If there was ever a reason to take the early months of the year seriously as part of the release calendar for Hollywood movies, this last year clearly showed it. Not only did the winter and spring months of 2018 provide the two highest grossing movies of the year (Black Panther and Avengers: Infinity War), but it also was instrumental for spring-boarding the entire box office for the year into record breaking numbers. Often viewed before as the dumping ground for movies too small or problematic to be considered tent-poles for major studios, the early quarter of the year now yields just as many blockbusters as it’s long-established brothers of Summer and Fall have over the years. In some ways, it’s now the fall season, once dominated by the likes of The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter, is now the part of the year that’s struggling to keep up. What’s most interesting about the early part of the year now is that it’s benefited greatly from strong performances by the horror movie genre. Last year saw incredible success from critically acclaimed thrillers like Hereditary and A Quiet Place, both of which performed much better than their summer and fall equivalents. This was also the case the year prior with Jordan Peele’s Oscar-winning Get Out (2016), which immediately stood out in the month of February where there was no other movie like it to compete. That’s probably why the early part of the year is being looked at as a great place to take chances and make movies shine in a box office period that is less crowded. Like last year, I will be looking at the most anticipated movies coming to theaters over the early part of this next year, including the ones that I believe are must sees, the ones that have me worried and the ones that I’m sure are worth skipping. Keep in mind, these are just my impressions based on my excitement level for each one and what I believe are their strength and weaknesses based on the effectiveness of their marketing. I’m not always right in this regard, and some of these could turn out to be surprises; good or bad. So, with that, let’s look at the films of early 2019.

MUST SEES:

AVENGERS: ENDGAME (APRIL 26)

Because of a last minute date change from last year, I couldn’t include Avengers: Infinity War in my early 2018 preview, even though it should have belonged there in the long run. Thankfully, Marvel opted to schedule it’s followup, Endgame, for the same end of April release which makes this a lot easier this year. Avengers: Endgame no doubt wants to make sure that it receives the same worldwide roll-out that Infinity War did, and with it, making sure all the plot secrets are revealed across the world at the same time. This was especially necessary for Infinity War, as it left audiences with the most talked about cliffhanger since The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Now, Endgame comes out a year later giving us a resolution to that story. Because of the shocking development at the end of the movie where (SPOILERS) Thanos (Josh Brolin) wipes out half of all life in the universe with the full power of the Infinity Stones, anticipation is high with audiences deeply interested in knowing what comes next. We know that what happened is likely to be reversed, but the question is the how? How is it all going to play out? The trailer leaves us with even more questions that will likely make this a harrowing story by itself. Why is Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.) alone in space? What happened to Hawkeye (Jeremy Renner) to make him go rogue? How did Ant-Man (Paul Rudd) get out of the quantum realm? Some argued that the movie didn’t need any marketing, because of how effective that cliffhanger was, but it’s a good sign when the trailer shows us just enough without spoiling what happens next. There is little doubt that this is going to be another gem in the Marvel Studios crown, the only question is how big of a boost will this one get after where Infinity War left us, and can it live up to that moment?

GLASS (JANUARY 18)

Speaking of super heroes, here we have a long awaited follow-up to one of the greatest deconstructions of the genre that’s ever been put on screen. M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable (2000) was a brilliant look at how the tropes of comic book characters and their stories could play out in a real world setting, and it delivered a plot twist by the end that rivaled even Shyamalan’s famous Sixth Sense finale. Unfortunately, Unbreakable couldn’t come out of it’s predecessor’s shadow, performing underwhelmingly at the box office, and after making Signs (2002), Shyamalan descended into a creative spiral where he was forced to try to replicate the Sixth Sense success again but failed time and time again, falling into self parody. Thankfully, he ended up partnering with Blumhouse Productions, and their mutually beneficial collaboration resulted in his first runaway hit in over a decade, with the surprisingly tense and effective Split (2017). What even amazed people more is that with a end credits cameo from Bruce Willis, we found out that Split was in fact a back door spin-off of Unbreakable and that Shyamalan was intending to do something that I’m sure he has long wanted to do but never could, which is to revisit this narrative once again. I picked Unbreakable as my favorite film of the year 2000, and it thrills me to not only see a continuation of this story, but to also feel excited for a Shyamalan movie once again. We are finally seeing him in his element again, with a story that best fits his style of film-making, and even better, he managed to assemble all the same players again. James McAvoy, who was amazing in Split, is joined by Unbreakable’s Willis and Samuel L. Jackson, whose villainous Mr. Glass gives the movie it’s title. I really hope that this one lives up to the legacy of both the movie and of Shyamalan’s best work, because Unbreakable is an underrated masterpiece, and I’m glad that it now has the sequel that it’s long deserved.

CAPTAIN MARVEL (MARCH 8)

As if we didn’t have enough super hero movies to be excited about, here is another from the unstoppable force that is Marvel Studios. Here, we get another groundbreaking effort from the team , which sees their first film ever to headline a female lead; that being the titular super being. Benefiting greatly from the star power of Oscar winner Brie Larson, Captain Marvel is a major addition to the Marvel roster who is sure to make a huge splash this spring at the box office. Seeing how well DC’s Wonder Woman performed with it’s own super heroine, this should be another example of the viability of a female driven action film that can compete just as effectively as those starring male super heroes. Also, given how important Captain Marvel is to the overall Marvel canon, it’s long overdue to see her join the roster and make an impact on the MCU in general. Especially given the mess that Thanos left the universe in, it’s going to be exciting to see her make her debut in the role of a savior; which is heavily hinted at in Infinity War’s post credits scene. This movie sets that confrontation up well by showing her backstory, as well as her place in the story overall; setting it in the 1990’s, where she encounters some familiar faces of the past. Chief among them is a still green SHIELD agent named Nick Fury (Samuel L. Jackson, again), and the movie not only looks to be an origin tale for her, but him as well. The movie also introduces us to the Skrulls, some of the most legendary bad guys from the comic books, and their shape-shifting powers could offer up some intriguing story possibilities not just for this film, but for all the Marvel movies both past and present. Captain Marvel on the big screen has been long overdue, and it’s exciting to see Marvel finally give her the spotlight she deserves.

THE LEGO MOVIE 2: THE SECOND PART (FEBRUARY 8)

When the first Lego Movie premiered in 2014, it was the surprise of the year. What could have easily slipped into a cheap cash in and a shameless commercial for the product it’s based on, Lego Movie instead proved to be a remarkably smart, funny, and even heartwarming animated treat. This was accomplished in no small part to the excellent work of writers and directors Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, two of the greatest humorists to have emerged in the last decade. Sadly they are not directing this sequel, but they did contribute to the screenplay, and the last time they contributed to a screenplay that was not their own film, it was the incredible Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse. Apart from the directorial change, everything else about this movie seems to be in tact. The cast returns, including Chris Pratt and Elizabeth Banks as the two leads, as well as Will Arnett in his scene-stealing role as Batman. Chris Pratt even gets to play two roles this time; his original character Emmitt, and a gritty newcomer named Rex Dangervest, which is an amalgam of all the other characters Pratt has played in other movies, like Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) and Jurassic World (2015). My hope is that the movie finds new and clever was to play around in this Lego world than it has before, and not just be a rehash of the original. There is strong precedent for the movie to work, as the spin-off Lego Batman Movie (2017) was also a delightful romp. It is hard to make a sequel to a movie that should have never have worked in the first place, because at this point the novelty is gone, and now people expect that it to be good. Given the people involved, I can see this matching it’s predecessor, and hopefully maybe even surpass it.

HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON: THE HIDDEN WORLD (FEBRUARY 22)

Dreamworks Animation has had a shaky couple of years, with box office numbers considerably lower than their hits of years past. Not only that, but the shifting around from studio to studio has also led to a downgrade in their once powerful brand. Now, it seems they have found a home with Universal Studios, and their first collaboration with their new distributor is a third installment from arguably their greatest series to date. The first How to Train Your Dragon (2010) was an instant classic when it first released, and is widely regarded by many (including myself) to be the high water mark for Dreamworks. The 2014 sequel even defied expectations, and was widely regarded as just as good as it’s predecessor; something most animated sequels rarely do. And even with the changing tides of the animation industry, How to Train Your Dragon is still seen as a valuable property. So, it makes sense that Dreamworks would once again revisit their beloved franchise, hopefully as a way to regain some of their lost mojo. The addition of a love interest for the film’s mascot dragon, Toothless, seems to be a smart way to add extra narrative spark to this story-line, and the courtship scenes shown in the trailer are wonderfully silly. Also, a dragon hunting villain voiced by F. Murray Abraham makes another exciting addition. Even with all the new elements, the touching relationship between Toothless and his human keeper Hiccup (Jay Baruchel) still remains at the heart of this trilogy, and it looks like it’s going to come to a touching and emotional end as this is likely the finale to their story. Let’s hope that Dreamworks sends this series out strong, as it has been the crown jewel of their studio so far.

MOVIES THE HAVE ME WORRIED:

DUMBO (MARCH 29)

You already know from my reviews that I have mixed feelings about Disney’s recent trend of remaking all their animated classics. Some are good (Cinderella, Pete’s Dragon) but most are bad (Beauty and the Beast, Maleficent), and this year we got three more. This summer will see remakes for Aladdin and The Lion King, but before them, we are getting a remake of one of the studios most legendary and beloved classics. Perhaps the trickiest of remakes to get right, the beloved Walt-era masterpiece Dumbo is getting it’s own update, and the one responsible for pulling it off is Tim Burton. Giving this project to the likes of Burton is a mixed bag. He is an incredible visual artist, and from the trailer, we can see that this is an exquisitely produced, visually interesting movie; playing well to his strengths. However, the last time he was tasked with updating a Disney classic, it was the unappealing Alice in Wonderland (2010). With Alice, Tim Burton made a movie that had all the visual excess that he is known for, but with none of the restraint or focus, and it resulted in a very disappointing experience overall. Dumbo is a more emotionally driven story, and one hopes that Tim Burton can find a more consistent tone that is faithful to the original, while still making good use of his visual style. On the plus side, the movie does team Burton up with Michael Keaton, who haven’t worked together since Batman Returns (1992), and I’m excited to see those two collaborating again. The trailer also gives off a Big Fish (2003) vibe, which is good considering that’s one of Burton’s more subtle and effective features. Let’s hope that he does the original justice, because if he doesn’t, this could be a movie that faces some severe fan backlash.

SHAZAM! (APRIL 5)

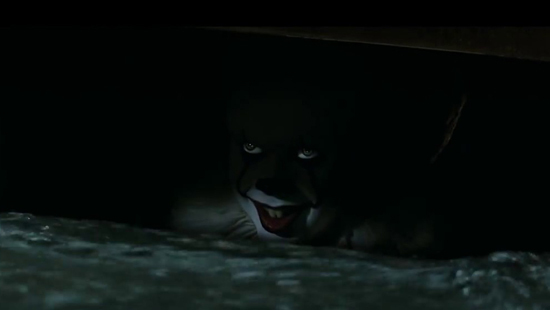

Another series that has a lot to prove is the DC Extended Universe. After many years of playing catch up to Marvel, DC has found a small bit of success lately with Wonder Woman and Aquaman. Now while I did enjoy Wonder Woman a great deal, Aquaman left me a bit underwhelmed, despite some moves in the right direction. But, in trying to catch Marvel, DC also runs the risk of over-correcting, and look like they are just playing copycat. That could be the downside of their next film, Shazam!, which brings to the screen one of DC’s more lighthearted, comical characters. After years of being criticized for it’s grim and dark tone, the DCEU is starting to lighten up, favoring a sense of humor and brighter colors that feel much more Marvel like that what they made before. This is where they run the risk of making too much of a heel turn. Shazam! looks like a comedy dressed up as a super hero story, with the Tom Hanks movie Big (1988) providing heavy inspiration, which could play well on it’s own. But remember, Marvel has many more years experience with these kinds of movies. Shazam! could end up being too silly to be taken seriously as a part of DC’s attempts to salvage their franchise. And given how Aquaman couldn’t overcome it’s own shortcomings even despite the attempts to change it’s tone as a part of the universe, makes me also doubt that Shazam! can do it too. The casting of Zachary Levi could work for the character though, since he has the build and the personality to pull the character off. I also like the chemistry between him and the best friend character, played by IT’s Jack Dylan Grazer. Hopefully this is more of a step in the right direction for DC, which even after some positive movements is something they still desperately need.

HELLBOY (APRIL 12)

Is it really too soon to reboot this franchise? I ask because the original duo of features directed by Guillermo del Toro still stand up pretty well even a decade later. I understand wanting to bring this franchise back, but the sad thing is that this looks like a complete do over with a new cast, director and story-line; throwing away all that the other films had already established. Couple that with the fact that it seems like only Hellboy himself made the transition over, as beloved sidekicks like Abe Sapian are left out this time. The movie has Stranger Things alum David Harbour taking on the role after original Hellboy Ron Pearlman. Harbour is a good choice to play the iconic hero, and this is his first lead role in a major studio film as an actor, which is a great development in his career; one in which the stalwart actor has justly earned. He has big shoes, or hoves, to fill as Ron Pearlman left such an iconic mark on the character, one in which he seemed destined to play. I hate to think that this movie is scrapping all the story and continuity of the Del Toro films to begin anew, so whatever they have planned for this franchise, let’s hope that it lives up to what we’ve seen thus far. It appears from the trailer that the new film maintains the same sense of humor, and I like the addition of Ian McShane in the mentor role that was previously filled by the late great John Hurt. And there are some interesting visuals on display in the trailer, which take their visual inspiration from Del Toro’s own unique style. I hope that it’s a revival worth celebrating, and not just a cash grab to capitalize on a property in the middle of this super hero era that we are currently experiencing.

ALITA: BATTLE ANGEL (FEBRUARY 14)

Some movies just take longer to become a reality than others; but eventually the longer they take, the less likely they are able to work as well as they were supposed to. Alita: Battle Angel has been a pet project of filmmaker James Cameron for nearly twenty years. Even while he was completely immersing himself in the world of Avatar (2009), he still had this one developing quietly in the background. Eventually, with the Avatar sequels taking up most of his time as a director, he was left with the reality of not being able to bring this movie to the screen himself, so the project was passed along to another, with Cameron overseeing as producer. Robert Rodriquez, an equally ambitious and experimental filmmaker when it comes to visual effects stepped in to finally bring the film to the big screen, but even with his help, the movie still faced numerous delays, and was pushed back several times on the release calendar. It’s now ready to make it’s way to the theaters this February and the only obstacle that remains in it’s way is; do people still care? There’s no doubt that this is going to be a visually stimulating movie, with the motion capture technology that James Cameron pioneered with Avatar being used to create a life like version of the titular heroine. Again, the technology used could be a blessing and a curse, because though the results are impressive, it runs the danger of falling into uncanny valley territory. The movie does have an impressive cast to help things along, including Oscar winners Christoph Waltz, Jennifer Connolly, and Mahershala Ali. Only time will tell if the wait was worth it for this one.

MOVIES TO SKIP:

CAPTIVE STATE (MARCH 29)

Every now and then we get these heavy handed political allegories that often loose control of the message once the narrative turns more convoluted and unfocused. Prime example was the disastrous Elysium (2013), which had some of the laziest, socially conscious sermonizing that I’ve ever seen put on film. It can be done well, like the brilliant Snowpiercer (2014) from Bong Joon-ho, but that one benefited from a grounded in reality concept that made the political subtext more palatable. Captive State however rehashes the same old alien invasion plot-line that’s become old hat as a commentary on modern society. The only variation that it offers is that this is a world where Earth has been long colonized by a tyrannical alien invader, which has imposed strict societal control on all earthlings. That’s the general take that I get from the trailer, and though it may be different in the final film, I can pretty much speculate exactly where the story is going to go. I have no problem watching a movie with a political allegory; even a movie such as this which goes against my own political beliefs, just as long as the story is still engaging. Sadly, Captive State looks like just another in a long line of wannabe grand statements that wants to reveal the world for what it really is, and yet still compromises itself to be a standard action thriller just like all the rest. I’m pretty sure there will be very few surprises with this one.

WONDER PARK (MARCH 15)

One of the things that especially defines an underwhelming animated feature is the way that some stretch a premise to the point of breaking. A light weight story always spells doom for bad animated films, and Wonder Park looks to fit that bill exactly. Here we find a young girl who builds model theme parks and rides as a hobby, but looses interest once she is hit with tragedy. Later she finds that her park has come magically to life and she must rebuild it in a metaphorical journey to also rebuild her own self-esteem. I can already tell where this story is going to go, and I already don’t like it. These coming of age stories are already old hat in animation, mainly because pretty much every studio has done it before. Also, as seen in the trailer, the movie relies too heavily on slapstick and innuendos, which is a clear sign of lazy writing for an animated film. I’m sure that it may end up looking pretty, but again, this is a medium where Disney, Pixar and Dreamworks have pushed the medium to new heights. Wonder Park just has this sub-par feel to it, like one of those films you would see from an upstart studio trying way to fit in with the big guys.

A DOG’S WAY HOME (JANUARY 10)

One of the most hilariously inept trailers that I have seen in a very long time, the above advertisement gives away pretty much the entire movie in it’s short 2 1/2 minutes. That’s not a good sign already that your story only offers little over two minutes to explain every plot point, even the ending. Basically a poor man’s Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey (1993), A Dog’s Way Home is another in this strange new shared universe franchise of talking dog movies. This one comes to us from the same people who made A Dog’s Purpose (2017) an equally lightweight and vacuous dog movie. This is exactly the kind of movie that you’d expect to be dumped off in the month of January, as it seems to only be marketed to a small segment of people who are avid dog lovers. And believe me, I love dogs too; it doesn’t change my belief that this is going to be a terrible movie just like it’s predecessor. At the very least I did get a laugh at the fact that the entire movie’s plot is given away by the trailer, indicating to me that the marketing team behind this film doesn’t care much for it either.

So, there you have my look at the upcoming winter and spring films of 2019. Just like years past, it looks like Marvel will once again dominate at the box office, and this could especially be a record breaker for them which says a lot. With the completion of the Avengers story-line with Endgame, plus the premiere of Captain Marvel, the mighty Marvel machine is not even close to slowing down. I’m also especially excited to see Shyamalan’s return to the genre after such a long hiatus with Glass. There could be a few surprises in there too, though most likely from movies that I left out of this preview. Independent movies, which seem to do well no matter what time of the year it is, will almost always be worth watching and the current slate of streaming films that are beginning to make a splash on platforms like Netflix and Amazon, with Disney+ and Apple just about to widen the playing field more in the coming year. What’s great is that blockbusters are no longer confined to certain parts of the year, but are in fact found in every month now. That was evident by Black Panther’s record breaking run this year in the month of February. Perhaps Hollywood is seeing now that these early months no longer need to act as a dumping ground for their trash, but fertile area to really make their movies shine with an uncrowded market. It’s something that we’ll likely see exploited more in the years to come, and I’m just happy to see movies worth getting excited about coming out sooner rather than later in the year ahead. So, let’s celebrate the New Year and have a good time at the movies in 2019.