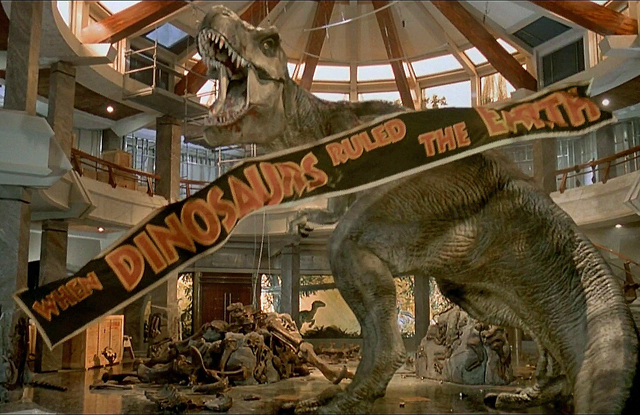

The Fourth of July weekend has commonly been a strong one for summer movies. Amid all the barbecuing and the fireworks, a good helping of American moviegoers also fit in a trip to the cineplex as well, and Hollywood usually reserves that time slot for some of their biggest attractions. While the summer season usually sees successful releases for films of all kinds of genres, it’s usually the the action flick that rules the Fourth of July weekend. Whether or not that’s a reflection of the holiday spirit or the kind of “rah-rah”, guns-blazing patriotism that comes along with the celebrations is uncertain, but it’s definitely the common pattern of the holiday weekend at the movies. In the past, we’ve seen this time frame dominated by the likes of Transformers (2007), The Amazing Spiderman (2012), Men in Black (1997), and the appropriately titled Independence Day (1996). And given that movie studios spread out their releases over a long weekend frame during the holiday, this is also a time of year where new movies are given a longer head start, making it to theaters on a Wednesday as opposed to the traditional Friday. All this to show that the Fourth of July is a marquee date on the calendar for Hollywood. This year, we are seeing a very strong summer season with movies like Avengers: Age of Ultron, Inside Out, and Jurassic World all holding very strong beyond their opening weekends. Competition in this field is tough, which is why Paramount is hoping their big Fourth of July release can live up to the legacy that this weekend usually holds. And what better way to celebrate the founding of America than an action flick sequel starring an Austrian born former state governor.

Terminator: Genisys is the fifth entry in the long running Terminator franchise. Though the Terminator series started off strong in the 80’s with the now iconic original film, and was made even more legendary by it’s amazing sequel, Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1992), it has since struggled to find it’s direction with all the subsequent titles released thereafter. Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (2003) was a largely forgettable cash-in, and Terminator Salvation (2009) took a clever and interesting concept and ruined it with a poor execution. Terminator: Genisys marks the latest attempt to revitalize the series and update it for the times we now live in. The movie has one thing in it’s favor; it marks the return of franchise star Arnold Schwarzenegger, who’s slipping back into the familiar territory of action flicks now that his years in politics are over. It certainly is one of the movie’s best selling points, because beyond that, this film is a hard sell. Relying heavily on it’s brand name and the star power of the Governator, Terminator: Genisys unfortunately tries way too hard to squeeze out any last ounce of substance in this franchise. The same can be said about the last couple Terminator movies as well, but it feels much more apparent this time around given the way that the story goes. Here, instead of moving the plot forward in time, we are taken back to the beginning and are shown the world of Terminator thrown into disarray. Terminator: Genisys is a very complicated movie, perhaps more so than any other in the franchise, and more than anything, it’s largely due to the direction they chose to take with this new entry.

The story begins in the now not too distant future of 2027 (back in the 1984 original, this would have been seen as a far off future date). The world is a wasteland now ruled by a race of robots controlled by the omnipresent artificial intelligence system known as Skynet. Only a small band of human resistance remains to take down the cybernetic overlords, and they are rallied together by their leader John Connor (Jason Clarke). Upon entering a key Skynet facility, they uncover the robot army’s secret weapon, a time machine. They learn that one of the robots, a Terminator, has already gone through the machine and was sent back to the past, setting up the events of the first movie. John Connor makes plans to use Skynet’s own weapon against it, and send one of his own men into the past to stop the Terminator from killing his mom, Sarah Connor (Emilia Clarke) before he is born. Kyle Reese (Jai Courtney) volunteers for the job and is sent back to the past, only to find that things are not what John Connor said they would be. Instead of saving a helpless and unaware Sarah, she ends up saving him with the help of her own guardian Terminator whom she affectionately refers to as Pops (Schwarzenegger). Kyle soon learns that the timeline that he’s from has been altered and that Skynet has begun a whole new strategy to ensure it’s survival; a Trojan horse operating system known as Genisys. In order to stop Genisys from going online, Sarah and Kyle travel into the future year of 2017 in order to prevent it’s launch, and they soon learn that Skynet has sent an unexpected guardian to the past as well to prevent them foiling it’s plan; John Connor, modified into a terminator.

This is a plot twist that could have been a shocker, had the studio not spoiled it in the trailers. But, it’s only one of the many twists and turns that this movie takes throughout the course of it’s running time, and that’s largely the biggest problem with the movie. This is a very plot heavy film, where many scenes are devoted to just explaining everything. But, by doing this, the movie removes any suspense that’s needed to be built up. It’s as if the filmmakers didn’t trust the audience’s ability to comprehend the finer details of the story, so it has everything spoon fed to us. Pretty much the entirety of the movie’s plot is as follows: action scene followed by exposition followed by another action scene followed by even more exposition; explosions and talking, repeat until the end credits. That’s about it. There’s nothing remarkable about the story here; it’s just more of the same from beginning to end, which is a far cry from where the series started. The 1984 original was a masterwork of suspense that didn’t need to detail everything about the universe that these characters exist in; in the end it was just a thrilling cat and mouse chase that was elevated by fantastic characterizations. Terminator 2 went into a more action oriented mode of storytelling, but the action scenes were so big and creative, that it didn’t matter how complicated the plot was. Terminator: Genisys is more or less just another routine action film, and one that relies heavily on your knowledge of the other movies in the series. As a result, it lacks identity, which is something that has characterized all the Terminator movies made without it’s original creator, James Cameron. The only defining thing about this movie is it’s attempts to update the technological reality of the Terminator world based on what we know today. There’s a statement made in here about the over reliance with integrated media in our lives, but it gets lost pretty easily in this convoluted plot. Basically Skynet has become an evil version of the Cloud system here.

There’s also a significant lack of vision in this movie. Visually, the movie is as basic and dull as an action movie can get. There’s no mood established, no trick photography; really nothing at all that we haven’t seen before in about a hundred other action movies. And, I hate to keep bringing up the other films in the franchise, but it’s a comparison that has to be made, because vision is one of the things that once defined the franchise back in the day. Before James Cameron brought the sinking of the Titanic to cinematic life and took us to the far off world of Pandora, his name was undeniably linked to the Terminator series. He redefined the sci-fi genre with 1984’s The Terminator with groundbreaking special effects and a unique take on the concept of time-travel; something that even astrophysics scholars have written papers on in response. The sequel took all of Cameron’s concepts and made them even more epic, establishing this franchise as not only a masterful work of science fiction, but one of the most defining ones of all time. Terminator 2 also broke new ground in the visual effects field, pioneering a lot of new technologies in CGI, which brought the amazing liquid metal T-1000 to life. Since then, Terminator has stopped being the leader of the pack and has just gone through the paces instead, particularly in the visual department. Genisys is directed by Alan Taylor (Thor: The Dark World), who takes a workmanlike approach to the movie that’s not bad, but not anything spectacular either. He’s basically just standing on the shoulders of what’s been done before. And what’s particularly troubling about the safe approach here is how unremarkable the visual effects are now. Really, the original Cameron-directed classics hold up much better as showcases for CGI than this more modern film does, because Cameron knew how to uses his effects for maximum impact. Here, it’s just an overload of CGI that altogether looks the same from scene to scene.

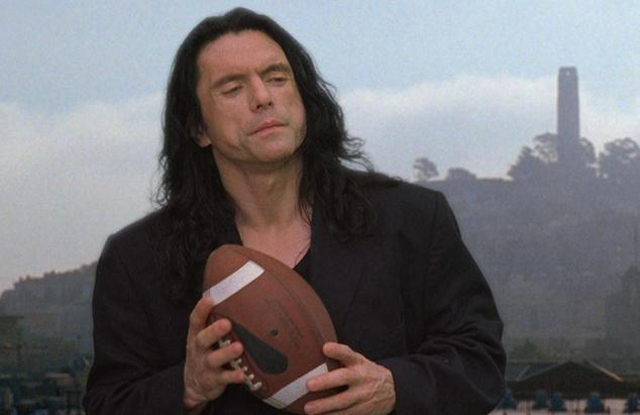

But, not everything in the movie is a disaster. There is one saving grace in the film and that’s the presence of Arnold. Let’s face it, these movies would not exist without Mr. Schwarzenegger’s star power and remarkably he’s still able to leave a much welcomed impression in this series. It’s not a remarkable performance per say, but Arnold does provide much needed levity in this movie with some hilariously delivered one-liners throughout. And it shouldn’t be surprising how comfortable he feels in this role either. It’s the part that made him a star, and he slips back into it here comfortably like an old pair of pants. Honestly, if the whole movie had just followed his lead, it would have been much more enjoyable to watch, but sadly he’s the one bright spot in a muddled mess. Even still, he’s a welcome element that helps improve the film significantly. I was smiling every time he was on screen, partly because of the nostalgia factor but also because Schwarzenegger still has unmatched charisma as a action movie star. If you take anything away from this movie, it will be any moment that he’s in. There’s a nice running gag throughout the film with Arnold’s Terminator making attempts to blend in, which results in an awkward forced smile (best seen when he’s getting his mugshot taken). There’s also another good moment when he and Kyle Reese get into a friendly competition as they try to outpace each other while loading their weapons. It’s little things like this that help make Arnold’s presence here worthwhile and he easily becomes the beating heart of this movie as a whole.

Sadly the remainder of the cast is a lot less consistent. Emilia Clarke is feisty enough as Sarah Connor, but her performance retains none of the resonance that she shows weekly in her role as Daenerys Targaryen on Game of Thrones. Her Sarah Connor is much more of a passive force this time around in the story, sidelined to basically reacting to the events rather than taking matters into her own hands, which is what Linda Hamilton’s version of the character did so well before. But I think that it’s less to do with how hard she performs and more so to do with the limitations put on her character in the script. Clarke does the best with what she’s given and thankfully she does a passable job embodying the now iconic heroine. (Interesting side note, Emilia Clarke now shares the role with one of her Thrones co-stars, Lena Headey, who played Sarah on TV in the Sarah Connor Chronicles series). The weakest cast members, however, unfortunately would be the two Australian stars, Jason Clarke and Jai Courtney. Courtney especially has been plagued by lackluster roles in action movies over the course of his career, although he is better served here than in the terrible A Good Day to Die Hard (2013). His Kyle Reese is serviceable, but pales in comparison to Michael Biehn’s standout performance in the original. Also, there is zero chemistry between the two leads here, which is something that defined the first Terminator so memorably. Jason Clarke also gets the enviable role of John Connor, and does very little with it. It’s a sadly passionless performance that displays none of the charisma that John is supposed to represent. It makes you long for the likes of Christian Bale, who himself had a hard time with the role. Hell, I would even prefer the ranting Christian Bale from the set of Terminator Salvation. The movie also brings in quality actors like J.K. Simmons and Doctor Who’s Matt Smith and wastes their abilities on underdeveloped roles. In the end, the movie makes a talented cast work hard for not much of a result, which is another disappointing aspect of this film.

So, how bad is this movie overall? I wouldn’t go as far as to say it’s the worst action movie that I’ve ever seen. Hell, it isn’t even the worst action movie of this year, or this summer. It’s just kind of a “Meh” movie from beginning to end; unremarkable in every way possible. Well, to be fair, any moment with Arnold Schwarzenegger is worth seeing, but there’s not much else of note to say about it. The action scenes are bland, the CGI is horrendously overused and generic, and the characters are just pale imitations of what they once were in better movies. As a standalone action flick, I guess it could serve it’s purpose, but unfortunately for Terminator: Genisys, it’s carrying the legacy of a once dominant franchise. And instead of expanding on the universe, this movie instead chooses to just cover old ground and tell us a story that we already know, adding nothing to the mythos. The vision that James Cameron created with his original movies is something worth exploring further, especially with all the new advances in technology that we’ve made in the years since; yet that’s not what we’re getting in the franchise today. But, even still, this movie isn’t so bad that it casts a dark shadow on the series as a whole. In the end, the first two Terminators still retain their classic status, and this new version is more or less on par with the last couple movies from the series. Having Arnold back certainly helps. Overall, it’s just a sub-par entry into a franchise that has seen better days and should probably be put to rest soon, or at least re-freshened with new ideas. As a diversion for this year’s Fourth of July weekend, I would recommend sticking with the fireworks, because you will find none with this Terminator.

Rating: 5.5/10