A few years back, in the early days of this site, I took a visit to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (aka LACMA) where they were holding an exhibition of the art and artifacts from the various movies of Stanley Kubrick; an interesting exhibit in it’s own that you can read about in my previous report here. Keeping in that tradition, the LACMA museum complex frequently holds special exhibitions like the Kubrick one to spotlight the great contributions filmmakers have made to the artistic world in general. In particular, certain visually driven filmmakers or special artistic movements in the history of cinema are featured. This year, LACMA’s selected person of interest is renowned Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro, whose body of work and visual style feels quite at home in the company of the museum’s extensive collection of artistic wonders. Del Toro has made a career out of delivering captivating visual treats; mostly within the world of the macabre and the weird. His films are vivid representations of a fertile creative mind and it’s great to see such an exhibit assembled to illustrate the cinematic imprint that he has left on the industry. Unlike the Kubrick exhibition however, this exhibit was produced conjointly with the filmmaker himself, with many of Del Toro’s own personal assets and collections making up a good portion of the exhibit’s artifacts on view. And also different from the Kubrick exhibit is the way that it is laid out. Whereas the previous gallery was set up to take us across the progression of a director’s career, film by film, the Del Toro exhibit is built more around themes and motifs; ones that have inspired the director’s creative process over the years.

Inspiration is at the heart of this gallery, as much of the sights on view showcase the process in which ideas are born from experiencing the works of art from a wide spectrum of sources, and how they’ve manifested in Del Toro’s own work. As stated in the gallery’s pamphlet and on the various plaques throughout, the exhibition is based off of Guillermo del Toro’s own privately owned gallery, where he houses all of his favorite collections of art and artifacts that he’s accumulated over the years. Apparently it’s a second home that he bought just for the purpose of housing all of his stuff, when his own living space became too crowded, and he has given it the special title of “Bleak House,” named after the famous Charles Dickens’ novel. This exhibition is clearly modeled after his private museum, and it’s great to see both Del Toro and LACMA collaborating together to give us a little taste of what it’s like to visit this private den of his and see where he draws his inspirations from. The gallery takes the home interior motif, and allows the different themes of Del Toro’s films to occupy each of the proceeding rooms, each displaying some of the artifacts on loan from Bleak House, as well as props from his movies, original artwork, and various pieces from LACMA’s collection that fit within the exhibit’s theme. I visited the gallery this weekend to give a thorough report of what I saw, complete with pictures. And like previous exhibitions on display at this immense museum complex, it’s an experience well worth exploring.

Upon entering the front facade on the ground floor of the Art of the Americas Building, you are greeted by the first of what will be many wax figure recreations of different characters from Del Toro’s films. This “beauty” that you see above is the Angel of Death character from Hellboy II: The Golden Army (2008), played by frequently used Del Toro actor Doug Jones. Of course, the grotesque but stunning sight gives you the perfect introduction for what else you will be seeing in the rest of the gallery; a mixture of the beautiful and the disturbing. Beyond this imposing figure is the first room of the gallery. Here you can see the visual motif of a home interior clearly visible, as the different walls lining the gallery are topped off with rafters, rising above each hallway, but with no roof to hold up on top. The first room’s theme is “Childhood and Innocence,” which is a theme that Del Toro explores in many of his movie, particularly with regards to the loss of both. Standing center in the room is the second wax figure, this time depicting the character Fauno from Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), also played by Doug Jones.

The “Childhood and Innocence” room also documents the years of Guillermo’s upbringing in Guadalajara, Mexico. On the walls, you will find a few childhood pictures on display as well as artwork from many of the different influences that shaped his imagination early on. Folklore and fairy tales were a big influence on him and none more so than Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. A copy of the book is displayed here, opened up to one of the illustrations that clearly left an impression on young Guillermo. Other works of art displayed include the works of Edward Gorey and Kay Nielsen, both artists who melded darkness and joy very well in their work, which was something that clearly appealed to Del Toro.

The next room takes us into one of the more obvious visual motifs found in Del Toro’s body of work, and that’s the influence of the Victorian era aesthetic. Dubbed “Victoriana” this room shows how the period style manifests itself visually within his many films, either overtly or subtlely. Of course, his most recent film Crimson Peak (2015) is spotlighted here, with authentic props and costumes from the film being displayed. Front and center is a collection of dresses, worn by Jessica Chastain and Mia Wasikowska in the movie. Across from them, you find a mixture of different influences that came from the Victorian period that inspired many of Del Toro’s different films. He often cites Charles Dickens as an inspiration, given the author’s sense of detail for the era, as well as his fascination with the dark and macabre in many of his stories. Del Toro borrowed the name “Bleak House” for this reason. You’ll also see how modernizing this aesthetic in the “steam punk” style also finds it’s way into Del Toro’s films, particularly in Hellboy (2004), and there’s a neat looking parody of a Victorian portrait featuring the comic book character in this room. My favorite artifact though is the painting of Madame Sharpe from Crimson Peak, a great prop that illustrates perfectly the fine line that Del Toro walks between the sinister and the silly.

Adjacent to the “Victoriana” room is a small section dedicated to Del Toro’s other favorite visual motif; Bugs. Insects find their way into almost every Del Toro film, whether they are the small creepy kind like those seen in Pan’s Labyrinth, or the large monstrous kind seen in films like Mimic (1997), or even the alien kind seen in Pacific Rim (2013). A cabinet displaying different kinds of bug life research is shown here, as well as different visual treatments drawn during the development of Del Toro’s movies. Accompanying these is another costume display; this one of the Ghost of Edith’s Mother from Crimson Peak, a creepy looking dress that carries over the insect motif, as you’ll see moths sewn into the fabric of the dress.

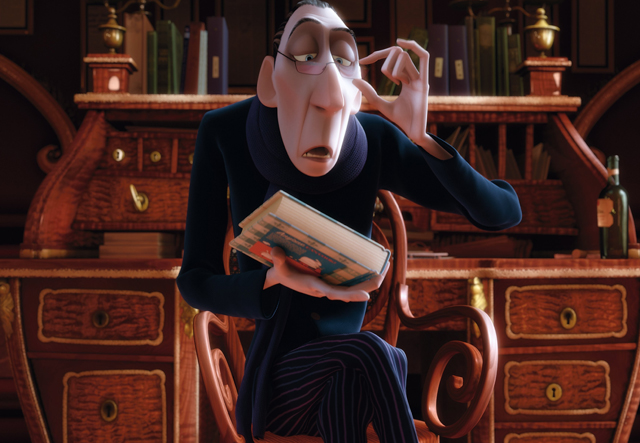

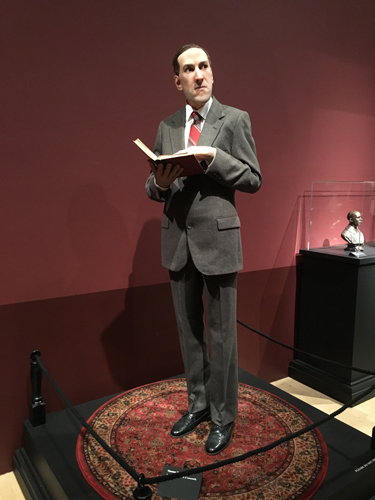

The next room covers the theme, “Magic, Alchemy, and the Occult.” Here, different influences from many different genres are spotlighted, mainly to show Del Toro’s fascination with the world of the paranormal. You see a mixture of magic and science mixed in here as well, as mechanical gadgets such as automatons are mixed in with magical artifacts like crystal balls and tarot cards. A giant wooden hand that was used on the set of Hellboy II is prominent here, as is a wax figure of one of Del Toro’s primary influences: H.P. Lovecraft. Many of the figures throughout the gallery were crafted by artist Thomas Kuebler, and his Lovecraft figure may be the most striking in the gallery. It’s so lifelike that I almost thought it was a real person standing there at times. Lovecraft, one of the most influential horror and sci-fi writers of the last century is a favorite of Del Toro’s, and he has stated many times that he intends on adapting the author’s classic At the Mountains of Madness into a film one day. Also included here is a nod to another of Del Toro’s dream projects; a painting of Medusa found in the Disneyland attraction “Haunted Mansion.” It’s interesting to see the influence of Lovecraft and Disney mingled together in this room, and yet both are true to the theme of magic that has clearly been a big part of Del Toro’s creative process.

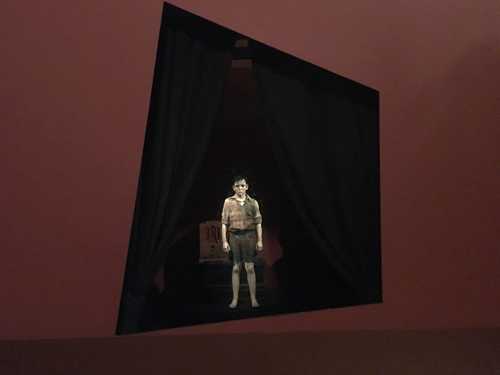

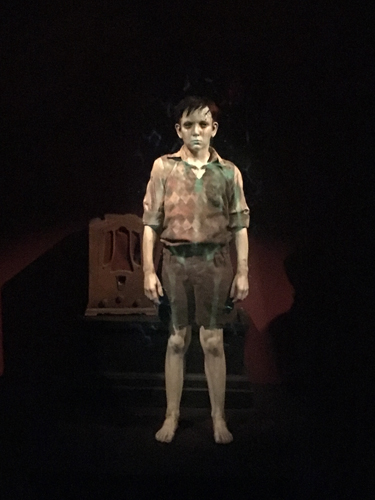

As you make your way down a lengthy hall to the next room, you see a wall cut out with a ghostly figure staring back at you through it. It’s another wax figure of one of Del Toro’s creations. This time, it is the ghost boy Santi from the film The Devil’s Backbone (2001). As you approach the display, there is a nice effect to replicate the way that the character looked in the movie, with transparent skin and a ghostly flow of blood blowing out of his head. This is done with the same effect that is used to create the ghosts at the Haunted Mansion, and it’s a nice little spectacle in this gallery. Perhaps more than anything else in the exhibit, this was the display that was being photographed by the most people. And like the Lovecraft figure, I’m impressed with the level of creativity and detail that was put into this attraction.

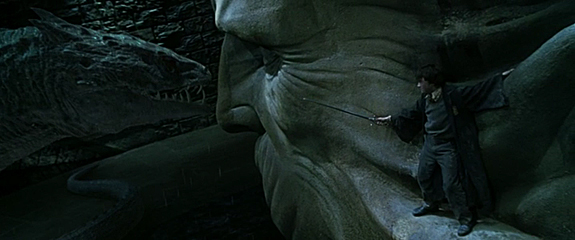

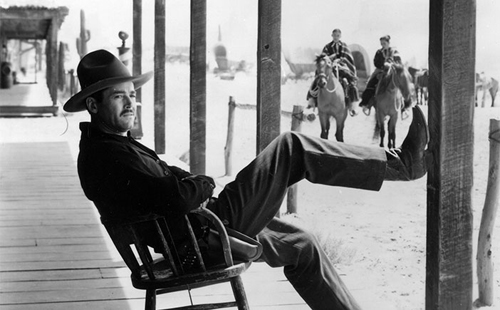

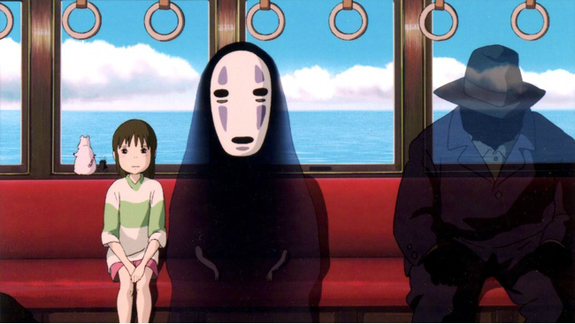

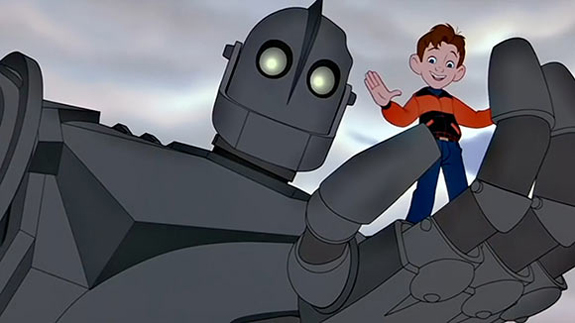

Into the next room, we see another huge influence in Guillermo del Toro’s life, and that is Pop Culture, particularly with Comic Books and Movies. Titled “Movies, Comics, Pop Culture,” this room presents many examples of the different comic books that Del Toro read during his childhood and up through his film career. The pamphlet states that Del Toro arguably had amassed the largest comic book collection in all of Mexico growing up, and whether or not that’s true, it’s undisputed that his films reflect a sense of love for the medium. Naturally, Hellboy is spotlighted here, with some of the props from the film on display, including the jacket for the main character, worn by actor Ron Pearlman. On the wall are various panels of comic book art from some of Del Toro’s favorites, as well as artwork from Mike Mignola, the creator of the Hellboy character. At the opposite end, there are tributes to two of Del Toro’s most beloved icons in the film industry; stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen and make-up artist Dick Smith. Harryhausen is represented by another lifelike figure, reclined in a chair, surrounded by some of his skeleton puppets from the movie Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Across from this is a larger than life bust of Dick Smith, the man behind the amazing make-up work on films like The Exorcist (1973).

Adjacent to this room is a small little section made to look like a 60’s era living room. Here, you’ll find more comic book artwork from around the world, including European artist Moebius. In the center is a pair of recliners and a table, facing a screen that’s playing a parody of a Mexican horror movie called The White Angel. It’s a short film that Del Toro made himself for the TV series The Strain, mocking the old horror B-Movies from Mexico that he himself probably grew up with, with a luchadore wrestler fighting off a cult of vampires. It’s the perfect kind of cheesy, which Del Toro likes to indulge in occasionally in his movies.

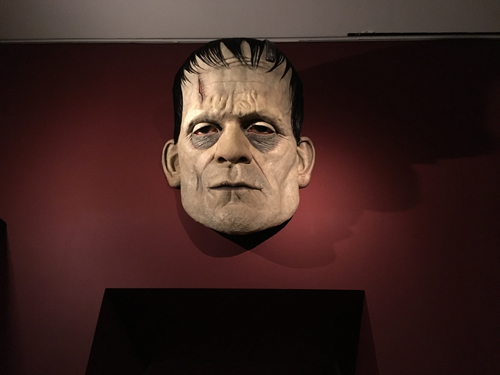

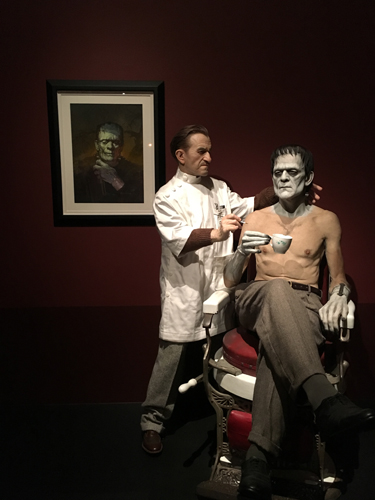

The next room’s theme is fairly obvious, as it celebrates the most singular of cinematic influences for Guillermo del Toro; Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Titled “Frankenstein and Horror,” the section not only celebrates the titular monster, but the overall visceral effect of brutality that Del Toro finds interest with, in the horror genre. You enter the section passing under a massive recreation of the monster’s head (one of the actual artifacts on loan from Bleak House), and you see numerous visual representations dedicated to the legendary novel and the classic film that was inspired by it. The highlights of this particular section are a couple of wax figure tableaus devoted to Frankenstein. The first one shows actor Boris Karloff in the process of having his make-up applied, showing the casualness of the performer before he must transform himself into a monster. The next tableau depicts a domestic setting, with Frankenstein and his Bride attempting to be intimate, while a menacing looking Dr. Pretorius looks on. Even as still figures, you get a nice sense of storytelling going on in these tableaus, and they make a welcome addition to the gallery. Also in this section, you see a cabinet full of macabre, cadaverous artifacts, including specimens in jars, skulls and books on the occult. Just like previous rooms showed the mystical and magical side to Del Toro’s work, this room begins to show the darker, more violent side of his movies; ones where he fully delves into some brutal imagery and themes. And it only gets weirder from there.

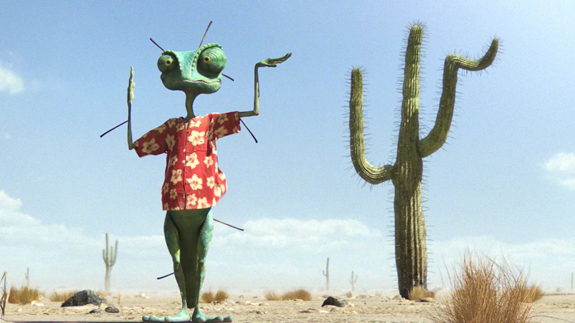

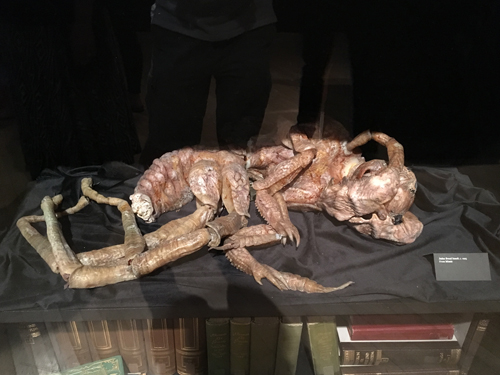

The next room is entitled “Freaks and Monsters” which carries over the fascination of the grotesque from the previous room. Here, the gallery spotlights the many creatures and abnormal human beings that inhabit the worlds of Del Toro’s stories. In the center, you’ll find wax figures of characters from another one of Del Toro’s favorite films; Todd Browning’s Freaks (1930). The film centers around a group of circus sideshow performers, and featured people with real physical abnormalities. But, what I’m sure Del Toro found fascinating about that movie was how each of the so-called “freaks” found strength and identity through their physical handicaps and were able to overcome prejudice from all the “normal” people out there. It’s that embracing of your peculiarities that Del Toro likes to explore in his movies and it’s why the movie Freaks is focused on here. The same film’s dark atmosphere and macabre sense of humor is also an influence that affected Del Toro, and you see a focus on how monsters and “freaks” are represented in his movies. Small figures of the Kaiju in Pacific Rim are found here, as is a replica of one of the Mimic creatures.

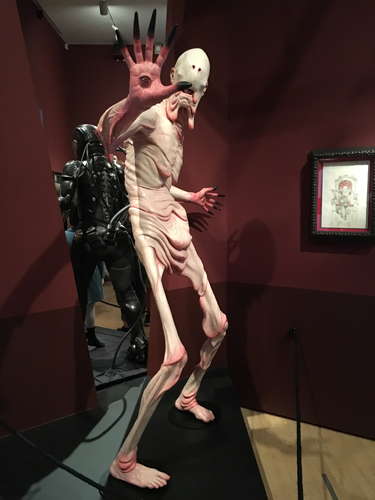

The final theme room is titled “Death and the Afterlife,” and it should be obvious what is focused on here. Ghost stories have long been a favorite genre for Del Toro to work in, as evidenced with The Devil’s Backbone and Crimson Peak, but it’s also the fear of death that characterizes many of his ghostly tales. Here, the specter of death is prominent, with representations of demons and vampires shown vividly around the room. A cabinet in the center includes nods to F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) as well as Francis Ford Coppola’s version of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). Also at the corner of the room is a vivid figure recreation of the Pale Man from Pan’s Labyrinth, one of Del Toro’s most frightening creations ever in any of his movies. I found it really interesting that this room is situated right next door to the room dedicated to childhood, seeing as how these two themes of Innocence and Death seem to combine very frequently in Del Toro’s movies. I don’t know if that was by design, but it definitely fits the narrative for this gallery. And it’s also fitting that situated right behind the Pale Man are costumes for the character of Mako Mori from Pacific Rim, a character whose whole drive in life was born out of the death of her family. Death and Rebirth, side by side. That spells out the gallery as a whole as the exhibit comes full circle.

But, passing by this finale to the tour, guests will notice a passage leading down to the middle of the gallery, hidden from all the other exhibits. You pass walls showing artwork from all of Del Toro’s favorite influences, from Gorey to Disney, and even portraits of his literary icons like Lovecraft and Edgar Allen Poe, and you finally find yourself in the final room of the exhibit. It is called “Del Toro’s Rain Room,” and it’s based off of a real space that Guillermo had made for himself in Bleak House. In the real room, Del Toro had it manufactured to where the windows would be rear projected to look like rain is falling from outside at all times, enhanced by little silicone droplets hanging down the glass plane and thunder sound effects playing in accompaniment. It’s a nice effect to make it look like a real rainstorm is going on outside, which I’m sure is the atmosphere that helps Guillermo find inspiration whenever he’s working in this room. Situated in the middle of this recreated space is the final wax figure of the gallery, one of Edgar Allen Poe, looking as content as he could be reclined in a chair in this macabre room. It’s a nice little added surprise, and I love the atmosphere that it emulates, especially with the digitally projected clouds on the ceiling.

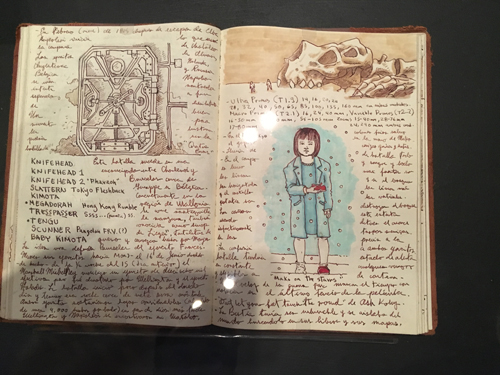

I should also point out that in addition to all the different artifacts that the exhibit has from Guillermo del Toro’s different films, as well as from Bleak House, the gallery also makes use of actual pages from the director’s personal notebook. The notebook in question is a documentation of all the ideas he has put down when he’s been developing his movies. Written in a mix of Spanish and English, it’s a neat little insight into the mind of a filmmaker. Even more interesting are the little sketches that he’s drawn within on some of the pages, showing the first ever visualizations of some of characters and creatures that would inhabit his movies. Various pages are found throughout the gallery, pertaining to that room’s theme, and in addition, there are touchscreen tablets that allow you to flip through scans of the entire book as a whole. I especially liked seeing what were ultimately the first ever drawings made of things like the Elemental in Hellboy II, or Young Mako from Pacific Rim, or of the entrance to the Labyrinth in Pan’s Labyrinth. Del Toro’s creative genius is found in that notebook and it’s a great little treat for him to share such a thing in this gallery.

So, there you go. I loved this exhibition and would recommend it to anyone, even if you’re not a fan of Guillermo del Toro’s movies. I understand that his style is not for everyone, but when you see such a well laid out presentation like this, even his detractors will find something fascinating to find. It’s not just a great presentation of one filmmakers body of work, but an examination of the processes that make a filmmaker who they are. It’s about the influences that shape an individual and gives them a voice. Here, you’ll find different kinds of art mingled together and how they came to influence certain films. It’s as much about the history of art as it is about the history of a filmmaker. You could create an exhibition like this for many other filmmakers, but Del Toro makes the ideal subject because the confluence of all these influences have yielded such an interesting result in his body of work. And as a movie fan, I just enjoy seeing cinema celebrated alongside other works of art on display in a museum. Guillermo del Toro’s exhibition is a worthy addition to LACMA’s long history of standout presentations and I would recommend it to anyone living in the Los Angeles area, or to those just passing through. The exhibit runs until November 27, so there is still plenty of time to view it. For a film buff like me, this was definitely worth seeing, and I’m happy to have shared it with you.

http://www.lacma.org/guillermo-del-toro/about-the-exhibition