The start of the Summer Season is quickly becoming the domain of Marvel Studios. Just like how Will Smith once dominated the Fourth of July weekend during the late 90’s, or how Memorial Day weekend was once traditionally owned by the Star Wars franchise, Marvel’s track record of late has allowed them to become the most reliable team necessary for kicking off each summer in a big way. Each of the Iron Man films have claimed this weekend, as well as most of the Spiderman movies, and of course, the Avengers who broke all sorts of records upon their opening release. Now, Captain America is given the prime spot, with this the third entry in his successful standalone series. It was also a release date that they had to contend for. Warner Brothers and DC had already staked a claim on this weekend for their big new release, Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, but Marvel, perhaps in one of the most blatant alpha dog moves we’ve ever seen play out in Hollywood history, claimed the spot as well and dared DC to challenge them for it. Eventually, DC relented, probably sensing the increasing influence that Marvel now holds on the industry, and Batman v. Superman was bumped up two months into a mid Spring release. Of course, having now seen both, it’s pretty clear why both DC and Marvel made the moves that they did. The movies are surprisingly similar in both concept and theme, but what really ends up setting them apart is the execution. The consensus now is that Batman v. Superman was in all respects not a good film. Sure, there were good things in it, but the overall sum of it’s parts ended up being a convoluted mess. Civil War on the other hand takes the same kind of story and delivers it much better.

Civil War benefits from the already solid foundation that has proceeded it in all the previous Marvel films leading up to now. At this point, audiences understand that everything in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is connected and that we are basically here to watch what’s essentially a new episode in an ongoing series. This is what was lacking in what DC did with Batman v. Superman. DC is rushing itself into the prospects of having their iconic characters share screen-time together, without the foundation to support that venture. The image of Batman and Superman together alone is pleasing, but without having time invested in understanding why they are together, the meeting has no weight. DC, and more pointedly Zack Snyder, are just throwing things together without purpose. Marvel has now made a dozen films leading up to Civil War, and it’s only the beginning of a build-up to something bigger. Essentially, we are at the point now where we know who these characters are and what makes them tick, and the interactions between them are what drive the story. This allows Marvel a little more leeway in presenting the stories they want to tell, because everything is driven by the personalities of their characters as opposed to being forced to fulfill certain obligations of the plot. The Marvel films never feel forced, and that’s why audiences love them. With Civil War, Marvel is given the opportunity to tackle one of the most intriguing story angles available to them, and that’s what happens when the heroes turn against each other.

Captain America: Civil War takes place in the immediate aftermath of Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015). Captain (Chris Evans), Tony Stark/ Iron Man (Robert Downey, Jr.), Black Widow (Scarlett Johannsen), Falcon (Anthony Mackie) and War Machine (Don Cheadle) are called to the Pentagon by General “Thunderbolt” Ross (William Hurt) after a failed mission in Nigeria causes significant collateral damage. Ross tells the Avengers team that the United Nations has drafted a new law called the Sakovia Accords (named after the tiny nation that was destroyed by Ultron) which mandates that the Avengers must submit to oversight by the multinational body instead of functioning independently. The plan receives a mixed reception from the heroes, with some being for the plan (including a guilt racked Stark) and others being against it (especially Captain, who distrusts government agencies after the fall of SHIELD in The Winter Soldier). Things get more complicated when a terrorist attack disrupts the passing of the Accords bill, with the prime suspect being The Winter Soldier (Sebastian Stan). The hunt is on for the suspect, but Captain (who was friends with the Winter Soldier back in the War years) believes he might have been framed, so he hopes to get to him first. Unfortunately, another disguised vigilante is on the hunt too; T’challa (Chadwick Boseman), the king of the African nation of Wakanda, who takes on the guise of Black Panther. Unbeknownst to everyone, the strings of this plot are being pulled by a vengeful mercenary named Zemo (Daniel Bruhl) who seeks to split the Avengers up and have them destroy one another. Captain tries to search for answers and save his friend, but Iron Man develops a coalition of his own to stand in his way, which includes new allies Vision (Paul Bettany) and Spiderman (Tom Holland). But, Captain receives assistance himself from Hawkeye (Jeremy Renner), Scarlet Witch (Elizabeth Olsen) and Ant-Man (Paul Rudd) and this all leads to an inevitable Battle Royale between all of our favorite heroes.

As you can tell, this is a pretty jam-packed film, but what makes it so pleasing is the fact that Marvel knows how to maintain a balance with all it’s story elements. They’ve gone through two Avengers flicks already, so now it’s elementary for them to have a movie with a cast this big. It’s any wonder why they didn’t just call this another Avengers film anyway, since all of them are here minus Thor and The Hulk, who will be appearing together in the upcoming Thor: Ragnarok. At the same time, I can see why the Civil War story-line was given over to the Captain America franchise. This movie is a logical continuation of Captain’s own story arc, as the optimistic, patriotic superhero is having to re-adapt to a changing political world that no longer has clear-cut good vs. evil alliances. The Captain America movies are the most politically charged ones in the Marvel Canon, and Civil War is no exception. The movie touches on political themes like the necessities of regulation versus individual freedom, as well as more universal issues like the corrupting power of vengeance. In this story, the heroes are confronted with the idea that they may be doing more harm to the world than good, and that things may better if they weren’t working together. It’s a movie that is much more than just watching heroes fight; it’s got a philosophical underline to it that helps to make the stakes much more relevant to us. That’s what Batman v. Superman lacked; the moral dilemma that drove these heroes apart. Civil War is also much more focused on it’s purpose than it’s DC counterpart. The characters aren’t just posturing for dominance. In fact, they spend much of the movie trying to avoid fighting each other and they try to resolve their differences peacefully. It’s only when things go horribly haywire that they finally come to blows.

And, without a doubt, that ultimate confrontation is the highlight of the film. When Team Captain and Team Iron Man trade blows near the end of the second act, it becomes one of the absolute best things that Marvel has ever put on screen. What I love so much about it is the fact that the scene plays upon all the strengths of the characters. Everyone’s super powers give them advantages over some participants, while at the same time they create disadvantages against other participants. Spiderman’s web-slinging for instance gives him an advantage over air based opponents like Falcon, but his lack of physical strength makes his fight against Captain more of a challenge. The verbal barbs they throw at each other are also entertaining, especially between Black Widow and Hawkeye (“We’re still friends right?” “Depends on how hard you hit me.”). And Ant-Man nearly steals the scene alone when he takes full advantage of his powers. It’s a brilliantly executed scene that manages to take full advantage of the potential of the situation. Every interaction is creative and well executed, and it will probably answer many comic book nerd questions about who would win in a one-on-one fight. That being said, the movie wisely doesn’t let the scene get out of hand, and the focus remains squarely where it should be, and that’s on the opposing conflict between Captain and Iron Man. The plot centers around these two, as it should, and the rest thankfully doesn’t feel like a distraction or filler. I especially liked how they handled the smaller story arcs; such as Vision trying to learn his place in the world, Scarlet Witch doubt her own existence, and especially the coming of age arc that Black Panther goes through, which perfectly compliments the theme of vengeance in the movie. Once again to compare, Batman v. Superman seemed more concerned with filling screen-time with a mish-mash of action scenes followed with fan service, and none of it melded together. In Civil War, everything is given a causality and a consequence and that makes all the different elements feel more cohesive as a whole.

The reason Marvel is able to make these huge casts work so well is because they’ve allowed their library of films to build the necessary groundwork for these character’s motivations beforehand, which allows Civil War to feel like a more natural progression of these character arcs. This has been greatly helped by the performers, who not only take their roles seriously, but also seem to embody every aspect of these characters on-screen and off. Chris Evans continues to prove exactly why he is the perfect choice for Captain America, filling him with both wide-eyed innocence and the strength to never give up. Robert Downey Jr. of course is the embodiment of Tony Stark, swagger and all, and though he’s a little subdued here, he’s still endlessly charming, especially in his brief scenes with young Spiderman. Speaking of which, one of the best parts of this movie is the new re-imagined Spiderman. After finally getting the character back from Sony, Marvel is able to relaunch the character their way and this may be the closest we’ve ever gotten to the having the character exactly as he’s portrayed in the comics. Not that Tobey Maguire or Andrew Garfield were terrible (despite their lackluster movies), but Tom Holland’s Spidey is exactly what he should be and that’s an upstart kid trying to find his way in the world. It’s great that Marvel is now finally able to explore that angle with the character and he’s a great addition here. Chadwick Boseman’s Black Panther is also welcome, and his performance as the character makes you eager to see what more will be explored when he gets his own film next year. The biggest surprise however is Daniel Bruhl as Zemo. This is a very different take on the character than we’ve seen before (sorry comic fans, no purple sock mask this time) but it’s one that surprisingly fits this film very well. He’s a normal person with no powers, and yet with undying vengeful fervor and a well laid out plan, he’s able to take down a team of super heroes without ever getting caught in the crossfires. It’s a very different kind of villain for Marvel and it made sense to have him be behind all this. Actor Daniel Bruhl’s understated performance also works really well here too. Given how Captain’s rouges gallery has been pretty weak thus far on screen, it’s nice to see this film utilize one with complex motivations and a dangerous death wish mission that feels shockingly real.

But, despite all the movie’s strengths, I do have some minor nitpicks that prevent this from being an outright masterpiece. For one thing, I felt that the visual style of the movie felt a little flat. Not that the movie looks horrible; it’s just that it felt uninspired, like the filmmakers didn’t make any effort to let the visuals stand out. There are some nice visual touches here and there, but the overall aesthetic feels very weak. The first two Captain America films featured very drastically different aesthetics; The First Avenger (2011) was glossy and colorful, invoking Wartime films of the 1940’s, while The Winter Soldier (2014) was washed out and gritty, like spy thrillers of the 60’s and 70’s. Civil War is not a huge artistic jump from The Winter Soldier, remaining effectively very similar visually, so maybe I’m being a little too critical expecting something different, but even still, it was a visual choice that I felt was wasted on this film. The only other thing that I want to complain about is some of the pacing. The film has definite highlights to be sure, but there are stretches where the constant globe-crossing done by the characters prevents the plot from gaining any traction. For the most part, it’s not distracting, but the biggest pacing issue comes in the third act. This is mainly due to having the best scene in the movie, the Civil War fight itself, not being the climax of the story. That scene is so good that it overshadows everything that comes after, and that becomes a problem. Not that what follows is necessarily bad; it’s just anti-climatic. The movie unfortunately feels like it’s deflating for the remaining 25 minutes up until the credits, and that’s an unfortunate way to go out. Even still, the movie still takes some nice dark turns in the last act, and has a decent fight scene, but it’s an ending that doesn’t sustain itself as well as it should’ve given the high bar that had been crossed before it. But, none of this makes this a bad movie by any means, and it’s overall a very well executed movie. It just has some unfortunate blown opportunities that can’t be ignored.

I would still highly recommend this movie to any Marvel fan out there who’s probably going to be watching this anyway. All comic fans in general will like this to be honest. Is it the best Marvel movie ever made? It’s one of the better ones to be sure. It hasn’t replaced Guardians of the Galaxy as my personal favorite, because that 2014 film is the one Marvel movie that I felt transcended it’s place in the genre as well as in the Marvel Canon and became a classic on it’s own. Civil War is without a doubt the best we’ve seen from the Captain America franchise, and it actually works as a better Avengers sequel than Age of Ultron, though I’m still fond of that movie too. As a piece of the MCU puzzle, it’s perfectly acceptable and the places it leaves our characters at by the end opens up many exciting opportunities going forward as Marvel gears up it’s Phase 3. The one thing that is without question, however, is the fact that this is how DC should’ve made Batman v. Superman. Unlike that film, Civil War actually gives motivations to it’s characters and a moral dilemma that is much more believable. One wishes that Batman and Superman actually had something worth fighting for other than to gratify their egos, and that their fight wasn’t so forced on us by a studio mandate. Marvel made Civil War a natural progression of their larger story-line, and it’s great to see that nothing story wise was wasted. Though some of the visual and tonal shortcomings do rob the film of some of the power that it could have otherwise had, it’s still endlessly entertaining. It also shows that Marvel still hasn’t lost it’s edge, and hopefully they continue to deliver strong in the remainder of their Phase 3, which includes the returns of Spiderman, Ant-Man, an origin story for Black Panther, as well as the introduction of Doctor Strange to the universe. There may be no victors in this Civil War for the Avengers, but Marvel has clearly shown both DC and Hollywood who’s the winner, and let’s hope these winners continue to deserve their victory.

Rating: 8.5/10

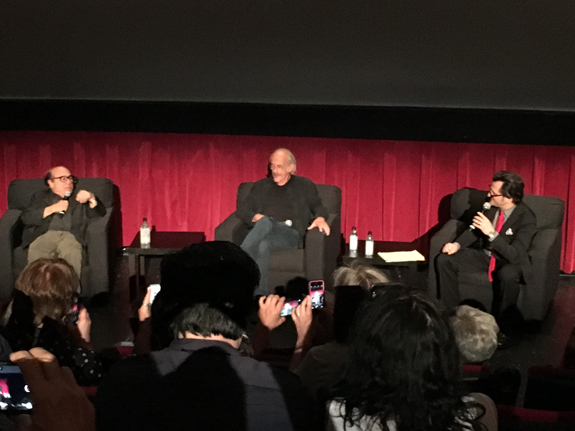

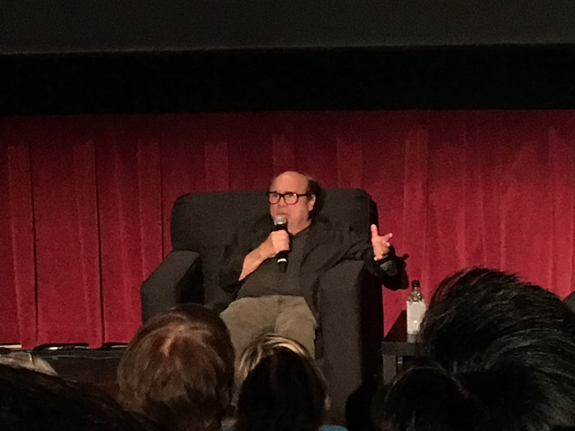

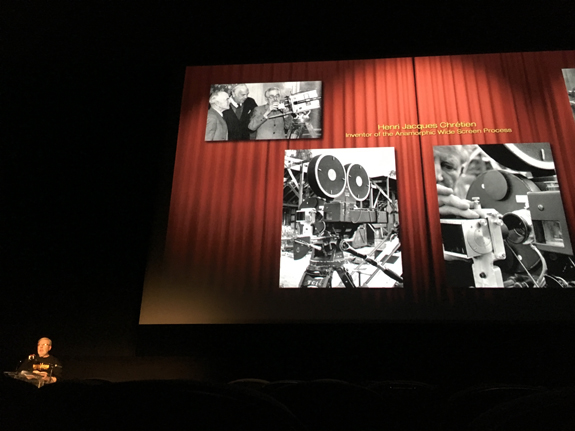

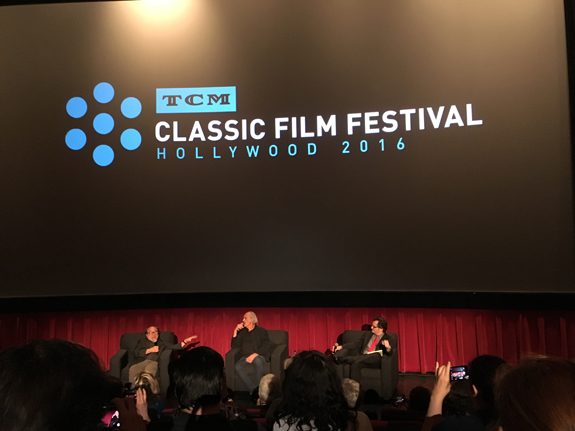

The interview gave us a interesting look into the making of the movie, especially with regards to director Milos Forman’s sometimes unusual tactics. They mentioned that the hospital was a real working one that had authentic mental patients that Forman strongly encouraged his actors his actors to interact with, in order for them to gain more insight into the conditions that their characters are dealing with. The two of them also talked about their experience of working with Jack Nicholson, which could sometimes be an adventure in itself. Naturally, DeVito did most of the talking during the interview. Lloyd maybe said no more than five words total during the interview. Not that it was a bad thing; showing up in the first place was more than enough for him to do to make this showing worthwhile, in addition to Danny DeVito being there. This was a nice highlight for this festival, and one that the festival runners managed to make happen at the last minute; the interview portion wasn’t listed on the programs, and the only way people could know about it is if they followed the festival on social media. Thankfully, I managed to learn about it and work it into my festival schedule. It’s a treat when you can hear about the film from the actor’s perspective, and here we got two from some genuine legends.

The interview gave us a interesting look into the making of the movie, especially with regards to director Milos Forman’s sometimes unusual tactics. They mentioned that the hospital was a real working one that had authentic mental patients that Forman strongly encouraged his actors his actors to interact with, in order for them to gain more insight into the conditions that their characters are dealing with. The two of them also talked about their experience of working with Jack Nicholson, which could sometimes be an adventure in itself. Naturally, DeVito did most of the talking during the interview. Lloyd maybe said no more than five words total during the interview. Not that it was a bad thing; showing up in the first place was more than enough for him to do to make this showing worthwhile, in addition to Danny DeVito being there. This was a nice highlight for this festival, and one that the festival runners managed to make happen at the last minute; the interview portion wasn’t listed on the programs, and the only way people could know about it is if they followed the festival on social media. Thankfully, I managed to learn about it and work it into my festival schedule. It’s a treat when you can hear about the film from the actor’s perspective, and here we got two from some genuine legends.