Arrakis. Dune. Desert Planet. Ever since it’s original publication in 1965, Frank Herbert’s seminal Sci-Fi epic Dune has been a siren call to filmmakers wanting to bring the author’s vision to full cinematic life. Despite having all the grandeur in scope of a great biblical sized adventure, Herbert’s novel was also a dense and detailed tome, where worldbuilding is intricately to the story itself, something that would take a lot more time to adapt than what’s allowed for the average film. This led the book Dune to develop a reputation over time as being “un-filmable.” That’s not to say that there weren’t people who tried. One of the most famous failed attempts was from advant garde director Alejandro Jodorowsky (The Holy Mountain) whose early development of his vision of the movie was so wild and fascinating that a documentary was made about it called Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013). In that documentary, you see what may have been the greatest movie never made, as Jodorowsky details his bold vision for a space opera based on the novel that would rival the likes of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Of course, it was a dream un-fulfilled, and that’s a narrative that has long followed the history of Dune on film. Dune did eventually get a big screen adaptation by, of all people, David Lynch, who definitely leaned far more into the weirder aspects of Herbert’s novel. I talked about that adaptation more at length here, but to sum up, it’s a movie that leaves much to be deserved, especially if you’ve read the book. Lynch’s Dune (1984) for one thing rushes through most of the novel, and never allows for the worldbuilding to take hold. In the end it feels more like a Lynch movie than anything else, with only the bullet points of Herbert’s story. When Universal tried to add more backstory to make it more understandable to casual audiences, it angered David so much that he refused to attach his name to the longer cut, making it the most expensive Alan Smithee movie ever made. For decades afterwards, Lynch’s bizarre and compromised adaptation did garner a cult following, but long time fans of the novel continued to hope for a big screen adaptation that finally lived up to what was on the page.

After being passed around from studio to studio, the rights to Frank Herbert’s Dune eventually landed at Legendary Pictures, under their partnership with Warner Brothers. After securing the rights, the search went out for a director who was not only capable of delivering on the promise of Frank Herbert’s vision, but one who was also passionate about the project as well. The duty of such a daunting challenge eventually went to French Canadian filmmaker Denis Villeneuve. Villeneuve had already made a name for himself with critically acclaimed dramas like Prisoners (2013) and Sicario (2015), but more recently he’s been known for his celebrated work in Science Fiction, with movies like Arrival (2016) and Blade Runner 2049 (2017). The match was ideal for the up and coming director, as this has long been a dream project of his, ever since he read the novel back when he was a teenager. Once Villeneuve was given the greenlight, work began on bringing his long gestating vision to full life. Warner Brothers granted him a sizable amount to work with, including having an all-star cast playing all the iconic characters. Warner Brothers were hoping this would be the start of a new lucrative franchise for them, and the film was set up with a prime Holiday 2020 release. Then, unfortunately, the bad fortunes that seem to follow this story around, came to disrupt those plans. The Covid-19 pandemic made it impossible for Dune to make it’s original release date like all the other films that year, and Warner Brothers made the tough decision to push the movie back to 2021. As the pandemic waned, Dune settled into it’s new October release date, but another controversial decision followed with it. Warner Brothers decided they were going to release their entire 2021 slate of movies day and date in theaters and on streaming through HBO Max, including Dune. This led to friction with Denis Villeneuve who intended his film to be seen on the big screen. With this release pattern, many like Villeneuve worry that it will minimize box office and hurt any chances of a continuation of the series in case the movie appears to be a flop. Regardless, Warner Brothers stuck by their plan, and Dune is indeed receiving a hybrid release this week. The only question is, does it finally live up to the promise of the novel and demand a big screen viewing, or was Warner right to hedge their bets.

Dune (2021) pretty much follows the novel down to the letter with it’s overall plot. It is many millennia into the future. The galaxy is ruled by the Imperium, a multi-planet galactic federation that is ruled by the Great Houses, overseen by the Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV. Two of the Great Houses, the Harkonnens and the Atreides, are sworn enemies of each other, but still swear the same allegiance to the Imperium. Upon the decree of the Emperor, House Atreides has been granted stewardship of the desert planet Arrakis, where the Spice Mélange is harvested. The spice is the most valuable substance in the galaxy, granting those who consume it enhanced mental and physical capabilities, as well as enabling the process of interstellar flight. The one who holds control over the production of the spice wields great power within the Imperium, which leads many to wonder why the Emperor is suddenly changing the stewardship of the planet from one house to another. Until now, the Harkonnen’s, led by the fearsome Baron (Stellan Skarsgard) and his nephew Rabban (Dave Bautista), had been ruling the planet and it’s native people, the Fremen, with a tyrannical iron grip. Now, the Atreides, a benevolent and well-loved Great House, are making the move to Arrakis. Duke Leto Atreides (Oscar Isaac) brings along with him is beloved Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) and their son Paul (Timothee Chalamet). Paul Atreides has garnered a lot of interest from a powerful collective of witches known as the Bene Gesserit, of whom Jessica has also belonged. She is teaching Paul some of her special abilities, which are forbidden for men to learn, which the Bene Gesserit leader, Reverend Mother Mohiam (Charlotte Rampling), believes could prove problematic for the Emporer. It is thought that Paul may be the prophesized Kwisatz Haderach, an all powerful Messiah like being that can transcend time and space. Indeed, Paul’s dreams reveal a bit of his possible future, as he continues to see a mystery girl named Chani (Zendaya) within them. Once at Arrakis, Duke Leto’s trusted men, Gurney Halleck (Josh Brolin), Duncan Idaho (Jason Momoa) and Thufir Hawat (Stephen McKinley Henderson) do their best to train young Paul for a harsh new world. But as Paul will see, Arrakis is a perilous place full of assassins acting on the Harkonnen’s orders, as well as home to the mighty Shai-hulud, the massive, mountain sized sand worms that scour across the planet.

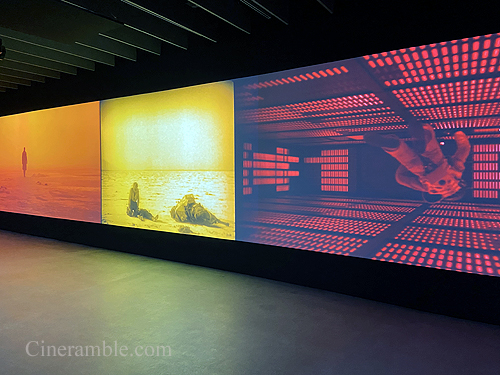

What I just described is basically just the set-up to the story of Dune and not the actual plot itself, which shows you just how dense of a story Frank Herbert’s narrative really is. It’s a daunting task to fit that kind of epic story into just one film, as David Lynch learned the hard way. With Denis Villeneuve, the task was to convince Warner Brothers that one movie alone was not possible to capture the full breadth of the story. His plan was to divide Dune into separate halves over the span of two movies. It’s not an unusual feat; several studios have split books up into two movies before, but they had the benefit of built in franchises like Harry Potter and The Hunger Games to allow for that. Denis was gambling with the studio here, but it’s what was necessary to carry out his full vision. Warner Brothers granted him his wish, but with a caveat; that he could only start off with the first half. Instead of filming back to back like other franchises have with multi-part movies before, Villeneuve had to do with filming only Part 1 of his adaptation of Dune, with the prospect of a Part 2 dependent on the performance of the first. That seemed like a fair compromise in a time of stable box office a couple years ago, but now seems short sighted in the wake of a global pandemic. Now, Denis Villeneuve’s chances of completing his vision are not so certain, as Warner Brother’s HBO Max gamble almost ensures that the movie is not going to perform up to it’s potential at the box office. And that overall is a real tragedy, because this is a movie that demands to be seen on the biggest possible screen. It has honestly been too long since I’ve seen a movie aim this high as a visual experience on the big screen, reaching for the heights of both the natural splendor of Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and the surreal head trip of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). This is the kind of epic movie that I absolutely love, one that pushes cinema to the limit, and Denis Villeneuve’s Dune is a masterful demonstration of that. I was blown away seeing this on a massive IMAX screen for the first time. Villeneuve, whose style is growing more and more ambitious with every new film, really holds nothing back in this movie. But, David Lynch also attempted an audacious cinematic experience with his version of Dune. What makes Villeneuve’s version vastly better is that he manages to solidify the tone throughout the movie, and treats it with the seriousness it deserves. And more importantly, he devotes more time to pacing the story out and letting it flow naturally.

Even when it’s only the first half of the book, Villeneuve’s Dune still runs at a meaty 2 1/2 hours. And a lot of that extra time gives us something that the David Lynch version never allowed before, a chance to immerse ourselves in this world that Frank Herbert envisioned. With the help of Cinematographer Greig Fraser, whose work includes films like Zero Dark Thirty (2012) and Rogue One (2016), Villeneuve creates an Arrakis that feels alive and tangible. I found myself in awe of the way that movie captures the vistas of it’s locations. Everything in this movie feels big, from the locations to even the machinery used by the characters. The ships that the Atreides use to transport themselves and their forces from planet to planet are colossal structures in of themselves, towering hundreds of feet and reducing the human beings among them to mere specks within the wide shots. And then there are the Sand Worms, which are probably the greatest creation of all from the mind of Frank Herbert. They are not seen much in this movie, but their presence is felt throughout, much like the shark from Jaws (1975). One of the most jaw-dropping visuals that I love from this movie is the way that we see the seas of sand dunes undulate as the Sand Worms move underneath. And then a massive sand pit begins to start sinking and entrapping anything or anyone unfortunate to be caught up within it. Around the center, hundreds of massive razor sharp teeth begin to rise up and engulf it’s prey, and then the gaping mouth of the beast closes in around it’s meal. It’s a terrifying sight taken right out off the page, and is a clear example of how well Villeneuve’s own vision perfectly matches Herbert’s. But apart from scale, I also admire how Denis also deals with simple, unspoken storytelling. There is a scene early on where Paul walks along a lake shoreline on his home planet of Caladan and places his hand in a puddle of water. Without words, he perfectly conveys the feeling of what is going through Paul’s mind at that moment. He’s doing something that is mundane on his planet that will become almost impossible on Arrakis, where water is so scarce that people have created suits designed to recycle the body’s own water. That’s a big, and valued change of approach for retelling this story. David Lynch was forced to cram in a lot of underlying backstory through awkward internal monologues. Here, Villeneuve says a lot more through visual storytelling, conveying emotion in his story rather than rigid adherence to a plot.

The movie also gets a lot out of it’s stellar cast, all of whom surprisingly fit well within this hyper-realized world. For one thing, Denis Villeneuve was wise to cast a youngish actor this time in the role of Paul Atreides. David Lynch’s Dune had Kyle McLauchlan in the pivotal role, but he was already in his mid-twenties when playing the part of the teenage protagonist, and he unfortunately looked it too. Timothee Chalamet is also on the latter side of 20, but he looks far more believably younger and you buy him as the character Paul much more. It’s a daunting part, no matter which way you look at it, because the role of Paul requires the actor to be in the mindset of being the so-called “Super” of the story; a sometimes overused cliché that has been used in many Sci-Fi and Fantasy stories, including many that Dune influenced. What I like about what Timothee brings to the part is the quiet pain that he feels as the character. You feel the world-weariness of the character, as he struggles with being at the center of all these political and supernatural machinations, all the while trying his best to be a normal, level-headed young kid. And thankfully, Timothee also accomplishes this without turning Paul into an angsty, whiny privileged teen, which could’ve happened in the wrong hands of a different actor. He’s also matched with an incredible performance by Rebecca Ferguson as Lady Jessica. She delivers so much emotion through her role, and it’s nice to see a maternal character treated like a powerful force within this adaptation. Oscar Isaac makes his Duke Leto a man worthy of admiration, and the supporting roles Gurney and Duncan are filled perfectly by the always reliable and charming Josh Brolin and Jason Momoa respectively. There’s one underwhelming part of the cast in the movie and that’s the villainous Harkonnens themselves. Stellan Skarsgard and Dave Bautista are still excellent in their performances, but the movie doesn’t really utilize them to the fullest. They are just there, and fulfill their part in the story, with no real insight into their character motivations. It makes me wonder if Denis was saving that more for Part II, instead. In any sense, even with all the extra time, it seems like the villains were treated like an afterthought in this film, but they are still well acted and creepily designed. I do hope we are going to get more characterizations fleshed out in the future, but even still, the cast really delivers in their roles. Like all the best films with a stacked cast of knowable faces, the best sign of the movie’s effectiveness is in seeing how the actors start to disappear throughout the movie, and we instead only see the character they are playing. That’s the great trick that the Lord of the Rings movies pulled, and I’m glad to see that it works just as well here too.

There’s also a lot to say about the incredible aural experience that you’ll have watching this movie, especially in a theater retrofitted with a spectacular sound system. For one thing, Hans Zimmer’s score is up there with the legendary composer’s best work. With worldwide influences, Zimmer’s score gives an identity to the world of Arrakis, and captures through music the incredible wildness of that world. Equally adept at capturing the big action moments with the quieter reflective ones, Zimmer’s score has a beautiful fluidity to it that perfectly matches the visual splendor that Denis Villeneuve puts on display. The sound editing really utilizes the dynamic sound field very well. It’s this specifically this that you will only get to hear at it’s fullest potential within a movie theater. Home theater set-ups won’t rattle the ribcage and get the heart pumping like the sound systems of a multi-channel theater set-up can, especially one at an IMAX theater. The rolling thunder of the oncoming Sand Worms especially have a foreboding sound to them. There’s also a lot of brilliant work put into the art design of the movie and the special effects. The David Lynch movie had it’s weirdness to be sure, but there are a few places and sights in this movie that also delve into the strange and bizarre. I especially like the H.R. Geiger inspired look of the Harkonnen home world, which I think is a deliberate nod to Jodoworsky’s unfulfilled vision, as Alejandro did in fact commission Geiger to design the Baron’s palace for his movie, years before Geiger went on to famously design the iconic creature in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1978). If this was the case, I applaud Denis for acknowledging the legacy of Jodoworsky’s imaginative but never made version, which only lives on as a collection of development art. Another thing that I love about this movie is that it mixes practical and digital effects really well. Since Denis Villeneuve is like Christopher Nolan in that he tries to do as much as he can in camera before adding digital enhancement, I’m happy to see so much in this movie that looks authentic and real. The digital effects are subtly laid in, and there is quite a lot of use of physical miniature models to help make the mighty fortresses in this story feel real. In a Marvel and DC world that has become too accustomed to blue screen and CGI enhancement, it’s great to see a movie fall back on some tried and true old tricks to help make Arrakis and all the other worlds of Dune feel as real as possible.

Of all the movies to have released in this re-building year at the box office, this is the one that makes the most passionate case yet for returning to the movie theater. There really is no better way to appreciate the film and it’s massive scale. Unfortunately, because of Warner Brothers not backing down from their year long gamble on HBO Max, there is a chance that too many people will end up staying home and not get the full experience of this movie. I understand that it’s still too unsafe for some people to venture out as the pandemic still continues to exist and that streaming the movie at the same time it’s in theaters grants people who are not ready yet the chance to not miss out. But, Warner Brothers is putting too much on the line with this one. It’s foolish on their part to not consider having Denis Villeneuve shoot two movies back to back, so that even if the first movie underperforms, he’ll still have the second part to complete the story. Here, the movie ends on an abrupt note, making it far more dependent on a continuation to follow. If Warner Brothers doesn’t invest in a sequel right after this, it’s definitely going to come across as an incomplete vision. I guess that it would put the movie in line with other past Dune projects, like Jodoworsky’s unmade film or David Lynch’s compromise, as they both reached far and came up short. Frank Herbert’s masterpiece is a daunting challenge, but Denis Villeneuve’s visual feast is the best attempt yet at finally bringing the story to it’s full cinematic potential. Sadly, I think Warner Brothers is going to leave a lot of money on the table with regards to this one, all in the pursuit of pushing for more subscribers to their streaming channel. I hope that word of mouth helps this movie find it’s audience, and helps convince the WB team that they need to complete the full vision. It’s all going to come down to dollars and cents at this point, and it only makes it more complicated when you know that, like Arrakis, Warner is currently going through a leadership change of it’s own (from AT&T to Discovery) which could dampen Dune’s chances even more. All I can say is this was absolutely the best theatrical experience I have had thus far this year, and after the last year that we’ve had, it’s a feeling that I have long wished would return. Denis Villeneuve has done a masterful job of taming Frank Herbert’s “un-filmable” novel and giving us a movie worthy of it’s legacy. if you can, I cannot recommend more highly enough that you should see it in a theater on the biggest possible screen. It is the kind of movie that reminds us the power that cinema can have, and it does so with a world we have yet to fully see realized in a way that captures it’s true epic potential. The grandfather of all modern science fiction now finally has a movie worthy of it’s legacy. Now it’s up to us to help it become a hit so that it won’t remain an unfinished masterpiece. The spice must flow.

Rating: 9/10