevant. The Emoji Movie sadly doesn’t understand that and it instead tries to mask it’s narrative shortcomings with unending reminders of it’s commercial origins. With that, it can’t hide it’s soulless identity as just a tool for consumerism, delivering the idea that the more vibrant a collection of apps and emojis, the livelier the world will be. The Lego Movie’s miraculously manages to honor the appeal of Lego toys, without ever forcing a consumerist intent on it’s audience. Lego’s popularity speaks for itself, and the movie never tries to assume otherwise, nor force it down our throats.

“Nobody leaves the phone. Delete them.”

The Lego Movie managed to perform a magic trick of escaping the perceived commercialism of it’s premise, and surprise all of us with it’s potent and surprisingly heartfelt story. The Emoji Movie just ended up being exactly what you thought it would be, and in some ways even worse. For one thing, the only quality thing about The Emoji Movie is the animation used to bring it to life, which makes it doubly insulting that it’s used on something so crass and soulless. Emoji is built upon a studio mandate which lacks all vision and is created just to spotlight the different brands that paid to be seen within this movie. The fact that it is marketed towards kids is even more insulting, because it teaches them no worthwhile lessons, and instead drives younger people to be more attached to their phones. The idea that the climax of the movie hinges on the teenage boy communicating through the ideal emoji on his phone, instead of you know going up to a person and talking to them in person, is a clear sign of the wrong kinds of values we should be promoting in our culture right now. The Lego Movie is commercial too, but it does a great job of making us forget that and just enjoying the story it wants to tell. It’s characters are also more appealing and have worthwhile arcs to their stories. But, where Lego truly shines is in the fact that it touched upon universal meaning in it’s message. The story is essentially about people coming together through shared interest, and the fact that it’s through Lego toys is beside the point. There’s nothing more satisfying than seeing a father and son grow closer together as they play with their Legos, and teach each other the value of creativity and unity through that experience. That’s where Lego Movie found it’s heart, and what Emoji Movie clearly did not understand. In the long run, Emoji Movie represents the pitfalls of trying to capitalize on a craze, because the choices of how to sell a movie eventually begin to overwhelm the choices in the making of a movie, and Emoji had no intent on ever being it’s own unique thing. As Lego Movie states, “Everything is Awesome,” but Emoji Movie is far less so.

“You don’t have to be the bad guy. You are the most talented, most interesting, and most extraordinary person in the universe. And you are capable of amazing things. Because you are the Special. And so am I. And so is everyone.”