One of the most common titles that you’ll see in many movies is that of writer/director. What normally can be two jobs held by two different people on any given movie will also sometimes be a role held by a singular person. And as is the case with writer/directors, they are far more in command of the film’s narrative and vision. We see a lot more people today that direct films from their scripts; some of whom I have spotlighted in this series. And it is true that film directors have existed throughout Hollywood history that often wrote the screenplays themselves. The only difference today is that the writer/director was less commonplace in old Hollywood than what we see in the film industry today. There were some noteworthy directors who wrote the bulk of their own filmography. There was John Huston, Preston Sturges, and of course Orson Welles (though his authorship of the screenplay of Citizen Kane is challenged somewhat, as many believe it was mostly Herman Mankiewicz who wrote the bulk of that movie). But, there hasn’t been a filmmaker before or since who mastered both crafts of scripting and directing with such versatility and with his own unique voice intact as Billy Wilder. Wilder was unlike most other double threat filmmakers, as he carved out his own cynical, satirical voice while working in so many different genres. He effortlessly went from making film noir, to psychological drama, to hard boiled political satire, to elegant romance, to wacky screwball comedy without losing that special Wilder touch. That’s why even in today’s Hollywood he’s celebrated as a true original, and he remains one of the most consistently successful filmmakers of any era. What is also interesting is that he managed to create movies with a distinctly American sensibility, both in his movie’s sense of humor and their observations of American society; a remarkable achievement considering his immigrant past and the fact that English was his second language.

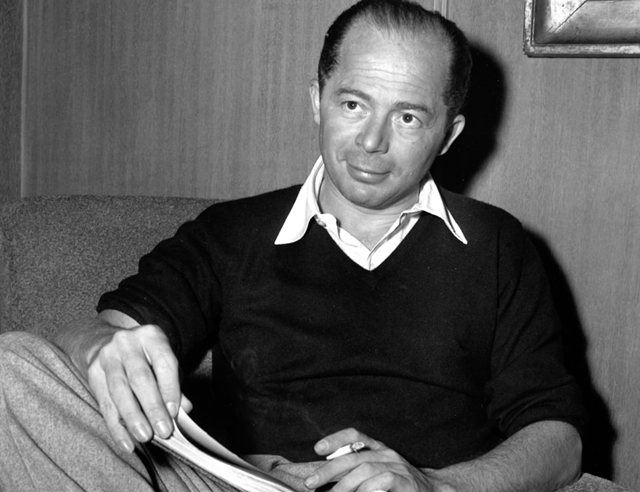

Samuel Wilder was born in Austria-Hungary in 1906 to a Polish Jewish family just outside of Vienna. His family moved around a lot, including a brief time in New York City, which left an indelible impression on him as his latter career would attest. As he grew older, he sought a career in journalism, with a special interest in the field of entertainment. He found himself visiting night clubs everywhere between Vienna and Berlin interviewing jazz musicians and the like. Unfortunately, the rise of Nazism in Germany and Austria forced Billy Wilder to relocate. He settled in Paris, where for the first time he was commissioned to write for the movies. He contributed a number of screenplays to many films made by his fellow German ex-pats as they were in their Parisian exile. In that time, he also got to make his debut as a director with the French language film Mauvaise Graine (1935), which he also wrote. However, as Nazi occupation of France inched closer, Wilder knew he would have to uproot once again. Thankfully, by this time, Hollywood finally came a calling, as he was granted the chance to write the screenplay for Ernst Lubitsch’s next comedy, Ninotchka (1939). Billy Wilder’s brilliant comedic mind translated perfectly into Hollywood and his work on Ninotchka was wildly celebrated; a film that famously was sold on the tagline “Garbo Laughs,” a reference to the out of character turn in the movie from the mostly stoic Scandinavian leading lady at it’s center. Building off of that success, Wilder would go on to have one of the most successful runs of any filmmaker in Hollywood, both as a writer and director. His filmography is full of movies that are still celebrated as essential American classics, like Double Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), Sunset Boulevard (1950), Ace in the Hole (1951), Stalag 17 (1953), The Seven Year Itch (1955), Some Like it Hot (1959), and The Apartment (1960). And while all his films are very different in tone and subject, they nevertheless feature the same distinctive voice that was unmistakably his own; which was often slick, irreverent, and sharply critical while at the same time maintaining a sense of playfulness. So, let’s take a look at what made the movies of Billy Wilder the works of cinematic wonder that they are.

1.

LUST & GREED

If there was ever a common thematic element found throughout the movies of Billy Wilder, it would be these human failings. The characters within Billy Wilder’s movies are often motivated to do the dark deeds that they do by one or the other, or even both. The movie Double Indemnity, one of the films scholars cite as one of the grandfathers of Film Noir as a cinematic style, is a movie where both sins come into play within the narrative. Fred McMurray’s Walter Neff falls under the seduction of lonely housewife Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck), who sees an opportunity to scam the insurance company that Neff works for while also getting rid of her husband, thanks to knowledge of the double indemnity clause in her husband’s insurance plan that Neff clues her into. In the movie, Wilder explores the depths that people will go to satisfy their greedy intentions while at the same time falling under their lustful inclinations against their better judgment. Wilder liked to explore this aspect within the human condition, how desires cloud our better instincts and often lead to ruin. While Double Indemnity takes a salacious and dark view of the complications of dark desires at play, he also knows how to make fun of society’s underbelly when it comes to seeking power and sexual gratification. The film The Apartment also takes a look at scandalous behavior behind the veneer of “normal” domestic life, but does so with a bittersweet sense of humor as well. To get ahead in life, C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) lends him apartment to his bosses from work so they can have their extramarital affairs in secret, until he suddenly finds himself in love with one of the girls caught up in the affairs, Fran Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine). Here, Wilder finds sweetness in the same kind of story that more often would turn sour in the past, showing that he could indeed tackle the same thematic elements with a great amount of nuance and intelligence. More importantly, in both cases, he’s confronting the fact that both lust and greed are very human traits that often carry a degree of consequence for his characters, and he’s allowing the audience to confront these same issues to in a way that was quite daring in Hollywood for that time.

2.

DIFFICULT MEN . . . AND WOMEN

Billy Wilder had a special knack for creating iconic characters that go on to become among the most famous in movie history. But what also makes his characters interesting is the fact that most of them are very much morally compromised. Most of his characters fall very much in the moral gray zone, and there are genuinely very few pure souls in his movies. But it seems he especially is interested in the most depraved characters of them all; the ones who have fallen off so sharply that there is no hope for redemption for them in the end. He seems to find these characters the most fascinating, because their falls from grace are often when his satirical voice finds it’s sharpest edge. More often than not, his flawed characters are men who grow increasingly corrupt as the movie goes along, but he has also created fascinating female characters that also ride that moral line in the darker shadows. Phyllis Dietrichson for instance can be viewed as one of the original femme fatales of American cinema. Particularly in his earlier films, it’s hard to find a person to root for, as pretty much all of his characters have some irredeemable flaw. In Sunset Boulevard, we hear the story from the point of view of William Holden’s Joe Gillis, who as we learn ends up exploiting the connections of a delusional aging movie star named Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) to get himself ahead, only to find out too late that Norma’s delusions drive her to enact bloody revenge. One predator falls victim to his prey once she feels betrayed. That’s a common thread in Wilder’s movies; bad people trying to overcome the situations they got themselves into with worse people. And then there are the characters whose spirals are predictable and the story becomes awaiting to see how far they will go before the fall. In the ahead of its time Ace in the Hole (1951), Kirk Douglas plays Chuck Tatum, a sleazy journalist who exploits local tragedy for his own gain, until it turns into a literal circus. We know that a man as bad as him will eventually meet his fall, but the harsh indictment that Billy Wilder makes, as he does in most of his movies, is showing just how far society is willing to indulge the bad behavior of these characters.

3.

MARILYN MONROE AND FRANKNESS WITH SEXUALITY

If there was one thing that especially marked Billy Wilder’s career in the latter half, it was way that he turned Marilyn Monroe into a cinematic icon. Ms. Norma Jean was already well known for her musical comedy work like Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) and How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), but it was once she began to work with Billy Wilder that she catapulted to the height of her onscreen career. You know that iconic moment where her skirt is blown up by the updraft of a subway vent, the most famous image of Marilyn Monroe that is replicated everywhere? That was from Billy Wilder comedy called The Seven Year Itch. Indeed, Wilder was able to get the best out of Monroe, far more than any other filmmaker had before or after, and that is most evident in what was their most celebrated collaboration; the screwball comedy Some Like it Hot. Monroe gives without a doubt her best and most effervescent performance in that movie, and it’s the one that absolutely plays to her talents the most. She of course excels in the musical numbers, but her ability to handle the comedy is also admirable, especially working with heavyweights like Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon. The movie itself is also one of the best examples of another trait of Wilder movies; the more open, frank discussions of sexuality in film. Though Wilder still worked within Code era guidelines, he was able to address sex in a more frank and direct way that few other filmmakers would even dare to address. The extramarital affair at the heart of Double Indemnity is evidence of that, as is Sunset Boulevard’s implied sexual history with regards to it’s two leads. In Some Like it Hot, sexual attraction is a major part of the plot and humor. And long before it was acceptable in society, Some Like it Hot even addresses same sex attraction, as Jack Lemmon’s cross-dressing character becomes the object of affection for a rich playboy (Joe E. Brown). Even when confronted with the information that the woman he adores is really a man in drag, Brown delivers the now immortal phrase, “Well, nobody’s perfect.” Only Billy Wilder would dare to put that in his movie and get away with it, and Some Like it Hot is now celebrated by LGBTQ fans for it’s groundbreaking stance, even if it’s played up for a laugh. It’s one of the most endearing parts of Billy Wilder’s filmography; not being afraid of addressing underlying issues of sexuality in society in an honest fashion, while also solidifying and legitimizing Marilyn Monroe as an icon, something that the gays are also grateful to Billy Wilder for.

4.

AMERICA UNDER A MICROSCOPE

Billy Wilder was often viewed as a cynical man based on his movies, though that can be a misleading thing to characterize him with. What ended up leading many to this conclusion is the fact that he often didn’t give his characters a satisfying conclusion in the end. There is no redemption for his flawed characters; no riding off into the sunset for his heroes. Often, his characters end up dead or in prison by the end of the movie, or in William Holden’s case in Sunset Boulevard, dead from frame one. But, he doesn’t share these bleak endings as a comeuppance alone for his characters sins. Often these characters are caught up in societal evils that they willingly participate in, but only too late learn the perils that they have put themselves into. The descent of Norma Desmond is a particularly potent example of Billy Wilder indicting a segment of society; ironically the one that took him in during his wartime exile, Hollywood. In Sunset Boulevard, we see the madness that Norma Desmond has fallen into, living within this delusional bubble inside her Beverly Hills mansion, but there is a sad reason for her isolation. Hollywood has deemed her too old to be relevant anymore, but she’s too stubborn to accept that unfair reality and it sinks her even deeper into madness, something that Joe Gillis shamefully exploits. There is few indictments of Hollywood as harsh as the closing of Sunset Boulevard, as Norma poses for her “close-up” as she’s being dragged to the asylum, having lost all touch with reality and can only react the only way she knows how, by performing for the camera. It’s not the only thing that Billy Wilder examines with a sharp satirical eye in his movies; Ace in the Hole examines sensationalized tabloid journalism, Double Indemnity looks at the greediness of insurance brokers, and The Apartment takes a stab at soulless corporate culture and the sexual harassment that arises from it. Wilder would have examined these assets of society no matter what country he was making movies in, but he especially found America fertile ground for finding these darker aspects of society. He was by no means anti-American; he remained a grateful émigré to the United States and lived out the rest of his days here, thankful for the creative freedom it gave him. But, he was also not afraid to call out the darker sides of American culture in his movies, and that made him a very crucial and fearless voice in Hollywood for many years.

5.

SHARP WITTED DIALOGUE

It’s hard to believe that Billy Wilder didn’t speak a word of English before the age of 10. Circumstances of world politics led him to come to America in his latter years, but German still remained his first language. So it is amazing that his screenwriting style feels so attuned to an American sensibility. His sense of humor and style of writing, which he cultivated during his years of covering Jazz club life in pre-War Europe, translated into English without losing any bit of wit in the process. He managed to capture the language of American culture perfectly once he settled into Hollywood. Just listen to the frantic paced back and force exchanges in Double Indemnity, innuendos and all. Billy Wilder could write in English better than most native born speakers who were writing movies around the same time, both in quantity of dialogue and in quality. Sure, he had co-writers through much of his career, such as Raymond Chandler (Double Indemnity), Charles Brackett (Sunset Boulevard), and I.A.L. Diamond (The Apartment), but if you listen to him in any of his late career interviews, as he speaks in that charming Austrian accent that he never quite lost, a lot of the wit of those movies definitely came from him. He had a knack for writing character interactions with dialogue that sounded natural yet still clever when you listen closely. From the Code challenging sexual tension of Double Indemnity, to the charming small talk in an elevator ride from The Apartment, he could write any kind of mode for his stories. Not only that, but he’s responsible for some of the most quoted final lines in movie history, like Norma Desmond’s “Alright Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up,” to Fran Kubelik’s perfectly succinct, “Shut up and deal,” to the already mentioned iconic and daring closer of Some Like it Hot. It’s a testament to Wilder that he also exceled behind the camera as a director, because he could have stayed a screenwriter and still would have been considered one of the greatest of all time. The fact that he was a master of both crafts really cements him as a Hollywood legend, and probably one of the best examples ever of what it means to be a writer/director.

One of the best things about Billy Wilder’s life and career is that he endured long enough to benefit from the impact that his movies had on Hollywood. He passed away in his home in West Los Angeles at the ripe old age of 95 in 2002. Though he hadn’t made a movie since the 1980’s, he still maintained a presence in Hollywood, being a vital bridge between old and new Hollywood. Though he became a naturalized American citizen over the years, he nevertheless held a special place in his heart for the home he left behind. One of his last cinematic contributions was offering uncredited script contributions to a project he hoped to direct one day called Schindler’s List (1993). Ultimately he passed on directing, believing himself too old at the time and not a good fit in the end, eventually leading to Steven Spielberg taking on the project. Still, Billy Wilder was instrumental in getting Schindler’s List off the ground and he remained slightly involved in helping Spielberg shape the final story. It was important for him to be a part of the movie, because he himself lost family members to the Holocaust, and he felt this was his way of honoring them after so many years. One of the benefits that he probably had in his long lived life was seeing how so many filmmakers aspired to make the same kinds of movies that he made; especially when it came to the more subversive stuff. In his whole career he managed to spark the beginnings of film noir, helped to shed a light on the darker aspects of cultural institutions like Hollywood, the media, and capitalism itself, and even pushed the boundaries of sexuality for his time. What he left behind were what many consider to be among the best films in cinema history, and it is astounding how varied all of them are as well, ranging across multiple genres. He was recognized in his time for his cinematic contributions, with The Lost Weekend and The Apartment both taking home Best Picture in their respective years, as well as Directing and Screenwriting honors for Wilder. But the real reward for his long career is how well his movies hold up even today. Some Like it Hot still gets a laugh, Sunset Boulevard still manages to be chillingly relevant, and Ace in the Hole is eerily prophetic in it’s account of what the media would end up turning into. Few can command the roles of writing and directing a film with equal measure, and Billy Wilder is one of those few that really made Hollywood what it is today, and he’s got the sharp-witted iconic masterpieces to back that up so many years later.